History of Clarks Point Light, New Bedford, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Clarks Point is the southernmost extension of the city of New Bedford, in Buzzards Bay on the west side of the entrance to the Acushnet River and New Bedford Harbor. The area's fledgling whaling industry flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, making New Bedford one of the richest cities in the world.

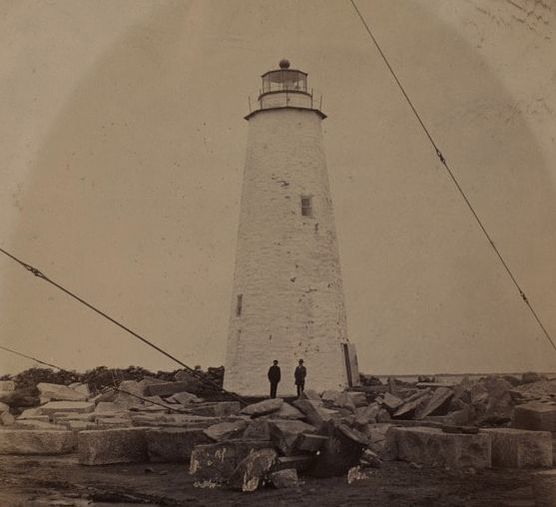

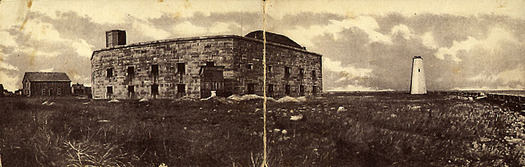

The 1804 Clark's Point Lighthouse circa 1859 (National Archives)

Clarks Point was an ideal location for a navigational aid to help mariners heading to New Bedford. Local merchants erected the first wooden lighthouse on the point in 1797. Daniel Ricketson described the building of the lighthouse in his 1858 book, The History of New Bedford: “A wooden lighthouse was built at Clark's Point, at the raising of which, to induce the people to assist, and for the sake of a general jollification at so important an event, a hundred gallon try-pot of chowder, with other entertainment, was prepared. Much to the credit of the sobriety of our predecessors, no one became intoxicated on this occasion."

Little is known of the structure, which burned down about a year later. Ricketson wrote that the fire took place during a thunderstorm and was probably the result of the tower being hit by lightning, or possibly a seabird crashing through the lantern glass and upsetting the lamps. The lighthouse was promptly rebuilt, financed by local merchants and mariners.

Little is known of the structure, which burned down about a year later. Ricketson wrote that the fire took place during a thunderstorm and was probably the result of the tower being hit by lightning, or possibly a seabird crashing through the lantern glass and upsetting the lamps. The lighthouse was promptly rebuilt, financed by local merchants and mariners.

The Columbian Courier of October 16, 1799, reported that the lighthouse had been completed and lighted for the first time on October 12.

The 1804 tower with its 1865 lantern (New Bedford Public Library)

A bill was passed in the spring of 1800, stating that stated that the lighthouse would thereafter be supported at the expense of the United States. Another fire, apparently caused by lightning, destroyed the tower on August 5, 1803. It took until the following March for Congress to appropriate $2,500 for yet another rebuilding.

An octagonal rubblestone tower, 38 feet tall, was completed in 1804. The lighthouse underwent extensive renovations in 1818, including an increase of 4 feet in height and the installation of a new octagonal iron lantern. A fixed light was exhibited, 52 feet above the sea.

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Lt. Edward W. Carpender inspected the lighthouse in 1838. He noted that a dwelling was not provided for the keeper, who lived in his own house. Carpender believed the lighthouse would have been of greater service to navigation if it had been erected about 150 yards farther to the south, on the southwestern point of Egg Island Shoal.

He also felt that the ten oil lamps in the lighthouse could be judiciously reduced to six.

An octagonal rubblestone tower, 38 feet tall, was completed in 1804. The lighthouse underwent extensive renovations in 1818, including an increase of 4 feet in height and the installation of a new octagonal iron lantern. A fixed light was exhibited, 52 feet above the sea.

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Lt. Edward W. Carpender inspected the lighthouse in 1838. He noted that a dwelling was not provided for the keeper, who lived in his own house. Carpender believed the lighthouse would have been of greater service to navigation if it had been erected about 150 yards farther to the south, on the southwestern point of Egg Island Shoal.

He also felt that the ten oil lamps in the lighthouse could be judiciously reduced to six.

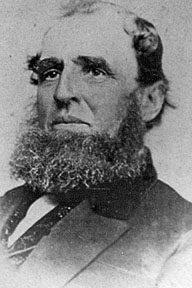

Edward W. Howland became keeper in early 1835, replacing his father, Captain Capt. Cornelius Howland, who had recently died at 77.

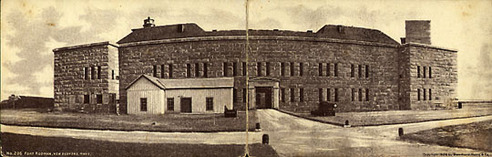

Fort Taber

The elder Howland was born in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, and was master of a vessel by the age of 18. He was taken prisoner during the Revolution and survived 15 months of captivity in Edinburgh Castle. Howland had some gold hidden away while he was held prisoner, and he used it to bribe a cleaning woman. Disguised in one of the woman’s dresses, Howland escaped and boarded a vessel bound for Holland.After more adventures, Captain. Howland settled down on a farm at Clark’s Point, and eventually received the lighthouse keeping appointment. Daniel Ricketson remembered him as a “fresh, healthy-looking man” in his old age, who “well represented the old school of the primitive Dartmouth Friends [Quakers].”

