History of Cape Elizabeth Light, Cape Elizabeth, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Postcards

Click here for a gallery of Cape Elizabeth Light photos at Smugmug (prints and gift items available)

The Two Lights of Cape Elizabeth stand up at the end of a long and narrow granite ridge raised fifty or sixty feet above the low ground around it. ...The outlook opened to us here, whether of sea or shore, of windy cape or tumbling surf, is uncommonly fine, if only one could get rid of the train of ideas that these roaring reefs on one hand, and the life-saving station on the other ...so infallibly suggest. Even in the season of calm seas and serene skies these gray little cabins by the sea constantly remind us of lurking dangers... -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

After English explorer Captain John Smith sailed along the coast of New England in 1614, a prominent cape in what is now southern Maine was named after Princess Elizabeth, sister of Charles I. Two-hundred-acre Richmond Island, a short distance off Cape Elizabeth to the south, was the site of the earliest European settlement in this part of Maine, beginning in 1628. The settlement that later developed on the cape was, for many years, part of the town of Falmouth.

Cape Elizabeth was incorporated as a separate town in 1765. In 1895, the northern half of the town was incorporated as South Portland. It was the development of Portland Harbor, along the north side of the cape on the Fore River, that led to the need for better aids to navigation in the vicinity. The harbor rebounded after the Revolution to become the most important seaport in the state.

The approach to Portland Harbor from the south was treacherous, and as maritime trade increased, so did shipwrecks. One of the most heart-rending near Cape Elizabeth was the July 12, 1807, wreck of the schooner Charles, which was dashed to pieces on a reef in fog and heavy seas. At least 16 men and women died in the disaster.

A 50-foot stone black and white pyramidal stone day beacon was erected in 1811 on a rocky promontory at the southeastern point of Cape Elizabeth, at the southwestern limit of Casco Bay and about five miles southeast of Portland Harbor. The beacon was completed by the end of November by the contractors Edward Robinson and John F. Bartlett.

Cape Elizabeth was incorporated as a separate town in 1765. In 1895, the northern half of the town was incorporated as South Portland. It was the development of Portland Harbor, along the north side of the cape on the Fore River, that led to the need for better aids to navigation in the vicinity. The harbor rebounded after the Revolution to become the most important seaport in the state.

The approach to Portland Harbor from the south was treacherous, and as maritime trade increased, so did shipwrecks. One of the most heart-rending near Cape Elizabeth was the July 12, 1807, wreck of the schooner Charles, which was dashed to pieces on a reef in fog and heavy seas. At least 16 men and women died in the disaster.

A 50-foot stone black and white pyramidal stone day beacon was erected in 1811 on a rocky promontory at the southeastern point of Cape Elizabeth, at the southwestern limit of Casco Bay and about five miles southeast of Portland Harbor. The beacon was completed by the end of November by the contractors Edward Robinson and John F. Bartlett.

A sum of $4,500 was appropriated for a light station at Cape Elizabeth in February 1828. It was determined that the station would have two lights, one fixed and one revolving, to differentiate it from Wood Island Light (revolving) to the south, and from Portland Head Light (fixed) to the north.

The stone marker was torn down to make way for the first pair of Cape Elizabeth lighthouses, built by the mason Jeremiah Berry for $4,250. The east light was built on the former site of the marker, and the inner or west light was built directly to the west, 895 feet away.

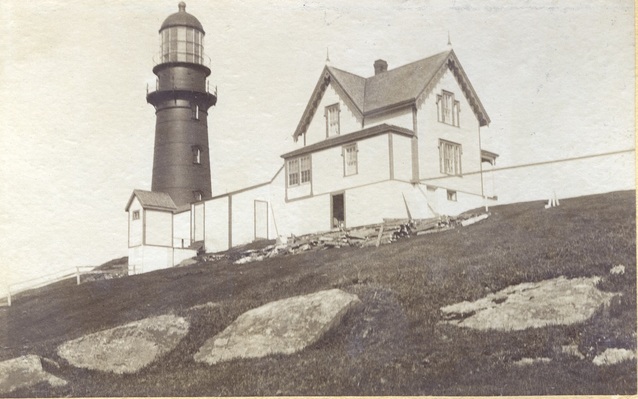

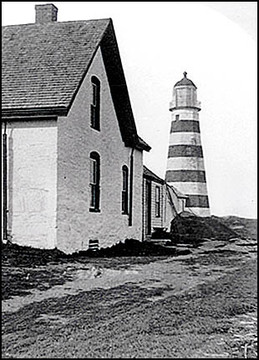

Right: Circa 1859 view of the east tower and keeper's house. (National Archives)

