History of Seguin Island Light, near Georgetown, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

For more than two centuries, this lighthouse has been an important guide for mariners traveling along the Maine coast as well as those entering the Kennebec River toward Bath and other ports. Even earlier, high Seguin Island, rising more than 100 feet above the sea, was a prominent landmark. In August 1607, the English founders of the Popham colony anchored at the island before landing on the mainland.

When the explorer Samuel de Champlain sailed past Seguin Island in 1612, he commented that it looked like a giant tortoise. The name "Seguin" is said by some to be a corruption of an Indian word that means "place where the sea vomits." Others claim that it originates from an Indian word for "hump." Either way, it’s entirely appropriate.

Fifty-five local merchants petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts for a lighthouse on Seguin in June 1786. The petition noted that the “island Seguin seems to be designated by Nature for this purpose,” and it stated the opinion that “if there was a Light upon this Island many Vessels would be saved from Shipwreck, and many Persons preserved from immature Deaths.” At that time, there were only three light stations on the coast north of Boston: at Thacher Island off Cape Ann, at Portsmouth Harbor in New Hampshire, and at Portland Head in Maine.

Fifty-five local merchants petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts for a lighthouse on Seguin in June 1786. The petition noted that the “island Seguin seems to be designated by Nature for this purpose,” and it stated the opinion that “if there was a Light upon this Island many Vessels would be saved from Shipwreck, and many Persons preserved from immature Deaths.” At that time, there were only three light stations on the coast north of Boston: at Thacher Island off Cape Ann, at Portsmouth Harbor in New Hampshire, and at Portland Head in Maine.

Nearly a decade passed before the establishment of a light station was approved by President George Washington in May 1793.

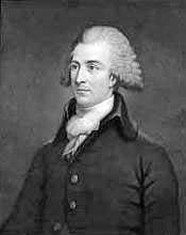

Tench Coxe

Ten acres of land on the island was ceded in February 1794 to the federal government by the State of Massachusetts, as Maine was part of Massachusetts at the time.

In June 1794, Commissioner of the Revenue Tench Coxe sent word to General Benjamin Lincoln, the customs collector and local lighthouse superintendent in Boston, that he should examine Seguin Island to select the most advantageous position for the lighthouse.

By April 1795, a site had been chosen and a request was posted in local newspapers for proposals to build an octagonal wooden lighthouse tower on a stone foundation and a one-story, wood-frame dwelling. A newspaper notice in late October 1796 announced that the buildings had been completed under the supervision of Henry Dearborn, who would later become the customs collector in Boston and secretary of War under President Jefferson.

Seguin’s first keeper, appointed in March 1796 at $200 per year, was Major John Polereczky, a Hungarian Hussar and count who was born in France and fought with French troops during the American Revolution. The Polereczky family had been Hungarian nobility as far back as 1613.

In June 1794, Commissioner of the Revenue Tench Coxe sent word to General Benjamin Lincoln, the customs collector and local lighthouse superintendent in Boston, that he should examine Seguin Island to select the most advantageous position for the lighthouse.

By April 1795, a site had been chosen and a request was posted in local newspapers for proposals to build an octagonal wooden lighthouse tower on a stone foundation and a one-story, wood-frame dwelling. A newspaper notice in late October 1796 announced that the buildings had been completed under the supervision of Henry Dearborn, who would later become the customs collector in Boston and secretary of War under President Jefferson.

Seguin’s first keeper, appointed in March 1796 at $200 per year, was Major John Polereczky, a Hungarian Hussar and count who was born in France and fought with French troops during the American Revolution. The Polereczky family had been Hungarian nobility as far back as 1613.

Polereczky settled in Dresden, Maine, after he resigned his commission, and he served for 25 years as town clerk, before and after his time on Seguin. In October 1795, Polereczky wrote to Benjamin Lincoln to express his desire for the keeper position “for the better support” of his family.

Benjamin Lincoln

“I am willing to sacrifice the pleasures of society,” he wrote, “to the fulfillment of the Duties of that office.” Polereczky obtained the keeper’s position as a reward for his war service, Henry Dearborn having served as his champion.

In May 1796, Polereczky wrote to Benjamin Lincoln to request a raise in pay. Revenue Commissioner Coxe, in charge of lighthouses, replied to Lincoln regarding the keeper’s request:

The house, the fuel, the land and the salary with the opportunities for fish would attract numbers of perfectly competent persons; tho perhaps few as respectable and of as much public merit as himself. But the fund assigned by law has been predicated upon strict ideas of what a keeper would merit, and could be engaged for, without difficulty. With these sentiments I do not at present propose to apply to the President to increase this salary.

In November 1796, Polereczky again requested a raise in his salary to $300. “I have but one Cow here for my family,” he wrote, “and one tun of haye I purchased for her, delivered to the house. Cost me 20 dolars and so it is with all the necessities of life till I Cann Raise them.”

