History of Point Judith Lighthouse, Narragansett, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Point Judith, part of the town of Narragansett, extends more than a mile from the Rhode Island coast and markes the entrance to Narragansett Bay to the north and Block Island Sound to the south. Several Indian tribes -- predominately the Narragansetts -- were living in the area when English settlers arrived.

C. late 1800s. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell

The passage past Point Judith was a dangerous one, with a treacherous ledge to the west and frequent fog in the area. A day beacon at Point Judith dated back to before the American Revolution.

The origin of Point Judith's name is disputed. Some say it was after the wife or mother-in-law of merchant John Hull, others say it was named for the Tribe of Judah in the Bible. The most colorful explanation concerns a Nantucket sea captain, lost in the fog off the point. The captain's daughter shouted that she spotted land. The captain, unable to discern anything in the fog, exhorted his daughter to "P'int, Judy, p'int!"

The first lighthouse was built at Point Judith in 1810 for $5,000. This octagonal wooden tower, the third lighthouse in Rhode Island, was destroyed in a severe hurricane in September 1815. A 35-foot stone lighthouse was erected the following year.

The new tower had a revolving light. In 1838, it was reported that the mechanism, powered by a weight of more than 200 pounds, took 144 seconds to complete a revolution. This was six seconds slower than intended. The revolving light was necessary to differentiate Point Judith from Beavertail Light.

The origin of Point Judith's name is disputed. Some say it was after the wife or mother-in-law of merchant John Hull, others say it was named for the Tribe of Judah in the Bible. The most colorful explanation concerns a Nantucket sea captain, lost in the fog off the point. The captain's daughter shouted that she spotted land. The captain, unable to discern anything in the fog, exhorted his daughter to "P'int, Judy, p'int!"

The first lighthouse was built at Point Judith in 1810 for $5,000. This octagonal wooden tower, the third lighthouse in Rhode Island, was destroyed in a severe hurricane in September 1815. A 35-foot stone lighthouse was erected the following year.

The new tower had a revolving light. In 1838, it was reported that the mechanism, powered by a weight of more than 200 pounds, took 144 seconds to complete a revolution. This was six seconds slower than intended. The revolving light was necessary to differentiate Point Judith from Beavertail Light.

The station was cold and damp, and the bedroom was located in the attic of the keeper's house. The keeper and his family are said to have slept in the kitchen to keep warm in the winter.

Late 1800s; 1857 lighthouse and keeper's house.

U.S. Coast Guard.

(In 1838 an inspector reported that the ten lamps and reflectors were in poor condition and that ice on the lantern glass was a common problem. Despite the lighthouse, frequent wrecks continued in the vicinity. In 1855 alone, 16 vessels were wrecked or stranded near Point Judith.

Edgar Ravenswood Eaton was keeper from 1849 to 1853. The site was inspected in the summer of 1850, and it was reported that the tower needed repointing and whitewashing, and the lantern was in need of repainting. The dwelling was “somewhat decayed in or about the sills,” and the windows were leaky. The lighting apparatus was clean and in good order, but it was reported that Keeper Eaton, “without doubt, burns oil to a waste.”

In the files of the Newport Historical Society is a stern letter to Eaton dated November 18, 1850, from Edward Lawton, the local lighthouse superintendent. Lawton wrote:

Complaint has been made at this office that your Light was out from two to half past 4 o’clock this morning; how much longer the complainant could not tell. I presume it is not necessary for me to say that such an occurrence is altogether inadmissible; your light is an important one & the consequences from missing it are serious indeed—if your oil is not good or the revolving apparatus is out of order let me know immediately, and I beg of you let no more complaints be made that the lights are out.

Eaton offered a poignant defense, illustrating an essential dilemma of lighthouse keepers at times of family illnesses:

Sir I was up all night tending to a sick child and was at the Light house after 1 oclock at night it was then a bright light . . . . I was out doors about four o’clock in the morning and the light was bright then I am serting. [sic]

In 1857, a new 51-foot brownstone tower and brick dwelling, connected to the tower by an enclosed walkway, were built. The lighthouse, which still stands, is an octagonal structure. It was fitted with a fourth-order Fresnel lens from Paris; this lens remains in place today. The upper half of the tower was later (in 1899) painted brown and the lower half white.

Edgar Ravenswood Eaton was keeper from 1849 to 1853. The site was inspected in the summer of 1850, and it was reported that the tower needed repointing and whitewashing, and the lantern was in need of repainting. The dwelling was “somewhat decayed in or about the sills,” and the windows were leaky. The lighting apparatus was clean and in good order, but it was reported that Keeper Eaton, “without doubt, burns oil to a waste.”