Elisha Jordan was appointed first keeper at a salary of $450 per year. He remained for six years. Jordan was instructed that he had to “reside at the station and make it a habit to be at home.”

Both 65-foot towers (to the tops of the lanterns) were octagonal and built of rubblestone, with octagonal wrought-iron lanterns. The east tower had 15 lamps with 16-inch reflectors, showing a fixed white light 129 feet above mean high water. The west tower had 14 lamps with 14-inch reflectors; the apparatus revolved to produce a flashing light, 132 feet above mean high water.

Right: Circa 1859 view of the east tower and keeper's house. (National Archives)

Elisha Jordan was appointed first keeper at a salary of $450 per year. He remained for six years. Jordan was instructed that he had to “reside at the station and make it a habit to be at home.”

Both 65-foot towers (to the tops of the lanterns) were octagonal and built of rubblestone, with octagonal wrought-iron lanterns. The east tower had 15 lamps with 16-inch reflectors, showing a fixed white light 129 feet above mean high water. The west tower had 14 lamps with 14-inch reflectors; the apparatus revolved to produce a flashing light, 132 feet above mean high water.

The lights were in service by the end of October 1828. The lights were considered among the most important on the coast; mariners approaching Portland Harbor would line them up to know they were on course.

In his 1843 report to Congress, the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis was very critical of the construction of the towers. Lewis also reported additionally that the fog bell could not be heard above the roar of the surf. George Fickett, who had been keeper since 1841 at a yearly salary of $500, complained that the great distance between the two towers made his work arduous, especially when snow filled the valley between them.

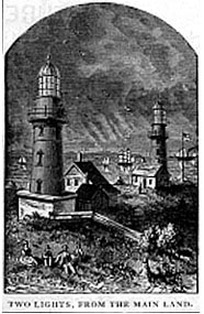

Left: Circa 1859 view of the west tower. (National Archives)

Hiram Staples followed Fickett as keeper in 1844. During his tenure in 1847, it was recorded that the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who lived in Portland, visited the station and climbed the west tower.

William Jordan, who became principal keeper in 1849, complained of the lack of assistants in an 1852 letter. “I have to hire a boy during the summer season,” he wrote, “and a man during the winter months, and, if I did not do so, could not faithfully keep things in order.” The yearly salary of the keeper was still $500; Jordan asked for a raise of $100 to cover the expense of hiring extra help. Nathan Davis succeeded Jordan as keeper in 1853, and Davis was provided an assistant at $200 yearly. A second assistant was added a few years later.

Left: Circa 1859 view of the west tower. (National Archives)

Hiram Staples followed Fickett as keeper in 1844. During his tenure in 1847, it was recorded that the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who lived in Portland, visited the station and climbed the west tower.

William Jordan, who became principal keeper in 1849, complained of the lack of assistants in an 1852 letter. “I have to hire a boy during the summer season,” he wrote, “and a man during the winter months, and, if I did not do so, could not faithfully keep things in order.” The yearly salary of the keeper was still $500; Jordan asked for a raise of $100 to cover the expense of hiring extra help. Nathan Davis succeeded Jordan as keeper in 1853, and Davis was provided an assistant at $200 yearly. A second assistant was added a few years later.

In 1853, J. B. Coyle of the Portland Steam Packet Company complained that the fog bell was “entirely too small for one occupying so important position.”

At a cost of $2,500, a larger bell and new striking machinery were installed in the following year. By the end of 1854, the towers got new cast-iron stairways, and both were lined with brick. Fresnel lenses were installed in the towers around the same time, replacing the old multiple lamps and reflectors.

