History of Wood Island Lighthouse, Biddeford Pool, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

A most noble and exhilarating prospect of sea and shore presents itself at one glance. Here, at our left, comes the Saco from its mountain home; right before us, Wood Island lights the entrance, and Stage Island breaks off the seas that come rolling in toward the river's mouth from the broad Atlantic. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Wood Island, about 35 acres in size, lies about two miles east of the entrance to the Saco River and less than a mile from the village known as Biddeford Pool. Biddeford Pool gets its name from a tidal inlet known simply as “The Pool,” bounded by Fletcher’s Neck to the south and Hills Beach to the north.

The communities of Saco and Biddeford grew up on the banks of the Saco River, and around Winter Harbor at the river’s mouth. The first sawmill in the area was established in 1653, and textile mills grew into the chief local industry. Fish and lumber were the other major exports.

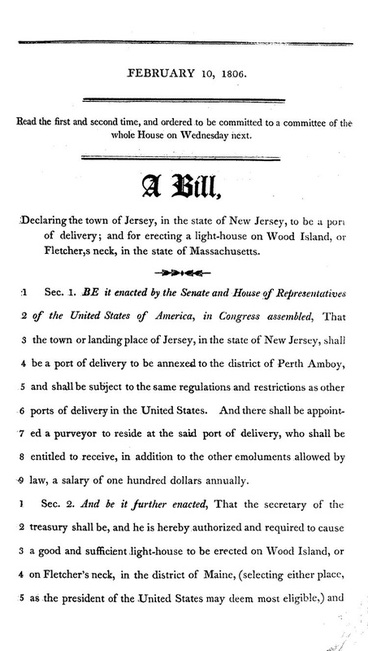

Fletcher’s Neck was considered a hazard to navigation, and Congress appropriated $5,000 for a lighthouse on Wood Island in March 1806. The government purchased land for the station from Pendleton Fletcher for $160.

The communities of Saco and Biddeford grew up on the banks of the Saco River, and around Winter Harbor at the river’s mouth. The first sawmill in the area was established in 1653, and textile mills grew into the chief local industry. Fish and lumber were the other major exports.

Fletcher’s Neck was considered a hazard to navigation, and Congress appropriated $5,000 for a lighthouse on Wood Island in March 1806. The government purchased land for the station from Pendleton Fletcher for $160.

The light station was completed by September 1, 1807, for a sum of $4,750. The builders, Benjamin Beal and Duncan Thaxter, were subcontractors for Winslow Lewis. For reasons that aren't clear, the 45-foot octagonal wooden lighthouse didn't go into service until the following year.

The first keeper, at a yearly salary of $225, was Benjamin Cole, who had been captain of a privateering vessel during the American Revolution. There were problems from the start. The local customs collector and lighthouse superintendent, John Chandler, called the wooden tower “rotten” in 1835 and complained that it “rocked” in rough weather.

The 1808 tower lasted until 1839, when a new 44-foot conical rubblestone tower—20 feet in diameter at the base and 10 feet at the top—was built, along with a new one-story granite dwelling, after a congressional appropriation of $5,000 in July 1838. The revolving light was 69 feet above mean high water. A rotating “eclipser” created the appearance of a flash at certain intervals.

The engineer I. W. P. Lewis, in his 1843 report to Congress, wrote that the base of the tower rested on an uneven ledge, the walls were cracked and leaky, the mortar was bad, and the woodwork was decayed. The one-and-one-half- story keeper’s house was also in a deplorable state; the windows were leaky, the cellar had no floor and was wet and muddy, and the entire building was “very defective in materials and workmanship,” according to Lewis.

In a letter in September 1842, John Anderson, superintendent of lighthouses in Maine, had defended the construction of the tower. “I am satisfied that the mortar used was made of good lime,” he wrote, “and sand was not wet with salt water. . . . I appointed an experienced and skillful stone mason of established good reputation.”

John Adams, who had become keeper in 1841 at a yearly salary of $350, provided a statement for Lewis’s report. He was provided a boat, but there was no landing place or shelter for it. Adams’s predecessor, Abraham Norwood, had built a barn, fence, and stone wall; he demanded that Adams pay him $200 for the barn and 50 cents a rod for the wall and fence.

Norwood harvested hay from the property after Adams had moved in, and then charged the new keeper $14 per ton for hay that Adams needed to feed his cow. “This keeper,” wrote Adams, “has since complained of me, because I decline buying the barn, walling, fencing, and other improvements.”

