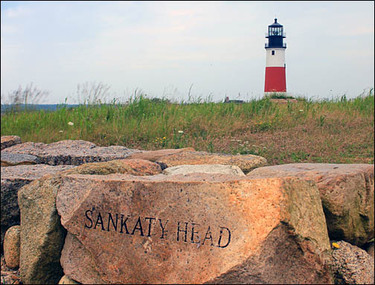

History of Sankaty Head Light, Nantucket, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Nantucket, the world’s leading whaling port for about a century, had lighthouses at Brant Point and Great Point by 1784. Meanwhile, the island’s east and south coasts remained devoid of lighthouses well into the nineteenth century, in spite of the high volume of shipping traffic passing the island and the presence of dangerous shoals.

The name “Sankaty” is said to come from a Wampanoag word for a highland or “cool hill.” Local tradition informs us that the bluffs, nearly 100 feet high, were used as a lookout for whales by some of the early European settlers, who went after whales close to shore before advancing to longer expeditions.

In his influential 1843 report to Congress, the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis wrote:

There is a... fatal spot upon the coast of Massachusetts, where many a brave heart and many a gallant ship lie buried in one common grave. The shoals of Nantucket are known and dreaded by every navigator on the Atlantic seaboard... and it is really very remarkable that this most striking omission in the lighting of our sea coast has not before been observed. By establishing a powerful light on the southeastern elbow of Nantucket Island, all the vessels that now feel their dubious way around the South shoal... could coast the south shore of the island, and pass between Sancoty Head and Bass rip in a deep safe channel... The establishment of a light-house at Siasconsett would be more generally useful to the commerce of the United States than any other position on the seaboard.

In his influential 1843 report to Congress, the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis wrote:

There is a... fatal spot upon the coast of Massachusetts, where many a brave heart and many a gallant ship lie buried in one common grave. The shoals of Nantucket are known and dreaded by every navigator on the Atlantic seaboard... and it is really very remarkable that this most striking omission in the lighting of our sea coast has not before been observed. By establishing a powerful light on the southeastern elbow of Nantucket Island, all the vessels that now feel their dubious way around the South shoal... could coast the south shore of the island, and pass between Sancoty Head and Bass rip in a deep safe channel... The establishment of a light-house at Siasconsett would be more generally useful to the commerce of the United States than any other position on the seaboard.

After a survey in 1847 included the discovery of previously uncharted shoals, the superintendent of the Coast Survey recommended a lighthouse. Congress complied with an appropriation for of $12,000 on August 14, 1848. Ten acres of land for the station were purchased from George Myrick for $250.

Sankaty Head Light c. 1880s

Overseeing construction was Benjamin F. Isherwood, who was later chief engineer for the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. Early in the summer of 1849, schooners brought building materials into Nantucket Harbor. From there, the materials were carted to the bluff in Siasconset.

The contractor Cabet King built the 53-foot, conical tower and accompanying dwelling for $10,333. The tower was constructed of brick, with a 5-foot- deep foundation below the earth. The top 6 feet of the tower were constructed of granite, and atop the tower a 9-foot- tall cast-iron lantern was installed.

A one-and-one-half-story brick dwelling was built adjacent to the lighthouse, which from its earliest days has been white with a broad red central band.

Additional Congressional appropriations of $6,000 in 1848 and $2,000 in 1850 were needed for the purchase and installation of a second-order Fresnel lens from the firm of Henry-Lepaute in Paris. Benjamin Isherwood traveled to France to purchase the lens, and he oversaw its installation himself. Sankaty Head Light became the first Massachusetts lighthouse with a Fresnel lens, and the first lighthouse in the United States with a Fresnel lens as part of its original equipment.

Heavy weights attached to a clockwork mechanism descended into the tower to rotate the lens, which exhibited a fixed white light with more brilliant flashes at set intervals. The light went into service on February 1, 1850. Three days later, the Nantucket Inquirer reported, “The flashes of light are very brilliant and must be visible at a distance of twenty-five miles.”

