History of White Island Lighthouse, Isles of Shoals, New Hampshire

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

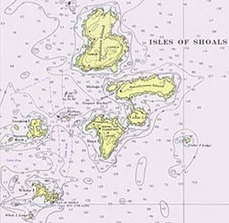

The Isles of Shoals, a cluster of nine islands located several miles off the seacoast of New Hampshire and southern Maine, were described by Robert Thayer Sterling in Maine Lighthouses and the Men Who Keep Them as "a low lying group apparently composed of masses of tumbled granite bleached white by the unceasing beating of the storm king and the glare of the blazing sun."

The islands were frequented by European fishermen for years before Capt. John Smith explored them in 1614. Smith named the islands "Smith's Isles" after himself.

According to some accounts, fishermen named the islands after their resemblance to a school, or shoal, of fish. Others say the name originated beacuse of the "shoaling," or schooling, of fish, especially mackerel and herring, around them. The area remained an important fishing center for centuries.

In May 1820, Congress authorized $5000 for a lighthouse in the Isles of Shoals. The local customs collector, Timothy Upham, surveyed the islands with some local ship captains in the following month.

Upham wrote a letter to Stephen Pleasanton, who was in charge of the nation's lighthouses:

According to some accounts, fishermen named the islands after their resemblance to a school, or shoal, of fish. Others say the name originated beacuse of the "shoaling," or schooling, of fish, especially mackerel and herring, around them. The area remained an important fishing center for centuries.

In May 1820, Congress authorized $5000 for a lighthouse in the Isles of Shoals. The local customs collector, Timothy Upham, surveyed the islands with some local ship captains in the following month.

Upham wrote a letter to Stephen Pleasanton, who was in charge of the nation's lighthouses:

After examining carefully all the islands, rocks and shoals, it was the opinion of the gentlemen present that White Island, the southwestern-most of the group, laying in a direct line between Cape Ann (the most prominent headland on this coast) and Portsmouth harbor, was the most suitable, and in fact, the only proper place on which to erect a lighthouse. This island is uninhabited and belongs to New Hampshire.

The first lighthouse in the Isles of Shoals was subsequently built on White Island in 1820, and it went into service in January 1821. It was a stone tower, later encased with wood and shingled.

The contract called for the builders, carpenter Jonathan Folsom and mason William Palmer, to construct a 40-foot tower of "undressed stone, laid in good lime mortar," with a diameter at the base of 22 feet and 10.5 feet at the top. Under a separate contract, Folsom built a covered walkway that provided safe passage over the rocks between the dwelling and tower. Various versions of the walkway have been destroyed by storms; there have been at least six structures over the years.

Winslow Lewis installed the original wrought-iron lantern and lighting equipment, which consisted of 15 lamps arranged in a triangular framework. The lighthouse's original characteristic was unusually patriotic, with red, white, and blue flashes. The blue flash was discontinued in the 1830s because of its relatively poor visibility.

The contract called for the builders, carpenter Jonathan Folsom and mason William Palmer, to construct a 40-foot tower of "undressed stone, laid in good lime mortar," with a diameter at the base of 22 feet and 10.5 feet at the top. Under a separate contract, Folsom built a covered walkway that provided safe passage over the rocks between the dwelling and tower. Various versions of the walkway have been destroyed by storms; there have been at least six structures over the years.

Winslow Lewis installed the original wrought-iron lantern and lighting equipment, which consisted of 15 lamps arranged in a triangular framework. The lighthouse's original characteristic was unusually patriotic, with red, white, and blue flashes. The blue flash was discontinued in the 1830s because of its relatively poor visibility.

The colored lights were originally produced by the use of colored liquid in "globe tubes." That system was replaced by colored glass panels in the lantern by sometime in the 1830s.

The first White Island Lighthouse, circa late 1850s. (U.S. Coast Guard)

The original lantern was replaced by a new octagonal iron lantern in 1836. The work was again performed by Winslow Lewis.

The nation's first fog bell, at West Quoddy Head in Maine, had just been established a few months earlier. White Island received a fog bell that was mounted with striking machinery inside the lighthouse tower. The 806-pound bell was cast by Joseph W. Revere, the son of Paul Revere. The bell could not be heard above the thunderous surf, so it was discontinued in 1823.

The first keeper was Clement Jackson, a local merchant. Jackson had to pay a helper, and his requests for a raise went unheeded. When he resigned in 1824, Jackson was succeeded by a native Shoaler, shipmaster Benjamin Haley. Haley was only 33 years old when he died in 1829.

Joseph L. Locke of Rye, New Hampshire, was the keeper from 1829 to 1839.

The nation's first fog bell, at West Quoddy Head in Maine, had just been established a few months earlier. White Island received a fog bell that was mounted with striking machinery inside the lighthouse tower. The 806-pound bell was cast by Joseph W. Revere, the son of Paul Revere. The bell could not be heard above the thunderous surf, so it was discontinued in 1823.

The first keeper was Clement Jackson, a local merchant. Jackson had to pay a helper, and his requests for a raise went unheeded. When he resigned in 1824, Jackson was succeeded by a native Shoaler, shipmaster Benjamin Haley. Haley was only 33 years old when he died in 1829.

Joseph L. Locke of Rye, New Hampshire, was the keeper from 1829 to 1839.

Locke and his wife had six children when they moved to the island, and three more were born during Locke's decade as keeper. He sometimes hired other people to help with the lightkeeping duties, and there were complaints that the keeper was often away on the mainland.

