History of Plymouth Light, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

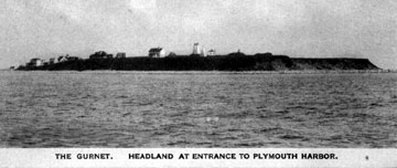

The seven-mile long, 27-acre peninsula known as the Gurnet is at the northern border of Plymouth Bay. The name "Gurnet" apparently came from similar areas in England, which were named for the abundant fish of the same name.

Plymouth developed a significant fishing industry, with 75 fishing vessels by the 1770s. Coastal and foreign trade based in Plymouth helped make it one of the major ports of colonial America, and nearby Duxbury and Kingston also became important centers for trade and shipbuilding. The local maritime traffic necessitated a navigational aid at the Gurnet.

The first lighthouse on the high bluff at the eastern end of the Gurnet was authorized by an act of the colonial legislature on February 17, 1768.

The structure, built for 660 pounds, took the form of a wooden dwelling with a lantern at each end of its roof, which made this the site of North America's first "twin lights."

The lights were in operation by September 1768. The station was built on land owned by John and Hannah Thomas. The government didn't initially buy the land. Instead, they paid the Thomases five shillings for the right to build the lighthouse, and John Thomas became the first keeper of the lights.

The first lighthouse on the high bluff at the eastern end of the Gurnet was authorized by an act of the colonial legislature on February 17, 1768.

The structure, built for 660 pounds, took the form of a wooden dwelling with a lantern at each end of its roof, which made this the site of North America's first "twin lights."

The lights were in operation by September 1768. The station was built on land owned by John and Hannah Thomas. The government didn't initially buy the land. Instead, they paid the Thomases five shillings for the right to build the lighthouse, and John Thomas became the first keeper of the lights.

In the days leading up to the American Revolution, John Thomas recruited a regiment of volunteers from Plymouth County. In March 1775, Thomas and his men fortified Dorchester Heights at Boston, which led to the withdrawal of the British. Thomas became a major general and led troops at Quebec. Smallpox spread through his troops, and Thomas died of the disease on June 2, 1776.

A view of the Gurnet circa 1901, courtesy of Paul Christian

Thomas's wife, Hannah, had taken over the duties of keeping the lights at the Gurnet when her husband went to war, along with the responsibilities of raising three children. She was America's first woman lighthouse keeper.

During the Revolution, the towns of Plymouth, Duxbury and Kingston built a fort on the Gurnet. Local folklore has it that the British frigate Niger fired on the fort and one of the cannonballs pierced the lighthouse building.

One of the most famous New England shipwrecks happened near the Gurnet in December 1778, when the American brigantine General Arnold tried to anchor about a mile from the point and struck White Flats. Seventy-two men on the ship perished in the freezing water. The keeper at the Gurnet was unable to reach the vessel because of the ice floes that filled the harbor. Local residents eventually built a causeway to the ship to rescue the survivors.

In 1786, Hannah Thomas hired a local man named Nathaniel Burgess (or Burges) to serve as lightkeeper. John Thomas, son of Hannah and John, had done much of the work at the station for years by the time he received the official appointment as keeper in 1790. The lighthouse was ceded to the federal government in the same year. John Thomas remained keeper until 1812. The next keeper, Joseph Burgess -- son of Nathaniel Burgess -- had a long 39-year stint.

The original twin light structure served until June 30, 1801, when it was destroyed by fire. The merchants of Duxbury and Plymouth paid for a temporary structure, which itself was nearly consumed by fire in early 1802. Congress appropriated $2,500 for the rebuilding of the station in April 1802. The local merchants were repaid $270 for their expenses.

During the Revolution, the towns of Plymouth, Duxbury and Kingston built a fort on the Gurnet. Local folklore has it that the British frigate Niger fired on the fort and one of the cannonballs pierced the lighthouse building.