In May 1796, Polereczky wrote to Benjamin Lincoln to request a raise in pay. Revenue Commissioner Coxe, in charge of lighthouses, replied to Lincoln regarding the keeper’s request:

The house, the fuel, the land and the salary with the opportunities for fish would attract numbers of perfectly competent persons; tho perhaps few as respectable and of as much public merit as himself. But the fund assigned by law has been predicated upon strict ideas of what a keeper would merit, and could be engaged for, without difficulty. With these sentiments I do not at present propose to apply to the President to increase this salary.

In November 1796, Polereczky again requested a raise in his salary to $300. “I have but one Cow here for my family,” he wrote, “and one tun of haye I purchased for her, delivered to the house. Cost me 20 dolars and so it is with all the necessities of life till I Cann Raise them.”

The raise was again denied. Polereczky served about eight years as keeper. His successor, Jonathan Delano, was appointed in October 1804. Like Polereczky, Delano often complained of the conditions on Seguin.

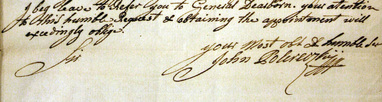

Part of one of Polereczky's letters. (National Archives)

In an 1809 letter, he wrote that the dwelling was very leaky and in great need of repair. When new lamps were installed in the lighthouse in 1812, Delano complained in a letter to the local superintendent that the lamps were defective.

The original tower had deteriorated and had to be rebuilt in 1819, this time of stone. The new lighthouse was much smaller than its predecessor; the specifications called for it to be 20 feet tall to the base of the lantern, 16 feet in diameter at the base, and 13 feet in diameter at the top.

The original tower had deteriorated and had to be rebuilt in 1819, this time of stone. The new lighthouse was much smaller than its predecessor; the specifications called for it to be 20 feet tall to the base of the lantern, 16 feet in diameter at the base, and 13 feet in diameter at the top.

A fog bell was added to the station in 1837. In his 1843 report to Congress, the engineer I. W. P. Lewis described the stone tower as in "bad order." Lewis noted that the old 1795 house was “in very good preservation” and was used for storage and as a “lodging-house.”

Nineteenth century engraving of Seguin Light Station

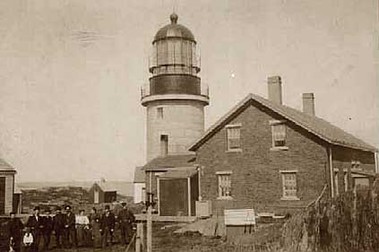

A new fog bell with automatic striking machinery was installed in 1854, and after an appropriation of $35,000, a new 53-foot stone tower was built in 1857. Because of the heavy maritime traffic in the area, a first-order Fresnel lens, Maine’s most powerful light, was installed in the lantern.

The nine-foot-high lens was large enough for the keepers to go completely inside it to light the lamp. A duplex keepers’ dwelling was also built in 1857.

Over a period of 31 years, the station was foggy 15 percent of the time. In 1907, the island set an all-time Maine mark for fogginess—2,374 hours, or about 31 percent of the year. The Lighthouse Board announced in 1870 that preparations had begun for the establishment of a new steam-driven fog signal to replace the bell. A new well was dug to provide the necessary water for the engines. A 10-inch steam whistle was installed by 1873, sounding one eight-second blast every minute.

Thomas Day became keeper 1875. Before becoming keeper, he had been captain of the Black Ball Liner Roanoke. When he retired as keeper in 1886, Day bought a farm in Bowdoinham, near Brunswick, Maine. In a 1942 interview in the Lewiston Journal, Day's grandson Joe York said:

I hated to leave the lighthouse. They used lard oil then in the lamps, and I can remember seeing grandfather with a big paddle stirring up the grease and preparing it for the lamp in the big lantern each night. Some different from the way old Portland Head is lighted now. But I never got interested in becoming a lightkeeper. I wanted to go to sea.

(Thanks to Charlie Kellogg for the information on Thomas Day.)

The nine-foot-high lens was large enough for the keepers to go completely inside it to light the lamp. A duplex keepers’ dwelling was also built in 1857.

Over a period of 31 years, the station was foggy 15 percent of the time. In 1907, the island set an all-time Maine mark for fogginess—2,374 hours, or about 31 percent of the year. The Lighthouse Board announced in 1870 that preparations had begun for the establishment of a new steam-driven fog signal to replace the bell. A new well was dug to provide the necessary water for the engines. A 10-inch steam whistle was installed by 1873, sounding one eight-second blast every minute.

Thomas Day became keeper 1875. Before becoming keeper, he had been captain of the Black Ball Liner Roanoke. When he retired as keeper in 1886, Day bought a farm in Bowdoinham, near Brunswick, Maine. In a 1942 interview in the Lewiston Journal, Day's grandson Joe York said:

I hated to leave the lighthouse. They used lard oil then in the lamps, and I can remember seeing grandfather with a big paddle stirring up the grease and preparing it for the lamp in the big lantern each night. Some different from the way old Portland Head is lighted now. But I never got interested in becoming a lightkeeper. I wanted to go to sea.

(Thanks to Charlie Kellogg for the information on Thomas Day.)

