History of Halfway Rock Light, near Harpswell, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

It was always there. When I turned my head on my pillow as a child, in my little bedroom under the giant elm, in our sea-captain's house in Penneville, I could see it blinking away out at the head of Casco Bay. The light on the sea. . . . To me it was as certain a thing as the stars coming out, one by one, in the frame of my window. . . . That lighthouse went right with me to the edge of sleep. -- Robert Tristram Coffin,Yankee Coast, 1946.

National Archives

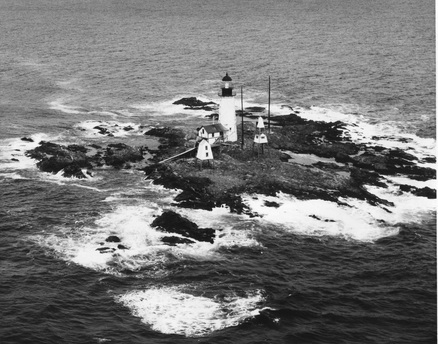

Halfway Rock is a windswept, rocky ledge far out in Casco Bay, about nine miles east of Portland Head. Its name comes from its location about halfway between Cape Elizabeth and Cape Small in Phippsburg. There are several treacherous ledges in the vicinity that have claimed many vessels, including the brig Samuel in the spring of 1835.

The possibility of erecting a lighthouse in the vicinity was discussed as early as the 1830s, but it wasn't until 1869 that $50,000 was appropriated for the building of a stone tower.

Two major storms slowed construction, and work was halted for a time because the funds had run out. After an additional $10,000 was appropriated, the 76-foot granite tower was finished in the summer of 1871.

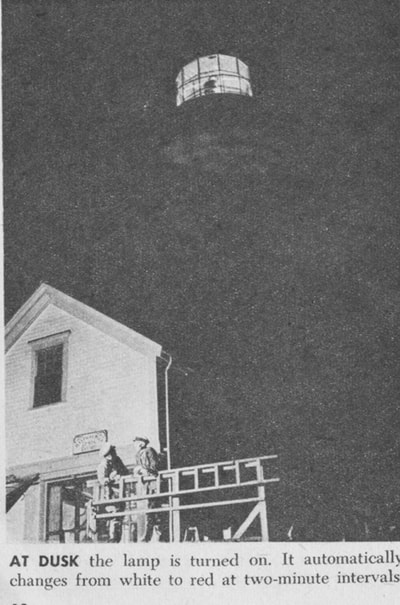

The construction of the tower was very similar to Massachusetts' Minot's Ledge Light, with massive granite blocks dovetailed together. The lighthouse originally held a third-order Fresnel lens, exhibiting a white light punctuated by a red flash every minute.

Halfway Rock's first keeper was Capt. John T. Sterling, a relative of Robert Thayer Sterling, author of the book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them. The keepers lived in rooms inside the tower on the two-acre rocky island, much like the arrangement at Minot's Ledge Light.

The possibility of erecting a lighthouse in the vicinity was discussed as early as the 1830s, but it wasn't until 1869 that $50,000 was appropriated for the building of a stone tower.

Two major storms slowed construction, and work was halted for a time because the funds had run out. After an additional $10,000 was appropriated, the 76-foot granite tower was finished in the summer of 1871.

The construction of the tower was very similar to Massachusetts' Minot's Ledge Light, with massive granite blocks dovetailed together. The lighthouse originally held a third-order Fresnel lens, exhibiting a white light punctuated by a red flash every minute.

Halfway Rock's first keeper was Capt. John T. Sterling, a relative of Robert Thayer Sterling, author of the book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them. The keepers lived in rooms inside the tower on the two-acre rocky island, much like the arrangement at Minot's Ledge Light.

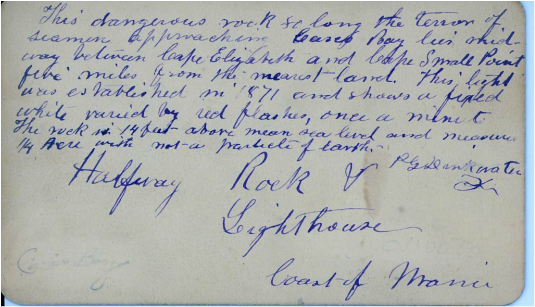

The drawing above was created in 1875 by P.G. Drinkwater, an assistant keeper at Halfway Rock. Above right is what he wrote on the reverse side. Courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

George A. Toothaker, a native of nearby Harpwsell, Maine, spent over 12 years at Halfway Rock as an assistant keeper and principal keeper between 1872 and 1885. "My first day was almost like my last," he told a newspaper reporter. "Me, it affected mentally. Others it affects physically, and I have known of one case where it has driven a man insane."