The contractor Cabet King built the 53-foot, conical tower and accompanying dwelling for $10,333. The tower was constructed of brick, with a 5-foot- deep foundation below the earth. The top 6 feet of the tower were constructed of granite, and atop the tower a 9-foot- tall cast-iron lantern was installed.

A one-and-one-half-story brick dwelling was built adjacent to the lighthouse, which from its earliest days has been white with a broad red central band.

Additional Congressional appropriations of $6,000 in 1848 and $2,000 in 1850 were needed for the purchase and installation of a second-order Fresnel lens from the firm of Henry-Lepaute in Paris. Benjamin Isherwood traveled to France to purchase the lens, and he oversaw its installation himself. Sankaty Head Light became the first Massachusetts lighthouse with a Fresnel lens, and the first lighthouse in the United States with a Fresnel lens as part of its original equipment.

Heavy weights attached to a clockwork mechanism descended into the tower to rotate the lens, which exhibited a fixed white light with more brilliant flashes at set intervals. The light went into service on February 1, 1850. Three days later, the Nantucket Inquirer reported, “The flashes of light are very brilliant and must be visible at a distance of twenty-five miles.”

There were other claims that the light could be seen at the unlikely distance of 40 miles. Historian Samuel Adams Drake called its flashes "very full, vivid and striking," and reported that fishermen called the light "the blazing star."

Visitors at Sankaty Head circa late 1800s

(Nantucket Historical Association)

The newly formed U.S. Lighthouse Board included an extensive description of the light station in a report in January 1852. The lens and the light’s first keeper, Alexander D. Bunker, a former sea captain, received high praise:

This lens is acknowledged universally, so far as could be ascertained, to be, if not the best light in point of brilliancy and power, greatly superior to all others (except, perhaps, those on the Highlands of Navesink, New Jersey) on the entire coast of the United States.

The present principal light-keeper in charge of this establishment is a most respectable and intelligent retired sea captain, who commanded a merchant ship for twenty-five years, and who knows the importance of his trust, and evinces a most praiseworthy interest in the performance of all his duties.

He is assisted by two persons, who, for want of quarters at the light-house, are compelled to reside at some distance from it, to the detriment of the service. The present keeper took charge of the light on the night it was first lighted without previous knowledge or instruction as to its management, but encountered no other difficulty . . . than that arising from the use of bad oil, which he has frequently had. The two assistants and the keeper take a regular watch during the night, relieving each other every four hours.

This lens is acknowledged universally, so far as could be ascertained, to be, if not the best light in point of brilliancy and power, greatly superior to all others (except, perhaps, those on the Highlands of Navesink, New Jersey) on the entire coast of the United States.

The present principal light-keeper in charge of this establishment is a most respectable and intelligent retired sea captain, who commanded a merchant ship for twenty-five years, and who knows the importance of his trust, and evinces a most praiseworthy interest in the performance of all his duties.

He is assisted by two persons, who, for want of quarters at the light-house, are compelled to reside at some distance from it, to the detriment of the service. The present keeper took charge of the light on the night it was first lighted without previous knowledge or instruction as to its management, but encountered no other difficulty . . . than that arising from the use of bad oil, which he has frequently had. The two assistants and the keeper take a regular watch during the night, relieving each other every four hours.

Bunker was keeper until 1854, when he was put in charge of the newly established Nantucket South Shoals Lightship, over more than 23 miles south of the island. He was succeeded by his former assistant, Samuel G. Swain, who stayed until 1861.

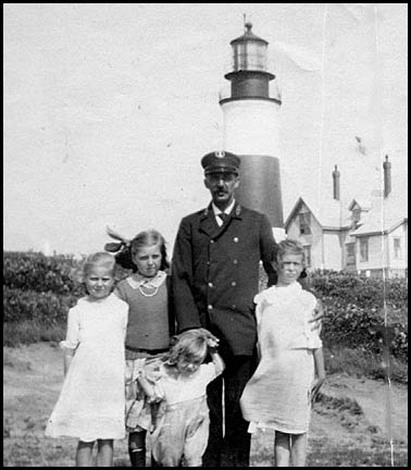

Keeper Eugene Larsen and his children

As Nantucket evolved from whaling capital to vacation resort, the lighthouse became a popular attraction;, with many people climbing climbed to its lantern to enjoy the view and the magnificent lens.

