History of Curtis Island Light, Camden, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Camden Harbor is finely locked in between two jutting points of land, one high, the other low, with a pretty little wooded island deftly dropped in at the entrance. Negro Island is its name. The harbor light stands on this island. Back of this, the mountains rise so near at hand that the village spires are thrown up against them in strong relief... Sails bathed in sunshine look like cloths of gold; masts and ropes, like cobwebs borne along by the breeze. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

Camden and its harbor from the top of Mount Battie in the Camden Hills

Camden's well-protected harbor helped the town develop major lime-kiln and shipbuilding industries in the nineteenth century. Today, thousands of tourists come to the town each year, attracted by the combination of the handsome harbor, the beauty of Penobscot Bay and the nearby Camden Hills, and a cluster of shops and restaurants. The town was the setting for the movie Peyton Place, and for the 1995 film Thinner, based on a Stephen King novel.

Seven-acre Curtis Island, a short distance offshore at the entrance to the harbor, was long known as Negro Island. According to a 1922 article, it got its name because an African-American cook, aboard the vessel that brought the early settler James Richards to Camden in 1769, expressed his admiration for the island as they sailed past. To aid local navigation, Congress appropriated $4,500 for a lighthouse on the island on June 30, 1834. John Dorr of Boston sold the property to the federal government for $400.

Seven-acre Curtis Island, a short distance offshore at the entrance to the harbor, was long known as Negro Island. According to a 1922 article, it got its name because an African-American cook, aboard the vessel that brought the early settler James Richards to Camden in 1769, expressed his admiration for the island as they sailed past. To aid local navigation, Congress appropriated $4,500 for a lighthouse on the island on June 30, 1834. John Dorr of Boston sold the property to the federal government for $400.

For a sum of $2,569, the contractor George Galt (or Gault) built a rubblestone lighthouse, 20 feet tall to the lantern deck, along with a stone dwelling with three rooms on the first floor and three small rooms in the attic.

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Joseph Berry, a contractor from Georgetown, Maine, installed eight oil lamps and accompanying 14-inch reflectors for $650.

Also involved in construction was the mason Oliver A. Andrews of Rockport, who later served in the state legislature and as deputy sheriff of Lincoln County.

The fixed white light went into service in 1836, and Henry K. M Bower (or Bowers) was the first keeper. Bower cultivated a garden and was given permission to cut down trees on the island for wood. As was common at lighthouses at that time, the keepers kept animals, including cows, ducks, and chickens.

Obadiah Brown served two stints as keeper, 1845–49 and 1855–57. When Brown died in July 1857, a newspaper reported, “Mr. Brown in building [a] wall upon the island injured his stomach which resulted in his death.” Brown was “universally respected,” according to the newspaper.

Also involved in construction was the mason Oliver A. Andrews of Rockport, who later served in the state legislature and as deputy sheriff of Lincoln County.

The fixed white light went into service in 1836, and Henry K. M Bower (or Bowers) was the first keeper. Bower cultivated a garden and was given permission to cut down trees on the island for wood. As was common at lighthouses at that time, the keepers kept animals, including cows, ducks, and chickens.

Obadiah Brown served two stints as keeper, 1845–49 and 1855–57. When Brown died in July 1857, a newspaper reported, “Mr. Brown in building [a] wall upon the island injured his stomach which resulted in his death.” Brown was “universally respected,” according to the newspaper.

According to an 1850 inspection report, the tower was leaky and in need of repointing, and the whole establishment was in need of “immediate attention.”

The Lighthouse Board achieved an inexpensive temporary fix in 1855, when the stone tower was encased in an octagonal wooden outer sheath and shingled in an effort to stop the problem with leaks. In the following year, a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the eight lamps and reflectors. The dwelling was largely overhauled in 1867–68, and a new woodshed was added to the station.

For many years, the island served as a signal station for the large steamships that passed by. When the keeper saw one of the passenger steamers approaching, he hoisted a large ball to the top of a tall pole. The word would go out that “the ball is up,” and Camden hack drivers and others would prepare for the arrival of the vessel at the steamboat wharf.