In the files of the Newport Historical Society is a stern letter to Eaton dated November 18, 1850, from Edward Lawton, the local lighthouse superintendent. Lawton wrote:

Complaint has been made at this office that your Light was out from two to half past 4 o’clock this morning; how much longer the complainant could not tell. I presume it is not necessary for me to say that such an occurrence is altogether inadmissible; your light is an important one & the consequences from missing it are serious indeed—if your oil is not good or the revolving apparatus is out of order let me know immediately, and I beg of you let no more complaints be made that the lights are out.

Eaton offered a poignant defense, illustrating an essential dilemma of lighthouse keepers at times of family illnesses:

Sir I was up all night tending to a sick child and was at the Light house after 1 oclock at night it was then a bright light . . . . I was out doors about four o’clock in the morning and the light was bright then I am serting. [sic]

In 1857, a new 51-foot brownstone tower and brick dwelling, connected to the tower by an enclosed walkway, were built. The lighthouse, which still stands, is an octagonal structure. It was fitted with a fourth-order Fresnel lens from Paris; this lens remains in place today. The upper half of the tower was later (in 1899) painted brown and the lower half white.

A family dynasty of keepers that would span nearly a half-century began in 1862 when Joseph Whaley -- oldest of 11 children and a native of Narragansett -- arrived as keeper at a yearly salary of $350.

"Captain Joe" and his wife raised three daughters and a son in their 27 years at the lighthouse. Their son, Henry, would become the next keeper in 1889 (at $650 per year), staying until 1910.

Right: Keeper Joseph Whaley. Courtesy of Marise Whaley Sykes.

The Narragansett Times reported on the astounding number of vessels seen passing Point Judith from June 1, 1871, to June 1, 1872. Keeper Whaley counted 4,444 steamers, 2,183 sloops, 29,757 schooners, 728 brigs, 122 barks, and 23 other ships—numbers that attest to the continued value of the light and fog signal. An 1889 article in the Providence Journal at the time of Joe Whaley's retirement at age 70 described his typical duties. The oil lamp needed to be filled after "lighting up" at sunset, then again at 10 p.m. and at 2 a.m. The clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens needed to be rewound during the predawn hours.

During the day, the weather had to be monitored for the first sign of fog or storm, because the steam boiler for the siren had to be ready for business when visibility was low. Of course, the buildings and grounds had to be kept in top condition, and the brasswork and Fresnel lens had to be immaculate.

Right: Keeper Joseph Whaley. Courtesy of Marise Whaley Sykes.

The Narragansett Times reported on the astounding number of vessels seen passing Point Judith from June 1, 1871, to June 1, 1872. Keeper Whaley counted 4,444 steamers, 2,183 sloops, 29,757 schooners, 728 brigs, 122 barks, and 23 other ships—numbers that attest to the continued value of the light and fog signal. An 1889 article in the Providence Journal at the time of Joe Whaley's retirement at age 70 described his typical duties. The oil lamp needed to be filled after "lighting up" at sunset, then again at 10 p.m. and at 2 a.m. The clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens needed to be rewound during the predawn hours.

During the day, the weather had to be monitored for the first sign of fog or storm, because the steam boiler for the siren had to be ready for business when visibility was low. Of course, the buildings and grounds had to be kept in top condition, and the brasswork and Fresnel lens had to be immaculate.

The keepers also had to cordially show around any visitors to the lighthouse. It was not unusual for 200 or more visitors to arrive on a summer afternoon.

All in all, the keeper and his assistant had plenty to do "besides basking on the little stretch of green smoking their pipes," as Joe Whaley put it.

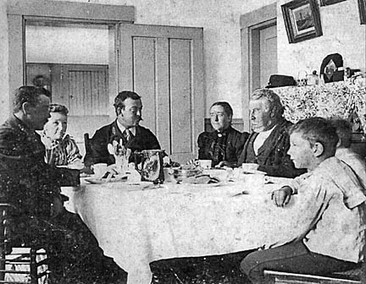

Left: The Whaleys around the dinner table. Joseph Whaley is second from right, and Henry Whaley is in the center. Courtesy of Marise Whaley Sykes.

Sometimes tricks of the weather meant that the powerful signal couldn't be heard even a short distance from the point. One ship captain complained to the authorities that the siren wasn't sounding properly, but Joe Whaley pointed out that the district lighthouse superintendent was with him in the signal house at the hour in question, along with a half dozen other people. The vagaries of nature were to blame, not the keeper.

One of Joe Whaley’s daughters married Henry W. Clark, keeper at Block Island Southeast Light, and another married Herbert Knowles, the longtime keeper of the nearby Point Judith Life Saving Station that had been established a short distance to the east of the lighthouse in 1876.

