History of Stratford Point Lighthouse, Stratford, Connecticut

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Stratford was an active port in coastal trade, shipbuilding and oystering in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For years before there was a lighthouse, a bonfire and then a fire in an iron basket on a pole were used as aids to navigation at Stratford Point.

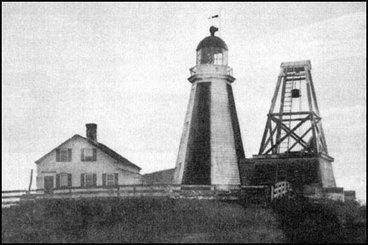

The first Stratford Point Lighthouse. (National Archives)

To mark the entrance to the harbor, the first Stratford Point Lighthouse was built on the west side of the dangerous mouth of the Housatonic River in 1822 at a cost of $4,000.

The revolving light consisted of 10 lamps and reflectors on two tables of five lamps each. In 1855, the 28-foot octagonal wooden tower was fitted with a fifth-order Fresnel lens. A fog bell in a bell tower was added in 1864. It took 20 minutes to wind the clockwork mechanism in the tower sufficiently for it to run for 30 minutes.

Stratford Point Light had a female keeper, Amy Buddington, for several years. An 1850 inspection mentioned that her son had taken over the care of the lighthouse.

The revolving light consisted of 10 lamps and reflectors on two tables of five lamps each. In 1855, the 28-foot octagonal wooden tower was fitted with a fifth-order Fresnel lens. A fog bell in a bell tower was added in 1864. It took 20 minutes to wind the clockwork mechanism in the tower sufficiently for it to run for 30 minutes.

Stratford Point Light had a female keeper, Amy Buddington, for several years. An 1850 inspection mentioned that her son had taken over the care of the lighthouse.

Stratford Point Light has often felt the brunt of storms, and the location is frequently foggy.

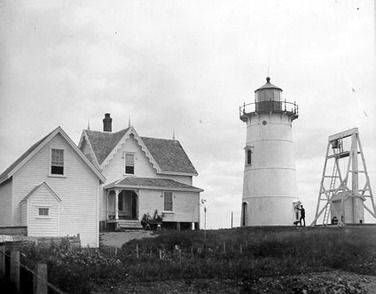

Stratford Point Light Station c. 1880s (U.S. Coast Guard )

Stratford Point Light has often felt the brunt of storms, and the location is frequently foggy. One keeper had to ring the fog bell for 32 consecutive hours, another rang it in a February storm for 104 hours, then another 103 hours after a brief rest.

In 1871, Benedict Lillingston was keeper and his son Frederick was assistant. In October, the keeper's granddaughter Lottie was visiting the lighthouse when the keepers had to go to the aid of a vessel in distress. Twelve-year old Lottie, left alone, noticed that the light had gone out. Lottie decided to put her knowledge gained from watching her uncle and grandfather into action.

Climbing to the lantern room by herself for the first time, Lottie lit a backup safety lamp and suspended it in place of the primary lamps. The captain of the steamer Elm Citynoticed the dim light showing as he passed the lighthouse.

By 1867 the original tower was in disrepair and the keeper's house was considered too small for a keeper and assistant. The authorities delayed rebuilding by appointing a married couple, Jerome and Mary Tuttle, as keeper and assistant. They were succeeded by another husband and wife, Theodore and Kate Judson. The present cast-iron tower, 35 feet tall, was finally built along with a new keeper's house in 1881.

In 1871, Benedict Lillingston was keeper and his son Frederick was assistant. In October, the keeper's granddaughter Lottie was visiting the lighthouse when the keepers had to go to the aid of a vessel in distress. Twelve-year old Lottie, left alone, noticed that the light had gone out. Lottie decided to put her knowledge gained from watching her uncle and grandfather into action.

Climbing to the lantern room by herself for the first time, Lottie lit a backup safety lamp and suspended it in place of the primary lamps. The captain of the steamer Elm Citynoticed the dim light showing as he passed the lighthouse.

By 1867 the original tower was in disrepair and the keeper's house was considered too small for a keeper and assistant. The authorities delayed rebuilding by appointing a married couple, Jerome and Mary Tuttle, as keeper and assistant. They were succeeded by another husband and wife, Theodore and Kate Judson. The present cast-iron tower, 35 feet tall, was finally built along with a new keeper's house in 1881.

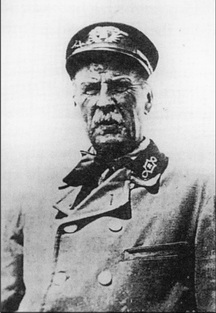

"Theed" Judson (right) was keeper from 1880 to 1921. It was said when Judson retired that he hadn't had a vacation in 39 years.