An accommodation was made to the styles of the period, according to the Nantucket Mirror of October 25, 1856: “The narrow aperture on the platform under the lantern at Sankaty lighthouse has been widened to allow ladies with hoop skirts to pass through to see the reflectors.”

George Franklin Folger, who became principal keeper in 1873 after a few years as assistant keeper, had worked in the construction of whaling ships as a young man. He served in the Civil War and was wounded in the second day of the battle at Gettysburg. Folger became the custodian of the Nantucket Athenaeum in his later years.

The 1884 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that new iron stairs had been put in the tower. In 1886, telegraph and telephone lines reached the lighthouse, and a 50-foot pole was added for the display of weather signals. As described in the Lighthouse Board’s annual report of 1888, the “unsightly and dilapidated dwellings” at the station were torn down and replaced by a double wood-frame dwelling. The new house was completed in early 1888 at a cost of $6,700.

Later in 1888, the top part of the tower, the deck, and the lantern were replaced, leaving the tower 70 feet tall. While this work was in progress, the light was exhibited for a few months from a fourth-order lens on a temporary skeleton tower. Some leftover components of the old houses and lantern were sold at public auction.

Calvin Hamblin succeeded Folger as principal keeper in 1882 and stayed until 1891. A 1950 article tells an amusing story of a tiff between Hamblin and an assistant, Benjamin Brown. It seems that Brown was about to go to town without permission. Hamblin told him, “Ben—if you go to town I shall have to log you as leaving the station without giving notice—that you are refusing duty!” The angry but outwardly calm Brown replied, “But, Calvin, I am giving notice—I’m not refusing duty—you can put me down in the log as resigning—here and now!”

An accommodation was made to the styles of the period, according to the Nantucket Mirror of October 25, 1856: “The narrow aperture on the platform under the lantern at Sankaty lighthouse has been widened to allow ladies with hoop skirts to pass through to see the reflectors.”

George Franklin Folger, who became principal keeper in 1873 after a few years as assistant keeper, had worked in the construction of whaling ships as a young man. He served in the Civil War and was wounded in the second day of the battle at Gettysburg. Folger became the custodian of the Nantucket Athenaeum in his later years.

The 1884 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that new iron stairs had been put in the tower. In 1886, telegraph and telephone lines reached the lighthouse, and a 50-foot pole was added for the display of weather signals. As described in the Lighthouse Board’s annual report of 1888, the “unsightly and dilapidated dwellings” at the station were torn down and replaced by a double wood-frame dwelling. The new house was completed in early 1888 at a cost of $6,700.

Later in 1888, the top part of the tower, the deck, and the lantern were replaced, leaving the tower 70 feet tall. While this work was in progress, the light was exhibited for a few months from a fourth-order lens on a temporary skeleton tower. Some leftover components of the old houses and lantern were sold at public auction.

Calvin Hamblin succeeded Folger as principal keeper in 1882 and stayed until 1891. A 1950 article tells an amusing story of a tiff between Hamblin and an assistant, Benjamin Brown. It seems that Brown was about to go to town without permission. Hamblin told him, “Ben—if you go to town I shall have to log you as leaving the station without giving notice—that you are refusing duty!” The angry but outwardly calm Brown replied, “But, Calvin, I am giving notice—I’m not refusing duty—you can put me down in the log as resigning—here and now!”

Joseph Remsen became keeper in 1892, and he remained for 27 years. On a stormy day in January 1892, soon after he became keeper, Remsen spotted a three-masted schooner in trouble on shoals 15 miles to the east.

He telephoned the lifesaving station a few miles away at Coskata. A crew of lifesavers made their way to the vessel, but when night arrived and the men hadn’t returned, townspeople believed they had perished.

Left: Keeper Joseph Remsen and his family. Courtesy of the Nantucket Shipwreck and Lifesaving Museum.