I received the following message from Joe Kenick Jr. in July 2011:

My now 101-year-old Mom has taught us that a White Island light keeper in the 1830s was William Randall. His wife, Eliza G. Randall, died there at age 40 in September 1836 leaving him with a very young baby. I'm told he rowed her body over to Star and wrote in his journal, "There isn't enough dirt on White Island to bury a mackerel." She is buried next to one of the young Caswell women and has head and foot stones that match several of the Caswell ones.

Mr. Randall turned his infant son over to his (or Eliza's, I'm vague on this) sister who was married into the Waldron family. That baby, known as Benjamin Franklin Waldron became the father of Mina Waldron Frost Fifield, who became the mother of my Mom, Pauline Fifield Kenick. Whenever I visit the Shoals I visit her grave, bring flowers and pray there.

My now 101-year-old Mom has taught us that a White Island light keeper in the 1830s was William Randall. His wife, Eliza G. Randall, died there at age 40 in September 1836 leaving him with a very young baby. I'm told he rowed her body over to Star and wrote in his journal, "There isn't enough dirt on White Island to bury a mackerel." She is buried next to one of the young Caswell women and has head and foot stones that match several of the Caswell ones.

Mr. Randall turned his infant son over to his (or Eliza's, I'm vague on this) sister who was married into the Waldron family. That baby, known as Benjamin Franklin Waldron became the father of Mina Waldron Frost Fifield, who became the mother of my Mom, Pauline Fifield Kenick. Whenever I visit the Shoals I visit her grave, bring flowers and pray there.

In 1838, this was nearly one of the first American lighthouses to have a Fresnel lens installed, but it was decided that the tower was too low for a satisfactory test of the lens.

In October 1839, Thomas Laighton (1805-1866) became keeper. He and his brother Joseph had bought four of the islands in the Isles of Shoals including the largest, Hog (later known as Appledore), and Smuttynose. Laighton was a former selectman and New Hampshire state senator.

Laighton and his wife, Eliza, moved to White Island with their two children, Oscar and Celia. In 1841 a baby, Cedric, was born to the Laightons at the lighthouse. On his arrival, Laighton wrote in his journal:

The internal apparatus and machinery of the Lighthouse require some attention. The reflectors are so much worn and otherwise injured that I should think quite one half of the light from the lamps is absorbed . . . The machinery for turning the apparatus connected with the lamps is cumbrous and constantly liable to disorder. . .

Another new lantern and lighting apparatus were installed in late 1840 by Winslow Lewis. In 1842, engineer I.W.P. Lewis inspected the station and reported, "The whole construction of the apparatus bears the mark of rude workmanship." The lamps and reflectors weren't replaced by a more efficient Fresnel lens until 1855.

Laighton and his wife, Eliza, moved to White Island with their two children, Oscar and Celia. In 1841 a baby, Cedric, was born to the Laightons at the lighthouse. On his arrival, Laighton wrote in his journal:

The internal apparatus and machinery of the Lighthouse require some attention. The reflectors are so much worn and otherwise injured that I should think quite one half of the light from the lamps is absorbed . . . The machinery for turning the apparatus connected with the lamps is cumbrous and constantly liable to disorder. . .

Another new lantern and lighting apparatus were installed in late 1840 by Winslow Lewis. In 1842, engineer I.W.P. Lewis inspected the station and reported, "The whole construction of the apparatus bears the mark of rude workmanship." The lamps and reflectors weren't replaced by a more efficient Fresnel lens until 1855.

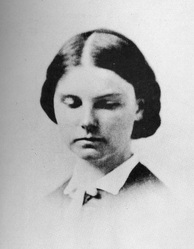

Laighton's daughter, Celia, later gained widespread fame as Celia Thaxter, poet and author.

Celia Thaxter

In her book, Among the Isles of Shoals, she described the family's arrival at White Island:

It was at sunset in autumn that we were set ashore on that loneliest, lovely rock, where the lighthouse looked down on us like some tall, black-capped giant, and filled me with awe and wonder. At its base a few goats were grouped on the rock, standing out against the red sky as I looked up at them...

Some one began to light the lamps in the tower. Rich red and golden, they swung around in mid-air; everything was strange and fascinating and new.

She wrote about an evening visit to the water's edge:

High above, the lighthouse rays streamed out into the humid dark, and the cottage windows were ruddy from the glow within. I felt so much a part of the Lord's universe, I was no more afraid of the dark than the wave or the winds.

It was at sunset in autumn that we were set ashore on that loneliest, lovely rock, where the lighthouse looked down on us like some tall, black-capped giant, and filled me with awe and wonder. At its base a few goats were grouped on the rock, standing out against the red sky as I looked up at them...

Some one began to light the lamps in the tower. Rich red and golden, they swung around in mid-air; everything was strange and fascinating and new.

She wrote about an evening visit to the water's edge:

High above, the lighthouse rays streamed out into the humid dark, and the cottage windows were ruddy from the glow within. I felt so much a part of the Lord's universe, I was no more afraid of the dark than the wave or the winds.

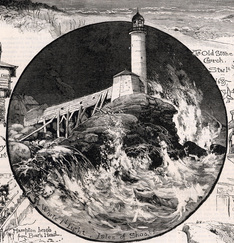

Storms frequently swept over White Island. One particularly severe gale struck in December 1839. The wooden sheathing was torn from the lighthouse and the covered walkway between the house and tower -- which had just been rebuilt in the previous year -- was destroyed. The barn was also demolished by the storm, but Laighton was able to save the family's cow by moving her into the house.

