History of Race Point Light, Provincetown, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Race Point’s name comes from the strong cross current, known as a “race,” that made navigation around the terminus of Cape Cod a nightmare for mariners. Before the construction of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914, every vessel traveling along the coast between Boston and points south had to negotiate the treacherous bars near here.

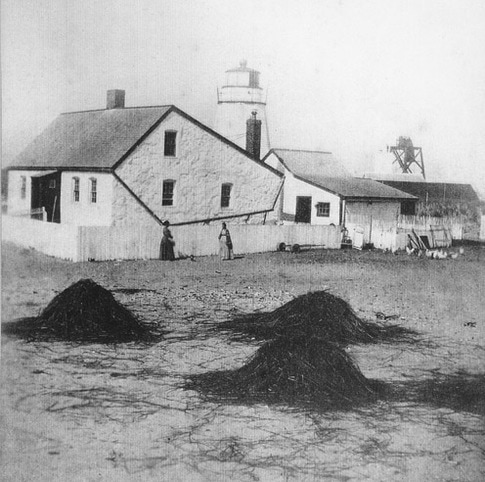

Circa 1859

As early as 1808, the merchants and mariners of Provincetown asked for a lighthouse at Race Point. Funding for a light station was included in a congressional appropriation of $8,000 on April 27, 1816. The original specifications called for an octagonal wooden tower, 20 feet tall, but the plans were soon altered.

A lighthouse at Race Point, Cape Cod’s third light station, went into service on November 5, 1816. The rubblestone tower, laid with “common lime mortar,” was 25 feet tall and its light was 27 feet above mean high water. The tower was joined to a small, stone, one-story keeper’s dwelling via a covered passageway connected to the kitchen.

A Notice to Mariners announced the new light: “It will be a revolving Light, to distinguish it from the one on the Highland of Cape Cod.” It was among the nation’s earliest revolving lights. The wrought iron lantern, six feet four inches high and six feet six inches in diameter, held a system of ten whale oil lamps, each backed by a 13-inch reflector. Each lamp also had a green glass lens that supposedly magnified the light. Although some sources claimed the light was visible as far as 25 miles, that is likely an exaggeration.

This lighting arrangement was designed by Winslow Lewis, a mariner and contractor who patented his system in 1812 and eventually won the exclusive contract to outfit all American lighthouses with his lighting apparatus. He based his system on the lighting system that was then in use in Great Britain.

A lighthouse at Race Point, Cape Cod’s third light station, went into service on November 5, 1816. The rubblestone tower, laid with “common lime mortar,” was 25 feet tall and its light was 27 feet above mean high water. The tower was joined to a small, stone, one-story keeper’s dwelling via a covered passageway connected to the kitchen.

A Notice to Mariners announced the new light: “It will be a revolving Light, to distinguish it from the one on the Highland of Cape Cod.” It was among the nation’s earliest revolving lights. The wrought iron lantern, six feet four inches high and six feet six inches in diameter, held a system of ten whale oil lamps, each backed by a 13-inch reflector. Each lamp also had a green glass lens that supposedly magnified the light. Although some sources claimed the light was visible as far as 25 miles, that is likely an exaggeration.

This lighting arrangement was designed by Winslow Lewis, a mariner and contractor who patented his system in 1812 and eventually won the exclusive contract to outfit all American lighthouses with his lighting apparatus. He based his system on the lighting system that was then in use in Great Britain.

Around this time, a sizeable fishing community and a saltworks grew up around nearby Herring Cove. The little community, known as “Helltown,” was even declared a separate school district in the 1830s. The settlement dwindled later in the nineteenth century.

The second Race Point Light, c. 1890s

Joshua Dyer, a native of Truro on Cape Cod, was the first keeper at Race Point. He died at the age of 37 in November 1822 and was succeeded by his brother, Elijah Dyer, who remained until 1847.

A tremendous storm swept Cape Cod in October 1841. Provincetown's neighbor, Truro, lost seven vessels and 57 men in the storm. Only two crews from Truro survived. Captain Matthias Rich spent 12 hours lashed to the wheel and managed to bring his schooner Water Witch into Herring Cove near Race Point.