Because of the steep quarter-mile climb up to the lighthouse, a tramway system was installed in 1895, its tracks leading from the boathouse up to the keepers’ house. Supplies were loaded into a car that was brought up more than 1,000 feet on the tracks by means of a hoisting engine.

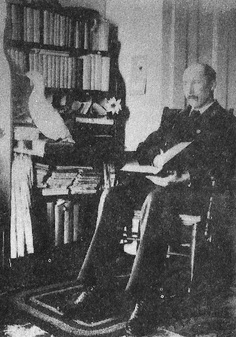

Herbert Spinney (Friends of Seguin Island)

A 1904 Boston Globe article profiled Herbert Spinney, who had been an assistant keeper beginning in 1893 and was principal keeper from 1903 to 1907. Spinney, who was a native of nearby Georgetown, Maine, also served as president of the Maine Ornithological Society. He had collected and mounted birds since boyhood, and he also collected birds’ eggs, butterflies, minerals, and corals. He always carried a camera, and he developed and printed his own photos.

Spinney’s collection filled much of the dwelling’s wall space from floor to ceiling. This makeshift museum drew increasing numbers of visitors to the island, and eventually the keeper began charging an admission fee of a dime to keep the crowds more manageable.

Included in the collection was a stuffed monkey, and a visitor once asked the keeper if he had shot the monkey on the island. “No madam,” replied Spinney, “I didn’t, but I’ve seen little monkeys on this island that I should like to shoot.”

Many of the birds Spinney collected were found dead after flying into the lantern glass of the tower. On one memorable morning, Spinney found 275 birds dead around the lighthouse.

Spinney kept a journal of his observations; here’s the entry for September 3, 1899:

Spinney’s collection filled much of the dwelling’s wall space from floor to ceiling. This makeshift museum drew increasing numbers of visitors to the island, and eventually the keeper began charging an admission fee of a dime to keep the crowds more manageable.

Included in the collection was a stuffed monkey, and a visitor once asked the keeper if he had shot the monkey on the island. “No madam,” replied Spinney, “I didn’t, but I’ve seen little monkeys on this island that I should like to shoot.”

Many of the birds Spinney collected were found dead after flying into the lantern glass of the tower. On one memorable morning, Spinney found 275 birds dead around the lighthouse.

Spinney kept a journal of his observations; here’s the entry for September 3, 1899:

Midnight, wind northwest, very dark, not a star to be seen; the air so impregnated with smoke as to make my throat smart in breathing; at this hour I came on duty, the birds were flying around the light; on going into the lantern I found about 75 birds on the outside; pine warblers, black and white yellow throats, oven birds, two hermit thrushes and one yellow-bellied flycatcher; all seemed to alight on the glass as fast as they appeared; very few seen flying around the light.

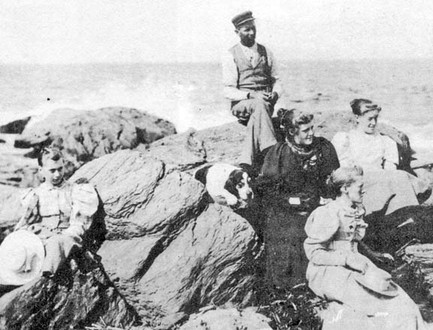

Herbert Spinney and family in 1898 (Friends of Seguin Island)

At 3 a.m. came a light shower, which seemed to check the flight. Those on the lantern remained until morning. All the mortality occurred with the yellow throats, 10 of this species being found dead. This seems odd, as I could hear many birds strike the dome of the lantern, the concussion when they struck sounding like a body of several hundred pounds weight.

Elson Small, previously at Lubec Channel Light and Avery Rock, was keeper from 1926 to 1930. His wife, Connie, later wrote the book The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife, in which she painted a vivid portrait of life on Seguin.

In her book, Connie Small recalled spirited sing-alongs and wrestling matches between the keepers and visiting work crews. Elson Small played banjo, accordion, guitar, and harmonica, and Connie played the piano. A visiting crew sent to work on the island’s tramway included Howard Colbath, a carpenter who played the fiddle. At the same time, the fog signal engines were being repaired by Fred Morong, a machinist with a fine baritone singing voice. As the band played, the three daughters of assistant keeper Frank Bracey danced the Charleston.

Elson Small, previously at Lubec Channel Light and Avery Rock, was keeper from 1926 to 1930. His wife, Connie, later wrote the book The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife, in which she painted a vivid portrait of life on Seguin.

In her book, Connie Small recalled spirited sing-alongs and wrestling matches between the keepers and visiting work crews. Elson Small played banjo, accordion, guitar, and harmonica, and Connie played the piano. A visiting crew sent to work on the island’s tramway included Howard Colbath, a carpenter who played the fiddle. At the same time, the fog signal engines were being repaired by Fred Morong, a machinist with a fine baritone singing voice. As the band played, the three daughters of assistant keeper Frank Bracey danced the Charleston.

Left and right, above: Connie Small, in an interview recorded when she was 96 years old, recalls life at Seguin Island.