During the same storm, the brig Pocahontas was wrecked on a nearby sandbar and all aboard perished. The memory of this incident inspired Celia Thaxter's poem, The Wreck of the Pocahontas, which read, in part:

Celia Thaxter

I lit the lamps in the lighthouse tower,

For the sun dropped down and the day was dead.

They shone like a glorious clustered flower,

Ten golden and five red.

Like all the demons loosed at last,

Whistling and shrieking, wild and wide,

The mad wind raged, while strong and fast

Rolled in the rising tide.

The thick storm seemed to break apart

To show us, staggering to her grave,

The fated brig. We had no heart

To look, for naught could save.

When Whig William Henry Harrison was elected president in 1840, Laighton, who was an active Democrat, lost his job.

Joseph Cheever served as keeper from 1841 until Laighton was re-appointed in 1843. During that time, Laighton and his family lived on Smuttynose Island. Richard Henry Dana, author of Two Years Before the Mast, visited during Cheever's tenure in August 1843 and wrote in Vacation Rambles:

Cheever took me over to his lighthouse, and as the weather looked rather threatening, I consented to spend the night. His wife is a very pretty young woman, under thirty, and he has three children. . . He has taken great pains to perform his duties well, and being an intelligent, temperate man . . . has filled his place better than it has ever been filled. . . His salary is $600 per annum, out of which he has to pay for an assistant whom he is obliged to keep always on the island in case of sickness or accident to himself, and to support his family. Lately the collector of the customs at Portsmouth, by whom he is appointed, had him removed and a Tyler man put in his place. Cheever now trembles in his shoes and is utterly at a loss to know what to do.”

Cheever took me over to his lighthouse, and as the weather looked rather threatening, I consented to spend the night. His wife is a very pretty young woman, under thirty, and he has three children. . . He has taken great pains to perform his duties well, and being an intelligent, temperate man . . . has filled his place better than it has ever been filled. . . His salary is $600 per annum, out of which he has to pay for an assistant whom he is obliged to keep always on the island in case of sickness or accident to himself, and to support his family. Lately the collector of the customs at Portsmouth, by whom he is appointed, had him removed and a Tyler man put in his place. Cheever now trembles in his shoes and is utterly at a loss to know what to do.”

Laighton was back as keeper a short time later. In times of rough weather, the residents of White Island were frequently cut off from the mainland. A pilot boat brought mail and supplies every week or ten days.

Oscar Laighton

Once a year Eliza Laighton traveled to Portsmouth to buy materials to make clothing for her family. A few times a year the lighthouse inspector would come, bringing oil for the lamps and other supplies, sometimes including a barrel of pork.

Celia's brother, Oscar Laighton, wrote about his childhood on White Island in his book, Ninety Years at the Isles of Shoals:

Many people have said, 'You must have been very lonely at the Light.' They did not know that where our mother dwelt there was happiness also. I am sure no family was ever more united and contented than the Laightons on White Island.

As a young girl, Celia learned to help her father light the lamps and polish the reflectors and lantern glass. The Laightons eventually moved to the much larger island of Appledore, where they operated a hotel for many years. The hotel's guests included Longfellow, Emerson, and Whittier. Levi Thaxter tutored the Laighton children; he and Celia eventually married.

Celia's brother, Oscar Laighton, wrote about his childhood on White Island in his book, Ninety Years at the Isles of Shoals:

Many people have said, 'You must have been very lonely at the Light.' They did not know that where our mother dwelt there was happiness also. I am sure no family was ever more united and contented than the Laightons on White Island.

As a young girl, Celia learned to help her father light the lamps and polish the reflectors and lantern glass. The Laightons eventually moved to the much larger island of Appledore, where they operated a hotel for many years. The hotel's guests included Longfellow, Emerson, and Whittier. Levi Thaxter tutored the Laighton children; he and Celia eventually married.

The author Nathaniel Hawthorne visited White Island with Celia Thaxter's husband, Levi Thaxter, on September 9, 1852.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

The keeper at the time was L. H. D. Shepard. Hawthorne's description of the visit appears in his American Note-Books:

Mr. Thaxter rowed me this morning, in his dory, to White Island, on which is the lighthouse. There was scarcely a breath of air, and a perfectly calm sea; an intensely hot sunshine, with a little haze, so that the horizon was indistinct. Here and there sail-boats sleeping on the water, or moving almost imperceptibly over it. The lighthouse island would be difficult of access in a rough sea, the shore being so rocky. On landing, we found the keeper peeling his harvest of onions, which he had gathered prematurely, because the insects were eating them. His little patch of garden seemed to be a strange kind of soil, as like marine mud as anything; but he had a fair crop of marrow squashes, though injured, as he said, by the last storm; and there were cabbages and a few turnips. I recollect no other garden vegetables. The grass grows pretty luxuriantly, and looked very green where there was any soil; but he kept no cow, nor even a pig nor a hen. His house stands close by the garden,--a small stone building, with peaked roof, and whitewashed. The lighthouse stands on a ledge of rock, with a gulley between, and there is a long covered way, triangular in shape, connecting his residence with it. We ascended into the lantern, which is eighty-seven feet high. It is a revolving light, with several great illuminators of copper silvered, and colored lamp-glasses. Looking downward, we had the island displayed as on a chart, with its little bays, its isthmus of shingly beach connecting two parts of the island, and overflowed at high tide; its sunken rocks about it, indicated by the swell, or slightly breaking surf. The keeper of the light-house was formerly a writing-master. He has a sneaking kind of look, and does not bear a very high character among his neighbors. Since he kept the light, he has lost two wives--the first a young creature whom he used to leave alone upon this desolate rock, and the gloom and terror of the situation were probably the cause of her death.