The 1808 tower lasted until 1839, when a new 44-foot conical rubblestone tower—20 feet in diameter at the base and 10 feet at the top—was built, along with a new one-story granite dwelling, after a congressional appropriation of $5,000 in July 1838. The revolving light was 69 feet above mean high water. A rotating “eclipser” created the appearance of a flash at certain intervals.

The engineer I. W. P. Lewis, in his 1843 report to Congress, wrote that the base of the tower rested on an uneven ledge, the walls were cracked and leaky, the mortar was bad, and the woodwork was decayed. The one-and-one-half- story keeper’s house was also in a deplorable state; the windows were leaky, the cellar had no floor and was wet and muddy, and the entire building was “very defective in materials and workmanship,” according to Lewis.

In a letter in September 1842, John Anderson, superintendent of lighthouses in Maine, had defended the construction of the tower. “I am satisfied that the mortar used was made of good lime,” he wrote, “and sand was not wet with salt water. . . . I appointed an experienced and skillful stone mason of established good reputation.”

John Adams, who had become keeper in 1841 at a yearly salary of $350, provided a statement for Lewis’s report. He was provided a boat, but there was no landing place or shelter for it. Adams’s predecessor, Abraham Norwood, had built a barn, fence, and stone wall; he demanded that Adams pay him $200 for the barn and 50 cents a rod for the wall and fence.

Norwood harvested hay from the property after Adams had moved in, and then charged the new keeper $14 per ton for hay that Adams needed to feed his cow. “This keeper,” wrote Adams, “has since complained of me, because I decline buying the barn, walling, fencing, and other improvements.”

In 1856, the light was changed from white to red so it couldn’t be confused with the lights to the north at Cape Elizabeth.

The problems with the buildings continued; an 1850 inspection, when Stephen Bachelder was keeper, mentioned that the tower and dwelling were both still leaky. In August 1854, Congress appropriated $5,000 for another rebuilding of the tower.

The 1858 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that the work had been completed. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the stone tower. The records for this work aren’t clear, but it seems likely that the tower was extensively renovated and not totally rebuilt. The present wood-frame keeper’s house was also constructed at this time; it has undergone many modifications over the years.

Eben Emerson was keeper from 1861 to 1865. Emerson had been a sailor as a young man. He was said to be a staunch Republican and a dedicated abolitionist, and in his later years he was a beloved character known to all as “Uncle Eben.”

The 1858 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that the work had been completed. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the stone tower. The records for this work aren’t clear, but it seems likely that the tower was extensively renovated and not totally rebuilt. The present wood-frame keeper’s house was also constructed at this time; it has undergone many modifications over the years.

Eben Emerson was keeper from 1861 to 1865. Emerson had been a sailor as a young man. He was said to be a staunch Republican and a dedicated abolitionist, and in his later years he was a beloved character known to all as “Uncle Eben.”

At about 1:00 a.m. on March 16, 1865, Emerson rose from bed to trim the wick in the lighthouse lamp. Through thick fog and heavy surf, Emerson heard frantic voices out on the water.

He tried to launch his boat toward the source of the sounds, but the rough seas made it nearly impossible. The keeper raced to a nearby home on the island and recruited the help of the resident fisherman. The two men were able to launch the light station’s small rowboat, and they soon encountered a brig that had run onto Washburn Ledge. The crewmen were clinging desperately to the rigging as the seas hammered the vessel.

Emerson managed to get aboard the brig. One lifeboat had already been lost, and another still hung by the davits. Emerson urged the men to climb into the lifeboat, while the captain remained at the bow and the mate stood by at the stern. Before returning to his rowboat, Emerson rescued two guinea pigs from below decks and put them in his pockets.

After returning to his boat, Emerson waited for a large wave and yelled, “Cut loose!” The lifeboat rode the wave and the crew escaped safely just before the brig, the Edyth Ann of Nova Scotia, was reduced to kindling by the surf.

For his extraordinary heroism, Emerson was later awarded a plaque and a pair of binoculars from the Canadian government. After his lighthouse- keeping years, Emerson served as a deputy marshal in Biddeford.

Right: The binoculars awarded to Keeper Eben Emerson. Courtesy of the Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse.

Emerson managed to get aboard the brig. One lifeboat had already been lost, and another still hung by the davits. Emerson urged the men to climb into the lifeboat, while the captain remained at the bow and the mate stood by at the stern. Before returning to his rowboat, Emerson rescued two guinea pigs from below decks and put them in his pockets.

After returning to his boat, Emerson waited for a large wave and yelled, “Cut loose!” The lifeboat rode the wave and the crew escaped safely just before the brig, the Edyth Ann of Nova Scotia, was reduced to kindling by the surf.

For his extraordinary heroism, Emerson was later awarded a plaque and a pair of binoculars from the Canadian government. After his lighthouse- keeping years, Emerson served as a deputy marshal in Biddeford.

