History of Burnt Island Light, Boothbay Harbor, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

One approaching Boothbay Harbor from the sea, whether from southward or eastward, heads toward one of the most beautiful harbor lighthouses on the entire Atlantic Coast -- Burnt Island Light. The shining whitewashed tower stands in bold contrast to the backdrop of dark evergreens and offers a tacit but cheery welcome to the waterborne visitor. This lighthouse is a guide, not a warning. - Malcolm F. Willoughby, The Boothbay Register, 1962

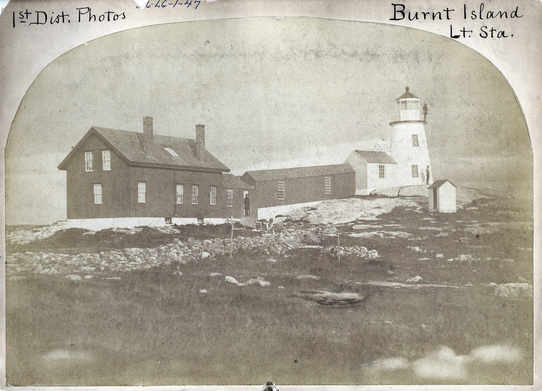

Circa 1859 (National Archives).

The town of Boothbay—originally known as Townsend and encompassing an area that now includes the towns of Boothbay, Boothbay Harbor, and Southport—was a center for shipbuilding, gristmills, and fishing in the 1700s. In 1764, local mariners and merchants petitioned the government for a lighthouse on Damariscove Island, five miles south of Boothbay Harbor.

The petition stated that a lighthouse at that location would serve to guide vessels to the Sheepscot River and Boothbay, and would also help those vessels passing along the coast. Two vessels, according to the petition, had been wrecked at Damariscove Island in the previous winter with some loss of life.

Damariscove Island never got a lighthouse, and soon the Revolution and the War of 1812 slowed the local economy. Coastal trade and fishing were again on the rise by 1820.

On March 3, 1821, Congress appropriated $10,500 for three lighthouses on the Maine coast, one of them on Burnt Island at the west side of the entrance to Boothbay Harbor. The federal government acquired the five-acre island two months later from Jacob Abed and Joseph McCobb for $150.

The petition stated that a lighthouse at that location would serve to guide vessels to the Sheepscot River and Boothbay, and would also help those vessels passing along the coast. Two vessels, according to the petition, had been wrecked at Damariscove Island in the previous winter with some loss of life.

Damariscove Island never got a lighthouse, and soon the Revolution and the War of 1812 slowed the local economy. Coastal trade and fishing were again on the rise by 1820.

On March 3, 1821, Congress appropriated $10,500 for three lighthouses on the Maine coast, one of them on Burnt Island at the west side of the entrance to Boothbay Harbor. The federal government acquired the five-acre island two months later from Jacob Abed and Joseph McCobb for $150.

The rubblestone tower, 20 feet tall to the base of the lantern, was accompanied by a small keeper’s house, also constructed of stone. The tower was topped by an octagonal wrought-iron lantern, seven feet high, containing lighting apparatus consisting of 10 whale oil lamps and corresponding 13-inch reflectors. The light went into service in November 1821.

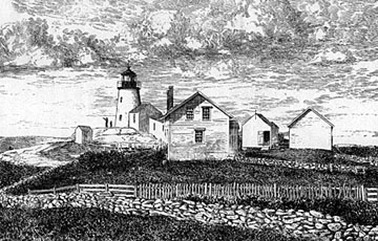

Engraving from the 1880s

Not much is known about the first keeper, a man named Marr. Joseph Prescott Chandler, who was born in 1776 in New Hampton, New Hampshire, succeeded him in 1830.

Elizabeth Oakes Smith later wrote about visits to the island around 1830:

I often went to the Light, taking my baby with me and passed a whole day with the family of the keeper regaled with shortcakes and strawberries and cream. They were a simple pious family and always gave me a warm welcome. . . . Mr. Chandler, the keeper, used to go out in his wherry to fish, and in good weather to row himself up to the village for the newspaper, leaving his somewhat delicate wife and her two children alone on the island.