One of the most famous New England shipwrecks happened near the Gurnet in December 1778, when the American brigantine General Arnold tried to anchor about a mile from the point and struck White Flats. Seventy-two men on the ship perished in the freezing water. The keeper at the Gurnet was unable to reach the vessel because of the ice floes that filled the harbor. Local residents eventually built a causeway to the ship to rescue the survivors.

In 1786, Hannah Thomas hired a local man named Nathaniel Burgess (or Burges) to serve as lightkeeper. John Thomas, son of Hannah and John, had done much of the work at the station for years by the time he received the official appointment as keeper in 1790. The lighthouse was ceded to the federal government in the same year. John Thomas remained keeper until 1812. The next keeper, Joseph Burgess -- son of Nathaniel Burgess -- had a long 39-year stint.

The original twin light structure served until June 30, 1801, when it was destroyed by fire. The merchants of Duxbury and Plymouth paid for a temporary structure, which itself was nearly consumed by fire in early 1802. Congress appropriated $2,500 for the rebuilding of the station in April 1802. The local merchants were repaid $270 for their expenses.

A new pair of 22-foot- high twin towers was built in 1803, 30 feet apart, exhibiting fixed white lights 70 feet above sea level. The land at the Gurnet was finally bought outright, as the Thomases were paid $120.

Courtesy of Paul Christian

An 1842 inspection report recommended the immediate rebuilding reconstruction of the station's buildings. The towers were in such poor condition that even Stephen Pleasanton, the fifth auditor of the Treasury Department, who was in charge of the nation's lighthouses and a notorious penny- pincher, corroborated the urgent need to rebuild in April 1842. "I am afraid they will fall to the ground in the course of the summer," he wrote. There were also many complaints that the two lights blended into one from a distance and were easily confused with Barnstable's Sandy Neck Light.