Toothaker was described in the article as "bronzed and fissured even as the gray and seaweed-stained granite of the Rock itself."

Interviewed long after he had left Halfway Rock, Toothaker said:

Asleep or awake, the beacon haunts you. Often I would start, quick, sharp, out of profound sleep, a great, dark haunting shudder on me -- the light has gone out. Even now it is my fear, and so nervous am I of a night that all sounds startle me, even though it is years since I left the Rock.

The 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses offered this glimpse of life inside Halfway Rock Lighthouse:

Interviewed long after he had left Halfway Rock, Toothaker said:

Asleep or awake, the beacon haunts you. Often I would start, quick, sharp, out of profound sleep, a great, dark haunting shudder on me -- the light has gone out. Even now it is my fear, and so nervous am I of a night that all sounds startle me, even though it is years since I left the Rock.

The 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses offered this glimpse of life inside Halfway Rock Lighthouse:

The first room entered was the kitchen of the establishment. There, every thing looked in the best possible order, with its neat pantry, finely polished cooking stove, and shining utensils. The next flight of stairs brought them to another room, the bedroom of the principal keeper; and above this was a second room, with two beds for the assistant keepers. A fourth flight of stairs brought them out into the watch-room, where the keeper on duty remains all night, to see that the light does not go out, and to keep guard generally. In this room there was a stove, a chair, a table, and a small lamp. It contained also the driving clock, commonly called the 'flash clock,' whose mechanism operated the flash light. for such is the 'characteristic,' as it is called, of the light at Half-way Rock.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

A 43-foot pyramidal skeleton bell tower was bolted to the rock near the lighthouse in 1887, with a 1,000-pound fog bell and striking machinery. A raised walkway connected the bell tower to the lighthouse. Soon after its construction, the bell tower survived a fierce December storm that buried Halfway Rock under eight feet of water.

The fog bell proved inadequate in rough weather, so in 1905 it was replaced by a powerful Daboll trumpet operated by diesel engines.

In 1888, a new boathouse was built with an upper story containing keeper's quarters. This improved the living conditions, but the tower was always the safest place in a storm.

Reaching the mainland for supplies required an 11-mile row to Portland, often made difficult or impossible by rough seas or ice. In February 1934, the keepers reported that ice an inch thick extended all the way past Halfway Rock. Eventually, under the Coast Guard, a buoy tender out of South Portland delivered supplies each week.