Right: The binoculars awarded to Keeper Eben Emerson. Courtesy of the Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse.

Albert Norwood became keeper in 1872, and he was in charge in the following year, when Wood Island got its first fog signal, a 1,315-pound bell that sounded single and double blows, alternately, every 25 seconds. The striking machinery was housed in a pyramidal wooden tower.

The bell at Vines Landing

A new 1,200-pound bell was installed in 1890. The 1872 fog bell from Wood Island, manufactured by Vickers, Sons & Co. in England, is now on display (left) at Vines Landing in Biddeford Pool.

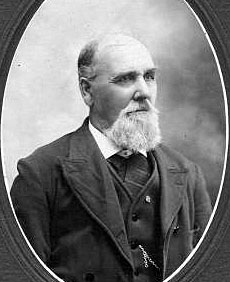

Norwood retired in 1886. Thomas H. Orcutt, a veteran sea captain from Sedgwick, Maine, was keeper from 1886 until his death in 1905. Orcutt played a supporting role in the island’s most infamous tragedy. The principals in the drama were Fred Milliken and Howard Hobbs.

Milliken, a fisherman, game warden, and special policeman in his thirties, lived in a house on Wood Island with his wife and three children for several years in the 1890s. He was described as a giant, in his thirties, who easily carried his dory on his shoulders. Hobbs, a young fisherman, took up residence on the island, sharing a converted chicken house with another fisherman, William Moses. Both Hobbs and Moses were in their early twenties.

Norwood retired in 1886. Thomas H. Orcutt, a veteran sea captain from Sedgwick, Maine, was keeper from 1886 until his death in 1905. Orcutt played a supporting role in the island’s most infamous tragedy. The principals in the drama were Fred Milliken and Howard Hobbs.

Milliken, a fisherman, game warden, and special policeman in his thirties, lived in a house on Wood Island with his wife and three children for several years in the 1890s. He was described as a giant, in his thirties, who easily carried his dory on his shoulders. Hobbs, a young fisherman, took up residence on the island, sharing a converted chicken house with another fisherman, William Moses. Both Hobbs and Moses were in their early twenties.

On June 2, 1896, Hobbs and Moses visited Old Orchard Beach, and they were reportedly intoxicated by the time they returned to Wood Island late in the afternoon.

Right: Keeper Thomas Orcutt, courtesy of the Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse.

Milliken greeted them when they arrived, and he told Hobbs he wanted to speak to him—apparently about an overdue rent payment. Hobbs and Moses returned to their shack. Hobbs picked up his rifle, telling Moses he might shoot some birds. The two young men walked back to Milliken’s property.

Milliken greeted Hobbs and Moses at his garden gate. Milliken asked if the rifle was loaded, and Hobbs replied that it wasn’t. Milliken decided to check for himself. As he stepped toward Hobbs, the younger man fired a shot into Milliken’s chest. Milliken’s wife, who had been watching from the doorway, helped her husband inside and onto a bed. Moses left with Milliken’s young stepson to row ashore with the intention of fetching a doctor.

Milliken died within 45 minutes. In a daze, Hobbs went to the keeper’s dwelling at the lighthouse, where Orcutt advised him to give himself up to the authorities. Hobbs returned to his small shack and proceeded to put a bullet in his own head.

Milliken greeted them when they arrived, and he told Hobbs he wanted to speak to him—apparently about an overdue rent payment. Hobbs and Moses returned to their shack. Hobbs picked up his rifle, telling Moses he might shoot some birds. The two young men walked back to Milliken’s property.

Milliken greeted Hobbs and Moses at his garden gate. Milliken asked if the rifle was loaded, and Hobbs replied that it wasn’t. Milliken decided to check for himself. As he stepped toward Hobbs, the younger man fired a shot into Milliken’s chest. Milliken’s wife, who had been watching from the doorway, helped her husband inside and onto a bed. Moses left with Milliken’s young stepson to row ashore with the intention of fetching a doctor.

Milliken died within 45 minutes. In a daze, Hobbs went to the keeper’s dwelling at the lighthouse, where Orcutt advised him to give himself up to the authorities. Hobbs returned to his small shack and proceeded to put a bullet in his own head.

There are many ghostly tales told about the island, and some blame the 1896 murder-suicide. Some people have claimed the island is cursed.

Left: Ron Kolek of the New England Ghost Project, seen here with Vicki Monroe, conducted an investigation at Wood Island in August 2005. You can read about it here.

Another incident that contributed to this idea was the suicide of another fisherman. After years of solitary island existence, the man went to a hotel in Saco and jumped from a window.