In the summer of 1855, it was announced that the west light was to be discontinued, and the characteristic of the east light would be changed to occulting. Despite protests, the change went into effect on August 1, 1855. Under this arrangement, the single revolving light was often hard to distinguish from Wood Island Light to the south.

On April 1, 1856, the two lights were returned to their former condition, and the light at Wood Island was changed from white to red to eliminate any chance of confusion.

Right: The 1828 east lighthouse after 1865, when it was painted with red bands. Courtesy of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

During the Civil War, Asbury Staples, the assistant keeper in charge of the west light, enlisted in the Second Maine Battery Light Artillery. His father, Michael Staples, who was also an assistant keeper, requested that his other children be officially appointed as assistants. His teenaged daughter Amelia and her younger brother, Charles, became responsible for keeping the light and related equipment. Amelia and Charles assisted in the grim task of draping the towers in black at the news of President Lincoln’s assassination.

The lights were repainted in 1865 in an effort to make them easier to recognize in daylight. The west tower received one large vertical red stripe, while the east tower was painted with four horizontal red bands.

The Lighthouse Board announced that a steam fog whistle with a powerful eight-second blast was installed in 1869, with and a new building was constructed to house the equipment. Two more assistant keepers were assigned to the station at this time. A more powerful fog whistle was installed by 1876.

In the summer of 1855, it was announced that the west light was to be discontinued, and the characteristic of the east light would be changed to occulting. Despite protests, the change went into effect on August 1, 1855. Under this arrangement, the single revolving light was often hard to distinguish from Wood Island Light to the south.

On April 1, 1856, the two lights were returned to their former condition, and the light at Wood Island was changed from white to red to eliminate any chance of confusion.

Right: The 1828 east lighthouse after 1865, when it was painted with red bands. Courtesy of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

During the Civil War, Asbury Staples, the assistant keeper in charge of the west light, enlisted in the Second Maine Battery Light Artillery. His father, Michael Staples, who was also an assistant keeper, requested that his other children be officially appointed as assistants. His teenaged daughter Amelia and her younger brother, Charles, became responsible for keeping the light and related equipment. Amelia and Charles assisted in the grim task of draping the towers in black at the news of President Lincoln’s assassination.

The lights were repainted in 1865 in an effort to make them easier to recognize in daylight. The west tower received one large vertical red stripe, while the east tower was painted with four horizontal red bands.

The Lighthouse Board announced that a steam fog whistle with a powerful eight-second blast was installed in 1869, with and a new building was constructed to house the equipment. Two more assistant keepers were assigned to the station at this time. A more powerful fog whistle was installed by 1876.

A larger brick fog signal building, 32 by 32 feet, was constructed in 1886. The fog signal was in operation for 1,117 hours in 1888, which consumed 71,500 pounds of coal.

Fog signal building, circa early 1900s. (National Archives)

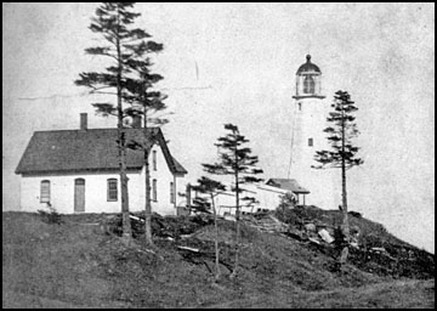

In 1872, the Lighthouse Board announced that the two towers had deteriorated to the point that they had to be rebuilt. A pair of identical 67-foot cast-iron towers replaced the original towers in 1874, after a congressional appropriation of $30,000. The cast-iron segments of the towers were manufactured at the Portland Machine Works.

The lighthouses were given delicate Italianate architectural detailing. Second-order Fresnel lenses were installed in both towers. A new wood-frame, one-and-one-half-story dwelling was built for the principal keeper near the east tower in 1878.

The west light was discontinued again in 1882; again it was relighted after complaints that the remaining light was too easily confused with Wood Island Light to the south. The towers were painted brown during two separate periods; they have been white since 1902.