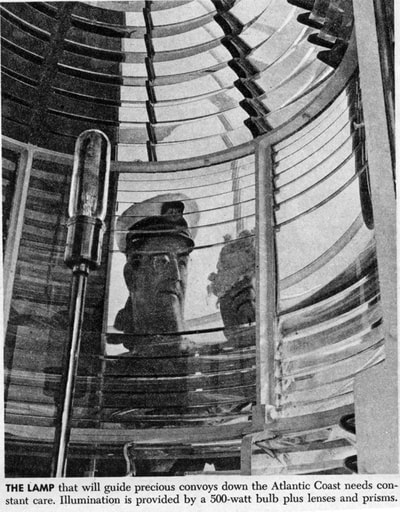

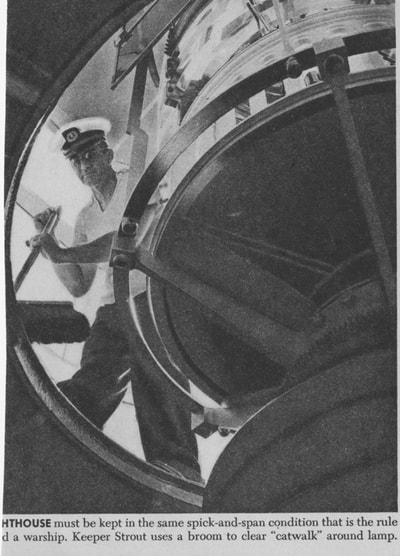

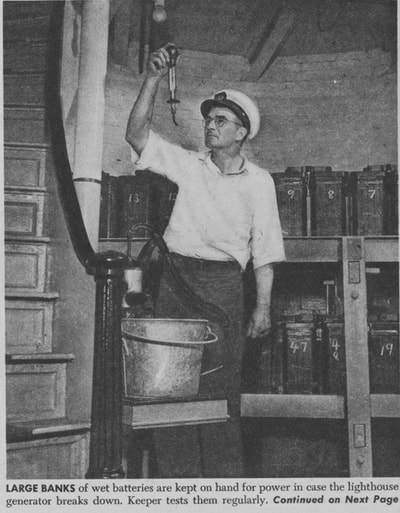

A 1942 article in Parade magazine reported that Halfway Rock Light, unlike most lighthouses on the East Coast, had not been blacked out by World War II. It was eventually turned off a bit later for the remainder of the war, and was returned to service in 1945.

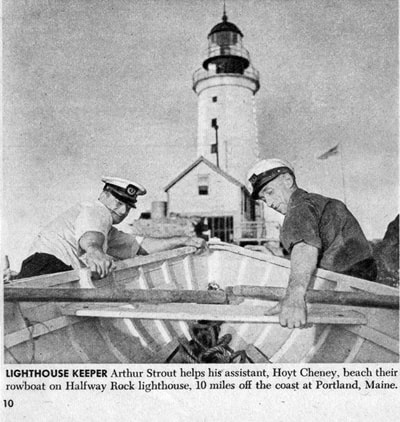

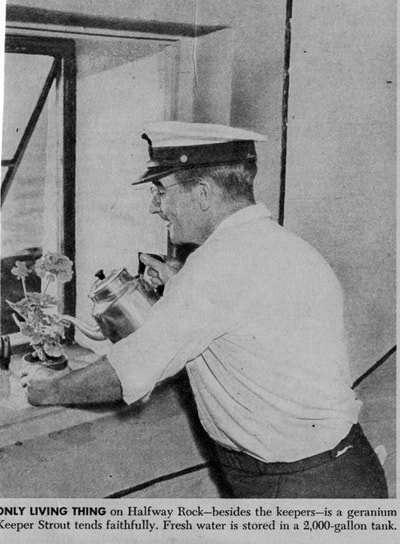

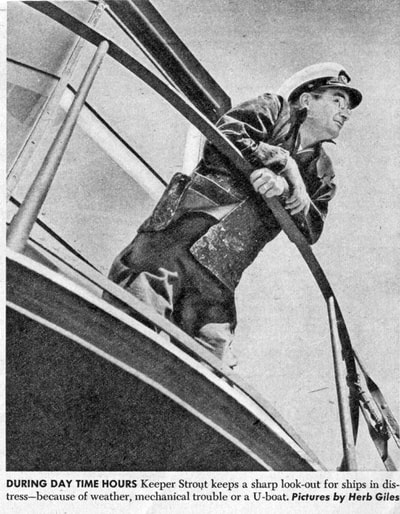

Arthur S. Strout, of the famous Strout family of Maine lighthouse keepers, was the Coast Guard's officer in charge at the time of the 1942 article. Strout spent 17 years in all at Halfway Rock, beginning as a second assistant keeper in 1928. In 1939, when the Coast Guard took over management of lighthouses from the old civilian Lighthouse Service, Strout joined that branch of the service and thus became the first Coast Guard keeper at Halfway Rock. In 1942, the three keepers had eight days of shore leave each month.

The fog bell proved inadequate in rough weather, so in 1905 it was replaced by a powerful Daboll trumpet operated by diesel engines.

In 1888, a new boathouse was built with an upper story containing keeper's quarters. This improved the living conditions, but the tower was always the safest place in a storm.

Reaching the mainland for supplies required an 11-mile row to Portland, often made difficult or impossible by rough seas or ice. In February 1934, the keepers reported that ice an inch thick extended all the way past Halfway Rock. Eventually, under the Coast Guard, a buoy tender out of South Portland delivered supplies each week.

A 1942 article in Parade magazine reported that Halfway Rock Light, unlike most lighthouses on the East Coast, had not been blacked out by World War II. It was eventually turned off a bit later for the remainder of the war, and was returned to service in 1945.

Arthur S. Strout, of the famous Strout family of Maine lighthouse keepers, was the Coast Guard's officer in charge at the time of the 1942 article. Strout spent 17 years in all at Halfway Rock, beginning as a second assistant keeper in 1928. In 1939, when the Coast Guard took over management of lighthouses from the old civilian Lighthouse Service, Strout joined that branch of the service and thus became the first Coast Guard keeper at Halfway Rock. In 1942, the three keepers had eight days of shore leave each month.

