History of Cuttyhunk Light, Massachusetts

More information: Front page / Bibliography / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Cuttyhunk Island is at the southwestern end of the Elizabeth Islands, a chain that extends westward for about 16 miles from the village of Woods Hole in Falmouth on Cape Cod.

U.S. Geological Survey

The 16 islands, which mark the boundary between Vineyard Sound and Buzzards Bay, constitute the town of Gosnold -- the least populated municipality in Massachusetts. The island's name comes from the Algonquin Indian word "Poocutohhunkunnoh," which is generally translated as "point of departure" or "land's end." A number of variations appear in early sources, including "Cutterhunk" and "Cuttahunk."

The island, which is about two miles long and a mile wide, was the scene of one of the earliest English colonies in America. Explorer Bartholomew Gosnold chose Cuttyhunk as a perfect place for a settlement in 1602, largely because of its freshwater pond. The Englishmen used the island as a base to explore the area, including Martha's Vineyard. Gosnold recorded a banquet with the local Indians, who enjoyed the food the visitors provided except for the mustard, which caused them to make a "sowre face."

The island, which is about two miles long and a mile wide, was the scene of one of the earliest English colonies in America. Explorer Bartholomew Gosnold chose Cuttyhunk as a perfect place for a settlement in 1602, largely because of its freshwater pond. The Englishmen used the island as a base to explore the area, including Martha's Vineyard. Gosnold recorded a banquet with the local Indians, who enjoyed the food the visitors provided except for the mustard, which caused them to make a "sowre face."

The first English settlement on the island lasted only three weeks as the Indians became hostile, possibly because the English party had stolen one of their canoes.

Cuttyhunk Light c. 1880s (U.S. Coast Guard)

Coastal shipping traffic in the area was heavy by the early 1800s. In 1830, a total of 12,603 vessels were observed passing Cuttyhunk. The island's southwestern tip was an obvious location for a lighthouse to help guide traffic into Buzzards Bay and eastward into Vineyard Sound. The island's first lighthouse was built in 1823 for $3,000. The 25-foot stone tower exhibited its light from 48 feet above sea level.

When Lt. Edward Carpender inspected the station in 1838, there were 10 lamps with 13-inch reflectors in use. Carpender mentioned that the stone tower had twice been encased in brick. I. W. P. Lewis's examination, reported to Congress in 1843, forcefully confirmed that the lighthouse was not well built. Lewis described the tower as leaky from roof to base, and he said the "whole establishment [is] conducted in the worst manner."

A Fresnel lens replaced Cuttyhunk Light's old lamps and reflectors in 1857. In 1860, the dilapidated old tower was torn down. A second story was added to the keeper's dwelling, and a lantern was erected on the roof. The fixed white light exhibited at that time could be seen for 12 nautical miles in clear weather.

S. Austin Smith, keeper 1864-81, wrote in the station's log soon after taking the position:

Heavy weather. Employed washing, cooking, cleaning the light. This is lonesome. We are all sick.

Alfred G. Eisener, a Maine native, became keeper in 1890. According to a newspaper account, the old dwelling when Eisener moved in was "very damp, and somewhat dilapidated." Funds were soon appropriated for the rebuilding of the dwelling, and for a new 45-foot stone lighthouse.

The design chosen for the new one-and-one-half-story, wood-frame keeper's house was the same as the design of a keeper's house built about the same time at Prospect Harbor, Maine. The first story contained a living room, dining room, kitchen, and pantry, and three bedrooms were located upstairs. A fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the new tower, presumably relocated from the old structure. The new light went into service in 1891.

When Lt. Edward Carpender inspected the station in 1838, there were 10 lamps with 13-inch reflectors in use. Carpender mentioned that the stone tower had twice been encased in brick. I. W. P. Lewis's examination, reported to Congress in 1843, forcefully confirmed that the lighthouse was not well built. Lewis described the tower as leaky from roof to base, and he said the "whole establishment [is] conducted in the worst manner."

