History of Sandy Neck Light, Barnstable, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

The eastern tip of Sandy Neck—a half-mile wide, six-mile long, dune-studded peninsula on the north side of Cape Cod—marks the entrance to Barnstable Harbor as well as the approach to the small harbor at Yarmouthport.

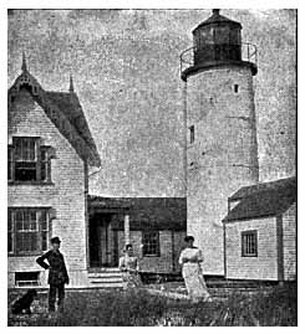

From A Trip Around Cape Cod, 1898

Both developed as important ports for fishing, whaling, and coastal trade in the nineteenth century. In the days when shore whaling was a major local industry, Sandy Neck was the site of try works for the processing of whale blubber. Cranberry harvesting later became the peninsula’s chief business. Today, it’s home to a little cottage community just west of the lighthouse.

Congress appropriated $3,500 for a lighthouse at the eastern tip of the peninsula, a site known as Beach Point, on May 18, 1826. Two acres for the light station were acquired from the town of Barnstable for one dollar, and construction quickly followed. The light went into service on October 1, 1826, and the first keeper -- at a yearly salary of $350 -- was Joseph Nickerson, who stayed for seven years.

Congress appropriated $3,500 for a lighthouse at the eastern tip of the peninsula, a site known as Beach Point, on May 18, 1826. Two acres for the light station were acquired from the town of Barnstable for one dollar, and construction quickly followed. The light went into service on October 1, 1826, and the first keeper -- at a yearly salary of $350 -- was Joseph Nickerson, who stayed for seven years.

The first lighthouse consisted of a wooden lantern on the roof of a brick keeper's house. The lantern originally held 10 lamps and reflectors, exhibiting a fixed white light 40 feet above mean high water and visible for nine nautical miles.

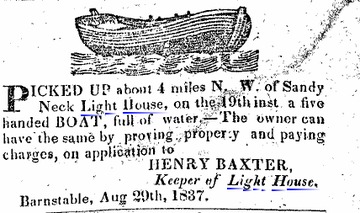

Henry Baxter replaced Nickerson as keeper in early December 1833. He remained until 1844, when he was succeeded by his son, James. Henry Baxter’s first entry in the station’s log read:

This day moved my famerly [sic] and took possession of the lighthouse at Beach Point, Sandineck. Wind NE, Thick weather.

During his stay, Baxter frequently noted severe cold and ice in the harbor, as well as erosion that ate away at the land surrounding the lighthouse. A storm in late October 1837 took six feet of land away on the station’s east side. On December 15, 1834, Baxter wrote:

This day a heavy gale from the SW with snow. Came on shore the schooner Enterprise . . . and Capt. Sawyer with two women on board. Got them on shore with much trouble. Capt. Sawyer much frost bit. So ends very cold and the ice making fast the schooner, laying in the barr [sic] with much ice on her and sails much torn.

This day moved my famerly [sic] and took possession of the lighthouse at Beach Point, Sandineck. Wind NE, Thick weather.

During his stay, Baxter frequently noted severe cold and ice in the harbor, as well as erosion that ate away at the land surrounding the lighthouse. A storm in late October 1837 took six feet of land away on the station’s east side. On December 15, 1834, Baxter wrote:

This day a heavy gale from the SW with snow. Came on shore the schooner Enterprise . . . and Capt. Sawyer with two women on board. Got them on shore with much trouble. Capt. Sawyer much frost bit. So ends very cold and the ice making fast the schooner, laying in the barr [sic] with much ice on her and sails much torn.

In his 1838 inspection report, Lt. Edward D. Carpender recommended the suppression of four of the lamps:

It cannot be that this light requires more lamps than either of the Plymouth [lights]. Those lights are far outside of this, more exposed, and with a vastly heavier trade dependent upon them.