The lighthouses were given delicate Italianate architectural detailing. Second-order Fresnel lenses were installed in both towers. A new wood-frame, one-and-one-half-story dwelling was built for the principal keeper near the east tower in 1878.

The west light was discontinued again in 1882; again it was relighted after complaints that the remaining light was too easily confused with Wood Island Light to the south. The towers were painted brown during two separate periods; they have been white since 1902.

Marcus Aurelius Hanna, a Medal of Honor winner for bravery in the Civil War, was keeper in 1885 during one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of the light station.

On the night of January 28, Hanna was suffering from a bad cold. A storm hit and increased in severity as the night progressed.

Hanna sounded the steam fog whistle all night despite being ill and exhausted. Assistant Keeper Hiram Staples relieved Hanna at 6:00 a.m. The blizzard was by then "one of the coldest and most violent storms of snow, wind and vapor... that I ever witnessed," Hanna later said. The keeper had to crawl through enormous snowdrifts back to the house.

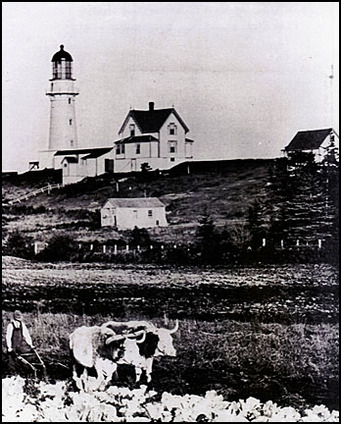

Right: Early 1900s view of the 1874 east lighthouse. Courtesy of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

Hanna was soon asleep. His wife extinguished the lights in both towers after sunrise. Then, at 8:40 a.m., his wife, Louisianna, looked out toward the ocean and saw a schooner aground on Dyer's Ledge near the fog signal building. The vessel was the Australia out of Boothbay. The schooner had been headed for Boston with a cargo of ice from the Kennebec River in the hold and 150 barrels of mackerel on deck. The captain had already been swept away by the waves; only two crew members remained alive. The men had climbed to the rigging and were practically frozen alive in the bitter cold.

Louisianna Hanna shouted to her husband, "There is a vessel ashore near the fog signal!" Hanna rushed to the signal house. Amazingly, Assistant Keeper Staples hadn't seen the wreck through the thick snow. Hanna and Staples hurried to the edge of the water near the schooner.

Hanna sounded the steam fog whistle all night despite being ill and exhausted. Assistant Keeper Hiram Staples relieved Hanna at 6:00 a.m. The blizzard was by then "one of the coldest and most violent storms of snow, wind and vapor... that I ever witnessed," Hanna later said. The keeper had to crawl through enormous snowdrifts back to the house.

Right: Early 1900s view of the 1874 east lighthouse. Courtesy of the American Lighthouse Foundation.

Hanna was soon asleep. His wife extinguished the lights in both towers after sunrise. Then, at 8:40 a.m., his wife, Louisianna, looked out toward the ocean and saw a schooner aground on Dyer's Ledge near the fog signal building. The vessel was the Australia out of Boothbay. The schooner had been headed for Boston with a cargo of ice from the Kennebec River in the hold and 150 barrels of mackerel on deck. The captain had already been swept away by the waves; only two crew members remained alive. The men had climbed to the rigging and were practically frozen alive in the bitter cold.

Louisianna Hanna shouted to her husband, "There is a vessel ashore near the fog signal!" Hanna rushed to the signal house. Amazingly, Assistant Keeper Staples hadn't seen the wreck through the thick snow. Hanna and Staples hurried to the edge of the water near the schooner.

The keeper said later, "I felt a terrible responsibility thrust upon me, and I resolved to attempt the rescue at any hazard."

Marcus Hanna (U.S. Coast Guard photo)

Hanna tried a number of times to throw a line with an iron weight at its end to the vessel but failed. Feeling the situation was hopeless, Staples returned to the fog signal building. Meanwhile, Hanna's wife alerted neighbors.

Hanna, practically frozen by this time, waded waist-deep into the ocean and again threw the line to the schooner, this time hitting his target. Crewman Irving Pierce managed to pull himself from the rigging and tied the line around himself. Hanna somehow pulled the helpless man through the waves and over the rocks to the shore. According to Hanna, "Pierce's jaws were set; he was totally blind from exposure to the cold, and the expression of his face I shall not soon forget."