A Fresnel lens replaced Cuttyhunk Light's old lamps and reflectors in 1857. In 1860, the dilapidated old tower was torn down. A second story was added to the keeper's dwelling, and a lantern was erected on the roof. The fixed white light exhibited at that time could be seen for 12 nautical miles in clear weather.

S. Austin Smith, keeper 1864-81, wrote in the station's log soon after taking the position:

Heavy weather. Employed washing, cooking, cleaning the light. This is lonesome. We are all sick.

Alfred G. Eisener, a Maine native, became keeper in 1890. According to a newspaper account, the old dwelling when Eisener moved in was "very damp, and somewhat dilapidated." Funds were soon appropriated for the rebuilding of the dwelling, and for a new 45-foot stone lighthouse.

The design chosen for the new one-and-one-half-story, wood-frame keeper's house was the same as the design of a keeper's house built about the same time at Prospect Harbor, Maine. The first story contained a living room, dining room, kitchen, and pantry, and three bedrooms were located upstairs. A fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the new tower, presumably relocated from the old structure. The new light went into service in 1891.

Eisener moved on to Plymouth Light in 1894. A succession of keepers came and went over the next few decades; Eugene Terpeny stayed for the longest stretch (1894-1909). Terpeny's daughter, Alice Terpeny Petty, recalled her early life at the lighthouse many years later.

The 1891 lighthouse (U.S. Coast Guard)

She said that her father -- between visits of the government supply boat -- went to the village on the island to buy supplies and would bring them back in a wheelbarrow.

As many as 10 or 12 people would come to the house for Sunday dinners, and the Terpenys' island neighbors would often visit to play whist, to sew, or to dance. The visitors would bring lanterns to light the way on their return trip.

George Gustavus, a native of Wisconsin, was keeper from 1919 to 1926. Gustavus and his wife, Mabel, raised 10 children during their lighthouse years.

As many as 10 or 12 people would come to the house for Sunday dinners, and the Terpenys' island neighbors would often visit to play whist, to sew, or to dance. The visitors would bring lanterns to light the way on their return trip.

George Gustavus, a native of Wisconsin, was keeper from 1919 to 1926. Gustavus and his wife, Mabel, raised 10 children during their lighthouse years.

Gustavus's granddaughter Joan Kenworthy remembers her mother telling her about the August 1924 wreck of the Wanderer, the last whaling vessel out of New Bedford. The bark was blown into Sow and Pigs Reef near Cuttyhunk in a storm, and Joan's mother recalled "Keeper Gus" and residents of the island rescuing the crewmen and providing food and shelter.

Left: George Kezer was keeper 1909-11; this photo is courtesy of his granddaughter, Barbara Kezer.

Octave Ponsart, a New Bedford native and the son of Belgian immigrants, became keeper in 1943 and moved into the keeper's house with his wife, Emma, and their daughters, Bette and Seamond.

Years later, Seamond Ponsart Roberts fondly recalled the family's years at the Cuttyhunk Light Station. After hearing stories of the area's early English explorers, she loved to "play Gosnold."

Cuttyhunk Island was just a wonderful place for children. It was magic for sure. And it still is, I am glad to report. But the best magic was that my Daddy was a lighthouse keeper. He was just the best man and most patient father anyone could ever have, and he had this neat occupation that provided me with a lighthouse tower to play in and help care for. Besides playing Gosnold on the rocks, I would be the damsel in the tower or Rapunzel letting down her long hair in the fairy tale, even though my hair was brown and short. In my imagination I could do anything, and having a tower was a great accessory for my daydreams of fairy tales and dragons.

Octave Ponsart, a New Bedford native and the son of Belgian immigrants, became keeper in 1943 and moved into the keeper's house with his wife, Emma, and their daughters, Bette and Seamond.

Years later, Seamond Ponsart Roberts fondly recalled the family's years at the Cuttyhunk Light Station. After hearing stories of the area's early English explorers, she loved to "play Gosnold."