When the engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station in 1842, the number of lamps had been reduced to six. Lewis proclaimed the light "very necessary and useful," largely because it helped mariners avoid the dangerous bar that extended from Sandy Neck. But he found the lighting apparatus "worn out and dirty" and proclaimed the whole building "another specimen of contract work where the Government have been losers by the operation; the whole construction and materials being equally defective." A wooden bulkhead was under construction to protect the station from the encroaching sea, but Lewis saw the structure as "merely a temporary expedient."

Thomas P. D. Baxter was keeper from 1846 to 1862. In his 1946 book, A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow described a visit with Baxter’s grandson, Harry Ryder, of Barnstable. Ryder said that his grandfather frequently had visitors at the lighthouse, and that the packet boat traveling between Boston and Provincetown often stopped there.

An 1850 inspection report reveals that the lantern had been raised some 8 or 10 feet, and a new system of seven lamps and 14-inch reflectors was in use. The inspection found everything in good order under Keeper Thomas Baxter, and it noted that erosion had washed away a considerable amount of the sandy shore near the lighthouse.

The original lighthouse was replaced in 1857 by the 48-foot brick tower that still stands, slightly north of the first light's location. The distinctive pair of iron hoops and six staves that surround the central part of the lighthouse were added in 1887 as part of an effort to shore up cracks in the tower.

The waters inside Sandy Neck were often plagued by ice in winter. One cold day, Keeper Thomas Baxter was heading to Barnstable in his dory, alternately rowing, pulling, and pushing the vessel through the icy harbor. He caught his leg between the dory and the ice, suffering an injury that led to gangrene and eventually his death in 1862.

The original lighthouse was replaced in 1857 by the 48-foot brick tower that still stands, slightly north of the first light's location. The distinctive pair of iron hoops and six staves that surround the central part of the lighthouse were added in 1887 as part of an effort to shore up cracks in the tower.

The waters inside Sandy Neck were often plagued by ice in winter. One cold day, Keeper Thomas Baxter was heading to Barnstable in his dory, alternately rowing, pulling, and pushing the vessel through the icy harbor. He caught his leg between the dory and the ice, suffering an injury that led to gangrene and eventually his death in 1862.

Baxter's wife, Lucy Hinckley Baxter, succeeded him as keeper and raised three children at the station.

The Baxters' grandson Harry Ryder told historian Edward Rowe Snow, "The picture she often described to us of her having to heat the whale oil in the winter months behind the kitchen stove and carry two oil butts up into the tower at midnight is one we never forgot."

Numerous repairs to the original dwelling kept it inhabitable, but the 1880 annual report of the Lighthouse Board deemed the house "beyond repair." The following year's report announced that the old house had been replaced by a new, wood-frame structure, with brick inner walls. The pretty six-room Queen Anne Victorian dwelling still stands.

George A. Jamieson, previously at Minot's Ledge Light and Duxbury Pier Light, became keeper in 1897. After a storm in early December 1898, Jamieson discovered that his chicken coop and 40 chickens were gone, apparently washed away to their doom. As it turned out, the coop had washed safely ashore in Barnstable. The chickens were fine, although they did exhibit some strange symptoms that were attributed to seasickness. Keeper Jamieson's children were schooled by a teacher named Mr. Ferguson, who boarded with the family during the school year. Lessons were held in the small workroom attached to the lighthouse tower, and one of the children later remembered how the teacher's voice would echo inside the tower. The Jamieson children also had fun being pulled around the grounds by their Saint. Bernard dog -- they'd hitch up a cart in summer and a sled in winter, when there was snow.

Numerous repairs to the original dwelling kept it inhabitable, but the 1880 annual report of the Lighthouse Board deemed the house "beyond repair." The following year's report announced that the old house had been replaced by a new, wood-frame structure, with brick inner walls. The pretty six-room Queen Anne Victorian dwelling still stands.