After several tries, Hanna landed the line on the Australia again. The other crewman, William Kellar, tied the rope around himself. Hanna's strength was giving out and he faltered as he tried to pull the man to safety. Just then, Assistant Keeper Staples and two neighbors arrived. The four men hauled Kellar to the shore, then carried the two sailors to the fog signal building.

The men were given dry clothes and, once they had thawed enough, hot food and drink. After two days they had recovered enough to be taken to Portland by sled.

Hanna, practically frozen by this time, waded waist-deep into the ocean and again threw the line to the schooner, this time hitting his target. Crewman Irving Pierce managed to pull himself from the rigging and tied the line around himself. Hanna somehow pulled the helpless man through the waves and over the rocks to the shore. According to Hanna, "Pierce's jaws were set; he was totally blind from exposure to the cold, and the expression of his face I shall not soon forget."

After several tries, Hanna landed the line on the Australia again. The other crewman, William Kellar, tied the rope around himself. Hanna's strength was giving out and he faltered as he tried to pull the man to safety. Just then, Assistant Keeper Staples and two neighbors arrived. The four men hauled Kellar to the shore, then carried the two sailors to the fog signal building.

The men were given dry clothes and, once they had thawed enough, hot food and drink. After two days they had recovered enough to be taken to Portland by sled.

Six months later, Marcus Hanna received a gold lifesaving medal for "heroism involving great peril to his life," after what has to rank as one of the greatest lifesaving feats at an American lighthouse.

In August 1997, the Coast Guard launched a new $12.5 million 175-foot buoy tender (right) named the Marcus Hanna. A replica of Hanna's lifesaving medal is mounted on board. The cutter's home port is South Portland, Maine.

The Hannas left in 1888, and Leander White of New Castle, New Hampshire, became the new principal keeper. White stayed until 1909, when he became the keeper at Portsmouth Harbor Light Station in New Hampshire. When he left Cape Elizabeth, a newspaper called Coast Watch reported:, “Capt. White is the fourth oldest keeper in point of service in this district, having served 37 years in the lighthouse dept. He is one of the best men in this dept. of the government.”

In 1890, the old stone dwelling occupied by the second assistant keeper was torn down, and a new wood-frame dwelling was constructed.

The Hannas left in 1888, and Leander White of New Castle, New Hampshire, became the new principal keeper. White stayed until 1909, when he became the keeper at Portsmouth Harbor Light Station in New Hampshire. When he left Cape Elizabeth, a newspaper called Coast Watch reported:, “Capt. White is the fourth oldest keeper in point of service in this district, having served 37 years in the lighthouse dept. He is one of the best men in this dept. of the government.”

In 1890, the old stone dwelling occupied by the second assistant keeper was torn down, and a new wood-frame dwelling was constructed.

The Lighthouse Board announced in 1891 that four families were living in three houses, with two dwellings near the east tower and one near the west tower. A fourth dwelling, said the board, was urgently needed. No action was taken until 1901, when the dwelling residence at the west tower was enlarged and improved.

In October 1911, one of the keepers, William P. Richardson, was fishing in one of the station's rowboats. Increasingly heavy seas swept the boat into the rocks and broke it apart. Richardson was thrown into the waves and began to swim for shore, a few hundred feet away. Crewmen at the nearby lifesaving station spotted Richardson and swiftly launched a surfboat. They pulled the keeper from the cold sea and got him safely to shore.

Left: Leander White was keeper 1888-1909. Courtesy of Chuck Petlick.

During World War I, military personnel patrolled the grounds around the station. One of the assistant keepers at the time was James Anderson, and his daughter, Edwina Davis, later recalled that the soldiers swept off a pond so the lighthouse families could ice skate. Edwina and the other lighthouse children walked four miles each way to school each every day, as there was no other way for them to get there.

Left: Leander White was keeper 1888-1909. Courtesy of Chuck Petlick.

