History of Boon Island Lighthouse, York, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Eight or nine miles out, in plain sight, Boon Island lifts its solitary shaft aloft like an 'eternal exclamation mark' to the temerity of its builders. There is no comfortable dwelling on that lonely rock, over which storms sweep unchecked. The tower is itself both house and home to the watchmen of the sea, and in great gales a prison from which there is no escape until the return of fine weather. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

Drawing of the Nottingham Galley shipwreck

In the summer of 1682, a coastal trading vessel, the Increase, was wrecked on the rocky ledges of barren Boon Island, several miles off the southern Maine coast. The four survivors—three white men and one Indian—spent a month on the island, living on fish and gulls’ eggs. One day the men saw smoke rising from Mount Agamenticus several miles away, so they built a fire in response. The Indians at Mount Agamenticus saw the smoke from the island, and the stranded men were soon rescued.

The precise origins of the island’s name are shrouded in four centuries of history. It’s been often stated that the men from the Increase, seeing their survival as a boon granted by God, were moved to name the island Boon. In fact, the island was referred to by that name long before the wreck of the Increase. John Winthrop mentioned it in his journal in 1630:

We saw, also, ahead of us, some four leagues from shore, a small rock, called Boone Isle, not above a flight shot over, which hath a dangerous shoal to the E. and by S. of it, some two leagues in length.

The island was also mentioned five years later in Richard Mather’s journal; like Winthrop, he spelled it “Boone.” Another early variation on the spelling of the island’s name was “Bone,” not inappropriate for a location where so many mariners met their doom.

The precise origins of the island’s name are shrouded in four centuries of history. It’s been often stated that the men from the Increase, seeing their survival as a boon granted by God, were moved to name the island Boon. In fact, the island was referred to by that name long before the wreck of the Increase. John Winthrop mentioned it in his journal in 1630:

We saw, also, ahead of us, some four leagues from shore, a small rock, called Boone Isle, not above a flight shot over, which hath a dangerous shoal to the E. and by S. of it, some two leagues in length.

The island was also mentioned five years later in Richard Mather’s journal; like Winthrop, he spelled it “Boone.” Another early variation on the spelling of the island’s name was “Bone,” not inappropriate for a location where so many mariners met their doom.

According to some writers, including the popular New England historian Edward Rowe Snow, the island’s name stemmed from the practice of local fishermen, who left barrels of provisions on the island for the benefit of shipwrecked sailors. That would certainly have been a “boon” in such circumstances.

In any case, the name is an ironic one for the desolate pile of rocks that the poet Celia Thaxter called "the forlornest place that can be imagined."

The most famous incident in the island's history was the wreck of the British ship Nottingham Galley on December 11, 1710. The survivors struggled to stay alive for over three weeks, finally resorting to cannibalism. The harrowing story was fictionalized by Kenneth Roberts in his novel Boon Island. In recent years cannons have been located in about 25 feet of water that are believed to have been on board the Nottingham Galley.

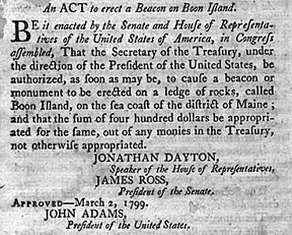

In 1797, General Benjamin Lincoln, local lighthouse superintendent, met with the Boston Marine Society to discuss the building of an unlighted beacon on Boon Island for the safety of local fishermen and coastal traders.Construction began the following July. The first wooden tower as finished in 1799. It survived until 1804, when it was destroyed by a tremendous storm.

A stone day beacon was erected in the summer of 1805. Three of the workers involved in erecting the tower drowned when their boat capsized as they left the island.

The most famous incident in the island's history was the wreck of the British ship Nottingham Galley on December 11, 1710. The survivors struggled to stay alive for over three weeks, finally resorting to cannibalism. The harrowing story was fictionalized by Kenneth Roberts in his novel Boon Island. In recent years cannons have been located in about 25 feet of water that are believed to have been on board the Nottingham Galley.

In 1797, General Benjamin Lincoln, local lighthouse superintendent, met with the Boston Marine Society to discuss the building of an unlighted beacon on Boon Island for the safety of local fishermen and coastal traders.Construction began the following July. The first wooden tower as finished in 1799. It survived until 1804, when it was destroyed by a tremendous storm.

A stone day beacon was erected in the summer of 1805. Three of the workers involved in erecting the tower drowned when their boat capsized as they left the island.

In June 1811, General Lincoln recommended a lighthouse on Boon Island. The tower, completed by that winter, exhibited a fixed light 32 feet above the water. The first keeper, after witnessing the vulnerability of the low island (14 feet above sea level at its highest point ) to storms, left after only a few weeks.

The second keeper, David Oliver, also resigned and was succeeded by Thomas Hanna. Hanna resigned in 1816. The next keeper, former mariner Eliphalet Grover, a York native born in 1778, served a remarkable 22 years at the station. Grover's log resides at the Old York Historical Society. Here is an excerpt, preserving Grover's spelling:

October 31, 1829: At 9 PM all my famely was forst to go to the Lighthouse and Stay until 5 next morning. At our return to the house found all our water gone and all the platforms gone and all my turnips and cabage washt away and my walls all Down. I have been hear 13 years 4 months 28 days and never see such a time before. The sea washd the small rocks from under the Lighthouse and Dwelling house the island was all under water for 4 hours.