I.W.P. Lewis inspected Race Point Light in 1842. He recognized the light's importance, but found reason to be critical:

The light is useful to all vessels leaving Boston, and bound to the eastward, or round the cape, through the South channel; and also as a point of departure for Provincetown harbor, as well as Boston. Its illuminating power is, however, so weak that when a fleet of fishermen are anchored in Herring cove, close by, a stranger would hardly be able to distinguish it from the lights set on board these vessels. A reciprocating light of one good lamp and suitable reflector would be much more efficient than the present apparatus with ten lamps.

The original lighting system had been devised by I.W.P. Lewis' uncle, Winslow Lewis. The younger Lewis also reported that the tower was leaky and had no foundation. The keeper's house, he said, was "in very good repair, and most neatly kept."

A fog bell was installed in 1852. Then, three years later, a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old multiple lamps and reflectors.

The 1863 annual report of the Lighthouse Board detailed plenty of activity:

[T]ower partly taken down and rebuilt, new lantern provided, woodwork renewed, kitchen lathed, plastered and newly floored, roofs repaired, chimneys partly rebuilt, grounds graded, &c., fog-bell removed to a position near the dwelling.

In 1873, the bell was replaced by a steam-driven fog signal housed in a new wood-frame building. With the added duties of tending the fog signal equipment, a second dwelling was built for an assistant keeper in 1874.

It was reported in 1875 that the original lime mortar in the tower had disappeared and the lighthouse had been covered with shingles in an attempt to stop leaks. The shingles and the wooden stairs inside were rotten and the tower needed rebuilding.

A tremendous storm swept Cape Cod in October 1841. Provincetown's neighbor, Truro, lost seven vessels and 57 men in the storm. Only two crews from Truro survived. Captain Matthias Rich spent 12 hours lashed to the wheel and managed to bring his schooner Water Witch into Herring Cove near Race Point.

I.W.P. Lewis inspected Race Point Light in 1842. He recognized the light's importance, but found reason to be critical:

The light is useful to all vessels leaving Boston, and bound to the eastward, or round the cape, through the South channel; and also as a point of departure for Provincetown harbor, as well as Boston. Its illuminating power is, however, so weak that when a fleet of fishermen are anchored in Herring cove, close by, a stranger would hardly be able to distinguish it from the lights set on board these vessels. A reciprocating light of one good lamp and suitable reflector would be much more efficient than the present apparatus with ten lamps.

The original lighting system had been devised by I.W.P. Lewis' uncle, Winslow Lewis. The younger Lewis also reported that the tower was leaky and had no foundation. The keeper's house, he said, was "in very good repair, and most neatly kept."

A fog bell was installed in 1852. Then, three years later, a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old multiple lamps and reflectors.

The 1863 annual report of the Lighthouse Board detailed plenty of activity:

[T]ower partly taken down and rebuilt, new lantern provided, woodwork renewed, kitchen lathed, plastered and newly floored, roofs repaired, chimneys partly rebuilt, grounds graded, &c., fog-bell removed to a position near the dwelling.

In 1873, the bell was replaced by a steam-driven fog signal housed in a new wood-frame building. With the added duties of tending the fog signal equipment, a second dwelling was built for an assistant keeper in 1874.

It was reported in 1875 that the original lime mortar in the tower had disappeared and the lighthouse had been covered with shingles in an attempt to stop leaks. The shingles and the wooden stairs inside were rotten and the tower needed rebuilding.

The needed funds were appropriated and, in 1876, a 45-foot, brick-lined, cast-iron lighthouse replaced the old stone tower at a cost of $2,800. The Fresnel lens was moved to the new tower and the characteristic was changed from a flash to a fixed light.

From A Trip to Cape Cod, 1898

The original keeper’s house was torn down around the same time, and a new dwelling was built. A new rainwater cistern was added in 1877.

James Cashman, who had been wounded in Virginia during the Civil War, served as keeper from 1870 to 1885. He was removed from the position after inspections indicated neglect of his duties.

In 1934, the New Bedford Standard-Times published an article on the station and its three keepers. William H. Lowther had been the principal keeper since 1915. Lowther had entered the Lighthouse Service as a crewman on the tender Mayflower in 1906, and before coming to Cape Cod he had been stationed at Thacher Island off Cape Ann and the Narrows Light in Boston Harbor. Lowther lived at the station with his wife and their young son, Gerald. Gerald Lowther later recalled his arduous walk of more than two miles on the beach to school each day.