Robert Thayer Sterling, in Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, described another strange incident. Sometime in the late 1800s, a Frenchman who lived on the west side of the island was selling liquor to visiting fishermen. Brawls among the fishermen became commonplace on the island. One of the fights got out of hand, and a drunken fisherman set fire to the Frenchman’s shack. According to Sterling, “The bottles broke and the seething alcoholic blue flames created such a torchlight that it was seen twenty miles at sea.”

Another incident that contributed to this idea was the suicide of another fisherman. After years of solitary island existence, the man went to a hotel in Saco and jumped from a window.

Robert Thayer Sterling, in Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, described another strange incident. Sometime in the late 1800s, a Frenchman who lived on the west side of the island was selling liquor to visiting fishermen. Brawls among the fishermen became commonplace on the island. One of the fights got out of hand, and a drunken fisherman set fire to the Frenchman’s shack. According to Sterling, “The bottles broke and the seething alcoholic blue flames created such a torchlight that it was seen twenty miles at sea.”

In addition to Wood Island’s macabre history, there’s also a brighter tradition of fascinating pets.

Keeper Thomas Orcutt with Sailor, his fog bell ringing dog. Courtesy of Roderick Jeffers.

Keeper Thomas Orcutt’s dog, Sailor, a mostly-black mongrel (described as a Scotch Collie in one article), was taken to the island as a two-month-old puppy and went on to achieve wide fame. In 1894, the Lewiston (Maine) Journal reported:

It is customary for passing steamers to salute the light and the keeper returns it by ringing the bell. The other day a tug whistled three times. The Captain did not hear it, but the dog did. He ran to the door and tried to attract the Captain’s attention by howling. Failing to do this he ran away and then came a second time with no better result. Then he decided to attend to the matter himself, so he seized the rope, which hangs outside, between his teeth and began to ring the bell.

The self-trained Sailor developed the habit of vigorously ringing the bell for every passing vessel. Over the next few years, many passengers aboard local excursion steamers were startled to see the dog’s amazing performances.

It is customary for passing steamers to salute the light and the keeper returns it by ringing the bell. The other day a tug whistled three times. The Captain did not hear it, but the dog did. He ran to the door and tried to attract the Captain’s attention by howling. Failing to do this he ran away and then came a second time with no better result. Then he decided to attend to the matter himself, so he seized the rope, which hangs outside, between his teeth and began to ring the bell.

The self-trained Sailor developed the habit of vigorously ringing the bell for every passing vessel. Over the next few years, many passengers aboard local excursion steamers were startled to see the dog’s amazing performances.

Sailor was said to possess almost human intelligence. He also served as a messenger, delighting in carrying letters and other small articles in his mouth. It was claimed that he understood all that was said to him.

Courtesy of Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse

In 1900, Orcutt remarked, “Sailor and I are old comrades. Wood Island would indeed be a lonely place if I hadn’t the dog to keep me company. He is a bright, intelligent companion and is perfectly content to live the life of a lighthouse keeper away from all dog friends.”

Orcutt died after a brief illness in 1905 at the age of 73. His beloved Sailor had died in his arms just a few months earlier. Orcutt was “well known among the sea faring men and was well liked by all,” according to an obituary. His son-in-law, Levi Jeffers, filled in as keeper until a new one could be appointed.

Charles A. Burke, who stayed until 1914, was the next keeper. In October 1906, several earthquake shocks shook the area. Burke told mainland residents that the island rocked “like the shaking of gelatin pudding” during one of the shocks, but no damage was done.

The last Lighthouse Service keeper at Wood Island Light was Earle Benson, a veteran of World War I who took over when George E. Woodward was transferred in 1934. Benson and his wife, Alice, loved Wood Island the most of their four stations. After a stint at Portland Head Light, where a constant flow of tourists was the norm, the Bensons preferred the quiet of Wood Island. Benson joined the Coast Guard when they it took over the Lighthouse Service in 1939; he became a Chief Boatswain’s Mate and stayed on the island until 1952.

Orcutt died after a brief illness in 1905 at the age of 73. His beloved Sailor had died in his arms just a few months earlier. Orcutt was “well known among the sea faring men and was well liked by all,” according to an obituary. His son-in-law, Levi Jeffers, filled in as keeper until a new one could be appointed.

Charles A. Burke, who stayed until 1914, was the next keeper. In October 1906, several earthquake shocks shook the area. Burke told mainland residents that the island rocked “like the shaking of gelatin pudding” during one of the shocks, but no damage was done.