Left: This fiddle, now at the York Historical Society, was created at Boon Island by Keeper Eliphalet Grover.

October 31, 1829: At 9 PM all my famely was forst to go to the Lighthouse and Stay until 5 next morning. At our return to the house found all our water gone and all the platforms gone and all my turnips and cabage washt away and my walls all Down. I have been hear 13 years 4 months 28 days and never see such a time before. The sea washd the small rocks from under the Lighthouse and Dwelling house the island was all under water for 4 hours.

Left: This fiddle, now at the York Historical Society, was created at Boon Island by Keeper Eliphalet Grover.

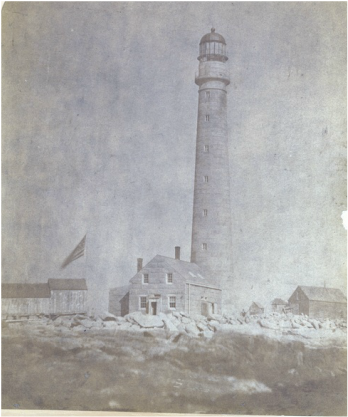

After suffering great damage in storms, the lighthouse was rebuilt in 1831. It was built of rubblestone and stood 49 feet tall, with an octagonal wrought iron lantern. The light was 69 feet above mean high water.

Circa 1859. (National Archives)

Another great storm struck on January 26, 1839. A letter written by Keeper Grover was published in newspapers:

We experienced a heavy gale from the South East: at 10 P.M. the sea was up around the buildings; Sunday morning between the hours of 9 and 11 the sea broke upon the buildings, and the family then retreated to the Light House as a place of safety. The sea broke into the porch (built in front of the house) and unhung the doors and forced the door of the dwelling house and done considerable damage, washing shells and sea weed into the rooms. It washed away the plat-form which was built for the purpose of getting from one building to another. The sea struck the House monument (or wood house) and tore off the shingles half-way to the eaves, washing loose rocks away in front of the buildings, so that it had a fair chance to sweep over. During the day a light breeze sprung up from the S.W. and W. and at 3 P.M. the tide being down, some of the family ventured out and beheld an astonishing spectacle. Fragments of wood were scattered over the Island, and large rocks which had been quiet for more than twenty years were torn from their places. The sea continued rough for three days, but the wind coming from the North West it gradually subsided.

Capt. Nathaniel Baker became keeper in 1846. The schooner Caroline was wrecked on the island in the same year, and Baker rescued the crew. Despite his heroism, Baker was dismissed as keeper in 1849 and replaced by John Thompson, who had been dismissed earlier. In those days lighthouse keeping jobs were frequently given as political favors.

The present lighthouse was constructed in 1854, along with a new dwelling. The stone tower, built of granite supplied by Joseph W. Coburn of Boston, is 133 feet high -- the tallest lighthouse in New England. It is 25 feet in diameter at its base and 12 feet in diameter at the top.

An additional $19,973 was appropriated in 1854 for "procuring illuminating apparatus, and completing the light-house tower and buildings..." The new second-order Fresnel lens went into operation on January 1, 1855.

Poet Celia Thaxter described the lighthouse in her 1873 book, Among the Isles of Shoals:

A slender column against the sky... Sometimes it looms colossal in the mirage of summer; in winter it lies blurred and ghostly at the edge of the chilly sea and pallid sky.

We experienced a heavy gale from the South East: at 10 P.M. the sea was up around the buildings; Sunday morning between the hours of 9 and 11 the sea broke upon the buildings, and the family then retreated to the Light House as a place of safety. The sea broke into the porch (built in front of the house) and unhung the doors and forced the door of the dwelling house and done considerable damage, washing shells and sea weed into the rooms. It washed away the plat-form which was built for the purpose of getting from one building to another. The sea struck the House monument (or wood house) and tore off the shingles half-way to the eaves, washing loose rocks away in front of the buildings, so that it had a fair chance to sweep over. During the day a light breeze sprung up from the S.W. and W. and at 3 P.M. the tide being down, some of the family ventured out and beheld an astonishing spectacle. Fragments of wood were scattered over the Island, and large rocks which had been quiet for more than twenty years were torn from their places. The sea continued rough for three days, but the wind coming from the North West it gradually subsided.

Capt. Nathaniel Baker became keeper in 1846. The schooner Caroline was wrecked on the island in the same year, and Baker rescued the crew. Despite his heroism, Baker was dismissed as keeper in 1849 and replaced by John Thompson, who had been dismissed earlier. In those days lighthouse keeping jobs were frequently given as political favors.

The present lighthouse was constructed in 1854, along with a new dwelling. The stone tower, built of granite supplied by Joseph W. Coburn of Boston, is 133 feet high -- the tallest lighthouse in New England. It is 25 feet in diameter at its base and 12 feet in diameter at the top.