Frank Bracey, who had been a crewman on the Portland Lightship, was one of the keepers in the 1920s and 1930s. He claimed to have seen seagulls knocked from the air by the concussion of the foghorn, which on at least one occasion was heard as far away as Bath, 14 miles distant.

Connie and Elson Small

Bracey also told the historian Edward Rowe Snow that he witnessed the fog signal extinguish an oil lantern on the ground eight feet below the horn.

As befits a remote lighthouse location, Seguin Island has ghost stories galore. Keepers spoke of furniture moving on its own and doors slamming themselves.

A popular tale concerns a nineteenth-century keeper’s wife who played the same tune over and over on her piano. The keeper was eventually driven insane and destroyed the piano with an axe, then killed his wife and himself.

Legend has it that the piano tune can still be heard drifting from the island on calm nights. Some local people have attributed the story to nearby Pond Island.

The Maine writer William O. Thomson claims that Coast Guard keepers told him about the specter of a young girl they saw running and laughing in the house—the ghost, it’s said, of a keeper’s daughter who died on the island. Other keepers have reported doors opening and closing themselves and mysterious coughing not produced by any of the keepers.

As befits a remote lighthouse location, Seguin Island has ghost stories galore. Keepers spoke of furniture moving on its own and doors slamming themselves.

A popular tale concerns a nineteenth-century keeper’s wife who played the same tune over and over on her piano. The keeper was eventually driven insane and destroyed the piano with an axe, then killed his wife and himself.

Legend has it that the piano tune can still be heard drifting from the island on calm nights. Some local people have attributed the story to nearby Pond Island.

The Maine writer William O. Thomson claims that Coast Guard keepers told him about the specter of a young girl they saw running and laughing in the house—the ghost, it’s said, of a keeper’s daughter who died on the island. Other keepers have reported doors opening and closing themselves and mysterious coughing not produced by any of the keepers.

The last civilian keeper on Seguin was Clarence Skolfield, a former merchant mariner who arrived as third assistant keeper in 1936 and left as the very popular principal keeper in 1946.

Skolfield later became keeper at Perkins Island Light and Squirrel Point Light, retiring in 1966.

Skolfield’s son, Tom, became a lobsterman in Cape Elizabeth. He later remembered his days at Seguin fondly. “It was perfect there, like being Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn,” he told Down East magazine.

One of the keepers kept two cows and a bull on the island. The bull was allowed to run loose, and it sometimes charged at Tom Skolfield’s sister.

The Skolfields’ complaints yielded no results, so the next time the bull came near their residence, Tom’s father fired a shotgun into the air. The bull ran to a far corner of the island and never bothered them again. “The bull was scared of Dad,” said Tom.

Skolfield’s son, Tom, became a lobsterman in Cape Elizabeth. He later remembered his days at Seguin fondly. “It was perfect there, like being Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn,” he told Down East magazine.

One of the keepers kept two cows and a bull on the island. The bull was allowed to run loose, and it sometimes charged at Tom Skolfield’s sister.

The Skolfields’ complaints yielded no results, so the next time the bull came near their residence, Tom’s father fired a shotgun into the air. The bull ran to a far corner of the island and never bothered them again. “The bull was scared of Dad,” said Tom.

The tramway built to help the keepers get supplies up the steep slope to the station was generally a great help, but it proved dangerous on at least one occasion.

Clarence Skolfield

In September 1949, one of the keepers, Daniel Irvine, was riding the car uphill with his 22-year-old wife Joyce and their two children, 18-month-old Daniel, Jr., and two-month old Millie. Something went wrong and the car reversed direction and began to hurtle back down the hill.

Irvine grabbed Mille and jumped out onto the grass, shouting for his wife to do the same with Daniel, Jr. She tossed the baby into high grass that cushioned his fall, but by the time she was ready to jump the car was moving too fast and was too high above the ground. The wheels left the tracks and the car continued at high speed down the hill, where it came to a violent stop that resulted in Joyce Irvine suffering a leg fracture.

The family dog was killed in the unfortunate incident, and from that point, the Coast Guard didn’t allow passengers on the tramway.

Irvine grabbed Mille and jumped out onto the grass, shouting for his wife to do the same with Daniel, Jr. She tossed the baby into high grass that cushioned his fall, but by the time she was ready to jump the car was moving too fast and was too high above the ground. The wheels left the tracks and the car continued at high speed down the hill, where it came to a violent stop that resulted in Joyce Irvine suffering a leg fracture.

The family dog was killed in the unfortunate incident, and from that point, the Coast Guard didn’t allow passengers on the tramway.

Seguin became a males-only station in 1963. The last keeper whose family lived on the island was George F. Johns of Bath.

Right: This magneto phone was used to call the keeper's house from the boathouse.

There were two other crewmen and their families, with a total of five children living at the station. Mrs. Johns said she never dared let their two little girls out of her sight because of the high precipices on the island. The family was the last to live in the 1876 assistant keeper’s house, which was subsequently demolished.