For many years, the island served as a signal station for the large steamships that passed by. When the keeper saw one of the passenger steamers approaching, he hoisted a large ball to the top of a tall pole. The word would go out that “the ball is up,” and Camden hack drivers and others would prepare for the arrival of the vessel at the steamboat wharf.

In 1889, while Henry Wiley was keeper, a new wood-frame dwelling was built on the original foundation.

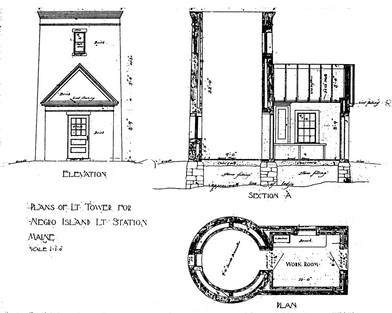

Plans for the 1896 lighthouse tower (U.S. Coast Guard)

A local newspaper reported:

The light keeper’s new dwelling on Negro Island has just been completed. It is in a modern and pleasing style of architecture and very convenient. It contains six large, airy, well lighted rooms, beside numerous closets, halls &c. Every floor in the house is of hard pine and the whole house is built in the most thorough manner and of the best materials. . . . Capt. Wiley, the courteous and efficient keeper and Mrs. Wiley seem very much pleased with their new and comfortable home.

The present 25-foot-tall brick tower replaced the original lighthouse in 1896. A "Notice to Mariners" announced the following in the spring of 1896:

Notice is hereby given that on or about May 11, 1896, the fourth order fixed white light at this station . . . will be moved to and exhibited from a temporary, unpainted, wooden skeleton tower, 40 feet east northeast, one-half east from the present tower.

Then, in early August, the following announcement was made:

The new lighthouse on Negro Island, Camden, is finished, and the light was placed in position Friday and the temporary structure removed. Capt. Wiley, the lighthouse keeper, is seriously ill.

Henry Wiley, who had been keeper since 1882, died a short time later. A new 1200-pound fog bell with automatic striking machinery was installed on the island in October 1896.

With its easy proximity to town and attractive setting, Negro Island was a sought-after family light station. Several keepers served lengthy stints on the island, including Henry Wiley (1882–96), Howard M. Gilley (1896–1909), Aldiverd Alteverd A. Norton (1909–19), and Elmer Reed (1919–38). Because the island was so easy to access, it also was a favorite picnic spot for generations of area residents and visitors.

The light keeper’s new dwelling on Negro Island has just been completed. It is in a modern and pleasing style of architecture and very convenient. It contains six large, airy, well lighted rooms, beside numerous closets, halls &c. Every floor in the house is of hard pine and the whole house is built in the most thorough manner and of the best materials. . . . Capt. Wiley, the courteous and efficient keeper and Mrs. Wiley seem very much pleased with their new and comfortable home.

The present 25-foot-tall brick tower replaced the original lighthouse in 1896. A "Notice to Mariners" announced the following in the spring of 1896:

Notice is hereby given that on or about May 11, 1896, the fourth order fixed white light at this station . . . will be moved to and exhibited from a temporary, unpainted, wooden skeleton tower, 40 feet east northeast, one-half east from the present tower.

Then, in early August, the following announcement was made:

The new lighthouse on Negro Island, Camden, is finished, and the light was placed in position Friday and the temporary structure removed. Capt. Wiley, the lighthouse keeper, is seriously ill.

Henry Wiley, who had been keeper since 1882, died a short time later. A new 1200-pound fog bell with automatic striking machinery was installed on the island in October 1896.

With its easy proximity to town and attractive setting, Negro Island was a sought-after family light station. Several keepers served lengthy stints on the island, including Henry Wiley (1882–96), Howard M. Gilley (1896–1909), Aldiverd Alteverd A. Norton (1909–19), and Elmer Reed (1919–38). Because the island was so easy to access, it also was a favorite picnic spot for generations of area residents and visitors.

The name of the island was changed to Curtis Island in 1934 in memory of Cyrus H.K. Curtis, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post and other publications. He had died in the previous year.

Curtis was a longtime summer resident and benefactor of Camden. He gave the town the land and building that became the Camden Yacht Club.

Six Coast Guardsmen were stationed on the island during World War II. It was reported that the men were treated like sons by Myrick Morrison, keeper of the light at the time.