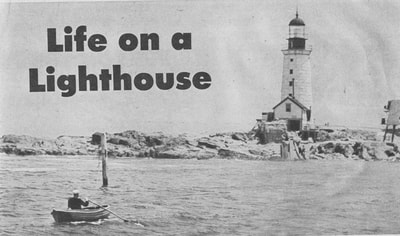

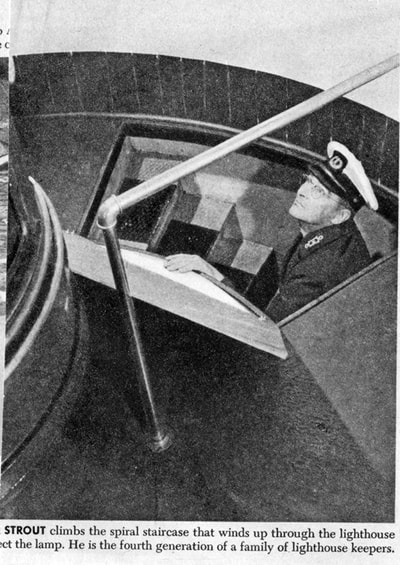

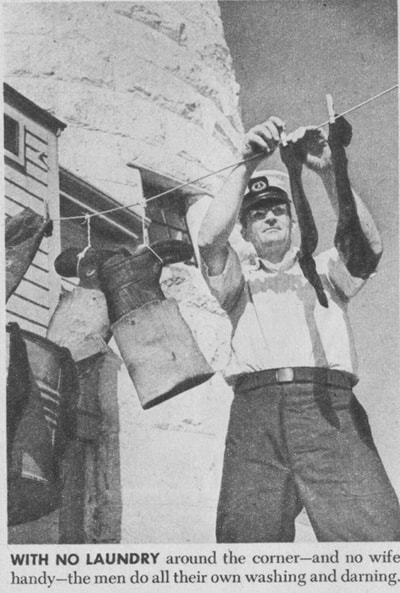

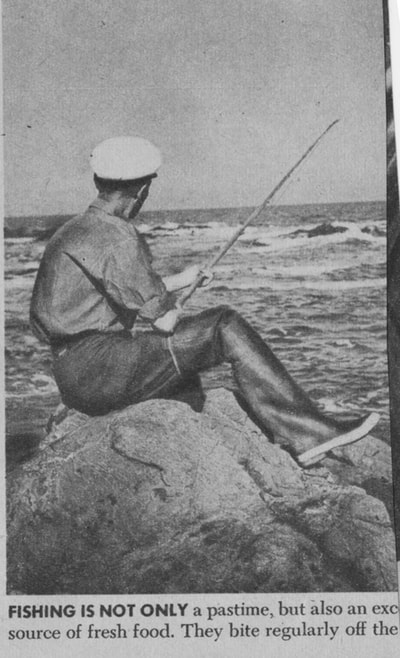

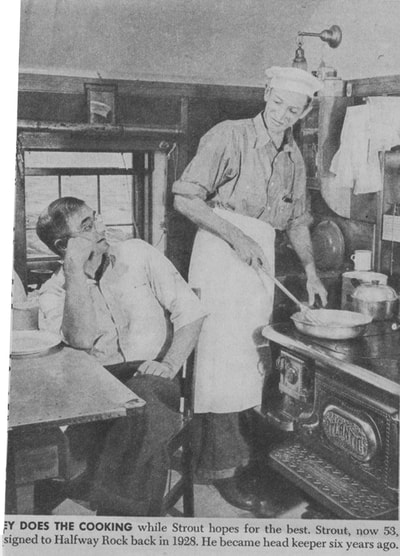

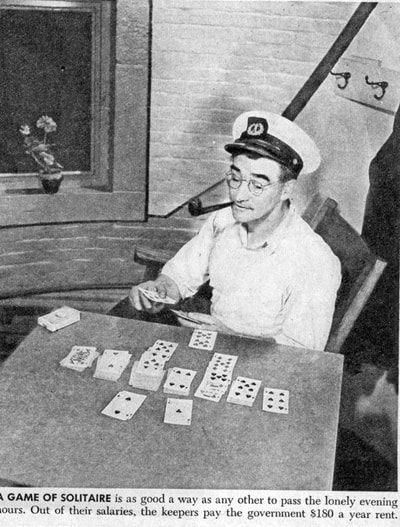

Below: Photos from a 1942 Parade Magazine article, with photos of keepers of Arthur Strout and Hoyt Cheney.