Cuttyhunk Island was just a wonderful place for children. It was magic for sure. And it still is, I am glad to report. But the best magic was that my Daddy was a lighthouse keeper. He was just the best man and most patient father anyone could ever have, and he had this neat occupation that provided me with a lighthouse tower to play in and help care for. Besides playing Gosnold on the rocks, I would be the damsel in the tower or Rapunzel letting down her long hair in the fairy tale, even though my hair was brown and short. In my imagination I could do anything, and having a tower was a great accessory for my daydreams of fairy tales and dragons.

The island for me as a kid was an endless playground.

I had the pond to play in with my little boats and floating toys. I had my chickens, which were my dear friends and providers of eggs and chicken dinners. I loved gathering eggs and this was my morning chore. I had a little garden and I always seemed to eat more baby carrots than I grew...

My father had so many duties connected with the little lighthouse on Cuttyhunk. He whitewashed and cleaned the tower, the house and the barn. He would polish the brass daily -- and there was a lot of brass. He would clean the lens, make sure the lamps (the main one and the spare one) were ready in the tower, and lots of other mundane stuff that went along with being a lighthouse keeper.

The crewmen from two local lightships -- the Vineyard Sound, and the Hen and Chickens -- often stopped at the Cuttyhunk Light Station on their way to or from their stations, and sometimes they spent the night on bunks provided by the Ponsarts. Seamond thought of the young men as uncles.

A hurricane on September 14, 1944, hit Cuttyhunk directly, changing the shape of the island. Ponsart weathered the storm and managed to keep the light going through the night, with the help of little Seamond, who ran up and down the stairs fetching supplies and coffee. As the wind reached its highest point, at about 2:00 a.m., there was a crash in the keeper's house -- a chimney had crashed through the roof. It landed on Seamond's bed, where she would have been sleeping if she hadn't been with her father.

Every night, the Ponsarts could see the lights of the Vineyard Sound lightship offshore.

My father had so many duties connected with the little lighthouse on Cuttyhunk. He whitewashed and cleaned the tower, the house and the barn. He would polish the brass daily -- and there was a lot of brass. He would clean the lens, make sure the lamps (the main one and the spare one) were ready in the tower, and lots of other mundane stuff that went along with being a lighthouse keeper.

The crewmen from two local lightships -- the Vineyard Sound, and the Hen and Chickens -- often stopped at the Cuttyhunk Light Station on their way to or from their stations, and sometimes they spent the night on bunks provided by the Ponsarts. Seamond thought of the young men as uncles.

A hurricane on September 14, 1944, hit Cuttyhunk directly, changing the shape of the island. Ponsart weathered the storm and managed to keep the light going through the night, with the help of little Seamond, who ran up and down the stairs fetching supplies and coffee. As the wind reached its highest point, at about 2:00 a.m., there was a crash in the keeper's house -- a chimney had crashed through the roof. It landed on Seamond's bed, where she would have been sleeping if she hadn't been with her father.

Every night, the Ponsarts could see the lights of the Vineyard Sound lightship offshore.

During the night of the hurricane, Seamond and her father checked periodically to see if the lightship could still be seen. The last time they saw it was around the time the chimney had fallen into the house.

Seamond later recalled:

Dad said to me, "Seamond, do you see the lightship?" And I did for a few seconds. Then, as we looked where the lights had been just seconds before, they were gone. When the next clear patch of sight came, no lights. We both knew. My father said, "The iron men in the iron ship, gone to the bottom."

The vessel went down with all hands, and all 12 crewmen on board were lost. Divers discovered the wreck of the lightship in 1963, and the ship's bronze fog bell was recovered. It was later incorporated into the U.S. Lightship Memorial on New Bedford's waterfront. Seamond Ponsart Roberts traveled from Louisiana to attend the memorial dedication.

The Ponsarts were still at Cuttyhunk Light in December of 1945 when the "Flying Santa," writer Edward Rowe Snow, dropped packages for the family from a plane. One package contained a doll for little Seamond. Unfortunately the doll was broken on the rocks, despite heavy packing. The girl was heartbroken.

Dad said to me, "Seamond, do you see the lightship?" And I did for a few seconds. Then, as we looked where the lights had been just seconds before, they were gone. When the next clear patch of sight came, no lights. We both knew. My father said, "The iron men in the iron ship, gone to the bottom."