During World War I, military personnel patrolled the grounds around the station. One of the assistant keepers at the time was James Anderson, and his daughter, Edwina Davis, later recalled that the soldiers swept off a pond so the lighthouse families could ice skate. Edwina and the other lighthouse children walked four miles each way to school each every day, as there was no other way for them to get there.

In 1924, the government decided to change all twin light stations to single lights. The west light was extinguished for good.

On December 20, 1925, the east light was electrified and increased to 500,000 candlepower, which at the time made it the second most powerful light in New England (after Highland Light on Cape Cod).

During World War II, the lantern was removed from the discontinued west light and the tower was converted into an observation post.

Right: Joseph Upton, courtesy of the Cape Elizabeth Historical Preservation Society.

In 1934, Keeper Joseph H. Upton, 65 years old, went to the tower to light an auxiliary light in place of the main light, which had failed. About 11:30 p.m., his wife went to the tower and found Upton unconscious at the bottom of the stairs.

A fall down the stairs had fractured his skull, and he died in a hospital a short time later. Upton had previously been keeper at White Island Light and assistant keeper at Matinicus Rock.

During World War II, the lantern was removed from the discontinued west light and the tower was converted into an observation post.

Right: Joseph Upton, courtesy of the Cape Elizabeth Historical Preservation Society.

In 1934, Keeper Joseph H. Upton, 65 years old, went to the tower to light an auxiliary light in place of the main light, which had failed. About 11:30 p.m., his wife went to the tower and found Upton unconscious at the bottom of the stairs.

A fall down the stairs had fractured his skull, and he died in a hospital a short time later. Upton had previously been keeper at White Island Light and assistant keeper at Matinicus Rock.

The last civilian keeper at Cape Elizabeth was Edward Elliot. During World War II, Elliot was ordered to extinguish the light during a coastal blackout. The keeper also owned a nearby cottage that he rented to a woman who often complained about the lighthouse beam disturbing her sleep.

The night he was ordered to turn off the light, Elliot visited the woman and told her he had decided to turn it off so she could sleep better. It wasn't until she read the newspaper that the tenant realized Elliot had been joking.

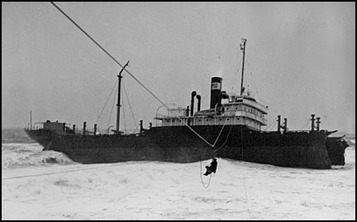

Another famous wreck near Two Lights was the coal collier Oakey L. Alexander in 1947. The vessel broke in two eight miles from Cape Elizabeth in a March gale. The stern half, with 32 crew members aboard, drifted onto the rocks near the lighthouse station.

Left: The rescue of the men aboard the Oakey Alexander by breeches buoy. Courtesy of the Museum at Portland Head Light.

Earle Drinkwater and his crew at the nearby Cape Elizabeth Lifeboat Station, with help from other Coast Guardsmen and local fishermen, rescued the entire crew by breeches buoy. The wrecked Alexander remained just offshore at Cape Elizabeth for years and was viewed by countless sightseers.

Personnel from the Cape Elizabeth Lifeboat Station cared for the navigation equipment until the light's automation in 1963. Dave Mason, whose father John Mason was the officer in charge circa 1952 to 1957 and 1959 to 1962, wrote the following in December 2012:

I have many fond memories of playing at the lifeboat station, fishing for flounder with my grandfather in a Coast Guard rowboat in the cove, picking blueberries and blackberries on the hill with my mom and grandmother and catching dozens of garter snakes that seemed to be everywhere in those days. . . The Coast Guard was a huge part of my childhood and my father's service was a source of immense pride for him.

Another famous wreck near Two Lights was the coal collier Oakey L. Alexander in 1947. The vessel broke in two eight miles from Cape Elizabeth in a March gale. The stern half, with 32 crew members aboard, drifted onto the rocks near the lighthouse station.

Left: The rescue of the men aboard the Oakey Alexander by breeches buoy. Courtesy of the Museum at Portland Head Light.

Earle Drinkwater and his crew at the nearby Cape Elizabeth Lifeboat Station, with help from other Coast Guardsmen and local fishermen, rescued the entire crew by breeches buoy. The wrecked Alexander remained just offshore at Cape Elizabeth for years and was viewed by countless sightseers.