Elizabeth Oakes Smith later wrote about visits to the island around 1830:

I often went to the Light, taking my baby with me and passed a whole day with the family of the keeper regaled with shortcakes and strawberries and cream. They were a simple pious family and always gave me a warm welcome. . . . Mr. Chandler, the keeper, used to go out in his wherry to fish, and in good weather to row himself up to the village for the newspaper, leaving his somewhat delicate wife and her two children alone on the island.

During one of Oakes’s visits, she was informed that on the previous day the keeper’s wife and children had watched a sea serpent, 30 feet long, swimming close to the island. Chandler’s wife, Hannah (Cram), told Oakes that she “expected every moment he would come on shore, and there was no telling what he would do.”

An 1843 inspection revealed problems with the dwelling: “Cellar overflows, and damages the flooring timbers above; drain useless; should be taken up and relaid.” An 1850 inspection, when Franklin Jones was keeper, found the lantern glass cracked, the lantern leaky, and the dwelling’s roof in need of shingling, but the station was otherwise in good order.

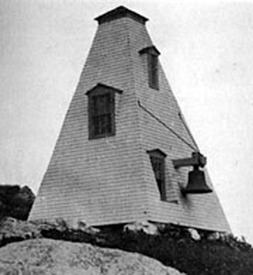

A new lantern and a fourth-order Fresnel lens were installed in 1856. In 1857, the originally dwelling was torn down and replaced by a new one-and-one-half- story, wood-frame cottage. A walkway between the tower and house was also added in 1857. The boathouse and oil house that still remain were built in 1880 and 1899 respectively. A fog bell tower and a 1,029-pound bell with automatic striking machinery, were added in 1895.

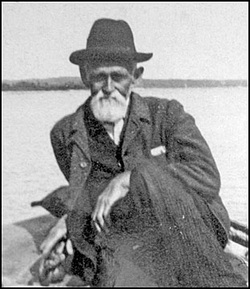

Left: James A. McCobb, keeper 1868-80. Courtesy of Maine Department of Marine Resources.

James A. McCobb, keeper from 1868 to 1880, was a former sea captain who settled down for the quieter life of a lighthouse keeper at the age of 50. In an 1869 letter, McCobb expressed his happiness at Burnt Island. “I was never more contented in my life,” he wrote. “’Tis so much better than anything else I could do, and I should dread so much having to go to sea again.”

A new lantern and a fourth-order Fresnel lens were installed in 1856. In 1857, the originally dwelling was torn down and replaced by a new one-and-one-half- story, wood-frame cottage. A walkway between the tower and house was also added in 1857. The boathouse and oil house that still remain were built in 1880 and 1899 respectively. A fog bell tower and a 1,029-pound bell with automatic striking machinery, were added in 1895.

Left: James A. McCobb, keeper 1868-80. Courtesy of Maine Department of Marine Resources.

James A. McCobb, keeper from 1868 to 1880, was a former sea captain who settled down for the quieter life of a lighthouse keeper at the age of 50. In an 1869 letter, McCobb expressed his happiness at Burnt Island. “I was never more contented in my life,” he wrote. “’Tis so much better than anything else I could do, and I should dread so much having to go to sea again.”

McCobb’s wife, Martha (Holton), died on the island of cancer in March 1877 at the age of 53. There have purportedly been numerous sightings of a ghostly woman in white bedclothes on the island, and some have speculated that the apparition is the spirit of Martha McCobb.

Without his wife to help entertain them, McCobb often complained in his log (now at the National Archives) about the volume of visitors at the station. “Have not of late opened the lighthouse to visitors on Sunday,” he wrote in July 1879. “Am of the opinion that they could come some other day as well as Sunday.”

Right, Freeman Grover Jr., keeper 1880-90. Courtesy of Maine Department of Marine Resources.

In August 1890, he complained of a group that arrived on a Sunday: “Many of them acting as if I was just here to wait upon them and nothing else. More and more coming every year.” After he retired because of poor health, McCobb was succeeded by Freeman Grover Jr., a native of nearby Southport. Grover’s brother, Woodbury, served as an unofficial assistant keeper. Grover’s descendants still operate Grover’s Hardware Store in Boothbay Harbor.

In 1888, a “dead angle” was added to the light so it wouldn’t be seen on the approach to the Cuckolds Light, to the south, and confused with that light. It was changed in 1890 to fixed red with two white sectors, marking the clear channels into Boothbay Harbor, in 1890.