Lowther and his wife lived in Provincetown after retirement. In a 1936 article, Mrs. Lowther said that she saw many wrecks in her years at lighthouses, but there was one that especially affected her at Race Point. “Two men were drowned,” she recalled. “I saw everything: the appeals of the men and the shouting and the screeching of the men at the light was so terrible it was in my ears for weeks afterward. I had to go away from the light for a week.”

The first assistant keeper at the time of the 1934 article was the Barnstable native James W. Hinckley, who had been at Race Point since 1920. The historian Edward Rowe Snow wrote that Hinckley often carried 15 pounds of groceries from town across the long stretch of soft sand to the light station. He eventually took to riding a horse back and forth to town. In the 1930s, after he succeeded Lowther as principal keeper, Hinckley made the trip much quicker by customizing a Ford into an early dune buggy. The trip that had taken 75 minutes on horseback was shortened to 30 minutes.

James Cashman, who had been wounded in Virginia during the Civil War, served as keeper from 1870 to 1885. He was removed from the position after inspections indicated neglect of his duties.

In 1934, the New Bedford Standard-Times published an article on the station and its three keepers. William H. Lowther had been the principal keeper since 1915. Lowther had entered the Lighthouse Service as a crewman on the tender Mayflower in 1906, and before coming to Cape Cod he had been stationed at Thacher Island off Cape Ann and the Narrows Light in Boston Harbor. Lowther lived at the station with his wife and their young son, Gerald. Gerald Lowther later recalled his arduous walk of more than two miles on the beach to school each day.

Lowther and his wife lived in Provincetown after retirement. In a 1936 article, Mrs. Lowther said that she saw many wrecks in her years at lighthouses, but there was one that especially affected her at Race Point. “Two men were drowned,” she recalled. “I saw everything: the appeals of the men and the shouting and the screeching of the men at the light was so terrible it was in my ears for weeks afterward. I had to go away from the light for a week.”

The first assistant keeper at the time of the 1934 article was the Barnstable native James W. Hinckley, who had been at Race Point since 1920. The historian Edward Rowe Snow wrote that Hinckley often carried 15 pounds of groceries from town across the long stretch of soft sand to the light station. He eventually took to riding a horse back and forth to town. In the 1930s, after he succeeded Lowther as principal keeper, Hinckley made the trip much quicker by customizing a Ford into an early dune buggy. The trip that had taken 75 minutes on horseback was shortened to 30 minutes.

Race Point is one of the windiest places on the coast. Snow quoted Hinckley: “The wind often touches a mile a minute. Some of the gusts will blow you several feet, and it’s hard going. The sand is bad enough, cutting into your skin, but a combination of sand and snow is almost unbearable.”

James W. Hinckley

On the occasion of his retirement on Christmas Day, 1937, at the age of 70, Keeper Hinckley expressed the opinion that the government should pay a pension to lighthouse keeper’s wives, who “do just as much as the men.”

In his 1946 book, A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow described a visit with Keeper Osborne Hallett, who was in charge from 1945 to 1955. Over coffee and crackers, Snow and Hallett discussed the wreck of the Monte Tabor, which had occurred near Race Point on April 9, 1896. The Sicilian bark was carrying a cargo of salt when it ran into a tremendous storm off Cape Cod.

The captain, intending to enter Provincetown Harbor, made a fatal miscalculation and ran right into the Peaked Hill Bars. Surfmen from the local lifesaving stations tried to go to the crew’s aid, but the vessel broke apart. Six crewmen soon drifted in on the bark’s cabin and were rescued.

The next day, an Italian boy from the crew was found hiding in the bushes near the shore. He told his discoverers that he was afraid he would be killed if discovered; that was what happened to shipwreck victims on Cape Cod, he had heard.

In his 1946 book, A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow described a visit with Keeper Osborne Hallett, who was in charge from 1945 to 1955. Over coffee and crackers, Snow and Hallett discussed the wreck of the Monte Tabor, which had occurred near Race Point on April 9, 1896. The Sicilian bark was carrying a cargo of salt when it ran into a tremendous storm off Cape Cod.

The captain, intending to enter Provincetown Harbor, made a fatal miscalculation and ran right into the Peaked Hill Bars. Surfmen from the local lifesaving stations tried to go to the crew’s aid, but the vessel broke apart. Six crewmen soon drifted in on the bark’s cabin and were rescued.

