History of Nobska Point Light, Woods Hole, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Falmouth on Cape Cod was named for Falmouth, England, home port of explorer Bartholomew Gosnold, who gave Cape Cod its name. At first the English settlement in the area retained its Indian name, Suckanesset; it was changed to Falmouth in 1690.

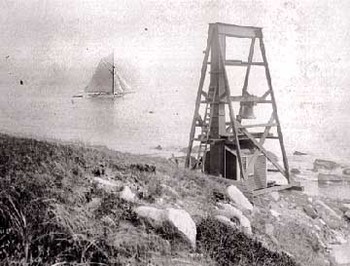

The first Nobska Point Light (U.S. Coast Guard)

One of Falmouth's villages,Woods Hole, with its deep harbor, developed a substantial whaling fleet in the early years of the nineteenth century. Besides the local maritime traffic, Nobska Point was passed by a stream of vessels crossing through Vineyard Sound, bordered by Falmouth and the Elizabeth Islands to the north, and Martha's Vineyard to the south. In 1829, the year the lighthouse was established, it was reported that more than 10,000 vessels passed through the area.

Prominent Nobska Point was an ideal place for a lighthouse. Congress appropriated $3,000 for that purpose on May 23, 1828, and the federal government purchased four acres for the light station from William and Hannah Lawrence, Andrew Davis, and Elizabeth Lawrence, at a cost of $160.

The first lighthouse, built in 1828 for $2,249, was a typical Cape Cod style structure with an octagonal lantern on top of the keeper's house. There were three rooms on the first floor of the dwelling, and two small rooms upstairs. The lantern held a lighting system of 10 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, displaying a fixed white light 78 feet above the sea. Like some similar lighthouses, this one had problems with leaks, as the lantern created too much stress on the roof.

Prominent Nobska Point was an ideal place for a lighthouse. Congress appropriated $3,000 for that purpose on May 23, 1828, and the federal government purchased four acres for the light station from William and Hannah Lawrence, Andrew Davis, and Elizabeth Lawrence, at a cost of $160.

The first lighthouse, built in 1828 for $2,249, was a typical Cape Cod style structure with an octagonal lantern on top of the keeper's house. There were three rooms on the first floor of the dwelling, and two small rooms upstairs. The lantern held a lighting system of 10 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, displaying a fixed white light 78 feet above the sea. Like some similar lighthouses, this one had problems with leaks, as the lantern created too much stress on the roof.

Because the light station was located on the mainland, the keeper was not provided with a boat. Lt. Edward Carpender surveyed Nobska Light in 1838 and recommended that an exception be made, saying, "Should the regulation be waived in favor of any one, I hope it will be extended to this individual, who once had it in his power, with the government boat, no longer serviceable, to rescue some persons from drowning."

In 1843, engineer I. W. P. Lewis issued a scathing report to Congress after inspecting the lighthouses of the northeast coast, but Nobska Light was spared. Lewis reported that the station was "in good order and repair."

Peter Daggett, a veteran of the War of 1812, was keeper in the 1840s. Some of Daggett’s papers are in the possession of the Falmouth Historical Society. It appears he was mostly generally a man of few words, although he did complain to the local superintendent several times about the poor quality of the oil he received for the light. In May 1847, he reported that he had whitewashed the lighthouse. “All that is wanting at this time,” Daggett wrote, “is a new pump to the cistern and a new sail for the boat and three sheat iorn [sic] pipes for the chimneys.”

Daggett was removed from the position in the summer of 1849, “for no other reason,” according to a contemporary newspaper, “than because he is a democrat.” The newspaper praised Daggett’s service: “No light in the world was better kept. Honesty, fidelity and capacity in the keeper were evident to all.” Lighthouse keeping positions were political appointments in those days, and there was no stopping the wheels of politics. William Davis became the next keeper.

Through much of the nineteenth century, the keepers had to count the vessels that passed the light. On one day alone in 1864, Keeper Frederick Ray counted 188 vessels—including 175 schooners—passing the point.