Left: Keeper Myrick Morrison, courtesy of North Haven Historical Society.

In 1970, word spread that the Coast Guard was planning to auction the light station, except for the tower. Three Camden residents traveled to Philadelphia for a meeting and managed to convince the Coast Guard that the station should go to the Town of Camden rather than a private party.

Six Coast Guardsmen were stationed on the island during World War II. It was reported that the men were treated like sons by Myrick Morrison, keeper of the light at the time.

Left: Keeper Myrick Morrison, courtesy of North Haven Historical Society.

In 1970, word spread that the Coast Guard was planning to auction the light station, except for the tower. Three Camden residents traveled to Philadelphia for a meeting and managed to convince the Coast Guard that the station should go to the Town of Camden rather than a private party.

The light was automated in 1972. The Coast Guard keepers were removed and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern optic.

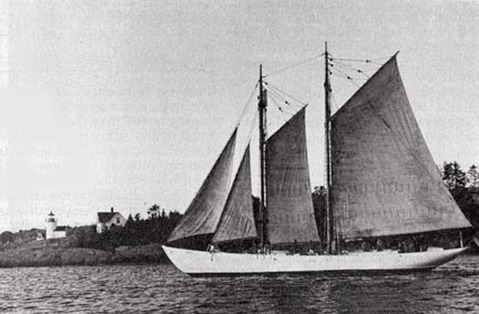

The Arctic exploration schooner Bowdoin passes Curtis Island, circa 1920s

The Town of Camden officially acquired the property, except for the lighthouse, during the following year. The light is now solar-powered and is an active aid to navigation maintained by the Coast Guard.

In 1980, Garrett Elliot "Connie" Conover, Jr., and his wife, Deedee Conover, began a long stint as the caretakers of the island and light station. The island was the scene of a highly unusual event in September 1993. Deedee Conover saw what she thought was a sick or injured dolphin come ashore. The animal was still alive, and Conover said she felt as if it was trying to talk to her.

The creature soon died, and an autopsy performed by Allied Whale found that it was a 13-foot immature female beaked whale. There have been only sixteen beaked whales ever found in North America, and six in Europe. There has never been a confirmed sighting at sea of a beaked whale.

In 1980, Garrett Elliot "Connie" Conover, Jr., and his wife, Deedee Conover, began a long stint as the caretakers of the island and light station. The island was the scene of a highly unusual event in September 1993. Deedee Conover saw what she thought was a sick or injured dolphin come ashore. The animal was still alive, and Conover said she felt as if it was trying to talk to her.

The creature soon died, and an autopsy performed by Allied Whale found that it was a 13-foot immature female beaked whale. There have been only sixteen beaked whales ever found in North America, and six in Europe. There has never been a confirmed sighting at sea of a beaked whale.

In November 1997, the people of Camden voted to allow the town to assume ownership of Curtis Island Light. Under the Maine Lights Program, created by congressional legislation and coordinated by the Island Institute of Rockland, the lighthouse officially became the property of the Town of Camden in 1998.

A view of Curtis Island from the top of Mount Battie

Caretaker Connie Conover died at the age of 81 in October 2010. Just a few months earlier, he had worked closely with the Coast Guard in the planning of the repainting of the keeper's house. The project was completed in September 2010.

In 2023, the Curtis Island Lighthouse Foundation was established with a mission to historically restore the Curtis Island Light Station and to develop a perpetual maintenance trust fund, all in partnership with the Town of Camden.

This is one of the prettiest light stations in Maine and it looks like its occulting green light will be welcoming boaters to Camden, the "Jewel of the Penobscot," for many years to come. The lighthouse is difficult to see from land, but it can be seen from all the schooners and excursion boats leaving Camden Harbor.

It can be seen from the "Curtis Island Overlook," on Bayview Street, just southeast of the intersection with Beacon Street. Look for the sign and the path leading to the water's edge.

You can also get a breathtaking, panoramic view of Camden Harbor by driving or hiking to the top of Mount Battie in Camden Hills State Park.

In 2023, the Curtis Island Lighthouse Foundation was established with a mission to historically restore the Curtis Island Light Station and to develop a perpetual maintenance trust fund, all in partnership with the Town of Camden.