The next morning, the lifesaving crew and the men they had saved from the schooner arrived safely on the beach at Siasconset. They had struggled against the seas for 26 long hours before their return.

An 1898 newspaper article described Remsen’s courteous and informative tours of the lighthouse. "As we reached the foot of the tower," wrote the reporter, "we met another party who were waiting to make the ascent to the top, and I noticed the keeper re-entered the tower with them, and started to retrace his steps up the long, winding stairs without the least sign of resentment on his bronzed and weather-beaten face."

Left: Keeper Joseph Remsen and his family. Courtesy of the Nantucket Shipwreck and Lifesaving Museum.

The next morning, the lifesaving crew and the men they had saved from the schooner arrived safely on the beach at Siasconset. They had struggled against the seas for 26 long hours before their return.

An 1898 newspaper article described Remsen’s courteous and informative tours of the lighthouse. "As we reached the foot of the tower," wrote the reporter, "we met another party who were waiting to make the ascent to the top, and I noticed the keeper re-entered the tower with them, and started to retrace his steps up the long, winding stairs without the least sign of resentment on his bronzed and weather-beaten face."

Seven different assistant keepers served under Remsen, including Charles Vanderhoop, a Gay Head Wampanoag Indian who later became the very popular principal keeper of Gay Head Light on Martha’s Vineyard. Before he returned to his home at Gay Head, Vanderhoop succeeded Remsen as principal keeper at Sankaty Head and served about a year (from April 1919 to May 1920) in that capacity.

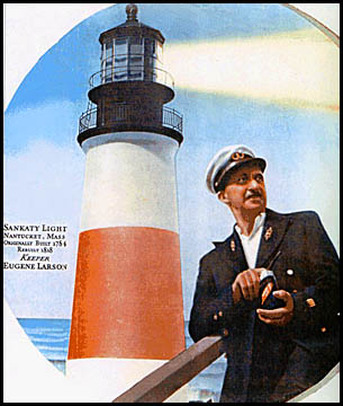

Eugene N. Larsen, a native of Norway who went to sea at 16 and came to America as a young man in 1901, was principal keeper for about 24 years beginning in 1920. Larsen had been an assistant keeper for six years, and he had previously served at the Massachusetts light stations at Minot’s Ledge, Thacher Island, and Graves Ledge. He and his wife, Edvardine, arrived on Nantucket with two children and had five more daughters during their years at the lighthouse.

Larsen's grandson, Renny Stackpole, later remembered being taken into the lighthouse on his birthday by “Papa” Larsen and being placed inside the giant revolving lens.

Several times during his career at Sankaty Head, Larsen won the coveted Lighthouse Pennant, which was awarded for for keeping a clean and orderly station. Larsen also achieved some degree of national fame when his photo was used in a magazine advertisement for the Granger Tobacco Company (right).

An incandescent oil- vapor lamp was installed in 1912, replacing the old wick lamp. The light was converted to electric operation in 1933, and the characteristic was changed to a white flash every 15 seconds.

A modern motor replaced the old clockwork mechanism that turned the lens, and the position of assistant keeper was abolished. In August 1933, the Lighthouse Service Bulletin claimed that the newly electrified light could be seen as far as the Nantucket Shoals Lightship, 41 miles away, although the normal range was only 19 miles.

In April 2019 I received the following email from John Etchingham of Rhode Island, who recalled visiting Sankaty in 1938, when Eugene Larsen was principal keeper.

Was vacationing in ‘Sconset in ‘38. Beach House is where we stayed. It was owned by my grand-aunt Miriam Bulkley. Visited Sankaty that summer. Was met by the Keeper. He took us to the top and back down. I clearly remember him telling us his policy: He was always last up and first down. Safety. (Odd some of the things one remembers.) Anyway it was a fun visit for this six year old.

Larsen's grandson, Renny Stackpole, later remembered being taken into the lighthouse on his birthday by “Papa” Larsen and being placed inside the giant revolving lens.