An additional $19,973 was appropriated in 1854 for "procuring illuminating apparatus, and completing the light-house tower and buildings..." The new second-order Fresnel lens went into operation on January 1, 1855.

Poet Celia Thaxter described the lighthouse in her 1873 book, Among the Isles of Shoals:

A slender column against the sky... Sometimes it looms colossal in the mirage of summer; in winter it lies blurred and ghostly at the edge of the chilly sea and pallid sky.

In 1876, 14-year-old Annie Bell Hobbs, daughter of Assistant Keeper Edwin Hobbs, wrote an article about life at Boon Island for a children's magazine called Nursery.

From Ye Romance of Old York by Herbert M. Sylvester, 1906

She wrote:

Out at sea, on a rock eight miles from the nearest point of land and about nine miles east of the town of Kittery, is Boon Island, upon which I have been a prisoner, with the privilege of the yard, the past two years.

I will give you a description of the place and its inhabitants. The island is made up of nothing but rocks, without one foot of ground for trees, shrubs, or grass. Now and then sails dot the wide expanse, reminding me that there is a world besides the one I dwell in, all surrounded by water.

The inhabitants of this island consist of eight persons -- just the number that entered the ark at the time of the flood. There are three men, the three keepers of the light, whose duties are to watch the light all night, to warn the sailors of danger. There are two families of us, and in my father's family are five members... Our colony is so small, and the children so few, that the inhabitants have concluded not to build a schoolhouse. Consequently I have my father and mother for teachers...

In the summer we have quite a number of visitors, who board at the beaches during the season. They come to see the lighthouse and all it contains; and we are very glad to show them all, though it is quite tiresome to go up into the light a number of times during the day, since it is one hundred and twenty-three feet from the rock on which it stands to the light.

Up there among the clouds, my father and the other keepers have to watch, night after night, through storms as well as pleasant weather, through summer and winter, the year round, from sunset to sunrise; so that the poor sailors may be warned off from danger.

Out at sea, on a rock eight miles from the nearest point of land and about nine miles east of the town of Kittery, is Boon Island, upon which I have been a prisoner, with the privilege of the yard, the past two years.

I will give you a description of the place and its inhabitants. The island is made up of nothing but rocks, without one foot of ground for trees, shrubs, or grass. Now and then sails dot the wide expanse, reminding me that there is a world besides the one I dwell in, all surrounded by water.

The inhabitants of this island consist of eight persons -- just the number that entered the ark at the time of the flood. There are three men, the three keepers of the light, whose duties are to watch the light all night, to warn the sailors of danger. There are two families of us, and in my father's family are five members... Our colony is so small, and the children so few, that the inhabitants have concluded not to build a schoolhouse. Consequently I have my father and mother for teachers...

In the summer we have quite a number of visitors, who board at the beaches during the season. They come to see the lighthouse and all it contains; and we are very glad to show them all, though it is quite tiresome to go up into the light a number of times during the day, since it is one hundred and twenty-three feet from the rock on which it stands to the light.

Up there among the clouds, my father and the other keepers have to watch, night after night, through storms as well as pleasant weather, through summer and winter, the year round, from sunset to sunrise; so that the poor sailors may be warned off from danger.

In 1889, it was reported that the keeper's dwelling had problems with leaks and was cold and unsuitable for occupation. The house was largely rebuilt and an upper story was added. In the following year a stone and brick oil house was built.

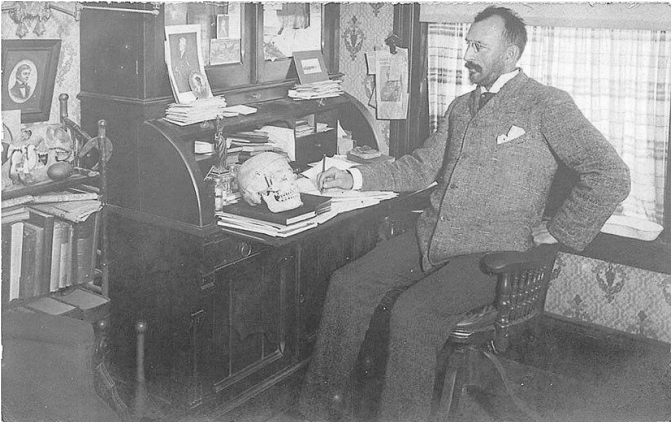

William C. Williams. Courtesy of William O. Thomson

Capt. William C. Williams, a native of Kittery, Maine, went to Boon Island as an assistant in 1885 and served as principal keeper from 1888 to 1911. At the age of 90 he recounted his experiences to Robert Thayer Sterling, author of Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them. Captain Williams had pleasant times at Boon Island, but he later remembered the danger of the job:

The seas would clean the ledge right off sometimes... I was always thinking over just what I would do in order to save my life, should the whole station be swept away.

In an 1888 storm, Williams and the others on the island had to take refuge at the top of the tower for three days. Compared to this storm, said the keeper, the famous "Portland" Gale of 1898 was "just a breeze."

One Thanksgiving, Williams and his assistants were unable to go ashore to buy a turkey. Providence intervened when a dozen black ducks smashed into the tower, providing the keepers with their Thanksgiving dinner.