George A. Jamieson, previously at Minot's Ledge Light and Duxbury Pier Light, became keeper in 1897. After a storm in early December 1898, Jamieson discovered that his chicken coop and 40 chickens were gone, apparently washed away to their doom. As it turned out, the coop had washed safely ashore in Barnstable. The chickens were fine, although they did exhibit some strange symptoms that were attributed to seasickness. Keeper Jamieson's children were schooled by a teacher named Mr. Ferguson, who boarded with the family during the school year. Lessons were held in the small workroom attached to the lighthouse tower, and one of the children later remembered how the teacher's voice would echo inside the tower. The Jamieson children also had fun being pulled around the grounds by their Saint. Bernard dog -- they'd hitch up a cart in summer and a sled in winter, when there was snow.

Barnstable Harbor gradually declined in importance, and shifting sands left the lighthouse in a less advantageous position.

Ken Morton at the top of the tower before the replica lantern was installed.

In the summer of 1931, when William L. Anderson was keeper, the lighthouse was decommissioned and its lens was moved to a steel skeleton tower 200 feet closer to the tip of Sandy Neck. The new automated light was fueled by acetylene gas and was operated seasonally, from April 15 to October 15. The light was discontinued in 1952.

The lantern was removed from the lighthouse and the property was sold at auction in 1933 to Warren J. Clear. The price was $711 for 1.93 acres and all the light station buildings. In 1944, the property was sold to Fred Lang, a radio personality on the Yankee Network.

Lang sold the property to the Hinckley family in 1950. Ken Morton and Kee Hinckley today manage the Sandy Neck Lighthouse property for the family.

The lantern was removed from the lighthouse and the property was sold at auction in 1933 to Warren J. Clear. The price was $711 for 1.93 acres and all the light station buildings. In 1944, the property was sold to Fred Lang, a radio personality on the Yankee Network.

Lang sold the property to the Hinckley family in 1950. Ken Morton and Kee Hinckley today manage the Sandy Neck Lighthouse property for the family.

In 2004, Morton began working with the Cape Cod Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation to have a replica lantern installed on the tower in time for its 150th birthday, in 2007, for aesthetic reasons as well as to protect the interior from water damage when it rains or snows.

The lighthouse during its "headless" period

A chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation, the Sandy Neck Restoration Committee, was formed to help restore a lantern on the tower.

The installation of a new lantern began in the spring and summer of 2007. The job was completed in the fall, and in October 2007 the lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation, with a modern LED optic.

Click here to read more about the relighting.

Sandy Neck Light can be seen at a distance from Millway Beach in Barnstable, but it is best seen by boat. Whale watches from Barnstable Harbor provide a view.

The installation of a new lantern began in the spring and summer of 2007. The job was completed in the fall, and in October 2007 the lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation, with a modern LED optic.

Click here to read more about the relighting.

Sandy Neck Light can be seen at a distance from Millway Beach in Barnstable, but it is best seen by boat. Whale watches from Barnstable Harbor provide a view.

Podcast interview with Ken Morton:

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Joseph Nickerson (1826-1833); Henry Baxter (1833-1844); James Baxter (1844-1846); Thomas P. D. Baxter (1846-1862); Lucy Hinckley Baxter (1862-1867); Edward Gorham (1867-1875); Jacob S. Howes (1875-1880); Eunice Crowell Howes (1880-1886); Philip R. Smith (1886-1897); George A. Jamieson (1897-1908); James Jorgensen (1908-1909), Henry L. Pingree (1909-1918); William L. Anderson (c. 1930)

Joseph Nickerson (1826-1833); Henry Baxter (1833-1844); James Baxter (1844-1846); Thomas P. D. Baxter (1846-1862); Lucy Hinckley Baxter (1862-1867); Edward Gorham (1867-1875); Jacob S. Howes (1875-1880); Eunice Crowell Howes (1880-1886); Philip R. Smith (1886-1897); George A. Jamieson (1897-1908); James Jorgensen (1908-1909), Henry L. Pingree (1909-1918); William L. Anderson (c. 1930)