Several times during his career at Sankaty Head, Larsen won the coveted Lighthouse Pennant, which was awarded for for keeping a clean and orderly station. Larsen also achieved some degree of national fame when his photo was used in a magazine advertisement for the Granger Tobacco Company (right).

An incandescent oil- vapor lamp was installed in 1912, replacing the old wick lamp. The light was converted to electric operation in 1933, and the characteristic was changed to a white flash every 15 seconds.

A modern motor replaced the old clockwork mechanism that turned the lens, and the position of assistant keeper was abolished. In August 1933, the Lighthouse Service Bulletin claimed that the newly electrified light could be seen as far as the Nantucket Shoals Lightship, 41 miles away, although the normal range was only 19 miles.

In April 2019 I received the following email from John Etchingham of Rhode Island, who recalled visiting Sankaty in 1938, when Eugene Larsen was principal keeper.

Was vacationing in ‘Sconset in ‘38. Beach House is where we stayed. It was owned by my grand-aunt Miriam Bulkley. Visited Sankaty that summer. Was met by the Keeper. He took us to the top and back down. I clearly remember him telling us his policy: He was always last up and first down. Safety. (Odd some of the things one remembers.) Anyway it was a fun visit for this six year old.

|

Circa 1940s film of historian Edward Rowe Snow with Keeper Ted Haskins and family. Courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

|

After a century of service, the Fresnel lens was removed in 1950 and was replaced by modern rotating aerobeacons. The old lens can now be seen at the Nantucket Whaling Museum.

Early 1940s aerial view. Courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The person in charge of the installation of the lens at the museum was Renny Stackpole, who many years earlier was given an intimate look at the lens on his birthday.

After Larsen’s retirement, Archford ("Ted") Haskins, previously at Boston Light and Nantucket’s Great Point Light, succeeded Larsen him as keeper in 1944. In his 1945 book Famous Lighthouses of New England, Edward Rowe Snow published a letter from Jeannette Haskins, describing her philosophy of lighthouse life:

We have only been at Sankaty Light since August 1944. As yet we are getting acquainted and in the future I may be able to say, “This I liked best of all,” but I think we all left part of our hearts at Great Point.

It is strange how I feel about God too. Living as I have has influenced my belief. We have never had a chance to attend church regularly but when I look at all the beautiful things of nature I feel my religion lies there. I feel that such a service as the lighthouse has something to do with God. When men are lost at sea most of them pray for light and when the light is seen it might be a beacon guiding these men back to shore and life. When I light the light (which I do sometimes) I feel as if I am believing and helping God.

After Larsen’s retirement, Archford ("Ted") Haskins, previously at Boston Light and Nantucket’s Great Point Light, succeeded Larsen him as keeper in 1944. In his 1945 book Famous Lighthouses of New England, Edward Rowe Snow published a letter from Jeannette Haskins, describing her philosophy of lighthouse life:

We have only been at Sankaty Light since August 1944. As yet we are getting acquainted and in the future I may be able to say, “This I liked best of all,” but I think we all left part of our hearts at Great Point.

It is strange how I feel about God too. Living as I have has influenced my belief. We have never had a chance to attend church regularly but when I look at all the beautiful things of nature I feel my religion lies there. I feel that such a service as the lighthouse has something to do with God. When men are lost at sea most of them pray for light and when the light is seen it might be a beacon guiding these men back to shore and life. When I light the light (which I do sometimes) I feel as if I am believing and helping God.

Haskins remained keeper until 1947. In September 1944, not long after he and his family arrived, the "Great Atlantic Hurricane" of 1944 swept the region. Haskins later recalled:

The tower was rocking so badly that the lens could not revolve and huge pieces of the facing fell from it. We had to brace up the inside of the house or it would have blown in. We had to put shutters on some of the windows to be safe. I lost a lot of friends and shipmates that night.

Left: Keeper Ted Haskins circa 1945. Courtesy of Marla Rogers and Jennifer Fitzpatrick.

Haskins wrote a poem about the 1944 hurricane. Here's part of it:

I thought my days were ending

But my light just had to last,

I had to keep it going

Against the stinging blast.