A Boon Island legend concerns a keeper of the nineteenth century who arrived at the island with his new bride. After a few happy months the keeper fell ill and died during a gale. His wife realized the importance of keeping the light and, despite her grief, managed to climb the tower's 168 stairs and light the lamp for the duration of the storm, which lasted several days.

The seas would clean the ledge right off sometimes... I was always thinking over just what I would do in order to save my life, should the whole station be swept away.

In an 1888 storm, Williams and the others on the island had to take refuge at the top of the tower for three days. Compared to this storm, said the keeper, the famous "Portland" Gale of 1898 was "just a breeze."

One Thanksgiving, Williams and his assistants were unable to go ashore to buy a turkey. Providence intervened when a dozen black ducks smashed into the tower, providing the keepers with their Thanksgiving dinner.

A Boon Island legend concerns a keeper of the nineteenth century who arrived at the island with his new bride. After a few happy months the keeper fell ill and died during a gale. His wife realized the importance of keeping the light and, despite her grief, managed to climb the tower's 168 stairs and light the lamp for the duration of the storm, which lasted several days.

Soon after the storm ended local mariners noticed the lack of a light at Boon Island. They landed to investigate and found the young woman wandering the rocks aimlessly, driven mad by grief and exhaustion. The young woman supposedly died a few weeks later.

Another story concerns keepers who were marooned on the island for weeks by bad weather. Their food had almost run out when they sent a bottle adrift containing an urgent plea for help. A passing schooner picked up the bottle and managed to get a barrel of food to the keepers, which may have saved their lives.

The granite keepers' dwelling had problems with leaks because of “defective linings and a defective roof,” and it was cold and deemed unsuitable for occupation. The house was largely rebuilt and a second story was added in 1889. In the following year, a stone and brick oil house was built. The station’s 1,200-pound fog bell was repositioned onto a belfry atop the oil house, to be rung by hand in response to signals from vessels. An additional wood-frame, one-and-one-half story, six-room keeper’s house was added in 1904, and it became the home of the principal keeper and his family.

In his book Storms and Shipwrecks of New England, Edward Rowe Snow wrote of a powerful storm that hit Boon Island in November 1945. John H. Morris was keeper at the time and was at the station along his wife, Gertrude, their child, Lorne, and the assistant keeper, Ted Guice.

The granite keepers' dwelling had problems with leaks because of “defective linings and a defective roof,” and it was cold and deemed unsuitable for occupation. The house was largely rebuilt and a second story was added in 1889. In the following year, a stone and brick oil house was built. The station’s 1,200-pound fog bell was repositioned onto a belfry atop the oil house, to be rung by hand in response to signals from vessels. An additional wood-frame, one-and-one-half story, six-room keeper’s house was added in 1904, and it became the home of the principal keeper and his family.

In his book Storms and Shipwrecks of New England, Edward Rowe Snow wrote of a powerful storm that hit Boon Island in November 1945. John H. Morris was keeper at the time and was at the station along his wife, Gertrude, their child, Lorne, and the assistant keeper, Ted Guice.

The storm was threatening to destroy the buildings, so Morris took his family to the assistant keepers' house, which was partly sheltered by the tower, and they weathered the storm.

Morris later told Snow:

What really scared us was the sound that the rocks made as they hit against each other. Not a stone on the island was left unturned. The generator failed when a giant sea broke right into the engine room, and we had to operate for the rest of the storm with kerosene lamps. The waves actually climbed halfway up the side of the lighthouse tower itself. I shall never forget that Gale of '45.

Coast Guardsman Kendrick Capon was at Boon Island for a time in the 1950s. Forty years later, Capon told the York Weekly, "The island isn't much bigger than my yard, and after a while, you'd sense where the other person was. You'd become accustomed to hearing the sounds."

One day, after becoming aware that the other keeper was not in the house, Capon looked outside to see the man, a steeplejack's son, shimmying his way down the lightning rod that runs the length of the tower. When he got halfway down, the copper rod began to cut into the man's hands. By the time he reached the bottom his hands were cut to the bone. "He was in bad shape," remembered Capon.

Capon recalled being stuck on Boon Island for 83 days in one stretch, living on bologna, bread, and crackers. Despite the hardships, Capon remembered his lighthouse days fondly. "After about the second or third day, you feel completely relaxed," he said. "I've never felt that relaxed since. I've never been able to capture that."

When Capon was at Boon Island, the keepers would pass the time by telling stories. "We would sit and tell ghost stories to each other until late and then we'd strap on a gun to go out and check the motors," he recalled. "That's where all the cannibalism took place."

Ray Clark was a Coast Guard keeper for about a year, from July 1967 to July 1968. Four men were assigned to he station at the time, and there were generally at least two men at the station. Each man had two weeks on the island, followed by a week off, and watches were divided into 8 or 12 hour shifts. Clark later described the experience:

We'd report in to Portsmouth Harbor Station by 6 a.m. on a Friday, which was supply run day for us and Isles of Shoals, load the 40-footer with groceries delivered by our local market and proceed out if landing conditions were all right. Getting on/off the island was done in our 15-foot "peapod" dinghy. The man coming off rode the rails down and out to the 40-footer and transferred on, while groceries/man going on rowed in standing up, facing forward, so we could judge the swells to hit the rails. The man or men on the island attached the grab hook and pulled on the line we had attached to the engine clutch to hoist the dinghy up into the boathouse.