The last Lighthouse Service keeper at Wood Island Light was Earle Benson, a veteran of World War I who took over when George E. Woodward was transferred in 1934. Benson and his wife, Alice, loved Wood Island the most of their four stations. After a stint at Portland Head Light, where a constant flow of tourists was the norm, the Bensons preferred the quiet of Wood Island. Benson joined the Coast Guard when they it took over the Lighthouse Service in 1939; he became a Chief Boatswain’s Mate and stayed on the island until 1952.

The Coast Guard converted the light station to electricity in 1950. The Bensons were thrilled to replace their battery-operated radio with a television.

Right: Earle Benson, courtesy of the Maine Lighthouse Museum

Their TV watching included the 1950 World Series. “It was so clear you could see the lines on the ball,” said Benson. The Bensons’ favorite TV show was The Lone Ranger.

Wood Island remained a family station under the Coast Guard. Edward G. Frank succeeded Benson as officer in charge in January 1952. Frank moved to the island with his wife, Eloise. A son, Steven, was born that April. The Franks’ daughter, Michele, lived with her grandmother in Vermont to attend school and lived on Wood Island during school vacations.

The Frank family, like many of their predecessors, kept chickens at the station. They also had several pets: a St. Bernard named Henry, a cocker spaniel named Crissey, a Maine coon cat named Timmy, and another cat named Tom. Once, when it seemed that all the chickens had disappeared, Crissey was able to find them in their hiding places in the rocks.

Laurier Burnham, a native of Biddeford, was the keeper for the Coast Guard from 1959 to 1963. Laurier Burnham also served at Halfway Rock Lighthouse and on several lightships during his Coast Guard career. When he died in 1997, his wife recalled, “My husband was very safety conscious. He really knew how to handle a boat.”

The following was received from John Reidy in December 2013:

Around 1964-67, the assigned station keeper was David Bichrest, who lived in the dwelling with his wife and children (two as I recall). At that time, the Island was quite barren, but was the home of many rabbits. Several were acclimated to human presence, as they were often found close to the keeper's dwelling, and were easily approached and petted. I imagine they provided some comic relief for the keeper's children.

In 1966, I was assigned to USCG Station Fletcher's Neck, and served as the designated Relief Keeper at Wood Island, when David Bichrest and family were ashore on leave. I remember the thrills of getting on and off the island, via the wooden, double-ended peapod boat that was kept in the boathouse on the island. There was a pair of wooden rails that extended over the rocks, into the somewhat sheltered waters. Launching the boat was usually not a problem, as gravity was used to lower the boat down these greased rails, simply by detaching the winch cable, climbing aboard, and sliding down into the water. This small boat had an outboard motor on a "canoe bracket" that would be used to approach the awaiting 30’ steel search and rescue boat, or sometimes a 36’ motor lifeboat.

Supplies were loaded into the peapod and personnel then boarded to return to the island. This is when the fun and thrills began. In calm water, the boat operator would simply aim the craft for the center between the rails, with the outboard at full power, and slide uphill on the rails, jump out to attach the winch cable to the bow eye, and then go into the boathouse to energize the electric winch, which would haul the boat up into the boathouse. In less than calm water (most of the time), however, waves always seemed to run across the rails rather than straight at them. The boat operator had to study these waves to determine their set, and adjust his aim accordingly. A slight miscalculation or a rogue wave could result in missing the rails, and dumping the boat sideways off them and, worse yet, onto the rocks. There was not a lot of room for error.

Once safely on the island, the task of loading supplies into a cart, and the long tractor pull up the ramp to the dwelling could begin. This was sometimes challenging, particularly during winter, as the ramps were sometimes covered with snow and ice. These ramps were not level in some areas of the trek, so it was occasionally necessary to spread some salted sand to reach the destination.

At the station itself, there was always much to do. The main duty, of course, was turning the light on at dusk and off at sunrise. Then the fog signal had to be activated whenever conditions required. Both of these operations were done manually, for there were no automated controls at that time. During the day, after extinguishing the light, the lenses were cleaned, the brass polished, and then a protective cloth cover was placed over the Fresnel lens, and removed again each night. The "Stars & Stripes" were also raised and lowered daily.

When the weather permitted, there was always something that needed a little touch-up painting, either on the dwelling or the light tower as well as the boathouse. Water was another concern that required daily monitoring. There were two concrete cisterns in the basement of the keeper’s house, which held well water and also rainwater collected from the roof. Water levels were checked and purity was also monitored and recorded in the station logbook. Housekeeping duty was a daily chore, performed by the relief keepers as well as the permanent persons. There was an emergency generator that was test run weekly for an hour, to assure proper operation for those times when the shore power failed. Maintenance of the winch motor at the boathouse was also performed, and frequent inspection of the ¾-mile wooden ramp and its supports was also necessary. During the summer there was grass to mow and scrub brush to prune and trim. In the winter, there was always snow and ice to deal with.