The night was long and fearful

But the tower stood the test

The gale let up at dawning

And I laid down to rest.

The tower was rocking so badly that the lens could not revolve and huge pieces of the facing fell from it. We had to brace up the inside of the house or it would have blown in. We had to put shutters on some of the windows to be safe. I lost a lot of friends and shipmates that night.

Left: Keeper Ted Haskins circa 1945. Courtesy of Marla Rogers and Jennifer Fitzpatrick.

Haskins wrote a poem about the 1944 hurricane. Here's part of it:

I thought my days were ending

But my light just had to last,

I had to keep it going

Against the stinging blast.

The night was long and fearful

But the tower stood the test

The gale let up at dawning

And I laid down to rest.

In its last years before automation, the station was staffed by a succession of Coast Guard crews. In 1953, the double keeper’s house was razed and replaced by nondescript ranch-style housing. The light was automated in 1965, but Coast Guard personnel continued to occupy the house until 1992.

According to Joseph A. Citro's book, Passing Strange: True Tales of New England Hauntings and Horrors, Coast Guard personnel at Sankaty Head reported a variety of strange events, including pots and pans that would fly on their own. The ghost or whatever was responsible would always stop the activity when asked.

James Deo was one of the Coast Guard keepers from 1963 to 1969. In correspondence in 2010, Deo's daughter, Donna, recalled that some visitors to the lighthouse would make a wish and toss money near the tower. Donna and her brother would pick up all the change at the end of the day.

According to Joseph A. Citro's book, Passing Strange: True Tales of New England Hauntings and Horrors, Coast Guard personnel at Sankaty Head reported a variety of strange events, including pots and pans that would fly on their own. The ghost or whatever was responsible would always stop the activity when asked.

James Deo was one of the Coast Guard keepers from 1963 to 1969. In correspondence in 2010, Deo's daughter, Donna, recalled that some visitors to the lighthouse would make a wish and toss money near the tower. Donna and her brother would pick up all the change at the end of the day.

The Coast Guard removed the lantern in 1969, leaving the automated, rotating aerobeacons "naked" and exposed to the elements. Residents and visitors to Nantucket complained until a new aluminum lantern, somewhat similar in appearance to the old one, was installed.

The spiral stairs inside the tower

In 1990, the Army Corps of Engineers estimated that Sankaty Head Light would be in danger of falling over the eroding bluff within ten years. A move was estimated at $840,000. Concerned islanders formed Save Our Sankaty, a non-profit organization, to raise funds toward the tower's move. Erosion control measures utilizing arrays of pipes and pumps under the sand have been successful in recent years, delaying the inevitable move or extinction of the lighthouse.

The Coast Guard housing and other buildings were eventually moved from the eroding bluff, leaving the lighthouse standing alone.

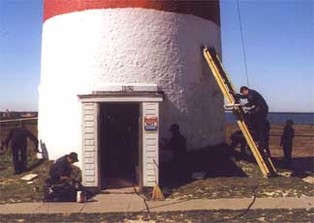

In the fall of 2005, the 'Sconset Trust announced that it was working with the Nantucket Historical Association to gain ownership of the lighthouse, with the goal of having it relocated it to safer ground. Preparations for the historic move began in September 2007, and ownership was transferred to the Sconset Trust in the following month.

The Coast Guard housing and other buildings were eventually moved from the eroding bluff, leaving the lighthouse standing alone.

In the fall of 2005, the 'Sconset Trust announced that it was working with the Nantucket Historical Association to gain ownership of the lighthouse, with the goal of having it relocated it to safer ground. Preparations for the historic move began in September 2007, and ownership was transferred to the Sconset Trust in the following month.

The move was completed in the fall of 2007, and the lighthouse was relighted in its new location by the end of November. The new location is next to the fifth hole of the Sankaty Head Golf Course, 390 feet to the northwest and 250 feet from the bluff's edge.