The next day, an Italian boy from the crew was found hiding in the bushes near the shore. He told his discoverers that he was afraid he would be killed if discovered; that was what happened to shipwreck victims on Cape Cod, he had heard.

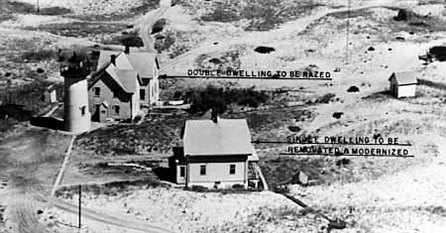

The light was electrified in 1957. Three years later, the larger Gothic Revival keeper's house was torn down and the other house was modernized.

The Coast Guard's officer in charge in the early 1970s was Thomas Branco, who lived at Race Point with his wife, Charlotte, and their five children. With one child in kindergarten and the others in older grades, it meant three round trips to town every day. Years later, the Brancos' daughter, Tracy, said that a tour operator often brought visitors to see the lighthouse. "He'd drive up and say, 'This is where you'll see the little savages,'" she recalled.

Right: The captions on this photograph indicate what the Coast Guard planned to do in 1960 (U.S. Coast Guard photo).

Right: The captions on this photograph indicate what the Coast Guard planned to do in 1960 (U.S. Coast Guard photo).

The light was automated in 1972. The Fresnel lens has been removed; there is now a solar powered VRB-25 optic.

In 1995, the surrounding property, including the keeper's house and oil house, was leased to the American Lighthouse Foundation. International Chimney, the same company that has moved three New England lighthouses, repaired the roof of the keeper's house and rebuilt the chimney. Contractor Richard Davidson of Onset did a great deal of work on the interior and exterior.

Volunteers renovated the interior, and the five-bedroom keeper's house opened for overnight stays. The building now has heat, hot water, flush toilets, refrigeration, and a stove. Guests must bring their own bedding and the kitchen is shared with other guests.

Left: The cast-iron spiral stairs inside the tower.

Jim Walker reported a mystery in 1996. An American flag appeared on a temporary flag pole, put there by an unknown benefactor.

The volunteers took the flag in for the winter, then put it out again in spring. It was shredded in a storm, but again, a new flag mysteriously took its place.

Below, left and right: Two bedrooms in the keeper's house.

Volunteers renovated the interior, and the five-bedroom keeper's house opened for overnight stays. The building now has heat, hot water, flush toilets, refrigeration, and a stove. Guests must bring their own bedding and the kitchen is shared with other guests.

Left: The cast-iron spiral stairs inside the tower.

Jim Walker reported a mystery in 1996. An American flag appeared on a temporary flag pole, put there by an unknown benefactor.

The volunteers took the flag in for the winter, then put it out again in spring. It was shredded in a storm, but again, a new flag mysteriously took its place.

Below, left and right: Two bedrooms in the keeper's house.

The Center for Coastal Studies, a marine mammal research and educational group, leased the fog signal building. After a $45,000 renovation, the building was dedicated as their new field station in June 1999. The fog signal building now contains two bedrooms and is available as a weekly rental in summer.

The oil house has also been restored

The Center for Coastal Studies, a marine mammal research and educational group, leased the fog signal building. After a $45,000 renovation, the building was dedicated as their new field station in June 1999. The fog signal building now contains two bedrooms and is available as a weekly rental in summer.

The Cape Cod Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation raised funds for the installation of a solar electrical system for the keeper's house.Completed in October 2003, the system supplemented a diesel engine electrical generating system. On-site demonstrations show schoolchildren and other visitors how solar power can supply electric energy to the average family home.

The Cape Cod Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation raised funds for the installation of a solar electrical system for the keeper's house.Completed in October 2003, the system supplemented a diesel engine electrical generating system. On-site demonstrations show schoolchildren and other visitors how solar power can supply electric energy to the average family home.

You can park at Race Point Beach and walk about 45 minutes (a little over two miles in very soft sand) to the lighthouse.

A view from the top

Sunset at Race Point Beach is one of the Cape's most popular spectacles, and at times humpback whales can be seen from the beach.