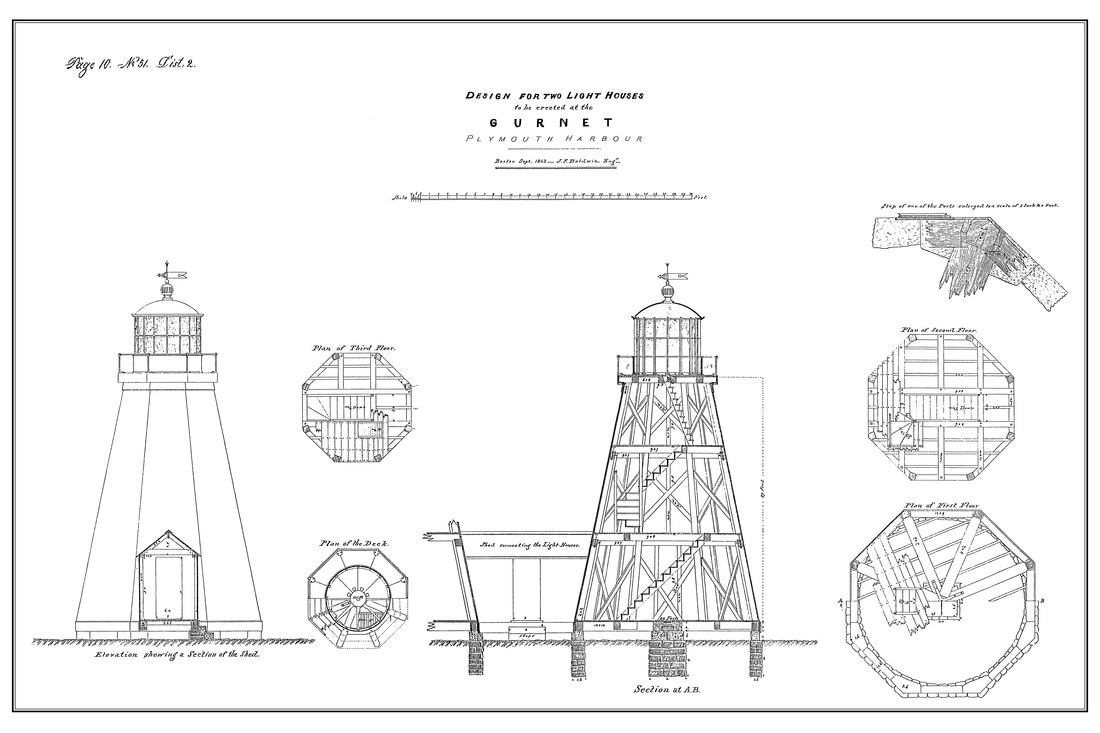

New octagonal wooden towers, joined by a covered walkway, were completed during 1843. A spacious new keeper's house was built at the same time.

The towers were so close together that the problem of the lights merging when seen from sea remained.

Right: This photo of neighboring property at the Gurnet is courtesy of Paul Christian, who says it is from a glass negative that probably dates from 1880-1900. He says it "was taken from the farmhouse looking towards the lighthouses. The building on the left is the farmhouse barn which burned down in 1924."

The 1843 twin lights would remain jointly in service at their original locations until 1924. Along the way, the old multiple lamps and reflectors were replaced by sixth-order Fresnel lenses, which were later upgraded to fourth-order lenses.

Right: This photo of neighboring property at the Gurnet is courtesy of Paul Christian, who says it is from a glass negative that probably dates from 1880-1900. He says it "was taken from the farmhouse looking towards the lighthouses. The building on the left is the farmhouse barn which burned down in 1924."

The 1843 twin lights would remain jointly in service at their original locations until 1924. Along the way, the old multiple lamps and reflectors were replaced by sixth-order Fresnel lenses, which were later upgraded to fourth-order lenses.

A 1904 article by Arthur Hewitt described a visit with the keeper at that time, Willis Higgins:

The 1843 Plymouth Lights

I pictured Higgins, the keeper, cleaning one of his lanterns, made friends with the patrolmen of the coast, caught more fish in the channel in an hour than one generally gets in a month, watched the porgy seiners and lobstermen, and thoroughly enjoyed this almost deserted spot.

Higgins and I often chatted. We disagreed on only one subject. I wanted Higgins to be photographed in the knockabout clothes he usually wore -- he called them his undress uniform -- but he vetoed this each time, and immediately donned the full regalia of the United States Lighthouse Establishment. . . . He was a representative of the United States Government, and wished to be treated as such.

A fog- bell tower, with a 1,500-pound bell and automatic striking machinery, was added to the station in 1907. A first-class Daboll fog trumpet eventually replaced the bell, with and a new building was erected for the related equipment.

Higgins and I often chatted. We disagreed on only one subject. I wanted Higgins to be photographed in the knockabout clothes he usually wore -- he called them his undress uniform -- but he vetoed this each time, and immediately donned the full regalia of the United States Lighthouse Establishment. . . . He was a representative of the United States Government, and wished to be treated as such.

A fog- bell tower, with a 1,500-pound bell and automatic striking machinery, was added to the station in 1907. A first-class Daboll fog trumpet eventually replaced the bell, with and a new building was erected for the related equipment.

The importance of the station decreased as maritime commerce fell off in Plymouth, but it later grew in importance again after the 1914 opening of the Cape Cod Canal led to more shipping traffic in the vicinity. By the 1920s, the twin light stations established on the East Coast were being phased out.

In 1924, as part of this effort, the northeast light at the Gurnet was discontinued and torn down, ending 156 years of twin lights on the site.

The single light was given a new characteristic, with a single flash alternating with a double flash every 20 seconds. The surviving 39-foot shingled tower is the nation's oldest freestanding lighthouse tower built only of wood.