Mr. Thaxter rowed me this morning, in his dory, to White Island, on which is the lighthouse. There was scarcely a breath of air, and a perfectly calm sea; an intensely hot sunshine, with a little haze, so that the horizon was indistinct. Here and there sail-boats sleeping on the water, or moving almost imperceptibly over it. The lighthouse island would be difficult of access in a rough sea, the shore being so rocky. On landing, we found the keeper peeling his harvest of onions, which he had gathered prematurely, because the insects were eating them. His little patch of garden seemed to be a strange kind of soil, as like marine mud as anything; but he had a fair crop of marrow squashes, though injured, as he said, by the last storm; and there were cabbages and a few turnips. I recollect no other garden vegetables. The grass grows pretty luxuriantly, and looked very green where there was any soil; but he kept no cow, nor even a pig nor a hen. His house stands close by the garden,--a small stone building, with peaked roof, and whitewashed. The lighthouse stands on a ledge of rock, with a gulley between, and there is a long covered way, triangular in shape, connecting his residence with it. We ascended into the lantern, which is eighty-seven feet high. It is a revolving light, with several great illuminators of copper silvered, and colored lamp-glasses. Looking downward, we had the island displayed as on a chart, with its little bays, its isthmus of shingly beach connecting two parts of the island, and overflowed at high tide; its sunken rocks about it, indicated by the swell, or slightly breaking surf. The keeper of the light-house was formerly a writing-master. He has a sneaking kind of look, and does not bear a very high character among his neighbors. Since he kept the light, he has lost two wives--the first a young creature whom he used to leave alone upon this desolate rock, and the gloom and terror of the situation were probably the cause of her death.

The second wife, experiencing the same kind of treatment, ran away from him, and returned to her friends. He pretends to be religious, but drinks. About a year ago he attempted to row out alone from Portsmouth. There was a head wind and head tide, and he would have inevitably drifted out to sea, if Mr. Thaxter had not saved him. While we were standing in his garden-patch, I heard a woman's voice inside the dwelling, but know not whose it was.

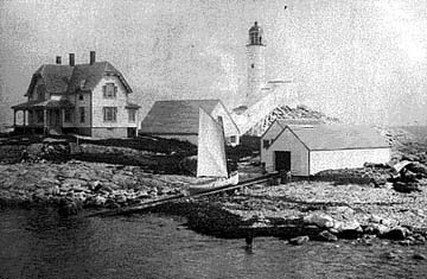

A new 58-foot brick lighthouse tower (left) was built on White Island in 1859. The new tower was fitted with a second-order Fresnel lens.

A duplex keeper's house built in 1878 was removed by the Coast Guard in the 1950s.

There was an amazing rescue at White Island one winter in the mid-1800s. John Bragg Downs was temporarily acting as keeper, with a friend as his assistant. The two men were at the lighthouse when a severe blizzard hit, with blinding snow and heavy seas covering the island. One night, much to their shock, there was a knock at the door.

When they opened the door, the men discovered a lone sailor, dressed in tattered rags and bleeding from many wounds. The man had somehow come ashore from a brig wrecked on the rocks.

A duplex keeper's house built in 1878 was removed by the Coast Guard in the 1950s.

There was an amazing rescue at White Island one winter in the mid-1800s. John Bragg Downs was temporarily acting as keeper, with a friend as his assistant. The two men were at the lighthouse when a severe blizzard hit, with blinding snow and heavy seas covering the island. One night, much to their shock, there was a knock at the door.

When they opened the door, the men discovered a lone sailor, dressed in tattered rags and bleeding from many wounds. The man had somehow come ashore from a brig wrecked on the rocks.

After a great deal of effort, Downs ventured out on a ledge and managed to get a line to the rest of the crew on the vessel. He then tied the line around himself. Downs wedged himself into a crevice, and every man managed to get ashore from the sinking ship.

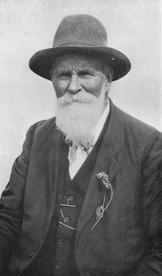

James Burke

The fog bell at White Island was replaced by a new bell and striking machinery in 1906. The bell was replaced later by a powerful air siren.

James Burke, a native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was the keeper from 1894 to 1912. Burke was credited with many rescues during his years at White Island. He once helped 16 women whose pleasure boat had capsized near the island. On another occasion, he saved three persons whose boat was sinking fast. He also rescued four crewmen from the Bangor schooner Medford after they had drifted for four days in an open boat.

Keeper Burke's wife shared some thoughts in a newspaper article in May 1905:

I am feeling much better since the beautiful springtime has come. The mornings are delightful here now, the birds are giving their morning songs, and that seems to put new life into one; while the sun, as it peeps out of the sea so early these fine mornings, seems to bring new strength to go forward to aid life's duties.

James Burke, a native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was the keeper from 1894 to 1912. Burke was credited with many rescues during his years at White Island. He once helped 16 women whose pleasure boat had capsized near the island. On another occasion, he saved three persons whose boat was sinking fast. He also rescued four crewmen from the Bangor schooner Medford after they had drifted for four days in an open boat.