Ken Rouleau of Derry, New Hampshire, was barely out of his teens when he arrived at the Rock in 1960. At that time the small living quarters were inside the upper story of the boathouse, and simply consisted of a bedroom and a kitchen.For a young Coast Guardsman, the isolated station wasn't ideal duty. "We didn't have any fun -- I didn't anyway," Rouleau said in a 2002 interview. "There was not much social life. You took care of yourself."

Ken Rouleau in 2002

The days were split into 12-hour shifts for the two men on the station, so the crewmembers didn't see that much of each other. But some of the men made an impression on Rouleau. He remembered James Murray from Manchester, New Hampshire. And he definitely remembered John Cluff, a native of the southern Maine coast. This may have something to do with the fact that Cluff was a great cook - he made "the most delicious sausage you've ever tasted." His other specialties included asparagus on toast and peach pies.

The Coast Guard sent a large boat to pick the men up or bring them to the station, but it was necessary to transfer to a small peapod boat to land at Halfway Rock. It took great skill to land the boat on the ramp in heavy seas. Rouleau recalled one time when Cluff was returning with the station's television, which had just been repaired on the mainland. The boat flipped over as he tried to land, and Rouleau got a sinking feeling as he watched and thought, "No TV for another three weeks!" Launching the peapod was just as hazardous, as the men would ride it down the steep ramp. "It flipped more than once," said Rouleau.

The Coast Guard sent a large boat to pick the men up or bring them to the station, but it was necessary to transfer to a small peapod boat to land at Halfway Rock. It took great skill to land the boat on the ramp in heavy seas. Rouleau recalled one time when Cluff was returning with the station's television, which had just been repaired on the mainland. The boat flipped over as he tried to land, and Rouleau got a sinking feeling as he watched and thought, "No TV for another three weeks!" Launching the peapod was just as hazardous, as the men would ride it down the steep ramp. "It flipped more than once," said Rouleau.

The Coast Guard crew kept the third-order Fresnel lens and all the brass in the tower spotlessly clean. Every 30 minutes, they checked the clocks associated with the mechanisms that turned the lens.

There were three clockwork mechanisms that had to be wound once a day. The fog signal also had to be operated as needed. "The foghorn would drive you completely bonkers when it would be foggy for seven or eight days at a time," said Rouleau.

Left: The old fog bell tower was still place when this photo was taken in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Ken Rouleau.

Thomas Kuznicki was one of the Coast Guard keepers in the early 1970s. He later wrote:

There is really not a lot one can say about life in a lighthouse, outside of the fact that it is in my opinion the best duty you can have. I was there about 16 months and loved every minute of it, and would have stayed my entire enlistment if I could have. You have to understand my viewpoint.

Left: The old fog bell tower was still place when this photo was taken in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Ken Rouleau.

Thomas Kuznicki was one of the Coast Guard keepers in the early 1970s. He later wrote:

There is really not a lot one can say about life in a lighthouse, outside of the fact that it is in my opinion the best duty you can have. I was there about 16 months and loved every minute of it, and would have stayed my entire enlistment if I could have. You have to understand my viewpoint.

I grew up in Detroit, and trouble was very easy to find in that city -- too many people, not enough work and being young in general. What I found while being stationed on Halfway Rock was peace and quiet (except for the fog signal). For a short time, we fed an injured baby seal we found, until it left. I have very fond memories of Halfway Rock Light station.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

Coast Guardsman Frank Reese was at Halfway Rock during a tremendous storm in February 1972. The 30-foot seas ripped away a fuel tank from the station. Reese was quoted in Edward Rowe Snow's book, Ghosts, Gales, and Gold:

When we lost that fuel tank, we lost everything. You see, everything on the light is electrically operated -- the light, the heat, everything. No fuel, no generator to make electricity. We lost the wood walkway -- that's sort of a porch around the light, and part of the boat ramp . . . I tried the phone several times during the afternoon after we lost our power at 3 p.m., but it was dead. Then, during the evening I picked it up again, mostly because there just wasn't much else to do. This time it worked. I told the base what the situation was and that we were all right, although it was cold.