This is one of the prettiest light stations in Maine and it looks like its occulting green light will be welcoming boaters to Camden, the "Jewel of the Penobscot," for many years to come. The lighthouse is difficult to see from land, but it can be seen from all the schooners and excursion boats leaving Camden Harbor.

It can be seen from the "Curtis Island Overlook," on Bayview Street, just southeast of the intersection with Beacon Street. Look for the sign and the path leading to the water's edge.

You can also get a breathtaking, panoramic view of Camden Harbor by driving or hiking to the top of Mount Battie in Camden Hills State Park.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Henry. K. M. Bower (1836-1841); Ephraim S. Fly (1841-1845); Obadiah Brown (1845-1849 and 1855-1857); William Prince (or Price) (1849-1853); Ebenezer M. Carelton (1853-1855); Andrew M. Annis (1857-1861); Isaiah Barbour (1861-1872 and 1873); Josuha Bramhall (1872-1873 and 1873-1879); Fred D. Aldus (1879-1882); Henry Wiley (1882-1896); Howard M. Gilley (1896-1909); Aldiverd A. Norton (1909-1919); Elmer Reed (1919-1938); Myrick Morrison (1938-1950); Martin Jordan (Coast Guard lookout during WWII, 1942-43); Gordon Bruce (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Joe Ash (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Ted Keller (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Betts Kiesel (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); BM2 Carroll A. Hallowell (1950); Benjamin C. Stockbridge (1950-1951); Albert F. Osgood (1951-1959); Melvin Kirchoff (Coast Guard, ?-?); BM1 Jean B. C. DuBois (DuBios?) (Coast Guard, 1959-1960); EN1 Richard Kwapiszewski (Coast Guard, 1960); EN2 Francis X. McCarthy (Coast Guard, 1960-1962); BM1 James H. Perry (Coast Guard 1962-1964); EN2 John R. French (Coast Guard, 1964-1967?); Allen Jon "Jack" Hamel (Coast Guard, 1967-1968); Thomas W. Christie (Coast Guard, 1968-1970); EM 2 Clifton W. McKenney, Jr. (Coast Guard, 1970-1971); Duke D. Glishke (Coast Guard, early 1970s); FA Roy Fruschertz (Coast Guard automation crew, c.1971-1972); EM1 John Gustin (Coast Guard automation crew, c.1971-1972)

Henry. K. M. Bower (1836-1841); Ephraim S. Fly (1841-1845); Obadiah Brown (1845-1849 and 1855-1857); William Prince (or Price) (1849-1853); Ebenezer M. Carelton (1853-1855); Andrew M. Annis (1857-1861); Isaiah Barbour (1861-1872 and 1873); Josuha Bramhall (1872-1873 and 1873-1879); Fred D. Aldus (1879-1882); Henry Wiley (1882-1896); Howard M. Gilley (1896-1909); Aldiverd A. Norton (1909-1919); Elmer Reed (1919-1938); Myrick Morrison (1938-1950); Martin Jordan (Coast Guard lookout during WWII, 1942-43); Gordon Bruce (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Joe Ash (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Ted Keller (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); Betts Kiesel (Coast Guard lookout during WWII); BM2 Carroll A. Hallowell (1950); Benjamin C. Stockbridge (1950-1951); Albert F. Osgood (1951-1959); Melvin Kirchoff (Coast Guard, ?-?); BM1 Jean B. C. DuBois (DuBios?) (Coast Guard, 1959-1960); EN1 Richard Kwapiszewski (Coast Guard, 1960); EN2 Francis X. McCarthy (Coast Guard, 1960-1962); BM1 James H. Perry (Coast Guard 1962-1964); EN2 John R. French (Coast Guard, 1964-1967?); Allen Jon "Jack" Hamel (Coast Guard, 1967-1968); Thomas W. Christie (Coast Guard, 1968-1970); EM 2 Clifton W. McKenney, Jr. (Coast Guard, 1970-1971); Duke D. Glishke (Coast Guard, early 1970s); FA Roy Fruschertz (Coast Guard automation crew, c.1971-1972); EM1 John Gustin (Coast Guard automation crew, c.1971-1972)