For reservations to stay in the keepers house at Race Point call 1-855-722-3959.

For more information:

Race Point Lighthouse

American Lighthouse Foundation

For reservations to stay in the keepers house at Race Point call 1-855-722-3959.

For more information:

Race Point Lighthouse

American Lighthouse Foundation

Click here for an interview with Gary Childs, chairman of the Cape Cod Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation, on the "Light Hearted" podcast:

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Principal keepers

Joshua Dyer (1816-1822); Elijah Dyer (1822-1847); Lemuel (or Samuel) Cook (1847-1853); Waterman Crocker (1853-1861); Josiah Glenn (1861-1870); James Cashman (1870-1885); Thomas V. Mullins (1885-1892); Charles A. Havender (1892-1904); Samuel S. Smith (1904-1907); Roscoe G. Lopaus (1907-1909); Waldo Leighton (1909-1915); William H. Lowther (1915-1935); James W. Hinckley 1935-1937); Javan D. York (1938-1942)

Assistants

Jesse Smith (assistant, 1855-1861 and 1864-1867); Jared Hill (assistant, 1861-1864); David Newcomb (assistant 1867); Thomas E. Merchant (1st assistant 1874-1876); John W. Nickerson (2nd assistant 1874-1875); William L. Baker (2nd assistant 1875-1876, 1st assistant 1876-1880); Herman F. Smith (2nd assistant 1876-1880; 1st assistant 1880-1882); Charles S. Davis (2nd assistant 1880-1881); Thomas V. Mullins (2nd assistant 1881-1882, 1st assistant 1882-1885); Leonard F. Dunham (2nd assistant 1882-1884, 1st assistant 1884-1885); Joseph E. Frates (2nd assistant 1883); Overy H. Brown (2nd assistant 1883-1885, 1st assistant 1885-1886); Alfred Williams (2nd assistant 1885-1886, 1st assistant 1886-1890); Frank Chapman (2nd assistant 1886-1887); Reuben R. Hopkins (2nd assistant 1887-1888); Edward Kelly (2nd assistant 1887); Charles A. Havender (2nd assistant 1888-1892, 1st assistant 1892); John W. Davis (2nd assistant 1891-1892, 1st assistant 1892-1894); Thomas W. Newcomb (second assistant, 1893); Willis Higgins (2nd assistant 1893-1894, 1st assistant 1894-1897); John McKenzie (2nd assistant 1895-1897), 1st assistant 1897-1906); Michael Campbell (2nd assistant 1897-1899); Edward O. Snow (2nd assistant 1899-1902); William M. Reed (2nd assistant 1902-1904); Arthur Manter (2nd assistant 1904); George N. Black (2nd assistant 1906-1907); Waldo Leighton (2nd assistant 1907-1908, 1st assistant 1908-1909); John Dennen (2nd assistant 1908); J.F. Woodward Jr. (2nd assistant 1912-?); Mr. Nelson (2nd assistant 1913) Mr. Kerr (2nd assistant 1913 -1916 and 1916-1917); Mr. Johnson (2nd assistant 1916-1917); George Irving Herbolt (1st assistant 1917); Mr. Cornell (2nd assistant 1917); Johnan Spencer (2nd assistant 1917-1918, 1st assistant 1918-1920); John E. Rogers (1st assistant, 1918); Mr. Collette (2nd assistant 1918-1919); Mr. H. Smith (2nd assistant 1919); Mr. Ed Smith (2nd assistant 1919); Mr. Griffin (1st assistant 1920); James W. Hinckley (2nd assistant 1920, 1st assistant 1920-1935); Javan D. York (2nd assistant 1921-1935; 1st assistant 1935-1938); Mr. Dubois (2nd assistant 1935); Peter Rondeau (2nd assistant 1935-1938, 1st assistant 1938-1941); Ralph L. Sellers (2nd assistant 1938-1941).

U.S. Coast Guard Commanding Officers

Clifton S. Morong (c. mid-1940s); Theodore M. Kosowski (1944); James O’Brien (1944); Joseph L. Collette (1944); Osborne Earle Hallett (1945-1955); Elias J. Martinez (1955-1956); Gottfried Schiffers (1956-1958); Elias J. Martinez (1958-1959); Aubrey T. Griggs (1959-1960); Thomas Branco (coast Guard, c. early 1970s).