The fixed red light seen from some directions was a source of potential confusion with the fixed red light at Ram Island. The 1902 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that it had been changed again, to a red flash every five seconds, with white sectors, with the installation of a new fourth-order lens with bullseyes. The present characteristic is a red flash every six seconds with two white sectors.

Right, Freeman Grover Jr., keeper 1880-90. Courtesy of Maine Department of Marine Resources.

In August 1890, he complained of a group that arrived on a Sunday: “Many of them acting as if I was just here to wait upon them and nothing else. More and more coming every year.” After he retired because of poor health, McCobb was succeeded by Freeman Grover Jr., a native of nearby Southport. Grover’s brother, Woodbury, served as an unofficial assistant keeper. Grover’s descendants still operate Grover’s Hardware Store in Boothbay Harbor.

In 1888, a “dead angle” was added to the light so it wouldn’t be seen on the approach to the Cuckolds Light, to the south, and confused with that light. It was changed in 1890 to fixed red with two white sectors, marking the clear channels into Boothbay Harbor, in 1890.

The fixed red light seen from some directions was a source of potential confusion with the fixed red light at Ram Island. The 1902 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that it had been changed again, to a red flash every five seconds, with white sectors, with the installation of a new fourth-order lens with bullseyes. The present characteristic is a red flash every six seconds with two white sectors.

A bell tower (below) with a 1,029 pound fog bell was added in 1895.

For much of its history, this was a much sought-after family station. The island is close to the mainland and the trip for supplies was usually not difficult. In 1948, Sidney Baldwin wrote in Casting off from Boothbay Harbor:

Near to Mouse lies Burnt Island, where the light stands that marks the approach to the harbor, one of the most popular lights along the coast, made so by the friendliness of Keeper Joseph Muise and his wife and family. His wife, with three girls of school age, Adelle, Prudence and Ann, take a house in the Harbor through the school months, going out to the island in the summer.

The keeper from 1894 to 1909 was William Tarlton Holbrook, who had previously been at Halfway Rock Light. William A. Stetson, previously an assistant at Seguin Island, became keeper in September 1909. A number of his log entries in 1910 concern problems with the light’s revolving mechanism and with the fog bell’s striking apparatus. On September 5, he recorded that the bell was disabled, and on the next day he reported, “Fog signal operated by hand.”

Several times, Stetson went to the aid of disabled vessels near the island. Stetson and his wife welcomed several children born on the island during their 21-year stay.

Near to Mouse lies Burnt Island, where the light stands that marks the approach to the harbor, one of the most popular lights along the coast, made so by the friendliness of Keeper Joseph Muise and his wife and family. His wife, with three girls of school age, Adelle, Prudence and Ann, take a house in the Harbor through the school months, going out to the island in the summer.

The keeper from 1894 to 1909 was William Tarlton Holbrook, who had previously been at Halfway Rock Light. William A. Stetson, previously an assistant at Seguin Island, became keeper in September 1909. A number of his log entries in 1910 concern problems with the light’s revolving mechanism and with the fog bell’s striking apparatus. On September 5, he recorded that the bell was disabled, and on the next day he reported, “Fog signal operated by hand.”

Several times, Stetson went to the aid of disabled vessels near the island. Stetson and his wife welcomed several children born on the island during their 21-year stay.

Albert Staples, a native of Southwest Harbor, Maine, formerly at Boon Island and Wood Island in Maine and White Island Light in New Hampshire, succeeded Stetson in 1930. Staples enjoyed gardening and building his own radios, which he learned to do by taking a correspondence course from the National Radio Institute.

Joseph Muise. Courtesy of Maine Lighthouse Museum.

aStaples retired in 1936 and eventually returned to Southwest Harbor, where he worked in boatbuilding.

Joseph Muise, who was originally from Nova Scotia, succeeded Staples and moved to the island with his wife, Anna (Seavey) and their four children, with another on the way. Muise had previously been stationed at Moose Peak Light, Mount Desert Rock Light, Deer Island Thorofare Light, and Baker Island Light.

After the family’s arrival at Burnt Island, Muise wrote: “Here we are at last on our new station, and we like it greatly. We had a rough passage from Deer Island [Thorofare] Light. . . . On our way we stayed in Rockland overnight and Mrs. Muise called on relatives while there."