After the families left, four Coast Guard keepers were assigned to the station; three were on the island and one was on shore leave at all times. Some took to island living more easily than others. Kenneth Estey, who spent two years on the island in the early 1980s, told a local newspaper, “Sometimes I don’t know if I should eat—if I’m hungry or just bored.” Estey said he passed his time by reading Mark Twain or science fiction. Another keeper at the time, Eric Thompson, enjoyed target shooting on the island.

There were two other crewmen and their families, with a total of five children living at the station. Mrs. Johns said she never dared let their two little girls out of her sight because of the high precipices on the island. The family was the last to live in the 1876 assistant keeper’s house, which was subsequently demolished.

After the families left, four Coast Guard keepers were assigned to the station; three were on the island and one was on shore leave at all times. Some took to island living more easily than others. Kenneth Estey, who spent two years on the island in the early 1980s, told a local newspaper, “Sometimes I don’t know if I should eat—if I’m hungry or just bored.” Estey said he passed his time by reading Mark Twain or science fiction. Another keeper at the time, Eric Thompson, enjoyed target shooting on the island.

The light was automated in 1985 and the keepers were removed. The last Coast Guard keeper was First Class Boatswain Mate Edward T. Brown, who hated leaving Seguin. "I'd stand on my head to live on the island with my family," he said.

The iron spiral stairway in the tower

A ghostly story about the automation of Seguin Island Light, related by the lighthouse historian William O. Thomson, concerns the crew that arrived to take all the furniture from the keeper’s house. They packed up most of the furniture and spent the night in the keeper’s house, planning to leave in the morning.

The officer in charge later claimed that he was rudely awakened by a figure standing in front of him, pleading, “Don’t take the furniture. Please leave my home alone!” The next day the crew went ahead and loaded the furniture into a boat. Suddenly the chain holding the boat broke, the engine stopped, and the boat sank with all the furniture.

After automation, the future of the station was uncertain. Concerned local citizens led by a real estate broker, Anne Webster, founded the Friends of Seguin Island in 1986. Three years later the Friends of Seguin Island received a 10-year lease on the property from the Coast Guard. In February 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the property was transferred to the group.

The officer in charge later claimed that he was rudely awakened by a figure standing in front of him, pleading, “Don’t take the furniture. Please leave my home alone!” The next day the crew went ahead and loaded the furniture into a boat. Suddenly the chain holding the boat broke, the engine stopped, and the boat sank with all the furniture.

After automation, the future of the station was uncertain. Concerned local citizens led by a real estate broker, Anne Webster, founded the Friends of Seguin Island in 1986. Three years later the Friends of Seguin Island received a 10-year lease on the property from the Coast Guard. In February 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the property was transferred to the group.

Grants and donations paid for the restoration of the keeper’s house. Since 1990, caretakers have lived at Seguin in the summer.

The caretakers in the summer of 1996 were Harry Denker, a carpenter and contractor from Ontario, his wife, Lawrene, a writer, and their two daughters, Rachael and Anna. Harry Denker explained his attraction to Seguin to the Bath Times-Record: “The lighthouse comes across to me as something stable, something the mariners can count on. It’s a reassuring thing.” Since the summer of 1996, the Denkers have returned almost every spring to help get things ready for the summer season.

Right: The Denkers family of Ontario spent the summer of 1996 on Seguin Island as the caretakers, and returned most years for many years after that to help get things ready for the summer season. This photo of Lawrene, Rachael, and Harry Denkers was taken in May 2005.

Right: The Denkers family of Ontario spent the summer of 1996 on Seguin Island as the caretakers, and returned most years for many years after that to help get things ready for the summer season. This photo of Lawrene, Rachael, and Harry Denkers was taken in May 2005.

Nick and Stasi Bottinelli of Denver, Colorado, were the caretakers for the summer of 1997.

The 2001 caretakers, Jim Woods and Kris Pescatore of Boulder, Colorado

Stasi wrote in the logbook:

We are both so excited every time we open the door and go outside because the weather is always interesting and pleasant in one way or another... The air is full of the smell of wild roses, green grass, sea mists, all the blooming and ripening things. The sounds of the catbirds and warblers bring such peaceful delight, especially near dusk on the main trail near the tramway.

In February 1998, the Coast Guard announced plans to replace Seguin's first-order Fresnel lens with a modern solar-powered plastic optic.

The Coast Guard said that it was too expensive to maintain the 17,000-foot underwater cable necessary to run the light inside the large lens, so they would have saved taxpayers' dollars by replacing it.

We are both so excited every time we open the door and go outside because the weather is always interesting and pleasant in one way or another... The air is full of the smell of wild roses, green grass, sea mists, all the blooming and ripening things. The sounds of the catbirds and warblers bring such peaceful delight, especially near dusk on the main trail near the tramway.

In February 1998, the Coast Guard announced plans to replace Seguin's first-order Fresnel lens with a modern solar-powered plastic optic.

The Coast Guard said that it was too expensive to maintain the 17,000-foot underwater cable necessary to run the light inside the large lens, so they would have saved taxpayers' dollars by replacing it.