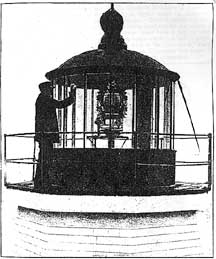

Right: Arthur Hewitt's picture of Keeper Higgins cleaning the lantern.

The single light was given a new characteristic, with a single flash alternating with a double flash every 20 seconds. The surviving 39-foot shingled tower is the nation's oldest freestanding lighthouse tower built only of wood.

Right: Arthur Hewitt's picture of Keeper Higgins cleaning the lantern.

Frank Allen Davis, previously in charge at Tarpaulin Cove Light, became keeper in 1929.

The Davis family hunted ducks and geese on the Gurnet, and the keeper's son, Frank Arthur Davis, became a licensed lobsterman at the age of nine. By the time he was 10, Frank was sailing his own boat and hauling his own lobster traps. He loved growing up at the Gurnet, later comparing his early life to those of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer:

From the time I could walk, I had boats, fishing, hunting and the run of the entire area. In the summer, I could play in the clumps of bushes and scrub cedar trees on the beach; the sand dunes were my mountains. I was king of the marshland and beach-creeks were my great rivers of the world.

Left: This photo, taken before 1924, is courtesy of Paul Christian. The boy on the fence near the lighthouse is Bill Jacobs, who was Paul's uncle and a local lobsterman who fished until he was 69.

From the time I could walk, I had boats, fishing, hunting and the run of the entire area. In the summer, I could play in the clumps of bushes and scrub cedar trees on the beach; the sand dunes were my mountains. I was king of the marshland and beach-creeks were my great rivers of the world.

Left: This photo, taken before 1924, is courtesy of Paul Christian. The boy on the fence near the lighthouse is Bill Jacobs, who was Paul's uncle and a local lobsterman who fished until he was 69.

The old dwelling was destroyed and a new four-bedroom ranch house was built to house the Coast Guard crew in 1962.

The Coast Guard announced plans to automate and destaff the light in the mid-1980s, and many local residents objected.

Right: This ranch-style house became the keeper's quarters in 1962; the old house was destroyed.

Boatswain's Mate First Class Joseph Robicheau, the officer in charge, was an emergency medical technician, and the only mobile firefighting equipment on the Gurnet was at the station.

Right: This ranch-style house became the keeper's quarters in 1962; the old house was destroyed.

Boatswain's Mate First Class Joseph Robicheau, the officer in charge, was an emergency medical technician, and the only mobile firefighting equipment on the Gurnet was at the station.

The light was officially automated on October 1, 1986, when a modern optic replaced the fourth-order Fresnel lens.

Left: Al Readdy, a Coast Guard heeper of Plymouth Lighthouse in 1951, polishes the fourth-order Fresnel lens. Courtesy of Al Readdy.

In 1989, the station was leased by the Coast Guard to the Massachusetts Chapter of the U.S. Lighthouse Society. Volunteers lived in the 1963 ranch keeper's house, and the property was open to overnight visitors.

Caretakers Bill and Debbi Ricci were married at the lighthouse and made many improvements to the property during their stay there.

The lease later reverted to the Coast Guard. In 1994, Plymouth Light was converted to solar power.

In 1989, the station was leased by the Coast Guard to the Massachusetts Chapter of the U.S. Lighthouse Society. Volunteers lived in the 1963 ranch keeper's house, and the property was open to overnight visitors.

Caretakers Bill and Debbi Ricci were married at the lighthouse and made many improvements to the property during their stay there.

The lease later reverted to the Coast Guard. In 1994, Plymouth Light was converted to solar power.

There were plans to move the lighthouse back from the eroding cliff in 1997, but neighbors complained that trucks would damage the fragile dirt roads on the Gurnet and that the lighthouse would be too close to their homes.

After discussion between residents and the Coast Guard, the lighthouse was moved by the Northern Construction Service, LLC, of Hingham, Massachusetts, in December 1998. The tower was moved approximately 140 feet.