The Muise children always found plenty of entertainment on the island. With no chickens to occupy it, a chicken coop became a playhouse. Swimming, fishing, and beachcombing were favorite pastimes. Willard Muise later described the annual Christmastime visits of the “Flying Santa,” either Bill Wincapaw or Edward Rowe Snow, who would fly over the island to drop presents for the family. They would all run out and wave at the plane. “Santa must have thought to himself,” said Willard Muise, “look at all them idiots. They must be ‘island happy!’"

There was always good food, too. When the children woke up to the smell of lobsters cooking and biscuits baking, they knew that a local lobsterman had repaid their father for some kindness with a bunch of lobsters. One of Ann Muise’s specialties was rhubarb pie—“I can almost smell one cooking now,” Ann recalled during a visit to the island in 1999.

Ann also recalled that her father took great pride in the appearance of the station. “Dad always kept the property immaculate,” she said. “He prided himself on everything being shipshape, ready for inspection at any time.”

Coast Guardsman Joe Johansen, who maintained equipment at lighthouses, later described a visit to Burnt Island while the Muises were there: “We went to walk in the house to have a cup of coffee and we had to take our shoes off. You could see your face in the deck.”

Joseph Muise, who was originally from Nova Scotia, succeeded Staples and moved to the island with his wife, Anna (Seavey) and their four children, with another on the way. Muise had previously been stationed at Moose Peak Light, Mount Desert Rock Light, Deer Island Thorofare Light, and Baker Island Light.

After the family’s arrival at Burnt Island, Muise wrote: “Here we are at last on our new station, and we like it greatly. We had a rough passage from Deer Island [Thorofare] Light. . . . On our way we stayed in Rockland overnight and Mrs. Muise called on relatives while there."

The Muise children always found plenty of entertainment on the island. With no chickens to occupy it, a chicken coop became a playhouse. Swimming, fishing, and beachcombing were favorite pastimes. Willard Muise later described the annual Christmastime visits of the “Flying Santa,” either Bill Wincapaw or Edward Rowe Snow, who would fly over the island to drop presents for the family. They would all run out and wave at the plane. “Santa must have thought to himself,” said Willard Muise, “look at all them idiots. They must be ‘island happy!’"

There was always good food, too. When the children woke up to the smell of lobsters cooking and biscuits baking, they knew that a local lobsterman had repaid their father for some kindness with a bunch of lobsters. One of Ann Muise’s specialties was rhubarb pie—“I can almost smell one cooking now,” Ann recalled during a visit to the island in 1999.

Ann also recalled that her father took great pride in the appearance of the station. “Dad always kept the property immaculate,” she said. “He prided himself on everything being shipshape, ready for inspection at any time.”

Coast Guardsman Joe Johansen, who maintained equipment at lighthouses, later described a visit to Burnt Island while the Muises were there: “We went to walk in the house to have a cup of coffee and we had to take our shoes off. You could see your face in the deck.”

Tom Norton was the Coast Guard keeper in the late 1960s. He married Betsy Smith a month before he was assigned to the lighthouse. The couple had a son, Stuart Norton, during their time at the light station.

Circa 1940s photo from "Casting off from Boothbay Harbor" by Sidney Baldwin.

Before leaving in 1970, Tom Norton said, "If I could stay here I would re-enlist for another 20 years." "We've certainly got to know each other here," added Betsy.

In April 1962, Burnt Island Light became the last lighthouse in New England to be converted from kerosene to electricity. Then, in 1988, it became one of the last Maine lights to be automated. Today the light is produced by a modern 300 mm lens.

In 1969, two Fresnel lenses from Burnt Island went to the Rockland Coast Guard base; they are now at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland. The light and automatic fog signal remain active aids to navigation.

Paul Kelly became the Coast Guard keeper in 1971, moving to the island with his wife, Sharon, their four-month old son, Brandon, and their St. Bernard puppy, Morgan. Around the same time the Kellys moved in, a helicopter pad was added to the island. It was a good thing, too, because a short time later, Brandon lost a finger in an accident and had to be rushed to the Boothbay Hospital by helicopter.

The motor on the station’s boat died during the Kellys’ stay, and for three months they had to row to the mainland for supplies. In winter, they had to transfer groceries and other supplies essentials to a toboggan that was pulled to a boat at a dock. After landing the boat at the island, they had to load the groceries had to be loaded onto another toboggan and pulled them up the hill to the keeper’s house. One day, Sharon slipped and a bag of groceries ended up in the water. A week later she was able to scoop up most of the items using a long-handled net.