The Friends of Seguin Island wanted the lens to remain in the lighthouse; it's the only operating first-order Fresnel lens in Maine. The Coast Guard did offer an alternative: leaving the lens in place but not active, replacing it by erecting a solar powered light on a nearby mast.

A look inside the lens

The Friends mounted a petition drive to convince the Coast Guard to leave the historic lens in operation. They collected more than 7,200 signatures.

In March 2000, Sen. Olympia Snowe of Maine announced that the Coast Guard had agreed to leave the lens in operation. Senator Snowe said in a press release:

Seguin Island light remains the only operational [first order] Fresnel lens north of Rhode Island, and the Coast Guard's decision will assure that this historic light will remain working into the new millennium, consistent with this historic lighthouse.

Captain Bob Papp, chief of congressional affairs for the Coast Guard, told the Portland Press Herald, "The Coast Guard is in the service of the taxpayer. We came up with the best plan we could, but it may not fit every situation. We made an exception in this case."

Jim Woodward, one of the nation's leading "lampists," or lighthouse lens experts, went to the island in May 2005 to have a close look at the lens. The expansion and contraction in the tower over the years, caused by temperature variations and high winds, was being absorbed by the lens, causing damage.

Later in 2005, lens experts Joe Cocking, Nick Johnston, and Jim Dunlop went to Seguin to examine the lens. The Coast Guard awarded the contract for the restoration of the lens in June 2006 to Lighthouse Lamp Shop, Inc., owned by Joe Cocking, a retired Coast Guard chief warrant officer.

In March 2000, Sen. Olympia Snowe of Maine announced that the Coast Guard had agreed to leave the lens in operation. Senator Snowe said in a press release:

Seguin Island light remains the only operational [first order] Fresnel lens north of Rhode Island, and the Coast Guard's decision will assure that this historic light will remain working into the new millennium, consistent with this historic lighthouse.

Captain Bob Papp, chief of congressional affairs for the Coast Guard, told the Portland Press Herald, "The Coast Guard is in the service of the taxpayer. We came up with the best plan we could, but it may not fit every situation. We made an exception in this case."

Jim Woodward, one of the nation's leading "lampists," or lighthouse lens experts, went to the island in May 2005 to have a close look at the lens. The expansion and contraction in the tower over the years, caused by temperature variations and high winds, was being absorbed by the lens, causing damage.

Later in 2005, lens experts Joe Cocking, Nick Johnston, and Jim Dunlop went to Seguin to examine the lens. The Coast Guard awarded the contract for the restoration of the lens in June 2006 to Lighthouse Lamp Shop, Inc., owned by Joe Cocking, a retired Coast Guard chief warrant officer.

The restoration project began in July 2006. Cocking and Nick Johnston repaired and re-installed two damaged central prisms. The lens's frame and the lens itself were cleaned and corrosive contaminants were removed. Cracks were repaired and the lens was polished.

You can drive to Popham Beach for distant views of Seguin Light -- bring your binoculars. Better yet, you can visit Seguin Island Light by boat. For lovers of lighthouses teeming with legends and lore, this is a must.

For more information about visiting Seguin Island, or to donate to the maintenance of the property, contact Friends of Seguin Island.

Keepers: (The following list of keepers is not complete. It is a work in progress, and any additional information is welcomed and appreciated; you can email me at [email protected]. If you copy this list to another site, you do so at your own risk. I can't guarantee its accuracy.)