Sankaty Head, in the village of Siasconset, can be easily be reached from the ferry terminal on Nantucket by car or bicycle, and the lighthouse is also included in some guided tours of the island. The tower is not open to the public, but the grounds are open every day.

For more information about the preservation of Sankaty Head Light, contact:

The 'Sconset Trust

P.O. Box 821

Siasconset, MA 02564

Phone: (508) 228-9917

For more information about the preservation of Sankaty Head Light, contact:

The 'Sconset Trust

P.O. Box 821

Siasconset, MA 02564

Phone: (508) 228-9917

Rob Benchley, an accomplished photojournalist, is now the modern day keeper of Sankaty Head Lighthouse for the 'Sconset Trust. Use the player below to hear an interview with him in episode 81 of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, "Light Hearted."

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Alexander D. Bunker (1850-1854); Samuel G. Swain (assistant 1850-1854, principal keeper 1854-1861); Henry Winslow (assistant 1855-1861, principal keeper 1861-1867); Uriah C. Clark (assistant 1861-1867, principal keeper 1867-1873); George Coggersall (assistant 1867); George F. Folger (assistant 1867-1873, principal keeper 1873-1882); Benjamin C. Sayer (assistant 1868-1872); Charles B. Swain (assistant 1872-1873); Franklin Murphy (assistant 1873-1876); John M. Lamb (assistant, 1876-1897); Simeon Lewis (assistant 1877-1878); William H. Gibbs (assistant 1878-1880); Benjamin F. Myer (assistant 1880); Calvin C. Hamblin (1882-1891); Benjamin F. Brown (assistant, 1882); Wallace A. Eldredge (assistant 1883-1908); James H. Norcross (assistant c. 1889); Ethan Allen (1891-1892); Joseph Remsen (1892-1919); George H. Purdy (assistant, 1909-1912); Charles Vanderhoop (assistant 1912-1913, principal keeper 1919-1920); Carl Delano Hill (assistant c. 1912-1915); C. A. Ellis (assistant, 1920-1921); James Dolby (assistant, 1925-1933); Eugene Larsen (assistant 1914-1920; principal keeper 1920-1944); Francis Macy (first assistant, 1920-1921), Archford Haskins (1944-1947); James Deo (Coast Guard assistant, 1963-1969); James H. Clark (Coast Guard, c. early 1970s)

Other assistants: Freeman Atkins (?), Charles Pollard (?), Marcus E. Howes (?), Thomas J. Kelly (?)

Alexander D. Bunker (1850-1854); Samuel G. Swain (assistant 1850-1854, principal keeper 1854-1861); Henry Winslow (assistant 1855-1861, principal keeper 1861-1867); Uriah C. Clark (assistant 1861-1867, principal keeper 1867-1873); George Coggersall (assistant 1867); George F. Folger (assistant 1867-1873, principal keeper 1873-1882); Benjamin C. Sayer (assistant 1868-1872); Charles B. Swain (assistant 1872-1873); Franklin Murphy (assistant 1873-1876); John M. Lamb (assistant, 1876-1897); Simeon Lewis (assistant 1877-1878); William H. Gibbs (assistant 1878-1880); Benjamin F. Myer (assistant 1880); Calvin C. Hamblin (1882-1891); Benjamin F. Brown (assistant, 1882); Wallace A. Eldredge (assistant 1883-1908); James H. Norcross (assistant c. 1889); Ethan Allen (1891-1892); Joseph Remsen (1892-1919); George H. Purdy (assistant, 1909-1912); Charles Vanderhoop (assistant 1912-1913, principal keeper 1919-1920); Carl Delano Hill (assistant c. 1912-1915); C. A. Ellis (assistant, 1920-1921); James Dolby (assistant, 1925-1933); Eugene Larsen (assistant 1914-1920; principal keeper 1920-1944); Francis Macy (first assistant, 1920-1921), Archford Haskins (1944-1947); James Deo (Coast Guard assistant, 1963-1969); James H. Clark (Coast Guard, c. early 1970s)

Other assistants: Freeman Atkins (?), Charles Pollard (?), Marcus E. Howes (?), Thomas J. Kelly (?)