The vessel went down with all hands, and all 12 crewmen on board were lost. Divers discovered the wreck of the lightship in 1963, and the ship's bronze fog bell was recovered. It was later incorporated into the U.S. Lightship Memorial on New Bedford's waterfront. Seamond Ponsart Roberts traveled from Louisiana to attend the memorial dedication.

The Ponsarts were still at Cuttyhunk Light in December of 1945 when the "Flying Santa," writer Edward Rowe Snow, dropped packages for the family from a plane. One package contained a doll for little Seamond. Unfortunately the doll was broken on the rocks, despite heavy packing. The girl was heartbroken.

|

The following Christmas the Ponsarts were stationed at West Chop Light on Martha's Vineyard. Edward Rowe Snow chartered a helicopter, flew to the island and handed a new doll to Seamond Ponsart.

Seamond later served in the Coast Guard herself, and she flew along with the Flying Santa as an "elf" in 2003. Right: Edward Rowe Snow as the Flying Santa hands a doll to Seamond Ponsart in 1946. |

|

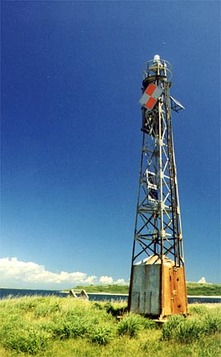

The lighthouse was torn down in 1947, replaced by a skeleton tower.

The keeper's house was also destroyed.

The skeleton tower (left) continues to exhibit a white flashing light, visible for 12 miles, from 63 feet above sea level.

Only a stone oil house remains from the light station, missing its door and roof.

A ferry from New Bedford will take you to Cuttyhunk. The island, which has a year-round population of under 100 people, is no longer worth visiting as a lighthouse destination, but is a fascinating place in its own right. There are good views of Martha's Vineyard's Gay Head cliffs from Cuttyhunk.

A round stone lookout tower stands as a monument to Gosnold's settlement. Octave Ponsart is buried on Cuttyhunk and a lighthouse is engraved on his gravestone.

The skeleton tower (left) continues to exhibit a white flashing light, visible for 12 miles, from 63 feet above sea level.

Only a stone oil house remains from the light station, missing its door and roof.

A ferry from New Bedford will take you to Cuttyhunk. The island, which has a year-round population of under 100 people, is no longer worth visiting as a lighthouse destination, but is a fascinating place in its own right. There are good views of Martha's Vineyard's Gay Head cliffs from Cuttyhunk.

A round stone lookout tower stands as a monument to Gosnold's settlement. Octave Ponsart is buried on Cuttyhunk and a lighthouse is engraved on his gravestone.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Benjamin Sayer (1822-c.1833); Nickerson Chase (c. 1833-1844); Fanny Chase (1844-1847); W.W. Goss (1847-1849); James Stubbs (1849-1853); Corbit Chandler (1853-1859); John B. Smith (1859-1864); S. Austin Smith (1864-1881), William Atchison (1881-1890); A. G. Eisener (1890-1894), John B. Carter (1894); Winfield L. Creed (189401896); Eugene Terpeny (1896-1909); Ella F. Terpeny (1909); George Kezer (1909-1911); L. B. Clark (1911-1917); George T. Gustavus (1919-1926); Harry Dobbins (1926-1936); Simeon A. Orne (1936-1943); Octave Ponsart (1943-1946).

Benjamin Sayer (1822-c.1833); Nickerson Chase (c. 1833-1844); Fanny Chase (1844-1847); W.W. Goss (1847-1849); James Stubbs (1849-1853); Corbit Chandler (1853-1859); John B. Smith (1859-1864); S. Austin Smith (1864-1881), William Atchison (1881-1890); A. G. Eisener (1890-1894), John B. Carter (1894); Winfield L. Creed (189401896); Eugene Terpeny (1896-1909); Ella F. Terpeny (1909); George Kezer (1909-1911); L. B. Clark (1911-1917); George T. Gustavus (1919-1926); Harry Dobbins (1926-1936); Simeon A. Orne (1936-1943); Octave Ponsart (1943-1946).