Keeper Burke's wife shared some thoughts in a newspaper article in May 1905:

I am feeling much better since the beautiful springtime has come. The mornings are delightful here now, the birds are giving their morning songs, and that seems to put new life into one; while the sun, as it peeps out of the sea so early these fine mornings, seems to bring new strength to go forward to aid life's duties.

All through the short days of winter I was kept busy, as we had the assistant to board with us, and my daughter Emma, being away this winter, made more steps for me to take. Since that time I have had three men sent by the government to repair what the sea washed to pieces in the heavy storms of winter. The storms were beautiful to watch from the windows, but little [daughter] Lucy was so afraid that she cried with fright, and I kept her in the sitting room, busy cutting out paper dolls, until the storm subsided. Sheets of salt water would strike the windows and sound like the fiercest hailstorm.

During a storm in 1945. Courtesy of Judy Paquette.

Keeper Burke made local newspaper headlines in January 1911 when he kept the light going for six nights through extraordinary circumstances. His wife was ill with pneumonia and the assistant keeper, Gordon Sullivan, was away on shore leave.

Burke fell seriously ill, but he crawled to the lantern on his hands and knees to keep the light going each night.

Burke tried to signal for help, to no avail. When Sullivan returned to the island and found the Burkes in a dire situation, he alerted Captain Joseph Staples of the lifesaving station on Appledore Island. A tugboat was summoned and the Burkes soon received medical attention on the mainland.

After the Coast Guard took over at White Island, three men were assigned to the station. Harold Roberts was one of the crewmen in 1956-58. He later wrote the following:

During the winter of 1956, we were experiencing one of those rare days at the Isles of Shoals when the sun was shining and the sea was placid, but it was still bitter cold.

I decided to take the small double ended peapod dinghy we used to get on and off the island and row around to the back of the island to get close to the seals that often lay on the rocks sunning themselves on such days. This day there was a larger number of seals lying on the rocks and I hoped I could get close to them without arousing them.

Burke fell seriously ill, but he crawled to the lantern on his hands and knees to keep the light going each night.

Burke tried to signal for help, to no avail. When Sullivan returned to the island and found the Burkes in a dire situation, he alerted Captain Joseph Staples of the lifesaving station on Appledore Island. A tugboat was summoned and the Burkes soon received medical attention on the mainland.

After the Coast Guard took over at White Island, three men were assigned to the station. Harold Roberts was one of the crewmen in 1956-58. He later wrote the following:

During the winter of 1956, we were experiencing one of those rare days at the Isles of Shoals when the sun was shining and the sea was placid, but it was still bitter cold.

I decided to take the small double ended peapod dinghy we used to get on and off the island and row around to the back of the island to get close to the seals that often lay on the rocks sunning themselves on such days. This day there was a larger number of seals lying on the rocks and I hoped I could get close to them without arousing them.

As I rowed around the back side of the island about 200 yards out I suddenly heard a roaring noise to my right. A huge wave, a groundswell about 20 feet high, was coming right at me.

I swung the bow of the boat into the wave but not fast enough to prevent the boat from being overturned and me being dumped into the ocean.

The water was bitter cold and I was clothed with heavy foul weather gear including heavy robber boots. The weight of my boots filling with water pulled me down and prevented me from using my legs to kick myself to the surface. Judging from the pressure in my ears I must have sank at least 15 feet before I started slowly rising to the surface. The air trapped in my jacket saved me from being pulled down to the bottom. As soon as I broke surface I started to sink again. My hands were so frozen I could not unclasp the boots that were preventing me from swimming. I knew I was in grave danger of drowning. In desperation and fear called out to God to save me. A moment later, the capsized dingy suddenly appeared right next to me. I was able to hold on to the boat to stay afloat. My next and most immediate problem was the cold. I was freezing to death. I was aware that a man can't stay alive very long exposed to those conditions. The other problem was I was several hundred yards off the island and no one knew I was in trouble. Charlie Martin and I were alone on the island and he was unaware of my predicament.

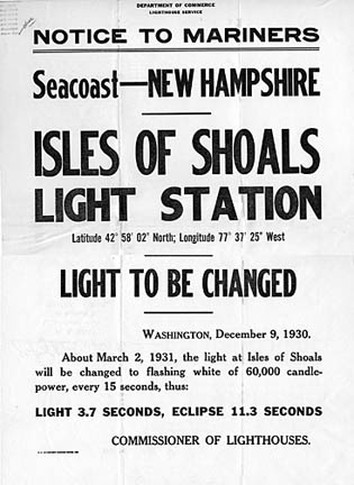

Right: Notice to Mariners concerning a change in the light characteristic in March 1931.

I must have fallen asleep from the cold and was not aware that the boat with me clinging half conscious to the side had drifted to the island and a gentle swell pushed us into the rocks. I had enough strength to climb up out of the water and make my way to the keeper’s house. Charley Martian was in the kitchen when I came in the door. I must have looked frozen, which I was. Charlie got blankets for me to help me recover my body heat. To this day I believe it was divine intervention that saved my life on that bitter cold winter day on the Isles of Shoals.