John Polereszky (1796-1804); Christopher Pushard (assistant, c.1796-1804); John Hollaway (assistant? c.1800); Jonathan Delano (1804-1825); John Salter (1825-1839); Nathaniel Springer Todd (1839-1849); James Marston (1849-1853); A. E. Osgood (1853-1857); Boyd L. Miles (assistant, 1855); Joseph King (assistant, 1855); Stephen Marston Jr. (1857); Daniel Dodge (1857); John C. Lowell (1857-1859); Granville Lowell (1859-1861); Tallman B. Lowell (assistant, 1859-1860); William M. Knight (1860-1861); Zina H. Spinney (1861-1866); P. O. Spinney (assistant, 1861-1865); David Spinney 2nd (assistant, 1861-1863); David Spinney (assistant, 1863-1865); Rachel Spinney (assistant, 1865-1866); William S. Oliver (assistant, 1865-1866); Francis L. Morrill (1866-1868); William C. Marr (assistant, 1866); Ephraim S. Marr (assistant, 1866 and 1874-1875); Henry E. Morrill (1866-1867); Charles S. Morrill (assistant, 1866-1867); Jane Morrill (assistant, 1867-1869); Arthur Hutchins (assistant, 1867-1869); Samuel (Lemuel?) G. Crane (1867-1875); O. B. Crane (assistant, 1868-1871); J. B. Crane (assistant, 1868-1974); Louisa N. Lane (Crane?) (assistant, 1871-1872); Turner Jewett (assistant, 1872); Elisha B. Crane (assistant, 1874-1875); Thomas Day (1875-1886); Thomas Bibber (assistant, 1876-1880); Willis E. Chase (assistant, 1875); Henry Wiley (assistant, 1881-1882); Samuel Cavanor (assistant, 1882); Fernando Wallace (assistant, 1882-1886); Edwin M. Wyman (assistant, 1886-1889); Henry Day (1886-1890); Henry M. Clark (assistant, 1887); William H. Wyman (assistant, 1888-1889); Jesse Pierce (assistant, 1889); Merritt P. Pinkham (assistant 1889-1890, head keeper 1890-1898); Parker O. Healey (assistant, 1890-1893); William A. Stetson (assistant 1898); Fred Hodgkins (assistant, 1903); George A. Lewis (1898-1903 and 1907-1912 - died 1/6/1912); Herbert L. Spinney (assistant 1893-1898, head keeper 1903-1907); Walter S. Adams (assistant, 1907-1908); Clifford B. Staples (assistant, 1908-1912); Henry M. Cuskley (1912-1915); Maurice M. Weaver (1915-1922); Robert Thayer Sterling (assistant, somewhere between 1915 and 1928); Vinal Beal (first assistant, 1921-1924); Arthur Marston (assistant? 1921-1923); Napoleon B. Fickett (1922-1926); Elson L. Small (1926-1930); Frank E. Bracey (assistant 1926-1930, head keeper 1930-1931); Millard H. Urquhart (assistant 1928-1931, head keeper 1931-1938); Jasper L. Cheney (assistant, 1930-1931); Joseph M. Conners (assistant, 1931-1936); Donald E. Robbins, assistant (1930-1932); Clinton L. Dalzell (assistant, 1932-1933); Floyd Ettinger Singer (assistant, 1932-1933); Truman L. Lathrop (assistant, 1933-1934); Benjamin Stockbridge (assistant, 1934); Ernest F. Witty (assistant, 1935); George A. McKenney (assistant, 1935-1936); Clarence Skolfield (assistant, 1936-1944; principal keeper 1944-1946); Arthur G. Hill (assistant, 1936-1938); Maxwell A. DeShon (assistant, 1938-1941); Alton S, Chaney (Coast Guard, 1939-1944); Herbert Mitchell (Coast Guard assistant, 1940-1944); Archie McLaughlin (Coast Guard assistant, 1944-1945); Robert J. Werner (Coast Guard assistant, 1944-1945); Irving Dobbins (Coast Guard assistant, 1944); Alonzo Morong (Coast Guard, 1946-1950); Clyde T. Whittaker (Coast Guard,1948-1951); Edgar M. Wallace (Coast Guard,1949-1950); Daniel Irvine (Coast Guard assistant, 1949-1950); ? Bardsley (c. 1950); David Morrison (c. 1950-?); Harvey Lamson (Coast Guard,1951-1952); Harry Leighton Cressey (Coast Guard assistant,1947-1951, officer in charge 1951-1954); Horace Smith (Coast Guard assistant, 1953); Douglas Cameron (Coast Guard assistant, 1953); Charles Balsdon (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1953); Francis Manzie (Manzi) (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1953-1954); Mac McKinley (Coast Guard, c. 1955); Charles A. Hart Jr. (Coast Guard assistant, 1955); George F. Barnes (Coast Guard assistant, c, 1956); Marshall Witherell (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1956); ? Farrington (Coast Guard, c. 1958); John Johnston (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1959); Walter Stephens (Coast Guard, 1959-1960); Ronald D. Howard (Coast Guard, 1960-1961); James R. Wilson (Coast Guard,1961); Kenneth J. Dukes (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1962); George F. Johns (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); William B. O'Neill (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); Timothy Flaherty (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); Henry LeBlanc (Coast Guard,1963); Fred Kahrl (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Robert Bly (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Elwynne Kenny (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Robert Grindall (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1966-1968); Timothy Bailey (c. 1974); Henry Lipian (Coast Guard, 1976); Oreta Bridgeman (Coast Guard assistant, 1976); Henry Lipian (Coast Guard officer in charge Feb. 1976-Feb. 1977); Edward T. Brown (Coast Guard,1983-1985); Lamar Alexander (Coast Guard assistant, 1986).

For more information about visiting Seguin Island, or to donate to the maintenance of the property, contact Friends of Seguin Island.

Keepers: (The following list of keepers is not complete. It is a work in progress, and any additional information is welcomed and appreciated; you can email me at [email protected]. If you copy this list to another site, you do so at your own risk. I can't guarantee its accuracy.)