In April 1962, Burnt Island Light became the last lighthouse in New England to be converted from kerosene to electricity. Then, in 1988, it became one of the last Maine lights to be automated. Today the light is produced by a modern 300 mm lens.

In 1969, two Fresnel lenses from Burnt Island went to the Rockland Coast Guard base; they are now at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland. The light and automatic fog signal remain active aids to navigation.

Paul Kelly became the Coast Guard keeper in 1971, moving to the island with his wife, Sharon, their four-month old son, Brandon, and their St. Bernard puppy, Morgan. Around the same time the Kellys moved in, a helicopter pad was added to the island. It was a good thing, too, because a short time later, Brandon lost a finger in an accident and had to be rushed to the Boothbay Hospital by helicopter.

The motor on the station’s boat died during the Kellys’ stay, and for three months they had to row to the mainland for supplies. In winter, they had to transfer groceries and other supplies essentials to a toboggan that was pulled to a boat at a dock. After landing the boat at the island, they had to load the groceries had to be loaded onto another toboggan and pulled them up the hill to the keeper’s house. One day, Sharon slipped and a bag of groceries ended up in the water. A week later she was able to scoop up most of the items using a long-handled net.

The Kellys had a scare one night, when out of the blue they were awakened by creaking from inside the house and a voice shouting, “KELLY!” They searched the house and found no one, and there were no boats in sight. They decided it was the “ghost of the lighthouse.” The next time the “haunting” repeated itself, they simply pulled the covers over their heads and ignored it.

The Coast Guard keeper in 1973–74 was Jerry Marlowe, a native of South Carolina. Marlowe wasn’t thrilled with island lighthouse life, and neither were his wife and daughter. The Marlowes were told not to lock the door to the keeper’s house, but after visitors walked right in early one morning, Marlowe took to wedging a chair against the door.

Tom Norton was in charge from 1968 to early 1971. He moved to the island 27 days after marrying his wife, Betsy. “Going to Burnt Island was like having an extended honeymoon. We were young and ready for adventure and we absolutely loved it,” Betsy Norton said later.

Betsy made monthly shopping trips to the Brunswick Naval Air Station commissary, accompanied by the wives of two keepers at Cuckolds Light Station. The Nortons' son, Stuart, was born in a hospital on the mainland n March 1969.

In 1988, Burnt Island became one of the last Maine light stations to be automated and destaffed. The last keeper was Henry Sieg, who moved to the station with his wife, Jeanne, in 1983. The Siegs had two children born on the mainland during their stay. When it was almost time to leave the island, Sieg was interviewed for the New York Times. There were some things he wouldn’t miss, like rising at dawn to check the harbor’s buoys and late- night trips to switch on the foghorn. “I’ve got to tell my wife to remind me of those things when we’re getting ready to leave here, and I feel like crying,” Sieg said.

In February 1998, as part of the Maine Lights Program, the Maine Lighthouse Selection Committee approved the transfer of Burnt Island Light to the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Grants from the Stephen and Tabitha King Foundation, MBNA, and the Davis Foundation helped launch the restoration of the station.

Tom Norton was in charge from 1968 to early 1971. He moved to the island 27 days after marrying his wife, Betsy. “Going to Burnt Island was like having an extended honeymoon. We were young and ready for adventure and we absolutely loved it,” Betsy Norton said later.

Betsy made monthly shopping trips to the Brunswick Naval Air Station commissary, accompanied by the wives of two keepers at Cuckolds Light Station. The Nortons' son, Stuart, was born in a hospital on the mainland n March 1969.

In 1988, Burnt Island became one of the last Maine light stations to be automated and destaffed. The last keeper was Henry Sieg, who moved to the station with his wife, Jeanne, in 1983. The Siegs had two children born on the mainland during their stay. When it was almost time to leave the island, Sieg was interviewed for the New York Times. There were some things he wouldn’t miss, like rising at dawn to check the harbor’s buoys and late- night trips to switch on the foghorn. “I’ve got to tell my wife to remind me of those things when we’re getting ready to leave here, and I feel like crying,” Sieg said.

In February 1998, as part of the Maine Lights Program, the Maine Lighthouse Selection Committee approved the transfer of Burnt Island Light to the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Grants from the Stephen and Tabitha King Foundation, MBNA, and the Davis Foundation helped launch the restoration of the station.