We had an extremely large day room for relaxation, which had our TV. We had a rotational antenna so we were able to get Portland and Boston stations. At times, with the right conditions, we even got New York stations, but not often.

Daily life was fairly relaxed as long as we got our work done. We all pitched in to help with whatever needed to be done. I was fairly proficient in cooking so I did most of it, but each man could do his own if he chose. The sea was our garbage pit so to speak for all trash/waste. We did do a lot of fishing, which our two dogs loved us for, as they loved the fish heads. Between that and them playing among the seaweed, etc., they stunk up the day room pretty good, so they got washed frequently. We also had a good working agreement with the local lobstermen and were able to haul traps as long as we only took one if there were a sufficient number in them. We ate well!

The most asked question I got was whether the horn bothered us. Actually it didn't, you got so used to it that when we had a problem with a compressor/etc. we noticed it right away by the lack of hearing it. The only times we needed the horn was when we couldn't see Nubble (Cape Neddick Light), otherwise it was just the normal light at night.

Once, there was two of us aboard. He had night watch so I was tanning on the helo pad. All of a sudden I hear a strange voice asking if they could tour the station. Boaters had rowed ashore. Gave me a bit of a start!

Another time, I had a couple weddings I wanted to attend so I stayed aboard five weeks to have two off. Naturally, the TV goes on the fritz. Good thing we have a decent library. It's a night watch, about 3:00 a.m., and I'm reading about the island history and cannibalism when I hear this tapping at the big picture window. Now that's scary! I finally figured out it was small birds attracted by the light and flying into the window.

Two best views: Mt.Washington is very impressive on a clear day. Portland Head Light at night from the top of the tower.

What really scared us was the sound that the rocks made as they hit against each other. Not a stone on the island was left unturned. The generator failed when a giant sea broke right into the engine room, and we had to operate for the rest of the storm with kerosene lamps. The waves actually climbed halfway up the side of the lighthouse tower itself. I shall never forget that Gale of '45.

Coast Guardsman Kendrick Capon was at Boon Island for a time in the 1950s. Forty years later, Capon told the York Weekly, "The island isn't much bigger than my yard, and after a while, you'd sense where the other person was. You'd become accustomed to hearing the sounds."

One day, after becoming aware that the other keeper was not in the house, Capon looked outside to see the man, a steeplejack's son, shimmying his way down the lightning rod that runs the length of the tower. When he got halfway down, the copper rod began to cut into the man's hands. By the time he reached the bottom his hands were cut to the bone. "He was in bad shape," remembered Capon.

Capon recalled being stuck on Boon Island for 83 days in one stretch, living on bologna, bread, and crackers. Despite the hardships, Capon remembered his lighthouse days fondly. "After about the second or third day, you feel completely relaxed," he said. "I've never felt that relaxed since. I've never been able to capture that."

When Capon was at Boon Island, the keepers would pass the time by telling stories. "We would sit and tell ghost stories to each other until late and then we'd strap on a gun to go out and check the motors," he recalled. "That's where all the cannibalism took place."

Ray Clark was a Coast Guard keeper for about a year, from July 1967 to July 1968. Four men were assigned to he station at the time, and there were generally at least two men at the station. Each man had two weeks on the island, followed by a week off, and watches were divided into 8 or 12 hour shifts. Clark later described the experience:

We'd report in to Portsmouth Harbor Station by 6 a.m. on a Friday, which was supply run day for us and Isles of Shoals, load the 40-footer with groceries delivered by our local market and proceed out if landing conditions were all right. Getting on/off the island was done in our 15-foot "peapod" dinghy. The man coming off rode the rails down and out to the 40-footer and transferred on, while groceries/man going on rowed in standing up, facing forward, so we could judge the swells to hit the rails. The man or men on the island attached the grab hook and pulled on the line we had attached to the engine clutch to hoist the dinghy up into the boathouse.

We had an extremely large day room for relaxation, which had our TV. We had a rotational antenna so we were able to get Portland and Boston stations. At times, with the right conditions, we even got New York stations, but not often.

Daily life was fairly relaxed as long as we got our work done. We all pitched in to help with whatever needed to be done. I was fairly proficient in cooking so I did most of it, but each man could do his own if he chose. The sea was our garbage pit so to speak for all trash/waste. We did do a lot of fishing, which our two dogs loved us for, as they loved the fish heads. Between that and them playing among the seaweed, etc., they stunk up the day room pretty good, so they got washed frequently. We also had a good working agreement with the local lobstermen and were able to haul traps as long as we only took one if there were a sufficient number in them. We ate well!

The most asked question I got was whether the horn bothered us. Actually it didn't, you got so used to it that when we had a problem with a compressor/etc. we noticed it right away by the lack of hearing it. The only times we needed the horn was when we couldn't see Nubble (Cape Neddick Light), otherwise it was just the normal light at night.