Their TV watching included the 1950 World Series. “It was so clear you could see the lines on the ball,” said Benson. The Bensons’ favorite TV show was The Lone Ranger.

Wood Island remained a family station under the Coast Guard. Edward G. Frank succeeded Benson as officer in charge in January 1952. Frank moved to the island with his wife, Eloise. A son, Steven, was born that April. The Franks’ daughter, Michele, lived with her grandmother in Vermont to attend school and lived on Wood Island during school vacations.

The Frank family, like many of their predecessors, kept chickens at the station. They also had several pets: a St. Bernard named Henry, a cocker spaniel named Crissey, a Maine coon cat named Timmy, and another cat named Tom. Once, when it seemed that all the chickens had disappeared, Crissey was able to find them in their hiding places in the rocks.

Laurier Burnham, a native of Biddeford, was the keeper for the Coast Guard from 1959 to 1963. Laurier Burnham also served at Halfway Rock Lighthouse and on several lightships during his Coast Guard career. When he died in 1997, his wife recalled, “My husband was very safety conscious. He really knew how to handle a boat.”

The following was received from John Reidy in December 2013:

Around 1964-67, the assigned station keeper was David Bichrest, who lived in the dwelling with his wife and children (two as I recall). At that time, the Island was quite barren, but was the home of many rabbits. Several were acclimated to human presence, as they were often found close to the keeper's dwelling, and were easily approached and petted. I imagine they provided some comic relief for the keeper's children.

In 1966, I was assigned to USCG Station Fletcher's Neck, and served as the designated Relief Keeper at Wood Island, when David Bichrest and family were ashore on leave. I remember the thrills of getting on and off the island, via the wooden, double-ended peapod boat that was kept in the boathouse on the island. There was a pair of wooden rails that extended over the rocks, into the somewhat sheltered waters. Launching the boat was usually not a problem, as gravity was used to lower the boat down these greased rails, simply by detaching the winch cable, climbing aboard, and sliding down into the water. This small boat had an outboard motor on a "canoe bracket" that would be used to approach the awaiting 30’ steel search and rescue boat, or sometimes a 36’ motor lifeboat.

Supplies were loaded into the peapod and personnel then boarded to return to the island. This is when the fun and thrills began. In calm water, the boat operator would simply aim the craft for the center between the rails, with the outboard at full power, and slide uphill on the rails, jump out to attach the winch cable to the bow eye, and then go into the boathouse to energize the electric winch, which would haul the boat up into the boathouse. In less than calm water (most of the time), however, waves always seemed to run across the rails rather than straight at them. The boat operator had to study these waves to determine their set, and adjust his aim accordingly. A slight miscalculation or a rogue wave could result in missing the rails, and dumping the boat sideways off them and, worse yet, onto the rocks. There was not a lot of room for error.

Once safely on the island, the task of loading supplies into a cart, and the long tractor pull up the ramp to the dwelling could begin. This was sometimes challenging, particularly during winter, as the ramps were sometimes covered with snow and ice. These ramps were not level in some areas of the trek, so it was occasionally necessary to spread some salted sand to reach the destination.

At the station itself, there was always much to do. The main duty, of course, was turning the light on at dusk and off at sunrise. Then the fog signal had to be activated whenever conditions required. Both of these operations were done manually, for there were no automated controls at that time. During the day, after extinguishing the light, the lenses were cleaned, the brass polished, and then a protective cloth cover was placed over the Fresnel lens, and removed again each night. The "Stars & Stripes" were also raised and lowered daily.

When the weather permitted, there was always something that needed a little touch-up painting, either on the dwelling or the light tower as well as the boathouse. Water was another concern that required daily monitoring. There were two concrete cisterns in the basement of the keeper’s house, which held well water and also rainwater collected from the roof. Water levels were checked and purity was also monitored and recorded in the station logbook. Housekeeping duty was a daily chore, performed by the relief keepers as well as the permanent persons. There was an emergency generator that was test run weekly for an hour, to assure proper operation for those times when the shore power failed. Maintenance of the winch motor at the boathouse was also performed, and frequent inspection of the ¾-mile wooden ramp and its supports was also necessary. During the summer there was grass to mow and scrub brush to prune and trim. In the winter, there was always snow and ice to deal with.

Wood Island was considered briefly as a possible site for a nuclear power plant in the late 1960s. In 1970, 28 of the island's 35 acres were deeded to the Maine Audubon Society.