Elaine Jones, a former science teacher and education director for the DMR, was named the director of the facility. She once explained her attraction to Burnt Island: “The five-acre island is close to the mainland, yet it is removed from the pace of life on the mainland.”

Elaine Jones (Courtesy of Elaine Jones)

A public tour and educational program is offered in summer. The Novelty, located at Pier 8 in Boothbay Harbor, serves as the ferry to the island. You can call (207) 633-2284 or click here for information.

Keepers of the Burnt Island Light, a 501(c)3 public charitable organization, was incorporated in 2008.The "Keepers" manage lighthouse programs and the gift shop with the assistance of volunteer docents and interpreters.

Burnt Island Light is clearly seen from many of the harbor cruises and other boats leaving Boothbay Harbor.

The attractive station is seen by thousands of tourists each year and is a highlight of one of the prettiest harbors in Maine. For more information, visit Maine Department of Marine Resources or Keepers of the Burnt Island Light.

Keepers of the Burnt Island Light, a 501(c)3 public charitable organization, was incorporated in 2008.The "Keepers" manage lighthouse programs and the gift shop with the assistance of volunteer docents and interpreters.

Burnt Island Light is clearly seen from many of the harbor cruises and other boats leaving Boothbay Harbor.

The attractive station is seen by thousands of tourists each year and is a highlight of one of the prettiest harbors in Maine. For more information, visit Maine Department of Marine Resources or Keepers of the Burnt Island Light.

Click below to hear an interview with Elaine Jones on the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast "Light Hearted"

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

? Marr (1821-1830); Joseph P. Chandler (1830-1841); Joseph C. Auld (1841-1845); Jason Fuller (1845-1849); Franklin Jones (1849-1853); William McKown (1853-1861); J. Auld (1861-1869); James A. McCobb (1868-1880); Freeman Grover, Jr. (1880-1890); James Burke (1890-1894); Willis Dolliver (1894); William T. Holbrook (1894-1909); William A. Stetson (1909-1930); Albert Staples (1930-1936); Joseph Muise (1936-1951); Benjamin Stockbridge (1951-1955); Ted Prescott (Coast Guard, c. 1955); James Buotte (1955-1958); James McCullough (1958-1962); Dana Hale (Coast Guard, 1962-1963), Edward O'Shea (Coast Guard officer in charge, September 1963 to spring 1965); Earl Alley (Coast Guard, 1965-1966); Richard Bown (Coast Guard, 1966-1967); Thomas Hassler (Coast Guard, 1967-1968); Thomas Norton (Coast Guard, 1968-1971); Paul Kelly (Coast Guard, 1971-1973); Jerry Marlowe (Coast Guard, 1973-1974), Randall Griffing (Coast Guard, 1974-1977), John Appleby (Coast Guard, 1977-1979); Stephen Pitchford (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Christopher Cooney (Coast Guard, 1980-1983); Henry Sieg (Coast Guard, 1983-1988)

? Marr (1821-1830); Joseph P. Chandler (1830-1841); Joseph C. Auld (1841-1845); Jason Fuller (1845-1849); Franklin Jones (1849-1853); William McKown (1853-1861); J. Auld (1861-1869); James A. McCobb (1868-1880); Freeman Grover, Jr. (1880-1890); James Burke (1890-1894); Willis Dolliver (1894); William T. Holbrook (1894-1909); William A. Stetson (1909-1930); Albert Staples (1930-1936); Joseph Muise (1936-1951); Benjamin Stockbridge (1951-1955); Ted Prescott (Coast Guard, c. 1955); James Buotte (1955-1958); James McCullough (1958-1962); Dana Hale (Coast Guard, 1962-1963), Edward O'Shea (Coast Guard officer in charge, September 1963 to spring 1965); Earl Alley (Coast Guard, 1965-1966); Richard Bown (Coast Guard, 1966-1967); Thomas Hassler (Coast Guard, 1967-1968); Thomas Norton (Coast Guard, 1968-1971); Paul Kelly (Coast Guard, 1971-1973); Jerry Marlowe (Coast Guard, 1973-1974), Randall Griffing (Coast Guard, 1974-1977), John Appleby (Coast Guard, 1977-1979); Stephen Pitchford (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Christopher Cooney (Coast Guard, 1980-1983); Henry Sieg (Coast Guard, 1983-1988)