The crew was soon removed by helicopter until repairs could be completed. One of the last Coast Guard keepers was Lawrence E. Johnson Jr. of Bailey Island. The Coast Guardsmen were supposed to stay three weeks at a time at Halfway Rock, but rough seas often lengthened their stays. When Johnson retired from the Coast Guard, he had to wait a couple of extra weeks for calm seas so he could return to the mainland.

Another of the last keepers was Stephen Krikorian, also a Maine native. Krikorian told the Portland Press Herald about some of the unusual ways the keepers passed the lonely hours. He picked up a basketball that had washed ashore. "There are 2,448 pimples on this. I counted 'em. It took a day." The men kept a chart in the house with the heading "House Fly Killings." Coast Guardsman Ronald Handfield held the record of 257 fly killings in two months.

When we lost that fuel tank, we lost everything. You see, everything on the light is electrically operated -- the light, the heat, everything. No fuel, no generator to make electricity. We lost the wood walkway -- that's sort of a porch around the light, and part of the boat ramp . . . I tried the phone several times during the afternoon after we lost our power at 3 p.m., but it was dead. Then, during the evening I picked it up again, mostly because there just wasn't much else to do. This time it worked. I told the base what the situation was and that we were all right, although it was cold.

The crew was soon removed by helicopter until repairs could be completed. One of the last Coast Guard keepers was Lawrence E. Johnson Jr. of Bailey Island. The Coast Guardsmen were supposed to stay three weeks at a time at Halfway Rock, but rough seas often lengthened their stays. When Johnson retired from the Coast Guard, he had to wait a couple of extra weeks for calm seas so he could return to the mainland.

Another of the last keepers was Stephen Krikorian, also a Maine native. Krikorian told the Portland Press Herald about some of the unusual ways the keepers passed the lonely hours. He picked up a basketball that had washed ashore. "There are 2,448 pimples on this. I counted 'em. It took a day." The men kept a chart in the house with the heading "House Fly Killings." Coast Guardsman Ronald Handfield held the record of 257 fly killings in two months.

In 1975, the keepers were removed for good and the light was automated with a modern DCB 224 optic.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

The original Fresnel lens went to the museum at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. Today the lighthouse tower stands alone on Halfway Rock, still an active aid to navigation. Storms have destroyed the other structures. Most recently, the station's marine railway was destroyed by the "Perfect" storm of October 1991.

Under the Maine Lights Program coordinated by the Island Institute of Rockland, Halfway Rock Light was expected to be turned over to a local nonprofit group or community, but there were no applicants. In May 2000, the American Lighthouse Foundation was licensed by the Coast Guard to care for the tower.

In June 2004, Maine Preservation included this lighthouse on their list of the state's most endangered properties.

Under the Maine Lights Program coordinated by the Island Institute of Rockland, Halfway Rock Light was expected to be turned over to a local nonprofit group or community, but there were no applicants. In May 2000, the American Lighthouse Foundation was licensed by the Coast Guard to care for the tower.

In June 2004, Maine Preservation included this lighthouse on their list of the state's most endangered properties.

Above: boarding a Coast Guard vessel from Halfway Rock on June 5, 2013.

Below, photos from a site visit on June 5, 2013. Click on a thumbnail for a larger image.

The property was made available to a new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act, but there were no applicants. As a result, it was put up for sale via online auction in May 2014. The auction ended in September 2014 with a high bid of $283,000.

In his first year of ownership, the new owner, Ford Reiche, accomplished the rebuilding of the boat landing ramp, and the complete exterior and interior restoration of the attached two-story wooden building. The first year also saw the start of the restoration of the lighthouse tower.

In the summer of 2017, the tower was repointed and the interior was painted by the J.B. Leslie Company. A new roof was also installed on the attached wooden building.

The dramatic lighthouse can be seen distantly from the Portland Observatory and from some of the tour boats out of Portland, but it is best seen by private boat or plane.

You can listen below to an interview with owner Ford Reiche.

In his first year of ownership, the new owner, Ford Reiche, accomplished the rebuilding of the boat landing ramp, and the complete exterior and interior restoration of the attached two-story wooden building. The first year also saw the start of the restoration of the lighthouse tower.

In the summer of 2017, the tower was repointed and the interior was painted by the J.B. Leslie Company. A new roof was also installed on the attached wooden building.

The dramatic lighthouse can be seen distantly from the Portland Observatory and from some of the tour boats out of Portland, but it is best seen by private boat or plane.

You can listen below to an interview with owner Ford Reiche.