At his retirement, Whaley expressed some resentment about complaints:

You see it is a good deal of responsibility between the light and the fog signal. And I'm getting pretty old to shoulder it all, although my son Henry has relieved me of a good deal of it for years past. Why, every sailor man in the world has his eyes open to catch the lighthouse keepers and complain of them, and they do it every time they get a chance. That is all right, of course, for no one can watch the lighthouses and fog signals in times when they need watching except the sailor who happens to be going by and needs to have everything running all right. They make lots of funny complaints, though. Of course that about the fog signal not running is the most frequent, and I don't blame them either. But they watch to see whether your light is lit sharp at sunset, and if it goes out sharp at sunrise, and Block Island has been complained of several times for having the light burning after sunrise when it was the sun reflecting from the glass.

With heavy maritime traffic, wrecks continued to occur with regularity in the vicinity of Point Judith. On September 9, 1896, while Henry Whaley was keeper, a storm with winds of 80 miles per hour ran into the coast. At least five vessels were wrecked near Point Judith in the storm, and passengers on board the steamer Rhode Island reported that they received "a terrible shaking" while passing the point.

Left: The Whaleys around the dinner table. Joseph Whaley is second from right, and Henry Whaley is in the center. Courtesy of Marise Whaley Sykes.

Sometimes tricks of the weather meant that the powerful signal couldn't be heard even a short distance from the point. One ship captain complained to the authorities that the siren wasn't sounding properly, but Joe Whaley pointed out that the district lighthouse superintendent was with him in the signal house at the hour in question, along with a half dozen other people. The vagaries of nature were to blame, not the keeper.

One of Joe Whaley’s daughters married Henry W. Clark, keeper at Block Island Southeast Light, and another married Herbert Knowles, the longtime keeper of the nearby Point Judith Life Saving Station that had been established a short distance to the east of the lighthouse in 1876.

At his retirement, Whaley expressed some resentment about complaints:

You see it is a good deal of responsibility between the light and the fog signal. And I'm getting pretty old to shoulder it all, although my son Henry has relieved me of a good deal of it for years past. Why, every sailor man in the world has his eyes open to catch the lighthouse keepers and complain of them, and they do it every time they get a chance. That is all right, of course, for no one can watch the lighthouses and fog signals in times when they need watching except the sailor who happens to be going by and needs to have everything running all right. They make lots of funny complaints, though. Of course that about the fog signal not running is the most frequent, and I don't blame them either. But they watch to see whether your light is lit sharp at sunset, and if it goes out sharp at sunrise, and Block Island has been complained of several times for having the light burning after sunrise when it was the sun reflecting from the glass.

With heavy maritime traffic, wrecks continued to occur with regularity in the vicinity of Point Judith. On September 9, 1896, while Henry Whaley was keeper, a storm with winds of 80 miles per hour ran into the coast. At least five vessels were wrecked near Point Judith in the storm, and passengers on board the steamer Rhode Island reported that they received "a terrible shaking" while passing the point.

The old lifesaving station was destroyed in a 1933 fire, and the existing Coast Guard station building was constructed in 1937.

U.S. Coast Guard

Today, Coast Guard Station Point Judith handles about 170 search- and- rescue cases each year. The station’s boats are kept three miles away in Galilee. In 1931, a radio beacon was established at Point Judith, the first at a Rhode Island lighthouse. The radio beacon towers were removed in 1974.

Shipping traffic past Point Judith remained heavy in the 20th century. In 1907, 22,860 vessels were counted passing the lighthouse in daylight hours. The traffic was four times greater than the traffic entering New York Harbor.

The Coast Guard built larger quarters and support buildings in 1937. Point Judith Light escaped the great hurricane of September 1938 relatively unscathed, although 250 feet of the seawall was destroyed.

Shipping traffic past Point Judith remained heavy in the 20th century. In 1907, 22,860 vessels were counted passing the lighthouse in daylight hours. The traffic was four times greater than the traffic entering New York Harbor.

The Coast Guard built larger quarters and support buildings in 1937. Point Judith Light escaped the great hurricane of September 1938 relatively unscathed, although 250 feet of the seawall was destroyed.

The 1857 brick keeper's house was torn down in 1954, the same year the light was automated. An 1874 assistant keeper's house has also been destroyed. The 1917 oil house and a 1923 fog signal building still stand.

U.S. Coast Guard Station Point Judith

In the summer of 2000, Point Judith Light underwent a major restoration. Coast Guard architect Marsha Levy did the design work and oversaw the restoration by Campbell Construction of Beverly, Massachusetts.