The water was bitter cold and I was clothed with heavy foul weather gear including heavy robber boots. The weight of my boots filling with water pulled me down and prevented me from using my legs to kick myself to the surface. Judging from the pressure in my ears I must have sank at least 15 feet before I started slowly rising to the surface. The air trapped in my jacket saved me from being pulled down to the bottom. As soon as I broke surface I started to sink again. My hands were so frozen I could not unclasp the boots that were preventing me from swimming. I knew I was in grave danger of drowning. In desperation and fear called out to God to save me. A moment later, the capsized dingy suddenly appeared right next to me. I was able to hold on to the boat to stay afloat. My next and most immediate problem was the cold. I was freezing to death. I was aware that a man can't stay alive very long exposed to those conditions. The other problem was I was several hundred yards off the island and no one knew I was in trouble. Charlie Martin and I were alone on the island and he was unaware of my predicament.

Right: Notice to Mariners concerning a change in the light characteristic in March 1931.

I must have fallen asleep from the cold and was not aware that the boat with me clinging half conscious to the side had drifted to the island and a gentle swell pushed us into the rocks. I had enough strength to climb up out of the water and make my way to the keeper’s house. Charley Martian was in the kitchen when I came in the door. I must have looked frozen, which I was. Charlie got blankets for me to help me recover my body heat. To this day I believe it was divine intervention that saved my life on that bitter cold winter day on the Isles of Shoals.

Kevin Murphy was one of the Coast Guard keepers 1982-83. In an email in August 2009, he wrote, "While I have no horrific storm stories to tell, we certainly had our share of storms and there where times we would get stuck out on the island for a month because we couldn’t get the dory off the island. Occasionally we had to be air lifted off the island which I thought was kind of fun!"

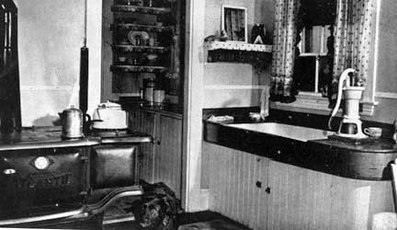

Left: The lighthouse station's kitchen, circa 1950. From The Shoreliner, September 1950.

Murphy said he enjoyed his time on the island and he was happy to see that local people are working for the preservation of the light station's buildings.

Glenn Young of York, Maine, was a machinery technician when he was in the Coast Guard. He was stationed on the island during a memorable storm in March 1984. As 35-foot waves crashed against the lighthouse and keeper's house, the crewmen calmly watched TV.

Douglas Larrabee was the keeper in the early 1950s

About once an hour, Young went to check the light. To do so he had to go through an enclosed wooden walkway between the house and tower. Waves were washing right over the walkway and water was pouring through the cracks, so Young had to wait for the waves to recede before running the length of the walkway. The storm did much damage at the station and deposited a 3 1/2-ton boulder on the helicopter pad.

Rick Bennett and Kevin Madison were among the last Coast Guardsmen at White Island. In the summer, the men would visit the inhabitants of the other islands nearby. Storms sometimes made it very difficult for the crew to land at White Island.

Kevin Madison says that although the 1986 automation of White Island Light was sad in a way, it was also very interesting. The Coast Guard crew spent three months working with a civilian crew from Portland on the automation process.

The huge Fresnel lens was replaced by aerobeacons in the early 1980s. Following the 1986 automation, the Coast Guard keepers were removed. The present VLB-44 LED-type optic is solar-powered.

Hurricane Bob and the ferocious "Perfect Storm" of October 1991 washed away the walkway from the tower to the house, as well as the old fog signal tower.

Rick Bennett and Kevin Madison were among the last Coast Guardsmen at White Island. In the summer, the men would visit the inhabitants of the other islands nearby. Storms sometimes made it very difficult for the crew to land at White Island.

Kevin Madison says that although the 1986 automation of White Island Light was sad in a way, it was also very interesting. The Coast Guard crew spent three months working with a civilian crew from Portland on the automation process.

The huge Fresnel lens was replaced by aerobeacons in the early 1980s. Following the 1986 automation, the Coast Guard keepers were removed. The present VLB-44 LED-type optic is solar-powered.

Hurricane Bob and the ferocious "Perfect Storm" of October 1991 washed away the walkway from the tower to the house, as well as the old fog signal tower.

|

|

This video at left was shot by one of the Coast Guard lighthouse keepers during the blizzard of February 6-7, 1978. It was probably shot from the keeper's house. You can see a storage shed being moved around by the waves that are reaching far up onto the island. Courtesy of Sue Reynolds, The Lighthouse Kids. |

In 1993, White Island became the property of the State of New Hampshire.

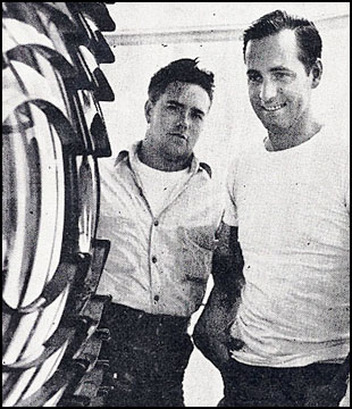

Coast Guard keepers John Parks and Bill Cannon in 1950

The keeper's house has been used in recent years by personnel of the Audubon Society of New Hampshire, who have implemented a tern restoration project on adjacent Seavey Island.

Over the years, the lighthouse tower developed major cracks in its exterior, mostly on the northeast side that bears the brunt of storms.

The good news is that seventh grade students in North Hampton, New Hampshire, along with a teacher, Sue Reynolds, have worked to save the lighthouse. You can see the website of the "Lighthouse Kids" here.