Peter Daggett, a veteran of the War of 1812, was keeper in the 1840s. Some of Daggett’s papers are in the possession of the Falmouth Historical Society. It appears he was mostly generally a man of few words, although he did complain to the local superintendent several times about the poor quality of the oil he received for the light. In May 1847, he reported that he had whitewashed the lighthouse. “All that is wanting at this time,” Daggett wrote, “is a new pump to the cistern and a new sail for the boat and three sheat iorn [sic] pipes for the chimneys.”

Daggett was removed from the position in the summer of 1849, “for no other reason,” according to a contemporary newspaper, “than because he is a democrat.” The newspaper praised Daggett’s service: “No light in the world was better kept. Honesty, fidelity and capacity in the keeper were evident to all.” Lighthouse keeping positions were political appointments in those days, and there was no stopping the wheels of politics. William Davis became the next keeper.

Through much of the nineteenth century, the keepers had to count the vessels that passed the light. On one day alone in 1864, Keeper Frederick Ray counted 188 vessels—including 175 schooners—passing the point.

In 1876, the lighthouse was rebuilt as a 40-foot cast-iron tower lined with brick, with a fifth-order Fresnel lens.

The fog bell ca. 1890s.

The individual sections of the lighthouse were cast in Chelsea, Massachusetts, and transported to Woods Hole in four sections. The new tower was painted a dark reddish-brown color.

The lens was upgraded to fourth-order in 1888, and a red sector was added to warn mariners of the dangerous L'Hommedieu and Hedge Fence shoals. New striking machinery for the fog bell was installed in the same year. Four years later, a 100-foot stone wall was added to protect the fog bell tower, which was closer to the water than the lighthouse. Further protection was added in 1900, and a new building was added to house the striking machinery.

A covered walkway joining the tower to the keeper's house was added in 1899, along with a new water cistern. A second dwelling for an assistant keeper and his family was added in 1907. The two houses were later joined.

The lens was upgraded to fourth-order in 1888, and a red sector was added to warn mariners of the dangerous L'Hommedieu and Hedge Fence shoals. New striking machinery for the fog bell was installed in the same year. Four years later, a 100-foot stone wall was added to protect the fog bell tower, which was closer to the water than the lighthouse. Further protection was added in 1900, and a new building was added to house the striking machinery.

A covered walkway joining the tower to the keeper's house was added in 1899, along with a new water cistern. A second dwelling for an assistant keeper and his family was added in 1907. The two houses were later joined.

Oliver A. Nickerson had the longest stay of any keeper in the station's history, from 1874 to 1911.

Boston Public Library

A 1908 article described the duties of the keeper's daughter, Florence Nickerson. For the previous seven years, she had been the official "observer" at Nobska, keeping track of all the vessels passing by in daylight hours. "She is shrewd and kindly," said the article, "one of those Yankee girls who fear nothing and take life cheerfully."

Besides her observational duties, Florence kept house at the station and tended a flock of chickens.

In 1910, a new brick fog signal building was erected, with a fog whistle operated by compressed air. The keepers started the signal when visibility dropped below five miles.

George I. Cameron of Southport, Maine—formerly at Graves Light and Baker’s Island Light Station, near Salem, Massachusetts—was in charge at the light station in early August 1911 when the Boston-bound steamer Bunker Hill, with more than 300 passengers on board, ran aground close to the light station on a clear night, in calm seas. “If the pilot or captain, whoever was in charge of the steamer, was trying to hit Nobska Lighthouse,” wrote one passenger, “he was a very poor shot, as he didn’t come within 100 feet of it, and if he was trying to avoid hitting it he was equally a poor shot, as he had plenty of water in the broad Vineyard sound to escape striking the beacon, the rays of which must nearly have blinded him as he was running his vessel toward it.” The steamer was backed off the rocks and made it to Vineyard Haven, where all the passengers were safely unloaded.