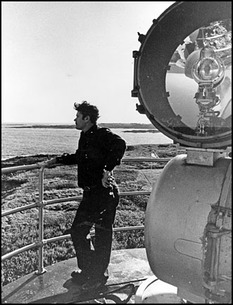

Left: A Coast Guard keeper at the top of Wood Island Lighthouse circa 1977. Courtesy of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

In July 1976, Coast Guardsman Mike McQuade and his wife Patsy, natives of Omaha, Nebraska, came to the island. McQuade had asked for lighthouse duty, and he was pleased when he was assigned to Wood Island Light Station. "We couldn't have asked for a better place to be near the ocean," he said.

In addition to operating the light, McQuade was required to turn on the station's fog signal when the visibility dropped to less than 2 1/2 miles, and he also had to keep an eye on 20 navigational buoys near the island.

The McQuades inherited the station's mascot, a five-year-old collie named Kelly. Kelly came to Wood Island Light as a puppy and performed the important duty of keeping rats and mice under control. The McQuades also brought along Torrey, their Lhasa Apso. In 1978, the McQuades welcomed their first child, Damian, born on the mainland at Webber Hospital in Biddeford.

In July 1976, Coast Guardsman Mike McQuade and his wife Patsy, natives of Omaha, Nebraska, came to the island. McQuade had asked for lighthouse duty, and he was pleased when he was assigned to Wood Island Light Station. "We couldn't have asked for a better place to be near the ocean," he said.

In addition to operating the light, McQuade was required to turn on the station's fog signal when the visibility dropped to less than 2 1/2 miles, and he also had to keep an eye on 20 navigational buoys near the island.

The McQuades inherited the station's mascot, a five-year-old collie named Kelly. Kelly came to Wood Island Light as a puppy and performed the important duty of keeping rats and mice under control. The McQuades also brought along Torrey, their Lhasa Apso. In 1978, the McQuades welcomed their first child, Damian, born on the mainland at Webber Hospital in Biddeford.

In 1972, Wood Island Light's lantern was removed and a rotating aerobeacon was installed. The public complained about the "headless" lighthouse so a new aluminum lantern was installed when the light was automated and the keeper and his family were removed in 1986.

Wood Island Light during its "headless" period. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

In early 2003, a chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation was formed to care for the light station. The group, Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse (FOWIL), has been working for a full restoration of the lighthouse tower, keeper’s house, boathouse, and oil house. FOWIL also takes care of the wooden boardwalk from the boathouse to the keeper’s house and seven acres of land at the light station.

New handrails were installed in the lighthouse tower in 2008. In the fall of 2009, FOWIL contracted Stone Age Masonry to carry out the restoration of the lighthouse tower. FOWIL worked with architects and Maine state officials to establish a restoration plan. The work was completed in the summer of 2010.

The exterior of the keeper's house was restored by Leslie Masonry in 2011. The $200,000 project included the restoration of the porch to its 1906 design. The covered walkway between the house and tower was restored in 2012.

New handrails were installed in the lighthouse tower in 2008. In the fall of 2009, FOWIL contracted Stone Age Masonry to carry out the restoration of the lighthouse tower. FOWIL worked with architects and Maine state officials to establish a restoration plan. The work was completed in the summer of 2010.

The exterior of the keeper's house was restored by Leslie Masonry in 2011. The $200,000 project included the restoration of the porch to its 1906 design. The covered walkway between the house and tower was restored in 2012.

Above: Two views from the top of the tower.

Below: Inside the restored keeper's house

Below: Inside the restored keeper's house

In the summer season, boat tours are offered to the island and light station from Vines Landing in Biddeford Pool. The tours take about 90 minutes. Click here for more information.

This LED optic was installed in late 2012

Most of the rest of the island is managed by the Maine Audubon Society, and some of it is privately owned. Wood Island Light, still an active aid to navigation, can be seen from a trail along the water in Biddeford Pool and distantly from the Old Orchard Beach area.

Keepers: (Thanks to the Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse for their help with this list. This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Benjamin Cole (1808-1809); Philip Goldthwaite (1809-1832); Tristam Goldthwaite (1832-1833); Abraham Norwood (1833-1841); John Adams (1841-1849?); Stephen D. Batchelder (1849-?); Nathaniel Varrell (185?); L.F. Varrell (185?); Joseph R. Bryant (1854-1861?) ; Ebenezer Emerson (1861-1865); Edwin Tarbox (1865- 1872); Albert Norwood (1872-1886); Thomas Henry Orcutt (1886-1905); Charles A. Burke (1905-1914); C.B. Staples (1914-1917); W. F. Lurvey (1917-1923); Albert Staples (1923-1926); George Woodward (1927-1934); Earle Benson (Lighthouse Service 1934-1939, Coast Guard 1939-1952)