Personnel from the Cape Elizabeth Lifeboat Station cared for the navigation equipment until the light's automation in 1963. Dave Mason, whose father John Mason was the officer in charge circa 1952 to 1957 and 1959 to 1962, wrote the following in December 2012:

I have many fond memories of playing at the lifeboat station, fishing for flounder with my grandfather in a Coast Guard rowboat in the cove, picking blueberries and blackberries on the hill with my mom and grandmother and catching dozens of garter snakes that seemed to be everywhere in those days. . . The Coast Guard was a huge part of my childhood and my father's service was a source of immense pride for him.

The 1878 Victorian principal keeper's house is now privately owned. An assistant keeper's house was incorporated into a new home, and another assistant keeper's house was torn down.

The west tower

After its military use in World War II, the west tower passed into private ownership. It was sold to the highest bidder in 1959 along with several buildings and 10.5 acres of land. In 1971, it was purchased by actor Gary Merrill (Bette Davis' ex-husband) for $28,000.

During his time at Cape Elizabeth, Merrill was regarded as an eccentric. Among other things, he gained attention by putting a donkey in the back of his Cadillac convertible and driving through town. He later ran unsuccessfully for the Maine state legislature. The west light was sold twice in the 1980s.

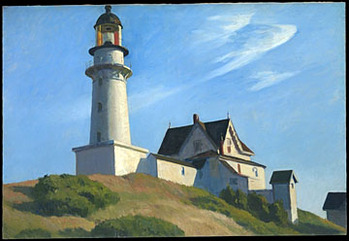

Cape Elizabeth Light was immortalized in a few of Edward Hopper's paintings in the 1920s, one of which was reproduced on a 1970 postage stamp (below right) commemorating the 150th anniversary of Maine's statehood.

During his time at Cape Elizabeth, Merrill was regarded as an eccentric. Among other things, he gained attention by putting a donkey in the back of his Cadillac convertible and driving through town. He later ran unsuccessfully for the Maine state legislature. The west light was sold twice in the 1980s.

Cape Elizabeth Light was immortalized in a few of Edward Hopper's paintings in the 1920s, one of which was reproduced on a 1970 postage stamp (below right) commemorating the 150th anniversary of Maine's statehood.

The east light circa late 1980s, when the second-order Fresnel lens was still in service.

The light was automated in 1963, and the 1,800-pound second-order Fresnel lens was removed in the mid-1990s.

It was the last lens floating on a mercury bath in use in New England. The lens (left) was on display at Cape Elizabeth Town Hall until July 2013. The lens is valued at $2.5 million.

The lens is now the centerpiece of an exhibit at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath (left).

The exhibit opened in June 2017.

The lens is now the centerpiece of an exhibit at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath (left).

The exhibit opened in June 2017.

|

In 1998, William Kourakos, owner of the keeper's house by the east light, announced that he planned to tear down some additions made to the house in 1979, then enlarge the house and add a built-in garage.

The house today is a vastly changed dwelling from the one that was immortalized by Edward Hopper. |

In May 2000, this historic treasure was licensed by the Coast Guard to the American Lighthouse Foundation.

Cape Elizabeth Light, one of the most handsome cast-iron lighthouses in New England, remains an active aid to navigation, and the optic and related equipment are still maintained by the Coast Guard. The grounds immediately around the lighthouse are not open to the public.

In the fall of 2008, the American Lighthouse Foundation contracted Leslie Masonry to carry out repairs on the lighthouse foundation. Click here for details.

Left: Jim Leslie, Ken Morse and Jake Johnson remove wooden forms from the east side of the concrete base. Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.

Below: Some views inside the east light.

In the fall of 2008, the American Lighthouse Foundation contracted Leslie Masonry to carry out repairs on the lighthouse foundation. Click here for details.

Left: Jim Leslie, Ken Morse and Jake Johnson remove wooden forms from the east side of the concrete base. Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.