Use the player below to hear an interview with former Coast Guard keeper Tim Bailey.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Principal Keepers: John Sterling (1871-1883), George H. Toothacker (Toothaker?) (1883-1885), William T. Holbrook (1885-1890), Charles S. Williams (1890-1891), J. Harmon Stover (1891-1893), Parker O. Haley (1893-1900), Edmond Coffin (1900-1902), John B. Dewyea (1902-1921), Wesley Gray (1921-1934), Arthur S. Strout (c.1936-1939; joined Coast Guard and remained officer in charge until 1945)

Assistant Keepers: James Jones (1871-1872), Albert F. Purrington (1871-1872; 2nd asst, 1874-1881), Sylvanus E. Doyle (1872-1873), H. G. Cook Jr. (1872-1873), P.G. Drinkwater (2nd) (1873), George H. Toothacker (Toothaker?) (1873-1883), William T. Holbrook (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1881-1885), George H. Small (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1883-1885), James W. Sterling (2nd asst., then 1st asst.,1885-1887), Isaac W. Morrison (2nd asst., then 1st asst.,1886-1889), P. A. Dugan (2nd asst., 1887-1888), Eli M. Alexander (1st asst., 1888-1889), J. Harmon Stover (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1889-1891), Edmond Coffin (1889-1900), Oliver P. Burns (2nd asst., 1891), Edward H. Pierce (2nd asst., 1891-1892), John B. Dewyea (2nd asst., 1891-1902), Frank L. Peabbles (2nd asst., 1900-1902), W. S. Adams (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1902-1904), J. L. Dyer (2nd asst., 1902-1904), Giles H. Farley (1st asst., 1904-1907), William Henry Burns (1st asst., 1907-1912), LeRoy S. Elwell (2nd asst., 1904-1907), Harold Hutchins (2nd asst., 1907-1908), Thomas L. Godfrey (2nd asst., 1908), J. C. Morong (2nd asst., 1908-1909), A. S. Rollins (2nd asst., 1909-1910), Eugene W. Osgood (2nd asst., 1910-1912), Roger Paul Philbrick (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1911-1912), A. J. Clinch (2nd asst., 1913), William M. Larrabee (2nd asst., 1913-1914), Fuller E. Larrabee (1st asst., 1913-1916), Wesley Gray (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1914-1921), A. J. Griffin (2nd asst., 1916), William Foster Reed (2nd asst., 1916-1920), N. R. Murphy (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1920-1922), E. W. Murphy (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1921-1926), Martin Sabins (2nd asst., 1922-1923), Augustus S. Kelly (2nd asst., 1923-1926), Bernard A. Small (2nd asst., 1926), E. E. Moore (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1926-1929), A. R. Stevens (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1926-1929), Arthur S. Strout (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1928-1934), C. J. Wheeler (2nd asst., 1929), H. A. Ball (2nd asst., 1929-1932), John L. Pendell (Pennell?) (2nd asst., 1932-?), G. Duffy Brown (2nd asst., 1934-?);

Coast Guard officers in charge: Arthur S. Strout (1939-1945), A. W. McLaughlin (1945), Wilbur Brewster (1945-1948), Louis J. Nagy (1948-1949), Norman Goben (1949), Stephen F. Flood (1949-1950), H. N. Robinson (1950), John P. Sawasha (1950), William L. Lockhart (1950-1951), John L. Mason (1951-1952), James R. Seward (1952), Leon G. Lewis (1952-1953), Forrest S. Cheney (1953-1955), James R. Wilson (1955-1956), Harry L. Cressey (1956-1957), Michael A. Stern (1957-1958), James E. Murray (1958-1961 and 1963-1966), Leon E. Minzy (1961-1962), Horace A. Leverett (c. 1966).