The lens was removed to the Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team in Bristol, Rhode Island, and the lantern went to Campbell Construction for refurbishing. Some of the lantern's panels were replaced, and a repainting left it in pristine condition.

New galvanized steel windows with six panes of safety glass were installed, similar to the tower's original wrought iron windows.

The lens was removed to the Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team in Bristol, Rhode Island, and the lantern went to Campbell Construction for refurbishing. Some of the lantern's panels were replaced, and a repainting left it in pristine condition.

New galvanized steel windows with six panes of safety glass were installed, similar to the tower's original wrought iron windows.

Some of the original brownstone, which "weathers horribly" according to Levy, had to be replaced. Brownstone is hard to come by these days, but a quarry was found in Cheshire, Connecticut. The new stones were dyed to match the old ones. The project also utilized special mortar from Holland, which is custom formulated to match any stone. Cracks were patched on the interior and exterior of the tower. Rather than paint the upper half of the tower brown, Levy decided to leave it the natural brownstone color, with a dye making it slightly darker. According to Marsha Levy, the restoration should leave the tower in excellent condition for at least 100 years.

Point Judith remains an active Coast Guard station. Although the grounds have been open to the public in the past, they are now closed. There is a corrosion test facility (owned by Alcoa) next to the station. You can park outside the station and a trail leads past the test facility and around the Coast Guard station to the rocky beach, affording good photographic views of the lighthouse.

Point Judith remains an active Coast Guard station. Although the grounds have been open to the public in the past, they are now closed. There is a corrosion test facility (owned by Alcoa) next to the station. You can park outside the station and a trail leads past the test facility and around the Coast Guard station to the rocky beach, affording good photographic views of the lighthouse.

|

|

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John P. Whitford (1809-1835), Benjamin Hadwens (1841-1845), William A. Weeden (1845-1849), Edgar Ravenswood Eaton (1849-1853), G. H. Clark (1853-1856), Samuel Tucker (1856-1861), Daniel E. Tefft (1861-1862), Joseph Whaley (1862-1889), Edwin B. Tucker (1st asst., 1867), Henry W. Clark (1st asst., 1867-1873), Isaac Negas (1st asst., 1873), Benjamin A. King (1st asst., 1873-1874), Samuel Beaumont (1st asst., 1874), C. C. Clark (1st asst., 1874-1875), J. Sennett (1st asst., 1875-1876), Henry A. Whaley (1st asst., 1876-1889, keeper 1889-1910), William Nelson (1st asst., 1889), John Stedman (1st asst., 1889-1898), Harry Collins (1st asst., 1898-1901), Julius Gregove (1st asst., 1901-1904), Arthur E. Godfrey (1st asst., 1904-1906), Willis A. Green (1st asst., 1906-1910, keeper 1910-1911), J. N. (Julius ?) Gregove (1st asst., 1910-1911), Elmer J. Rathbun (1911-1929), A. D. Gilmore (1st asst., 1911-1918), Jeremiah J. Allen (1st asst., 1918-1929), Rudolph Iten (1929-1941), Carl S. Chellis (1st asst., 1929-1938), Octavius E. Davis (1st asst., 1939-1941)

John P. Whitford (1809-1835), Benjamin Hadwens (1841-1845), William A. Weeden (1845-1849), Edgar Ravenswood Eaton (1849-1853), G. H. Clark (1853-1856), Samuel Tucker (1856-1861), Daniel E. Tefft (1861-1862), Joseph Whaley (1862-1889), Edwin B. Tucker (1st asst., 1867), Henry W. Clark (1st asst., 1867-1873), Isaac Negas (1st asst., 1873), Benjamin A. King (1st asst., 1873-1874), Samuel Beaumont (1st asst., 1874), C. C. Clark (1st asst., 1874-1875), J. Sennett (1st asst., 1875-1876), Henry A. Whaley (1st asst., 1876-1889, keeper 1889-1910), William Nelson (1st asst., 1889), John Stedman (1st asst., 1889-1898), Harry Collins (1st asst., 1898-1901), Julius Gregove (1st asst., 1901-1904), Arthur E. Godfrey (1st asst., 1904-1906), Willis A. Green (1st asst., 1906-1910, keeper 1910-1911), J. N. (Julius ?) Gregove (1st asst., 1910-1911), Elmer J. Rathbun (1911-1929), A. D. Gilmore (1st asst., 1911-1918), Jeremiah J. Allen (1st asst., 1918-1929), Rudolph Iten (1929-1941), Carl S. Chellis (1st asst., 1929-1938), Octavius E. Davis (1st asst., 1939-1941)