Once, there was two of us aboard. He had night watch so I was tanning on the helo pad. All of a sudden I hear a strange voice asking if they could tour the station. Boaters had rowed ashore. Gave me a bit of a start!

Another time, I had a couple weddings I wanted to attend so I stayed aboard five weeks to have two off. Naturally, the TV goes on the fritz. Good thing we have a decent library. It's a night watch, about 3:00 a.m., and I'm reading about the island history and cannibalism when I hear this tapping at the big picture window. Now that's scary! I finally figured out it was small birds attracted by the light and flying into the window.

Two best views: Mt.Washington is very impressive on a clear day. Portland Head Light at night from the top of the tower.

According to Robert Ellis Cahill's book, Lighthouse Mysteries of the North Atlantic, a ghost has been seen by many people on Boon Island.

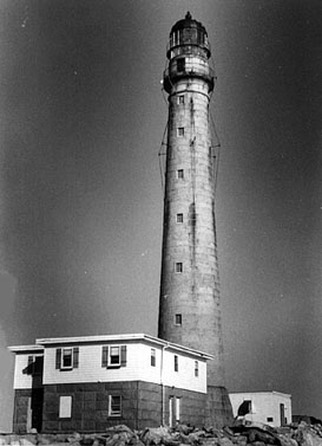

Circa 1990. © Jeremy D'Entremont.

The ghost is described as "a sad faced young woman shrouded in white." This phantom has been seen by keepers and fishermen, wrote Cahill. Some say the woman in white is the ghost of the mistress of the captain of the Nottingham Galley, while others claim she is the young bride whose husband died on the island one winter.

Bob Roberts, a Coast Guard keeper in the early 1970s, says the other keepers asked him if he believed in ghosts when he first went to Boon Island. Roberts laughed at the time, but strange events on the island soon had him thinking differently. One time, he and fellow crewman Bob Edwards were off the island fishing, and they drifted too far from the island to make it back in time to turn the light on before dark. There wasn't a person on the island, but somehow the light was glowing brightly by the time the keepers returned.

Bob Roberts, a Coast Guard keeper in the early 1970s, says the other keepers asked him if he believed in ghosts when he first went to Boon Island. Roberts laughed at the time, but strange events on the island soon had him thinking differently. One time, he and fellow crewman Bob Edwards were off the island fishing, and they drifted too far from the island to make it back in time to turn the light on before dark. There wasn't a person on the island, but somehow the light was glowing brightly by the time the keepers returned.

On other occasions Roberts and others heard doors mysteriously opening and closing. When he would go to turn on the fog signal, Roberts said he felt as if "someone was watching."

The lens at the Kittery Historical & Naval Museum

Another former Coast Guard keeper, Dave Wells, says that one time the station's Labrador retriever chased "something from one end of the island to the other and back again." The Coast Guardsmen couldn't see what the dog was chasing. "We figured the island must be haunted, but nothing ever bothered us," says Wells.

Coast Guard keepers reported weather conditions every three hours to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. They also monitored the Cape Neddick "Nubble" Light. When the light from Cape Neddick couldn't be seen, it was time to turn on the fog signal.

A severe storm in February 1972 a destroyed the boathouse and swept boulders, along with five feet of water, into the keeper's house. The storm broke every window in the house and also destroyed a wall of the boathouse. The Coast Guard crew had to use a jackhammer to remove giant stones from around the dwelling.

Even this wasn't as bad as the great blizzard of 1978. The early February storm, one of the worst in New England history, flooded the 1899 keeper's house to the ceiling of the first floor and scattered boulders around like they were pebbles. A large fuel talk floated right through the house from east to west.

The Coast Guard keepers (Kirby Eldridge and Leo Berry) were forced to take refuge in the tower. The following day the keepers were removed by helicopter. It was estimated that $100,000 worth of damage was done at Boon Island by the blizzard of '78.

Shortly after the blizzard of '78, the light was automated. In 1993, the second-order Fresnel lens was removed and replaced by a modern optic.

The Fresnel lens remained in storage at the Coast Guard's Aids to Navigation Team's facility in South Portland until April 2000, when it was put on display at the Kittery Historical and Naval Museum. The town of Kittery, just south of York, has strong historical ties to the lighthouse; many of the keepers were natives of the town.

The property was made available in 2012 to a new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act, but there were no applicants. As a result, it was put up for sale via online auction in May 2014. The auction ended in August 2014; the high bid of $78,000 was placed by Portland, Maine, real estate developer Arthur Girard. He sold it a few months later. The owner is now Bobby Sager, a Boston philanthropist.