Judson once made an extraordinary claim in a local newspaper. He said that he had seen as many as 12 to 15 mermaids frolicking in the waves off the point. In fact, he said he once almost caught one of them, and he managed to salvage her oyster shell hairbrush. "They're a grand sight," he said of the mermaids. It's said that Judson's friends were never able to get him to retract the mermaid tale.

Agnes Judson, the keeper's daughter, gained fame as a swimmer who won competitions in the area. One summer day when she was 17, Agnes watched from the top of the lighthouse as the seas became increasingly rough. Two fishermen about 100 yards offshore were trying to pull up the anchor of their small yawl, and the waves caused both to fall into the sea.

Agnes ran down the lighthouse stairs. She called to her brother Henry, and both swam out to the fishermen. One of them was about to go under a second time when Agnes got a rope to him in the nick of time. Agnes and Henry managed to pull both of the men safely back to shore.

Judson once made an extraordinary claim in a local newspaper. He said that he had seen as many as 12 to 15 mermaids frolicking in the waves off the point. In fact, he said he once almost caught one of them, and he managed to salvage her oyster shell hairbrush. "They're a grand sight," he said of the mermaids. It's said that Judson's friends were never able to get him to retract the mermaid tale.

Agnes Judson, the keeper's daughter, gained fame as a swimmer who won competitions in the area. One summer day when she was 17, Agnes watched from the top of the lighthouse as the seas became increasingly rough. Two fishermen about 100 yards offshore were trying to pull up the anchor of their small yawl, and the waves caused both to fall into the sea.

Agnes ran down the lighthouse stairs. She called to her brother Henry, and both swam out to the fishermen. One of them was about to go under a second time when Agnes got a rope to him in the nick of time. Agnes and Henry managed to pull both of the men safely back to shore.

Stratford Point Light had a civilian keeper long after the Coast Guard took over at most lighthouses, a process that began in 1939.

U.S. Coast Guard photo c. 1960s

Daniel F. McCoart, a Providence native, Navy veteran and former light heavyweight boxer, was the civilian keeper from 1945 to 1963. He lived at the lighthouse with his family. William Shackley was the assistant keeper for many years, and he also lived in the keeper's house with his family. Keeper McCoart retired in 1963 after 44 years in the Lighthouse Service.

In 1969, Stratford Point Light took on the appearance of a "headless" lighthouse as the lantern was removed to make room for new automated DCB-224 aerobeacons. These powerful beacons for a time made the light the most powerful on Long Island Sound.

In 1969, Stratford Point Light took on the appearance of a "headless" lighthouse as the lantern was removed to make room for new automated DCB-224 aerobeacons. These powerful beacons for a time made the light the most powerful on Long Island Sound.

The old lantern was donated to the Stratford Historical Society, and it was displayed at Booth Memorial Park in Stratford for 21 years.

Stratford Point Light during its "headless" period (U.S. Coast Guard)

In 1990, a smaller optic was installed and the lantern was refurbished and reinstalled at a cost of about $80,000, with a dedication ceremony on July 14, 1990. The tower was repainted in 1996, keeping its distinctive markings of white with a brown band in the middle.

In June 2019, the Town of Stratford entered into a license agreement with the Coast Guard for the property. There are plans to provide more public access.

At this writing, the station is not open to the public. Views are possible from the gate.

In June 2019, the Town of Stratford entered into a license agreement with the Coast Guard for the property. There are plans to provide more public access.

At this writing, the station is not open to the public. Views are possible from the gate.

Inside the tower

Inside the tower

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Samuel Buddington (1821-c. 1841 and 1844-1848, died in service); William Merwin (c. 1841-1844); Amy Buddington (1848-1861); Rufus Buddington (1861-1869); Benedict Lillingston (1869-1874); Frederick Lillingston (assistant, c. 1869-1874); John L. Brush (1874-1879); Abigail Brush (assistant, 1874-1879); Jerome Tuttle (1879-1880); Mary Tuttle (assistant, 1879-1880); Theodore Judson (1880-1921); Kate Judson (assistant, 1880-1882); William Petzolt (assistant 1913-1921, keeper 1921-1945); Daniel F. McCoart (1945-1963); William A. Shackley (assistant, c. 1950s); Homer T. Nicholls

Samuel Buddington (1821-c. 1841 and 1844-1848, died in service); William Merwin (c. 1841-1844); Amy Buddington (1848-1861); Rufus Buddington (1861-1869); Benedict Lillingston (1869-1874); Frederick Lillingston (assistant, c. 1869-1874); John L. Brush (1874-1879); Abigail Brush (assistant, 1874-1879); Jerome Tuttle (1879-1880); Mary Tuttle (assistant, 1879-1880); Theodore Judson (1880-1921); Kate Judson (assistant, 1880-1882); William Petzolt (assistant 1913-1921, keeper 1921-1945); Daniel F. McCoart (1945-1963); William A. Shackley (assistant, c. 1950s); Homer T. Nicholls