On April 30, 2003, Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire announced that a matching grant of $250,000 in federal funds from the Save America's Treasures program was awarded for the restoration of the White Island Lighthouse.

On June 22, 2005, the Lighthouse Kids presented New Hampshire Governor John Lynch with a check for $110,000. In accepting the check, the state authorized the Division of Parks and Recreation to expend the money for conservation and restoration of the White Island Light Station.

Over the years, the lighthouse tower developed major cracks in its exterior, mostly on the northeast side that bears the brunt of storms.

The good news is that seventh grade students in North Hampton, New Hampshire, along with a teacher, Sue Reynolds, have worked to save the lighthouse. You can see the website of the "Lighthouse Kids" here.

On April 30, 2003, Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire announced that a matching grant of $250,000 in federal funds from the Save America's Treasures program was awarded for the restoration of the White Island Lighthouse.

On June 22, 2005, the Lighthouse Kids presented New Hampshire Governor John Lynch with a check for $110,000. In accepting the check, the state authorized the Division of Parks and Recreation to expend the money for conservation and restoration of the White Island Light Station.

The keeper's house was reroofed and painted, and rotting woodwork was replaced. The renovations stopped water leaks that had plagued the house in recent years.

More than 1,000 bricks were replaced in the tower during the 2005 restoration. The brick courses were strengthened with the addition of stainless steel ties, and the entire tower received a protective layer of stucco. The glass block windows in the tower were replaced by windows that are more like the original ones.

In early 2008, the rotating VRB-25 optic that had been in use at White Island for several years was replaced by a solar-powered VLB-44 light emitting diode unit (LED).

A northeast storm in mid-April 2007 did much damage on the island. The walkway between the house and tower was demolished, and the solar panels for the light were swept away. The walkway was rebuilt using FEMA funds in the summer of 2011.

The Lighthouse Kids started a stewardship program in 2012. Volunteers lived on the island for brief periods during the summer and carried out repairs on the keeper's house and other structures. The first stewards, Marg and John Whedon, had spent 23 years serving as stewards at nearby Smuttynose Island. John Whedon painted the spiral stairs and landings in the lighthouse and cleared out old debris, making the lighthouse more "tour worthy." Marg cleaned debris from the old generator room, improving access to the new walkway that connects the house and tower.

In early 2008, the rotating VRB-25 optic that had been in use at White Island for several years was replaced by a solar-powered VLB-44 light emitting diode unit (LED).

A northeast storm in mid-April 2007 did much damage on the island. The walkway between the house and tower was demolished, and the solar panels for the light were swept away. The walkway was rebuilt using FEMA funds in the summer of 2011.

The Lighthouse Kids started a stewardship program in 2012. Volunteers lived on the island for brief periods during the summer and carried out repairs on the keeper's house and other structures. The first stewards, Marg and John Whedon, had spent 23 years serving as stewards at nearby Smuttynose Island. John Whedon painted the spiral stairs and landings in the lighthouse and cleared out old debris, making the lighthouse more "tour worthy." Marg cleaned debris from the old generator room, improving access to the new walkway that connects the house and tower.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at[email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Clement Jackson (1820-1824); Benjamin Haley (1824-1829); William Godfrey (unofficial assistant hired by Haley, c. 1828-1829); Joseph L. Locke (1829-1839); William Randall (unofficial assistant hired by Locke, c. 1830s?); Asa Caswell(unofficial assistant hired by Locke, c. 1832); Thomas Laighton (1839-1841, 1843-1849); Joseph Cheever (1841-1843); Ben Whaling (employee of Thomas Laighton, c.1839-1849); Fabius Becker (unofficial keeper hired by Thomas Laighton, c.1846-1849); L. H. D. Shepard (1849-1855); Richard G. Haley (1855-1861); Otis F. Haley (assistant, 1859-1861); John Bragg Downs (c. 1850, temporary keeper); Alfred J. Leavitt (1861-1866); Jonathan Godfrey (assistant, 1861-1863); Alonzo D. Berry (assistant, 1863-1864); Albert S. Perkins (assistant, 1864-1866); John E. Hoyt (assistant, 1866-1867); Alonzo Wise (1866-1869); George Balch (assistant, 1867-1868); John L. Allen (assistant, 1867-1868); Wiliam H. White (assistant, 1868-1869); Frank A. Otis (assistant, 1868-1870); Joshua Bickford (1869); Jonathan W. Berry (1869-1874); Abram Mathes (?) (assistant, 1869-1871); Thomas J. Varrell (assistant, 1870); George Chaplin (assistant, 1871); ? Gray (assistant, 1870); ? A. Yeaton (assistant, 1872); Parsons (?) Locke (assistant, 1872-1873); Charles H. Ramsdell (second assistant, 1873); Franklin R. Bragden (assistant, 1874-1876); Israel P. Miller (1874-1876); Edwin J. Hobbs (1876-1880); Alden W. P. White (assistant, 1876-1877, 1880); David R. Grogan (1880-1894); James Burke (1894-1912); Elias Tarlton, Jr. (assistant, 1884-1890); Thomas H. Barber (assistant, 1890-1891); Walter S. Amee (assistant, 1893); John Scannell (assistant, 1893-1894); John A. Hall (assistant, 1894-1896); Wallace S. Chase (assistant, 1897); William M. Brooks (assistant, 1897-1904); Gordon A. Sullivan (assistant, 1909-1912); Alvah Robinson (assistant, c. 1914?); Edwin A. Pettegrow (c. early 1920s); Gleason Colbeth (assistant, c. 1920s); John Olsen (c. 1920s); Albert Staples (1926-1930); James Freeman (assistant, c. 1928-1930); Wilbur Brewster (Coast Guard, c. 1935-1940s); Charles U. Gardner (Coast Guard relief keeper, c, 1942-1943) ; Maxwell A. Deshon (c. 1945); Douglas Larrabee (c. 1945-1950); Bill Cannon (Coast Guard, c. 1948-1950); John Parks (Coast Guard, c, 1948-1950); Charles Martin (c. 1956-1958); Harold Roberts (c. 1956-1958); Anthony Cherico (c. 1956-1958); Allan Petersen (USCG Officer in Charge, 1961-1962); BM1 Ira Machon (Coast Guard Officer in Charge, c. 1965-1966); ? Gordon, USCG (1968-1970); Bruce Blanchard (Coast Guard EN2, 1968-70); Bob Larson (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); Ron Tinkham (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); John C. Waterman (Coast Guard, c. 1977-1978); PO1 Rick Loster, USCG Officer in Charge (8/1983-6/1984); Ed Latta (Coast Guard, 1981-82); FN Kevin Murphy (Coast Guard, 1982-1983); PO3 Joel Wood (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Jeff Jones, (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Scott Powell, (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Glenn Young (Coast Guard, c. 1984); Rick Bennett, (Coast Guard, c. 1986); Kevin Madison, (Coast Guard, c. 1986)