U.S. COAST GUARD: EN3 Edward G. Frank (1952-1956); BM2 Forrest S. Cheney (1952); BM3 Edwin R. Duquette (1952); SN R. M. Sawtelle (1952-1954); John Rogers (Rodgers?) (c. 1948); BM2 Gerald E. Ryan (1957); EN3 David G. Crider (1957); EN3 Harrison E. Parker (1957); BM3 David A Katon (1957-1959); FN Bruce A. Creswell (1958); SN Richard M. Gramlich (1958); SN Constantine H. Szczechowicz (1958, 1961); EN2 Laurier Burnham (1959-1963); Edward J. Conner (1959); SN Spencer N. Graham (1959-1960); BM1 Lee Merrick (1960); Raymond E. Bill, Sr. (1961); ENS Bryon H. Stauffer (1961); BM1 James E. Murray (1961); SA Alan L. George (1961-1962); Wasil W. Johnson (1962); BM3 Frank D. Harmon (1962); SN Martin P. Hass (1962); BM1 Jack B. Netherwood (1962-1963); Roger O. Shaw (1962-1963); EN2 David Winchester (1963-1964); SNCS James Willis (1963-1964); SN Clifton M. Wood (1963-1964); EN2 David P. Bichrest (1964-1967); George Tevis (1965); Perley Sprague (1965, 1968); EN3 John P. Reidy (relief keeper 1966-1967); BM3 A.J. Savageau (sp?) (1967-1968); BM2 Ronald A. Handfield (1968); EN2 James J. Roche (1968-1969); Clifford Trebilcock (1970-1971); Andrew Preneau (1972); Jerry Murray (1973-1976); Michael McQuade (1976-1979); Russ Lowell (1979-1982); Phillip Brothwell (1983-1985); Merton Perry (1986); Warren Rowell (1986).

Keepers: (Thanks to the Friends of Wood Island Lighthouse for their help with this list. This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Benjamin Cole (1808-1809); Philip Goldthwaite (1809-1832); Tristam Goldthwaite (1832-1833); Abraham Norwood (1833-1841); John Adams (1841-1849?); Stephen D. Batchelder (1849-?); Nathaniel Varrell (185?); L.F. Varrell (185?); Joseph R. Bryant (1854-1861?) ; Ebenezer Emerson (1861-1865); Edwin Tarbox (1865- 1872); Albert Norwood (1872-1886); Thomas Henry Orcutt (1886-1905); Charles A. Burke (1905-1914); C.B. Staples (1914-1917); W. F. Lurvey (1917-1923); Albert Staples (1923-1926); George Woodward (1927-1934); Earle Benson (Lighthouse Service 1934-1939, Coast Guard 1939-1952)

U.S. COAST GUARD: EN3 Edward G. Frank (1952-1956); BM2 Forrest S. Cheney (1952); BM3 Edwin R. Duquette (1952); SN R. M. Sawtelle (1952-1954); John Rogers (Rodgers?) (c. 1948); BM2 Gerald E. Ryan (1957); EN3 David G. Crider (1957); EN3 Harrison E. Parker (1957); BM3 David A Katon (1957-1959); FN Bruce A. Creswell (1958); SN Richard M. Gramlich (1958); SN Constantine H. Szczechowicz (1958, 1961); EN2 Laurier Burnham (1959-1963); Edward J. Conner (1959); SN Spencer N. Graham (1959-1960); BM1 Lee Merrick (1960); Raymond E. Bill, Sr. (1961); ENS Bryon H. Stauffer (1961); BM1 James E. Murray (1961); SA Alan L. George (1961-1962); Wasil W. Johnson (1962); BM3 Frank D. Harmon (1962); SN Martin P. Hass (1962); BM1 Jack B. Netherwood (1962-1963); Roger O. Shaw (1962-1963); EN2 David Winchester (1963-1964); SNCS James Willis (1963-1964); SN Clifton M. Wood (1963-1964); EN2 David P. Bichrest (1964-1967); George Tevis (1965); Perley Sprague (1965, 1968); EN3 John P. Reidy (relief keeper 1966-1967); BM3 A.J. Savageau (sp?) (1967-1968); BM2 Ronald A. Handfield (1968); EN2 James J. Roche (1968-1969); Clifford Trebilcock (1970-1971); Andrew Preneau (1972); Jerry Murray (1973-1976); Michael McQuade (1976-1979); Russ Lowell (1979-1982); Phillip Brothwell (1983-1985); Merton Perry (1986); Warren Rowell (1986).