History of Cleveland Ledge Lighthouse, Bourne, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Cleveland Ledge, west of Bourne in Buzzards Bay and eight miles southwest of the entrance to the Cape Cod Canal, is named for President Grover Cleveland, who frequently visited the area to fish in the days when his summer White House was at the Gray Gables mansion in Bourne.

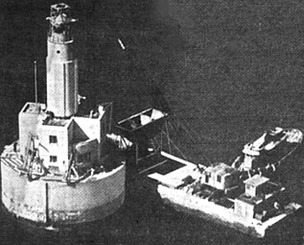

The construction of Cleveland Ledge Light. U.S. Coast Guard.

The unique tower built here was the last commissioned lighthouse in New England. The decision to build a lighthouse here was part of a plan to convert the aids to navigation in Buzzards Bay from their original purpose of serving local navigation to the new purpose of guiding major shipping traffic through the Cape Cod Canal, which opened in 1914.

The contract for the construction of the lighthouse was awarded to the J. F. Fitzgerald Company of Boston, in the amount of $198,851. On October 7, 1940, the caisson that would serve as the lighthouse's foundation was towed to the ledge from New London, Connecticut, where it had been constructed. The 52-foot- high caisson was sunk in 21 feet of water, and then filled with stone and concrete.

The contract for the construction of the lighthouse was awarded to the J. F. Fitzgerald Company of Boston, in the amount of $198,851. On October 7, 1940, the caisson that would serve as the lighthouse's foundation was towed to the ledge from New London, Connecticut, where it had been constructed. The 52-foot- high caisson was sunk in 21 feet of water, and then filled with stone and concrete.

Below the main deck were an engine room, fuel tanks, and four water tanks with a capacity of 4,800 gallons.

U.S. Coast Guard

On top of the caisson, a two-story building was constructed to house resident keepers, and this was surmounted by a 50-foot, reinforced-concrete light tower. The sleek architecture of the structure is classified as Art Moderne, a trendy style of the 1930s and 1940s.

After the onset of World War II, construction was delayed because of the shortage of many materials. The new lighthouse was completed and commissioned on June 1, 1943. It was put through a grueling test a little over a year later.

On September 14, 1944, a hurricane battered the area.

After the onset of World War II, construction was delayed because of the shortage of many materials. The new lighthouse was completed and commissioned on June 1, 1943. It was put through a grueling test a little over a year later.

On September 14, 1944, a hurricane battered the area.

When the storm hit, a crew comprised of nine men (and a dog) under the command of Lt. Ollie P. Swenson were in the lighthouse.

U.S. Coast Guard

A newspaper reported a few days later:

Every member of the crew will frankly admit today that he was surprised and, to put it mildly, gratified that the hitherto untried cement and steel structure withstood the storm. All had misgivings about their immediate futures at one time or another throughout that night, and during those hectic, fearful hours during which they alternately hoped and prayed that the next wave wouldn't be the one to bowl them all into the sea.

During the height of the storm, at about 12:30 a.m., a crash brought the entire crew running to an engine room in the lighthouse's base. A skylight had partially dislodged, and seawater was flooding the engine room. A barricade made of planks and mattresses stopped the water level from rising.

When the seas subsided slightly, two of the men, with lifelines around their waists, made it to the broken skylight and managed to plug the break with oil drums, mattresses, and planking.

Four men were assigned to the lighthouse at the time of a newspaper article in December 1967. Each of the men had two weeks at the station followed by a week off. When asked how the crew felt about spending their holidays at the lighthouse, the officer in charge, Ronald E. Glass of Birmingham, Alabama, said, “Of course, the men would rather be home, but you always look forward to going there when you are off. Everyone here understands our mission. We earn our liberty and eventually we get it.” That holiday season, two of the men got time off around Christmas while the other two were off at New Year’s.

Every member of the crew will frankly admit today that he was surprised and, to put it mildly, gratified that the hitherto untried cement and steel structure withstood the storm. All had misgivings about their immediate futures at one time or another throughout that night, and during those hectic, fearful hours during which they alternately hoped and prayed that the next wave wouldn't be the one to bowl them all into the sea.

During the height of the storm, at about 12:30 a.m., a crash brought the entire crew running to an engine room in the lighthouse's base. A skylight had partially dislodged, and seawater was flooding the engine room. A barricade made of planks and mattresses stopped the water level from rising.

When the seas subsided slightly, two of the men, with lifelines around their waists, made it to the broken skylight and managed to plug the break with oil drums, mattresses, and planking.

Four men were assigned to the lighthouse at the time of a newspaper article in December 1967. Each of the men had two weeks at the station followed by a week off. When asked how the crew felt about spending their holidays at the lighthouse, the officer in charge, Ronald E. Glass of Birmingham, Alabama, said, “Of course, the men would rather be home, but you always look forward to going there when you are off. Everyone here understands our mission. We earn our liberty and eventually we get it.” That holiday season, two of the men got time off around Christmas while the other two were off at New Year’s.

At the time of the 1967 article, the interior of the lighthouse was described as “spit and polish spotless,” and as “warm as toast” inside, thanks to a large oil furnace.

The living facilities included a galley, a lounge with a small television, sleeping quarters, and a lavatory. A 44-foot patrol boat from the Woods Hole Coast Guard station visited weekly with supplies, which were hauled up to the deck at the lighthouse in a sling

Click here for a photo of this lighthouse circa 1967-68, by BMC Stephen Prime.

The lighthouse originally had a fourth-order Fresnel lens, fueled by kerosene. In 1978, the lens was replaced and the light was automated, after the laying of an underwater cable to supply power. The Coast Guard crew was removed and the lighthouse was sealed off.

When he was a boy in the 1960s, James M. Howe of North Falmouth frequently visited the Coast Guard keepers at Cleveland Ledge, along with his two brothers. The men befriended the local boys. In 2005, with his good memories as an inspiration, Howe founded the Megansett Shores Lighthouse Foundation for the purpose of obtaining a lease for the lighthouse. Howe died in December 2005, but others pledged to carry on with the care of the lighthouse he loved.

In April 2007, it was announced that the lighthouse would be available to a suitable new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000.

No organizations applied for ownership, so the lighthouse was auctioned to the general public. Sandy Boyd, a California businessman, came out on top in December 2010 with a high bid of $190,000.

Click here for a photo of this lighthouse circa 1967-68, by BMC Stephen Prime.

The lighthouse originally had a fourth-order Fresnel lens, fueled by kerosene. In 1978, the lens was replaced and the light was automated, after the laying of an underwater cable to supply power. The Coast Guard crew was removed and the lighthouse was sealed off.

When he was a boy in the 1960s, James M. Howe of North Falmouth frequently visited the Coast Guard keepers at Cleveland Ledge, along with his two brothers. The men befriended the local boys. In 2005, with his good memories as an inspiration, Howe founded the Megansett Shores Lighthouse Foundation for the purpose of obtaining a lease for the lighthouse. Howe died in December 2005, but others pledged to carry on with the care of the lighthouse he loved.

In April 2007, it was announced that the lighthouse would be available to a suitable new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000.

No organizations applied for ownership, so the lighthouse was auctioned to the general public. Sandy Boyd, a California businessman, came out on top in December 2010 with a high bid of $190,000.