Other Coast Guard personnel: Hoyt Cheney (c. early 1940s); Reuben Kurtti (1947), Julian Hatch (1950-1951), William Yost (c. 1951-1952), Kenneth Rouleau (c. 1960-1961), Robert Shillace ( c. 1966), Edward Hannula (c. 1966), Richard Shuman (Oct. 1969-July 1970); Timothy Bailey (1971-1972) Frank Reese (c. 1972), Lawrence E. Johnson, Jr. (c. 1970s), Thomas Kuznicki (c. early 1970s), Stephen Krikorian (c. 1975), Ronald Handfield (c. 1975), Larry Caron Jr. (c. 1975), Ken Field (c. 1970s)

Principal Keepers: John Sterling (1871-1883), George H. Toothacker (Toothaker?) (1883-1885), William T. Holbrook (1885-1890), Charles S. Williams (1890-1891), J. Harmon Stover (1891-1893), Parker O. Haley (1893-1900), Edmond Coffin (1900-1902), John B. Dewyea (1902-1921), Wesley Gray (1921-1934), Arthur S. Strout (c.1936-1939; joined Coast Guard and remained officer in charge until 1945)

Assistant Keepers: James Jones (1871-1872), Albert F. Purrington (1871-1872; 2nd asst, 1874-1881), Sylvanus E. Doyle (1872-1873), H. G. Cook Jr. (1872-1873), P.G. Drinkwater (2nd) (1873), George H. Toothacker (Toothaker?) (1873-1883), William T. Holbrook (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1881-1885), George H. Small (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1883-1885), James W. Sterling (2nd asst., then 1st asst.,1885-1887), Isaac W. Morrison (2nd asst., then 1st asst.,1886-1889), P. A. Dugan (2nd asst., 1887-1888), Eli M. Alexander (1st asst., 1888-1889), J. Harmon Stover (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1889-1891), Edmond Coffin (1889-1900), Oliver P. Burns (2nd asst., 1891), Edward H. Pierce (2nd asst., 1891-1892), John B. Dewyea (2nd asst., 1891-1902), Frank L. Peabbles (2nd asst., 1900-1902), W. S. Adams (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1902-1904), J. L. Dyer (2nd asst., 1902-1904), Giles H. Farley (1st asst., 1904-1907), William Henry Burns (1st asst., 1907-1912), LeRoy S. Elwell (2nd asst., 1904-1907), Harold Hutchins (2nd asst., 1907-1908), Thomas L. Godfrey (2nd asst., 1908), J. C. Morong (2nd asst., 1908-1909), A. S. Rollins (2nd asst., 1909-1910), Eugene W. Osgood (2nd asst., 1910-1912), Roger Paul Philbrick (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1911-1912), A. J. Clinch (2nd asst., 1913), William M. Larrabee (2nd asst., 1913-1914), Fuller E. Larrabee (1st asst., 1913-1916), Wesley Gray (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1914-1921), A. J. Griffin (2nd asst., 1916), William Foster Reed (2nd asst., 1916-1920), N. R. Murphy (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1920-1922), E. W. Murphy (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1921-1926), Martin Sabins (2nd asst., 1922-1923), Augustus S. Kelly (2nd asst., 1923-1926), Bernard A. Small (2nd asst., 1926), E. E. Moore (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1926-1929), A. R. Stevens (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1926-1929), Arthur S. Strout (2nd asst., then 1st asst., 1928-1934), C. J. Wheeler (2nd asst., 1929), H. A. Ball (2nd asst., 1929-1932), John L. Pendell (Pennell?) (2nd asst., 1932-?), G. Duffy Brown (2nd asst., 1934-?);

Coast Guard officers in charge: Arthur S. Strout (1939-1945), A. W. McLaughlin (1945), Wilbur Brewster (1945-1948), Louis J. Nagy (1948-1949), Norman Goben (1949), Stephen F. Flood (1949-1950), H. N. Robinson (1950), John P. Sawasha (1950), William L. Lockhart (1950-1951), John L. Mason (1951-1952), James R. Seward (1952), Leon G. Lewis (1952-1953), Forrest S. Cheney (1953-1955), James R. Wilson (1955-1956), Harry L. Cressey (1956-1957), Michael A. Stern (1957-1958), James E. Murray (1958-1961 and 1963-1966), Leon E. Minzy (1961-1962), Horace A. Leverett (c. 1966).

Other Coast Guard personnel: Hoyt Cheney (c. early 1940s); Reuben Kurtti (1947), Julian Hatch (1950-1951), William Yost (c. 1951-1952), Kenneth Rouleau (c. 1960-1961), Robert Shillace ( c. 1966), Edward Hannula (c. 1966), Richard Shuman (Oct. 1969-July 1970); Timothy Bailey (1971-1972) Frank Reese (c. 1972), Lawrence E. Johnson, Jr. (c. 1970s), Thomas Kuznicki (c. early 1970s), Stephen Krikorian (c. 1975), Ronald Handfield (c. 1975), Larry Caron Jr. (c. 1975), Ken Field (c. 1970s)