Besides her observational duties, Florence kept house at the station and tended a flock of chickens.

In 1910, a new brick fog signal building was erected, with a fog whistle operated by compressed air. The keepers started the signal when visibility dropped below five miles.

George I. Cameron of Southport, Maine—formerly at Graves Light and Baker’s Island Light Station, near Salem, Massachusetts—was in charge at the light station in early August 1911 when the Boston-bound steamer Bunker Hill, with more than 300 passengers on board, ran aground close to the light station on a clear night, in calm seas. “If the pilot or captain, whoever was in charge of the steamer, was trying to hit Nobska Lighthouse,” wrote one passenger, “he was a very poor shot, as he didn’t come within 100 feet of it, and if he was trying to avoid hitting it he was equally a poor shot, as he had plenty of water in the broad Vineyard sound to escape striking the beacon, the rays of which must nearly have blinded him as he was running his vessel toward it.” The steamer was backed off the rocks and made it to Vineyard Haven, where all the passengers were safely unloaded.

John M. Scharff had a long 30-year stay as keeper (1925–55). Early one morning in May 1930, the 15,000-ton steel freighter Kearny, with about 25 men on board, ran into the rocks near the lighthouse in a light fog. Keeper Scharff quickly phoned the Woods Hole Coast Guard station and aid was hurried to the vessel. There were no injuries.

In August 1935, Keeper Scharff and Assistant Keeper Waldo Leighton rescued a man who had fallen overboard from his sailboat in a squall.

The Coast Guard took over the management of lighthouses in 1939, but civilian keepers remained at Nobska Point Light until November 1973.

Osborne Hallett was in charge from 1955 to 1968, and Joseph Hindley was his assistant. Hindley took over as principal keeper in 1968.

When he retired in 1973, Hindley was believed to be the last civilian lighthouse keeper in New England. His career in the Lighthouse Service dated back to 1927, when he was an assistant at Whale Rock Light in Rhode Island.

The Coast Guard took over the management of lighthouses in 1939, but civilian keepers remained at Nobska Point Light until November 1973.

Osborne Hallett was in charge from 1955 to 1968, and Joseph Hindley was his assistant. Hindley took over as principal keeper in 1968.

When he retired in 1973, Hindley was believed to be the last civilian lighthouse keeper in New England. His career in the Lighthouse Service dated back to 1927, when he was an assistant at Whale Rock Light in Rhode Island.

At the time of their retirement and move to a home in East Falmouth, the keeper’s wife, Charlotte Hindley, said that the couple’s years at lighthouses were “very uneventful.” She observed, “People always try to romanticize it.” She said that after so many years of learning to talk between foghorn blasts, it would be hard to sleep without the sound.

Right: December 29, 1967: Osborne E. Hallett, Joseph G. Hindley Jr., and Harry A. Wilbur are awarded Gallatin Certificates by Capt. Frederick J. Hancox, commanding officer of Coast Guard Group Woods Hole. The men were the last three civilian lighthouse keepers in New England. (Wilbur was keeper at Warwick Light, Rhode Island.) Courtesy of Anne Ames.

The light was automated and the Coast Guard keepers were removed in 1985. The last officer in charge was Charles Tebo, who lived at the lighthouse with his wife, Gina, and their two young children.

The light was automated and the Coast Guard keepers were removed in 1985. The last officer in charge was Charles Tebo, who lived at the lighthouse with his wife, Gina, and their two young children.

After automation, the station became the home for the commander of U.S. Coast Guard Group Woods Hole, which was renamed in 2006 as Coast Guard Sector Southeastern New England. For some years the lighthouse was "adopted" by the members of Coast Guard Auxiliary Flotilla 11-02.

A wreath on the lighthouse in December 2003

There's a small parking area near the lighthouse, and the grounds are open to the public until dusk every day.

In April 2016, the Coast Guard granted a license for the property to the Town of Falmouth. Friends of Nobska Light is a nonprofit formed by the Falmouth Historical Society, Highfield Hall and Gardens, Woods Hole Historical Museum, and the Woods Hole Community Association.