Boon Island Light can be seen distantly from the shores of York, but is best seen from a boat or from the air.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

David Oliver (c. 1811); Thomas Hanna (c. 1811-1816); Eliphalet Grover (1816-1839); Joseph P. Jenkins (c. 1839-1840); Mark Dennet (1840-1841); John Thompson (1841-1843 and 1849-1853); Morgan Trafton (1842, assistant keeper, died in boating accident); John Kennard (1843-1846); Nathaniel Baker (1846-1849); Benjamin O. Fletcher (assistant c. 1849); Caleb S. Gould (1853-1854); George Bowden (1854-1855); Samuel S. Tobey (assistant, 1856); Christopher Littlefield (1854); Sam Philbrick (1854); Charles H. Tobey (assistant 1850, keeper 1856); Charles E. Thompson (1858); John S. Baker (assistant, 1858); Nathaniel Baker (1859); Hiram Tobey (1859); Josiah Tobey Jr. (assistant, 1855; principal keeper ?-1859); Joseph H. Hart (c. 1859-1861); William L. Baker (assistant, 1859); Cabin (?) Gray (1861); George B. Wallace (June 1861-1866); Benjamin Bridges (1861); George E. Bridges (assistant, 1864-1865); Richard C. Yeaton (1864); Charles Ramsdell (assistant 1865); Joshua Kenney Card (1867-1874); John W. Card (assistant, c. 1873); George H. Yeaton (assistant 1867); Samuel Meloon (assistant, 1868); Luther Amazeen (assistant 1868-1870); Nathan White Jr. (assistant c. 1870-1873); Alfred J. Leavitt (1874-1886); Leander White (first assistant, 1874-1878); Edwin J. Hobbs (assistant, 1874-1876); David R. Grogan (assistant, 1876, keeper 1879); George O. Leavitt (second assistant, 1878-1880, first assistant 1880-?); Walter S. Amee (second assistant, 1878); Paschal Fernald (secnd assistant 1880-?); John Kennard (1884); William C. Williams (second assistant 1885-1886, first assistant 1886-1888, principal keeper 1888-1911); James Burke (second assistant, 1886-1887, first assistant 1887-1890); Orrin M. Lamprey (1886-1888); Meshach M. Seaward (second assistant, 1886-1900); Leonidas H. Sawyer (second assistant, 1889, principal keeper 1889); Charles W. Torrey (first assistant, ?-1893); William M. Brooks (assistant, 1893-1897); Charles S. Williams (second assistant, c. 1895-1897, first assistant 1897-1905); William T. Stevens (first assistant, c. 1905); Charles W. Allen (second assistant, 1907-1911, first assistant 1911-?); Mitchell Blackwood (second assistant c. 1905, then first assistant, then principal keeper 1911-1916); Roger Paul Philbrick (first assistant 1913-1918); Albert Staples (second assistant, c. 1913-?, principal keeper 1920-1923); Harry Smith (1916-1920); Harold Hutchins (1924-1933); Fred C. Batty (assistant, c. early 1930s); Eugene L. Coleman (second assistant, then first assistant, 1923-1930); Clinton Dalzell (assistant c. 1934); George Woodward (assistant?, c. 1920s); Charles Edward Tracy (1933-1935); Hoyt P. Smith (1935-1942); F. A. Rumery (assistant, c. 1933-?); E. Stockbridge, assistant (c. 1935)

COAST GUARD

Charles U. Gardner ( relief keeper, c, 1942-1943); Warren Alley (1941-1943); Calvin Dolby (c. 1944-1945); Jack McCoe (c. 1944-1945); William Parmenar [Parmenter?] c. 1944-1945); John H. Morris (c. 1945); Ted Guice (c. 1945); ? Watts (c. 1953); Kendrick Capon (1951-1953); Jerry Russell (c. 1954); Harold L. Roberts (1956); Leonard John "Moon" Mullen (1958-1961); Robert Brann (c. 1958); Ron Schultz (1959); Charles Eaton (1962-1965); David Wells (1966); Arthur D. Blackburn (1965-1967); August "Gus" Pfister (1967-1968); Raymond Clark (July 1967 - July 1968); Robert Edwards (officer in charge, c. 1970-1973); Bob Roberts (1971-1972); Garth Clough ( c. 1970-1972); Thomas J. Lee (July 1970 to October 1971); Richard Heon (early 1970s); Stephen Garsznksi (c. 1972); Fred Kendall (1973-1975); Jack W. Straley (Feb. 1977-Feb. 1978); William Ripka (c. 1977-1978); Kirby Eldridge (?-1978); Leo Berry (?-1978)

Coast Guard keepers reported weather conditions every three hours to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. They also monitored the Cape Neddick "Nubble" Light. When the light from Cape Neddick couldn't be seen, it was time to turn on the fog signal.

A severe storm in February 1972 a destroyed the boathouse and swept boulders, along with five feet of water, into the keeper's house. The storm broke every window in the house and also destroyed a wall of the boathouse. The Coast Guard crew had to use a jackhammer to remove giant stones from around the dwelling.

Even this wasn't as bad as the great blizzard of 1978. The early February storm, one of the worst in New England history, flooded the 1899 keeper's house to the ceiling of the first floor and scattered boulders around like they were pebbles. A large fuel talk floated right through the house from east to west.

The Coast Guard keepers (Kirby Eldridge and Leo Berry) were forced to take refuge in the tower. The following day the keepers were removed by helicopter. It was estimated that $100,000 worth of damage was done at Boon Island by the blizzard of '78.

Shortly after the blizzard of '78, the light was automated. In 1993, the second-order Fresnel lens was removed and replaced by a modern optic.

