History of Point Gammon Lighthouse, West Yarmouth, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Point Gammon, or Great Point, at the southern end of Great Island, had an interesting history before a lighthouse was established there. In 1796, Dr. James Hedge opened a hospital on the point and conducted early experiments in smallpox inoculation, with some success. The hospital was in operation until 1801.

Point Gammon is just east of the entrance to Lewis Bay and Hyannis Harbor, and a little over two miles north of the dangerous ledges known as Bishops and Clerks.

The point's name comes from an old term used in the game of backgammon. Mariners trying to pass between the point and the offshore ledges were deceived, or "gammoned," which often resulted in disaster.

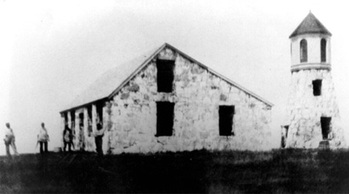

Left: Early photo of Point Gammon Lighthouse and dwelling. Courtesy of Nancy Finco.

The point's name comes from an old term used in the game of backgammon. Mariners trying to pass between the point and the offshore ledges were deceived, or "gammoned," which often resulted in disaster.

Left: Early photo of Point Gammon Lighthouse and dwelling. Courtesy of Nancy Finco.

As the port of Hyannis grew in importance it became obvious that a navigational aid was needed to help mariners negotiate the area. Construction of the light station was swiftly completed and the light went into service on November 21, 1816, with seven lamps and reflectors exhibiting a fixed white light.

The conical tower was built of stone, with a diameter at the base of 16 feet. The walls were 20 feet high, and the tower was topped by an octagonal iron lantern. The one-and-one-half-story dwelling was 16 by 30 feet, with a 10-by-12-foot porch.

The first keeper, Samuel Adams Peak, died in 1824. His teenage son, John, took over at a salary of $350 per year and remained keeper until 1858, when the light was discontinued. This gives Point Gammon the distinction of having only two keepers, both from the same family. John Peak and his wife raised nine children at the lighthouse, two of whom became lighthouse keepers.

The first keeper, Samuel Adams Peak, died in 1824. His teenage son, John, took over at a salary of $350 per year and remained keeper until 1858, when the light was discontinued. This gives Point Gammon the distinction of having only two keepers, both from the same family. John Peak and his wife raised nine children at the lighthouse, two of whom became lighthouse keepers.

In his 1946 book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow wrote about Imogene Peak, one of Keeper John Peak's children:

School for her meant a walk of six miles each way. One of nine Peak children at the light, she said later that the walk of twelve miles daily with other children of the family was beautiful in spring, summer, and fall, but lonely in the winter.

The keeper's house, which was connected to the tower, apparently wasn't very well constructed. The engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited for his important 1843 survey. Lewis found fault with many aspects of the station:

Tower of rubble masonry, to which has been added a superstructure of brick, making the entire height 25 feet; masonry rough-cast outside, but in bad condition; roof soapstone, and leaky; walls leaky; wood work rotten; whole structure out of repair. Dwelling-house of rubble stone, rough-cast outside with gravel and cement; roof shingled; whole structure leaky; wood work decayed, and requires thorough repairing.

John Peak complained that the house was "extremely leaky, particularly on the east side, where the rain leaks in, so that we always have to move our beds during an easterly rain, and also to mop up bucketfuls of water."

In 1855, John Peak counted 4,969 schooners, 1,455 sloops, 216 brigs and four steamboats passing his station. As traffic increased, the lighthouse was considered inadequate, and a lightship was stationed close to the Bishops and Clerks ledges. In 1858, the lightship was replaced by the new Bishops and Clerks Lighthouse. John Peak became the first keeper of the new lighthouse.

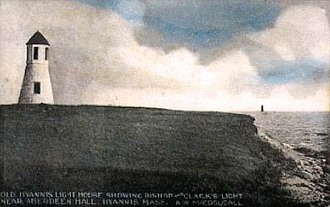

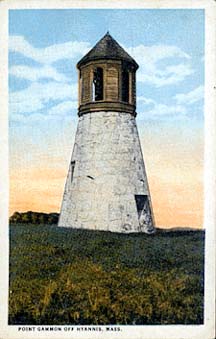

In 1882, Great Island was sold to Charles B. Cory, a wealthy ornithologist from Boston. Cory established the island as a game preserve, with elk, deer, antelopes, pheasants, and other animals. Non-game birds were protected; the island thus became one of the nation's earliest bird sanctuaries. The lighthouse's iron lantern was removed at some point after the light was discontinued. Cory added a taller structure to the top, designed to facilitate the use of the tower as a viewing platform.

Tower of rubble masonry, to which has been added a superstructure of brick, making the entire height 25 feet; masonry rough-cast outside, but in bad condition; roof soapstone, and leaky; walls leaky; wood work rotten; whole structure out of repair. Dwelling-house of rubble stone, rough-cast outside with gravel and cement; roof shingled; whole structure leaky; wood work decayed, and requires thorough repairing.

John Peak complained that the house was "extremely leaky, particularly on the east side, where the rain leaks in, so that we always have to move our beds during an easterly rain, and also to mop up bucketfuls of water."

In 1855, John Peak counted 4,969 schooners, 1,455 sloops, 216 brigs and four steamboats passing his station. As traffic increased, the lighthouse was considered inadequate, and a lightship was stationed close to the Bishops and Clerks ledges. In 1858, the lightship was replaced by the new Bishops and Clerks Lighthouse. John Peak became the first keeper of the new lighthouse.

In 1882, Great Island was sold to Charles B. Cory, a wealthy ornithologist from Boston. Cory established the island as a game preserve, with elk, deer, antelopes, pheasants, and other animals. Non-game birds were protected; the island thus became one of the nation's earliest bird sanctuaries. The lighthouse's iron lantern was removed at some point after the light was discontinued. Cory added a taller structure to the top, designed to facilitate the use of the tower as a viewing platform.

The old stone dwelling was utilized used as a museum for the butterfly collection amassed by Cory and his wife, Harriet.

A view from the top of the lighthouse

Malcolm G. Chace, a banker from Rhode Island who had visited Great Island as a boy, purchased the property in 1914. In the 1930s, the dwelling was dismantled and the stones were used to build a new house on the island. The lighthouse's observatory/lantern installed by Cory has been rebuilt in relatively recent years.

Most of Great Island has remained in the ownership of the Chace family, but they have surrendered development rights for 266 acres through an agreement with the Trustees of Reservations, which ensures it will remain in its natural state.

Great Island, including the lighthouse, is off-limits to the public. The lighthouse can be viewed distantly from the Hyannis-Nantucket ferry, or from excursion boats and fishing charters leaving Hyannis.

Most of Great Island has remained in the ownership of the Chace family, but they have surrendered development rights for 266 acres through an agreement with the Trustees of Reservations, which ensures it will remain in its natural state.

Great Island, including the lighthouse, is off-limits to the public. The lighthouse can be viewed distantly from the Hyannis-Nantucket ferry, or from excursion boats and fishing charters leaving Hyannis.

Keepers: Samuel Peak (1816-1824), John Peak (1824-1858)

Left: A ferry leaving Hyannis passes Point Gammon