Henry Smith, who became keeper in 1843, was a woodcarver of figureheads for New Bedford’s whaling fleet. An 1851 report described the station under Smith: “Everything clean; cast-iron floor to lantern.”

In 1851, a new cast iron deck was added, and new lamps and reflectors were installed. The tower still had its 1818 lantern -- the last remaining "old-style lantern" in the district, according to the Lighthouse Board -- a dozen years later, but the lantern and lighting apparatus were replaced in 1865.

In 1857, a new fort began to take shape next to the lighthouse. Cannons were in place and the fort's granite walls were largely complete by 1863, but the fort was considered obsolete after the Civil War and its planned three tiers were never finished.

The fort was known as Fort Taber in honor of the city's mayor in the early 1860s Isaac C. Taber; it was officially renamed Fort Rodman in 1898. Most local residents still know it as Fort Taber.

Henry Smith, who became keeper in 1843, was a woodcarver of figureheads for New Bedford’s whaling fleet. An 1851 report described the station under Smith: “Everything clean; cast-iron floor to lantern.”

In 1851, a new cast iron deck was added, and new lamps and reflectors were installed. The tower still had its 1818 lantern -- the last remaining "old-style lantern" in the district, according to the Lighthouse Board -- a dozen years later, but the lantern and lighting apparatus were replaced in 1865.

In 1857, a new fort began to take shape next to the lighthouse. Cannons were in place and the fort's granite walls were largely complete by 1863, but the fort was considered obsolete after the Civil War and its planned three tiers were never finished.

The fort was known as Fort Taber in honor of the city's mayor in the early 1860s Isaac C. Taber; it was officially renamed Fort Rodman in 1898. Most local residents still know it as Fort Taber.

The high walls of the fort eventually blocked the view of the light. In 1869, a rectangular wooden tower was erected on the northerly tower of the fort.

The lantern from the old stone tower was relocated to the new structure, and the new light went into service on June 15, 1869. In its new position, the light was 68 feet above the sea. The old stone tower remained standing until 1906, when it was demolished.

In 1898, the establishment of Butler Flats Light offshore rendered Clarks Point Light obsolete. The light on the fort was discontinued in April 1898. Capt. Amos C. Baker, Jr., keeper of the light at Clarks Point since 1880, became the first keeper at Butler Flats.

In 1898, the establishment of Butler Flats Light offshore rendered Clarks Point Light obsolete. The light on the fort was discontinued in April 1898. Capt. Amos C. Baker, Jr., keeper of the light at Clarks Point since 1880, became the first keeper at Butler Flats.

The fort and lighthouse were restored in the early 1970s, only to fall victim to extensive vandalism and theft. The lighthouse gradually became a shabby ruin.

C. 1900. The old tower can be seen to the right and the 1869 lighthouse can be seen on the fort.

In July 1997, the City of New Bedford unveiled an ambitious plan to create a new public park around the fort. Fort Taber Park includes more than a mile of trails-with 180-degree views of the harbor-for walking and biking.

A group called the Fort Taber Historical Association is actively involved in the preservation of the fort.

City officials also decided to fully restore and relight the historic lighthouse on the fort. Restoration was carried out during the winter months of 2000-01 inside the city's wastewater treatment plant's welding facility. The wood-frame upper portion of the lighthouse was rebuilt by city crews.

A group called the Fort Taber Historical Association is actively involved in the preservation of the fort.

City officials also decided to fully restore and relight the historic lighthouse on the fort. Restoration was carried out during the winter months of 2000-01 inside the city's wastewater treatment plant's welding facility. The wood-frame upper portion of the lighthouse was rebuilt by city crews.

Restoration was funded in part by a grant from the utility company Nstar.

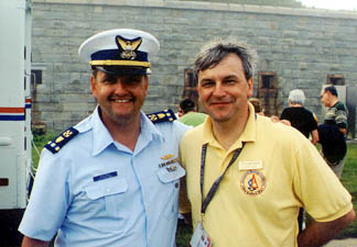

Courtesy of New Bedford Department of Tourism and Marketing

A gala relighting ceremony was held on the evening of Friday, June 15, 2001-the 132nd anniversary of the lighthouse's first illumination.

Approximately 3,000 people attended the event. The program included a seaside pops concert by the New Bedford Symphony Orchestra, a special postal cancellation, and remarks from city, state, and federal representatives.

Capt. Gerald M. Davis, chief of staff of the First Coast Guard District, delivered the keynote address. The Coast Guard presented New Bedford Mayor Frederick Kalisz with a meritorious public service award, and Tim Harrison, president of the American Lighthouse Foundation, presented the Mayor with a "Keeper of the Light" award.

For the city of New Bedford, this was the third lighthouse restoration in three years, following the successful relightings of the Butler Flats and Palmer Island lights.

The light was switched on by New Bedford's director of Tourism and Marketing, Arthur Motta, at 9:00 p.m., followed by cannons blasting, fireworks in the air, and the playing of the 1812 Overture.

NOTE: As of October 2015, the light is no longer functioning.

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Cornelius Howland (?-1835), Edward W. Howland (1835-43), Henry M. Smith (1843-1873), Amos Baker (1873-1880); Amos C. Baker Jr. (1880-1898) |