John Polereszky (1796-1804); Christopher Pushard (assistant, c.1796-1804); John Hollaway (assistant? c.1800); Jonathan Delano (1804-1825); John Salter (1825-1839); Nathaniel Springer Todd (1839-1849); James Marston (1849-1853); A. E. Osgood (1853-1857); Boyd L. Miles (assistant, 1855); Joseph King (assistant, 1855); Stephen Marston Jr. (1857); Daniel Dodge (1857); John C. Lowell (1857-1859); Granville Lowell (1859-1861); Tallman B. Lowell (assistant, 1859-1860); William M. Knight (1860-1861); Zina H. Spinney (1861-1866); P. O. Spinney (assistant, 1861-1865); David Spinney 2nd (assistant, 1861-1863); David Spinney (assistant, 1863-1865); Rachel Spinney (assistant, 1865-1866); William S. Oliver (assistant, 1865-1866); Francis L. Morrill (1866-1868); William C. Marr (assistant, 1866); Ephraim S. Marr (assistant, 1866 and 1874-1875); Henry E. Morrill (1866-1867); Charles S. Morrill (assistant, 1866-1867); Jane Morrill (assistant, 1867-1869); Arthur Hutchins (assistant, 1867-1869); Samuel (Lemuel?) G. Crane (1867-1875); O. B. Crane (assistant, 1868-1871); J. B. Crane (assistant, 1868-1974); Louisa N. Lane (Crane?) (assistant, 1871-1872); Turner Jewett (assistant, 1872); Elisha B. Crane (assistant, 1874-1875); Thomas Day (1875-1886); Thomas Bibber (assistant, 1876-1880); Willis E. Chase (assistant, 1875); Henry Wiley (assistant, 1881-1882); Samuel Cavanor (assistant, 1882); Fernando Wallace (assistant, 1882-1886); Edwin M. Wyman (assistant, 1886-1889); Henry Day (1886-1890); Henry M. Clark (assistant, 1887); William H. Wyman (assistant, 1888-1889); Jesse Pierce (assistant, 1889); Merritt P. Pinkham (assistant 1889-1890, head keeper 1890-1898); Parker O. Healey (assistant, 1890-1893); William A. Stetson (assistant 1898); Fred Hodgkins (assistant, 1903); George A. Lewis (1898-1903 and 1907-1912 - died 1/6/1912); Herbert L. Spinney (assistant 1893-1898, head keeper 1903-1907); Walter S. Adams (assistant, 1907-1908); Clifford B. Staples (assistant, 1908-1912); Henry M. Cuskley (1912-1915); Maurice M. Weaver (1915-1922); Robert Thayer Sterling (assistant, somewhere between 1915 and 1928); Vinal Beal (first assistant, 1921-1924); Arthur Marston (assistant? 1921-1923); Napoleon B. Fickett (1922-1926); Elson L. Small (1926-1930); Frank E. Bracey (assistant 1926-1930, head keeper 1930-1931); Millard H. Urquhart (assistant 1928-1931, head keeper 1931-1938); Jasper L. Cheney (assistant, 1930-1931); Joseph M. Conners (assistant, 1931-1936); Donald E. Robbins, assistant (1930-1932); Clinton L. Dalzell (assistant, 1932-1933); Floyd Ettinger Singer (assistant, 1932-1933); Truman L. Lathrop (assistant, 1933-1934); Benjamin Stockbridge (assistant, 1934); Ernest F. Witty (assistant, 1935); George A. McKenney (assistant, 1935-1936); Clarence Skolfield (assistant, 1936-1944; principal keeper 1944-1946); Arthur G. Hill (assistant, 1936-1938); Maxwell A. DeShon (assistant, 1938-1941); Alton S, Chaney (Coast Guard, 1939-1944); Herbert Mitchell (Coast Guard assistant, 1940-1944); Archie McLaughlin (Coast Guard assistant, 1944-1945); Robert J. Werner (Coast Guard assistant, 1944-1945); Irving Dobbins (Coast Guard assistant, 1944); Alonzo Morong (Coast Guard, 1946-1950); Clyde T. Whittaker (Coast Guard,1948-1951); Edgar M. Wallace (Coast Guard,1949-1950); Daniel Irvine (Coast Guard assistant, 1949-1950); ? Bardsley (c. 1950); David Morrison (c. 1950-?); Harvey Lamson (Coast Guard,1951-1952); Harry Leighton Cressey (Coast Guard assistant,1947-1951, officer in charge 1951-1954); Horace Smith (Coast Guard assistant, 1953); Douglas Cameron (Coast Guard assistant, 1953); Charles Balsdon (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1953); Francis Manzie (Manzi) (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1953-1954); Mac McKinley (Coast Guard, c. 1955); Charles A. Hart Jr. (Coast Guard assistant, 1955); George F. Barnes (Coast Guard assistant, c, 1956); Marshall Witherell (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1956); ? Farrington (Coast Guard, c. 1958); John Johnston (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1959); Walter Stephens (Coast Guard, 1959-1960); Ronald D. Howard (Coast Guard, 1960-1961); James R. Wilson (Coast Guard,1961); Kenneth J. Dukes (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1962); George F. Johns (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); William B. O'Neill (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); Timothy Flaherty (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1963); Henry LeBlanc (Coast Guard,1963); Fred Kahrl (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Robert Bly (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Elwynne Kenny (Coast Guard,1966-1967); Robert Grindall (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1966-1968); Timothy Bailey (c. 1974); Henry Lipian (Coast Guard, 1976); Oreta Bridgeman (Coast Guard assistant, 1976); Henry Lipian (Coast Guard officer in charge Feb. 1976-Feb. 1977); Edward T. Brown (Coast Guard,1983-1985); Lamar Alexander (Coast Guard assistant, 1986).