The Fresnel lens remained in storage at the Coast Guard's Aids to Navigation Team's facility in South Portland until April 2000, when it was put on display at the Kittery Historical and Naval Museum. The town of Kittery, just south of York, has strong historical ties to the lighthouse; many of the keepers were natives of the town.

The property was made available in 2012 to a new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act, but there were no applicants. As a result, it was put up for sale via online auction in May 2014. The auction ended in August 2014; the high bid of $78,000 was placed by Portland, Maine, real estate developer Arthur Girard. He sold it a few months later. The owner is now Bobby Sager, a Boston philanthropist.

Boon Island Light can be seen distantly from the shores of York, but is best seen from a boat or from the air.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

David Oliver (c. 1811); Thomas Hanna (c. 1811-1816); Eliphalet Grover (1816-1839); Joseph P. Jenkins (c. 1839-1840); Mark Dennet (1840-1841); John Thompson (1841-1843 and 1849-1853); Morgan Trafton (1842, assistant keeper, died in boating accident); John Kennard (1843-1846); Nathaniel Baker (1846-1849); Benjamin O. Fletcher (assistant c. 1849); Caleb S. Gould (1853-1854); George Bowden (1854-1855); Samuel S. Tobey (assistant, 1856); Christopher Littlefield (1854); Sam Philbrick (1854); Charles H. Tobey (assistant 1850, keeper 1856); Charles E. Thompson (1858); John S. Baker (assistant, 1858); Nathaniel Baker (1859); Hiram Tobey (1859); Josiah Tobey Jr. (assistant, 1855; principal keeper ?-1859); Joseph H. Hart (c. 1859-1861); William L. Baker (assistant, 1859); Cabin (?) Gray (1861); George B. Wallace (June 1861-1866); Benjamin Bridges (1861); George E. Bridges (assistant, 1864-1865); Richard C. Yeaton (1864); Charles Ramsdell (assistant 1865); Joshua Kenney Card (1867-1874); John W. Card (assistant, c. 1873); George H. Yeaton (assistant 1867); Samuel Meloon (assistant, 1868); Luther Amazeen (assistant 1868-1870); Nathan White Jr. (assistant c. 1870-1873); Alfred J. Leavitt (1874-1886); Leander White (first assistant, 1874-1878); Edwin J. Hobbs (assistant, 1874-1876); David R. Grogan (assistant, 1876, keeper 1879); George O. Leavitt (second assistant, 1878-1880, first assistant 1880-?); Walter S. Amee (second assistant, 1878); Paschal Fernald (secnd assistant 1880-?); John Kennard (1884); William C. Williams (second assistant 1885-1886, first assistant 1886-1888, principal keeper 1888-1911); James Burke (second assistant, 1886-1887, first assistant 1887-1890); Orrin M. Lamprey (1886-1888); Meshach M. Seaward (second assistant, 1886-1900); Leonidas H. Sawyer (second assistant, 1889, principal keeper 1889); Charles W. Torrey (first assistant, ?-1893); William M. Brooks (assistant, 1893-1897); Charles S. Williams (second assistant, c. 1895-1897, first assistant 1897-1905); William T. Stevens (first assistant, c. 1905); Charles W. Allen (second assistant, 1907-1911, first assistant 1911-?); Mitchell Blackwood (second assistant c. 1905, then first assistant, then principal keeper 1911-1916); Roger Paul Philbrick (first assistant 1913-1918); Albert Staples (second assistant, c. 1913-?, principal keeper 1920-1923); Harry Smith (1916-1920); Harold Hutchins (1924-1933); Fred C. Batty (assistant, c. early 1930s); Eugene L. Coleman (second assistant, then first assistant, 1923-1930); Clinton Dalzell (assistant c. 1934); George Woodward (assistant?, c. 1920s); Charles Edward Tracy (1933-1935); Hoyt P. Smith (1935-1942); F. A. Rumery (assistant, c. 1933-?); E. Stockbridge, assistant (c. 1935)

COAST GUARD

Charles U. Gardner ( relief keeper, c, 1942-1943); Warren Alley (1941-1943); Calvin Dolby (c. 1944-1945); Jack McCoe (c. 1944-1945); William Parmenar [Parmenter?] c. 1944-1945); John H. Morris (c. 1945); Ted Guice (c. 1945); ? Watts (c. 1953); Kendrick Capon (1951-1953); Jerry Russell (c. 1954); Harold L. Roberts (1956); Leonard John "Moon" Mullen (1958-1961); Robert Brann (c. 1958); Ron Schultz (1959); Charles Eaton (1962-1965); David Wells (1966); Arthur D. Blackburn (1965-1967); August "Gus" Pfister (1967-1968); Raymond Clark (July 1967 - July 1968); Robert Edwards (officer in charge, c. 1970-1973); Bob Roberts (1971-1972); Garth Clough ( c. 1970-1972); Thomas J. Lee (July 1970 to October 1971); Richard Heon (early 1970s); Stephen Garsznksi (c. 1972); Fred Kendall (1973-1975); Jack W. Straley (Feb. 1977-Feb. 1978); William Ripka (c. 1977-1978); Kirby Eldridge (?-1978); Leo Berry (?-1978)