“The mission of Friends of Nobska Light is the preservation and protection of this beloved landmark, to ensure its future enjoyment for the community and visitors,” the group said in a statement. Check their website for the schedule of lighthouse open houses.

Jim Jolin sent me the following note about Nobska Point Light and has kindly allowed me to share it on this page:

I had the distinct pleasure of growing up near Nobsque (Nobska) Light as a child. My grandparents had a home on Fay Road just off the Old Falmouth Road going towards Woods Hole. We lived on Buzzards Bay Avenue from 1951 to 1955.

One very foggy day as we rounded the bluff the "Deep Fog" horn went off just as we drove in front of it. My brother and I were so startled by the sound that we literally hit the inside of the roof. Though not injured badly, we were very surprised and had pretty sore heads. The lighthouse was a wonderful sight to see as it stands on a small bluff looking out towards Vineyard Sound. It was a faithful sentinel for lots of us who swam at nearby Old Falmouth Beach. I know that I always felt safer, for whatever childish reason, when I would see the lighthouse.

Even after we moved onto the mainland (Weymouth), I would always find a way to drive by when I came to Woods Hole. Thanks for letting me bring back great memories. -- Jim Jolin

In April 2016, the Coast Guard granted a license for the property to the Town of Falmouth. Friends of Nobska Light is a nonprofit formed by the Falmouth Historical Society, Highfield Hall and Gardens, Woods Hole Historical Museum, and the Woods Hole Community Association.

“The mission of Friends of Nobska Light is the preservation and protection of this beloved landmark, to ensure its future enjoyment for the community and visitors,” the group said in a statement. Check their website for the schedule of lighthouse open houses.

Jim Jolin sent me the following note about Nobska Point Light and has kindly allowed me to share it on this page:

I had the distinct pleasure of growing up near Nobsque (Nobska) Light as a child. My grandparents had a home on Fay Road just off the Old Falmouth Road going towards Woods Hole. We lived on Buzzards Bay Avenue from 1951 to 1955.

One very foggy day as we rounded the bluff the "Deep Fog" horn went off just as we drove in front of it. My brother and I were so startled by the sound that we literally hit the inside of the roof. Though not injured badly, we were very surprised and had pretty sore heads. The lighthouse was a wonderful sight to see as it stands on a small bluff looking out towards Vineyard Sound. It was a faithful sentinel for lots of us who swam at nearby Old Falmouth Beach. I know that I always felt safer, for whatever childish reason, when I would see the lighthouse.

Even after we moved onto the mainland (Weymouth), I would always find a way to drive by when I came to Woods Hole. Thanks for letting me bring back great memories. -- Jim Jolin

Listen to an interview with Catherine Bumpus, director of the Friends of Nobska Light, on the podcast "Light Hearted":

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Peter Daggett (?-1849); William Davis (1849-1853); William Ferguson Jr. (1853-1861); Frederick Ray (1861-1874); Oliver A. Nickerson (1874-1911); George I. Cameron (assistant 1910-1911, principal keeper 1911-?); John M. Scharff (1925-1955); Waldo Leighton, assistant (c. 1935); George T. Gustavus (assistant 1911-?, principal keeper 1939-1941); Joseph G. Hindley, Jr. (assistant, c. 1956-1968, keeper 1968-1972); Osborne E. Hallett (1955-1968)

Peter Daggett (?-1849); William Davis (1849-1853); William Ferguson Jr. (1853-1861); Frederick Ray (1861-1874); Oliver A. Nickerson (1874-1911); George I. Cameron (assistant 1910-1911, principal keeper 1911-?); John M. Scharff (1925-1955); Waldo Leighton, assistant (c. 1935); George T. Gustavus (assistant 1911-?, principal keeper 1939-1941); Joseph G. Hindley, Jr. (assistant, c. 1956-1968, keeper 1968-1972); Osborne E. Hallett (1955-1968)