Left: The lighthouse being moved in December 1998. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Project Gurnet and Bug Lights, a group responsible for the restoration of Duxbury Pier ("Bug") Light near Plymouth, acquired a lease for the lighthouse in May 1999. The group also now maintains the 1963 ranch-style keepers' quarters.

Left: The lighthouse being moved in December 1998. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Project Gurnet and Bug Lights, a group responsible for the restoration of Duxbury Pier ("Bug") Light near Plymouth, acquired a lease for the lighthouse in May 1999. The group also now maintains the 1963 ranch-style keepers' quarters.

Volunteers have painted the lighthouse in recent years, and a window was replaced in 2001. In addition, rugosa roses and bayberry bushes have been planted to guard against erosion.

Right: Dolly Bicknell, president of Project Gurnet & Bug Lights. Dolly's father was Edward Rowe Snow, famous historian and "Flying Santa" to lighthouses.

The light remains an active aid to navigation, with a sequence of three white flashes every 30 seconds. It was converted to solar power in 1994. A red sector warns mariner of dangerous Mary Ann Rocks, and there's an automated foghorn sounding two blasts every 15 seconds.

Automobile access to the Gurnet is limited to residents, but an open house is held in late May each year by Project Gurnet and Bug Lights as part of the Opening of the Bay festival in Duxbury.

For more information: Project Gurnet and Bug Lights, P. O. Box 2167, Duxbury, MA 02331

The former keepers' house can be rented by the week or by the month. Rents vary depending upon the month and season. For more information, see www.buglight.org

The light remains an active aid to navigation, with a sequence of three white flashes every 30 seconds. It was converted to solar power in 1994. A red sector warns mariner of dangerous Mary Ann Rocks, and there's an automated foghorn sounding two blasts every 15 seconds.

Automobile access to the Gurnet is limited to residents, but an open house is held in late May each year by Project Gurnet and Bug Lights as part of the Opening of the Bay festival in Duxbury.

For more information: Project Gurnet and Bug Lights, P. O. Box 2167, Duxbury, MA 02331

The former keepers' house can be rented by the week or by the month. Rents vary depending upon the month and season. For more information, see www.buglight.org

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Thomas (1769-1776); Hannah Thomas (1776-c.1790); John Thomas (son, 1790-1812); Joseph Burges [Burgess ?] (1812-1851); Thomas Treble (1851-); William Sears (1863-1881); Milton Reamy (1881-1887); Edward S. Gorham (1887-1892); Henry L. Pingree (1892-1894); Alfred Eisener (1894-1903); Willis Higgins (1903-1912); Carl Delano Hill (c. 1912); Francis R. Macy (first assistant, 1923-1926); Chester Wheeler (c. 1928); Frank Allen Davis (1929-1946); BM1 William Miller (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1957); BMC Earle B. Ashby (c. 1951); Al Readdy (Coast Guard, 1951); Robert Beaudry (Coast Guard, 1973-1974); Lorne Bair (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Joseph Robicheau (Coast Guard, December 1984 to March 1987).

John Thomas (1769-1776); Hannah Thomas (1776-c.1790); John Thomas (son, 1790-1812); Joseph Burges [Burgess ?] (1812-1851); Thomas Treble (1851-); William Sears (1863-1881); Milton Reamy (1881-1887); Edward S. Gorham (1887-1892); Henry L. Pingree (1892-1894); Alfred Eisener (1894-1903); Willis Higgins (1903-1912); Carl Delano Hill (c. 1912); Francis R. Macy (first assistant, 1923-1926); Chester Wheeler (c. 1928); Frank Allen Davis (1929-1946); BM1 William Miller (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1957); BMC Earle B. Ashby (c. 1951); Al Readdy (Coast Guard, 1951); Robert Beaudry (Coast Guard, 1973-1974); Lorne Bair (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Joseph Robicheau (Coast Guard, December 1984 to March 1987).