Below: Some views inside the east light.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Elijah Jordan (1828-1834); Charles Staples (1834-1835); George Fickett (1841-1844); Hiram Staples (1844-1849); William Jordan (1849-1853); Ivory Jordan (1853); Nathan Davis (1853-1859); James Tolman Hanna (assistant, 1853-1876); Milton Sibby (1859-1861); J. Mariner (1861-1869); Enoch Dyer (1869-1872); Hezekiah Long (1872-1873); Michael Staples (assistant, c.1860s); Asbury Staples (assistant, c. 1860s); Louise A. Hanna (third assistant (1874-?); William Henry Hanna (assistant, c. 1873-1876); Harry S. Libby (first assistant, 1876-1881); Joseph W. Girty (second assistant, 1878-1880); Charles E. Chase (second assistant, 1880); Albert R. Angell (second assistant, 1880-1881, first assistant 1881-c.1900); Hiram Staples (second assistant (1881-1886); William G. Williams (second assistant, 1886); Fernando Wallace (second assistant, 1886); Marcus A. Hanna (1873-1888); Leander White (1888-1909); Henry M. Cuskley (assistant, 1897-1903); John W. Cameron (third assistant, c. early 1900s); Arnold B. White (third assistant, 1904-1909); J. M. Austin (assistant, c. early 1900s); William P. Richardson (c. 1911); James Anderson (assistant, 1917-?); Augustus "Gus" Wilson (assistant, 1917); Frank Lewis Cotton (assistant ?-1909, principal keeper 1909-1926); Robert Thayer Sterling (assistant, somewhere between 1915 and 1928); Joseph H. Upton (1926-1934, died in service); Edward D. Elliot (or Elliott) (? - 1946); William Woodward (1946-1947); Everett Lincoln Marston (Coast Guard assistant ?-1947)

Between 1947 and the automation of the light in 1960, Coast Guard personnel from the Two Lights station cared for the light. Some of the personnel during that period were: John Mason (Coast Guard officer in charge, 1952-1953, 1953-1957, and 1959-1962); Clifton Morong (1946-1955); Joseph Bakken (c. 1953)

Elijah Jordan (1828-1834); Charles Staples (1834-1835); George Fickett (1841-1844); Hiram Staples (1844-1849); William Jordan (1849-1853); Ivory Jordan (1853); Nathan Davis (1853-1859); James Tolman Hanna (assistant, 1853-1876); Milton Sibby (1859-1861); J. Mariner (1861-1869); Enoch Dyer (1869-1872); Hezekiah Long (1872-1873); Michael Staples (assistant, c.1860s); Asbury Staples (assistant, c. 1860s); Louise A. Hanna (third assistant (1874-?); William Henry Hanna (assistant, c. 1873-1876); Harry S. Libby (first assistant, 1876-1881); Joseph W. Girty (second assistant, 1878-1880); Charles E. Chase (second assistant, 1880); Albert R. Angell (second assistant, 1880-1881, first assistant 1881-c.1900); Hiram Staples (second assistant (1881-1886); William G. Williams (second assistant, 1886); Fernando Wallace (second assistant, 1886); Marcus A. Hanna (1873-1888); Leander White (1888-1909); Henry M. Cuskley (assistant, 1897-1903); John W. Cameron (third assistant, c. early 1900s); Arnold B. White (third assistant, 1904-1909); J. M. Austin (assistant, c. early 1900s); William P. Richardson (c. 1911); James Anderson (assistant, 1917-?); Augustus "Gus" Wilson (assistant, 1917); Frank Lewis Cotton (assistant ?-1909, principal keeper 1909-1926); Robert Thayer Sterling (assistant, somewhere between 1915 and 1928); Joseph H. Upton (1926-1934, died in service); Edward D. Elliot (or Elliott) (? - 1946); William Woodward (1946-1947); Everett Lincoln Marston (Coast Guard assistant ?-1947)

Between 1947 and the automation of the light in 1960, Coast Guard personnel from the Two Lights station cared for the light. Some of the personnel during that period were: John Mason (Coast Guard officer in charge, 1952-1953, 1953-1957, and 1959-1962); Clifton Morong (1946-1955); Joseph Bakken (c. 1953)