Clement Jackson (1820-1824); Benjamin Haley (1824-1829); William Godfrey (unofficial assistant hired by Haley, c. 1828-1829); Joseph L. Locke (1829-1839); William Randall (unofficial assistant hired by Locke, c. 1830s?); Asa Caswell(unofficial assistant hired by Locke, c. 1832); Thomas Laighton (1839-1841, 1843-1849); Joseph Cheever (1841-1843); Ben Whaling (employee of Thomas Laighton, c.1839-1849); Fabius Becker (unofficial keeper hired by Thomas Laighton, c.1846-1849); L. H. D. Shepard (1849-1855); Richard G. Haley (1855-1861); Otis F. Haley (assistant, 1859-1861); John Bragg Downs (c. 1850, temporary keeper); Alfred J. Leavitt (1861-1866); Jonathan Godfrey (assistant, 1861-1863); Alonzo D. Berry (assistant, 1863-1864); Albert S. Perkins (assistant, 1864-1866); John E. Hoyt (assistant, 1866-1867); Alonzo Wise (1866-1869); George Balch (assistant, 1867-1868); John L. Allen (assistant, 1867-1868); Wiliam H. White (assistant, 1868-1869); Frank A. Otis (assistant, 1868-1870); Joshua Bickford (1869); Jonathan W. Berry (1869-1874); Abram Mathes (?) (assistant, 1869-1871); Thomas J. Varrell (assistant, 1870); George Chaplin (assistant, 1871); ? Gray (assistant, 1870); ? A. Yeaton (assistant, 1872); Parsons (?) Locke (assistant, 1872-1873); Charles H. Ramsdell (second assistant, 1873); Franklin R. Bragden (assistant, 1874-1876); Israel P. Miller (1874-1876); Edwin J. Hobbs (1876-1880); Alden W. P. White (assistant, 1876-1877, 1880); David R. Grogan (1880-1894); James Burke (1894-1912); Elias Tarlton, Jr. (assistant, 1884-1890); Thomas H. Barber (assistant, 1890-1891); Walter S. Amee (assistant, 1893); John Scannell (assistant, 1893-1894); John A. Hall (assistant, 1894-1896); Wallace S. Chase (assistant, 1897); William M. Brooks (assistant, 1897-1904); Gordon A. Sullivan (assistant, 1909-1912); Alvah Robinson (assistant, c. 1914?); Edwin A. Pettegrow (c. early 1920s); Gleason Colbeth (assistant, c. 1920s); John Olsen (c. 1920s); Albert Staples (1926-1930); James Freeman (assistant, c. 1928-1930); Wilbur Brewster (Coast Guard, c. 1935-1940s); Charles U. Gardner (Coast Guard relief keeper, c, 1942-1943) ; Maxwell A. Deshon (c. 1945); Douglas Larrabee (c. 1945-1950); Bill Cannon (Coast Guard, c. 1948-1950); John Parks (Coast Guard, c, 1948-1950); Charles Martin (c. 1956-1958); Harold Roberts (c. 1956-1958); Anthony Cherico (c. 1956-1958); Allan Petersen (USCG Officer in Charge, 1961-1962); BM1 Ira Machon (Coast Guard Officer in Charge, c. 1965-1966); ? Gordon, USCG (1968-1970); Bruce Blanchard (Coast Guard EN2, 1968-70); Bob Larson (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); Ron Tinkham (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); John C. Waterman (Coast Guard, c. 1977-1978); PO1 Rick Loster, USCG Officer in Charge (8/1983-6/1984); Ed Latta (Coast Guard, 1981-82); FN Kevin Murphy (Coast Guard, 1982-1983); PO3 Joel Wood (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Jeff Jones, (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Scott Powell, (Coast Guard, c. 1983); Glenn Young (Coast Guard, c. 1984); Rick Bennett, (Coast Guard, c. 1986); Kevin Madison, (Coast Guard, c. 1986)