History of Deer Island Light, Boston Harbor, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Two-hundred-ten-acre Deer Island in Boston Harbor, south of the town of Winthrop, served as an internment camp for Indians in 1675 during King Philip's War. Later, it was the site of a quarantine station where many immigrants died, a hospital, an almshouse, a fort, and a state prison.

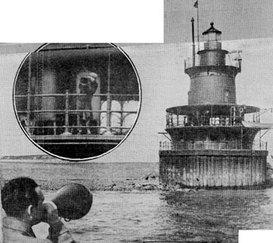

From Stebbins' Illustrated Coast Pilot 1902

Today, the island is home to a massive sewage treatment plant for the Boston area. Deer Island ceased being an island in the 1930s, when Shirley Gut, which previously separated it from Winthrop, was filled in.

In 1832, the Boston Marine Society petitioned Congress for $3,000 for the placement of an unlighted stone beacon at Deer Island Point, at the north side of the entrance to Boston's inner harbor and about 500 yards south of the island's southeasterly point. This marker served as a navigational aid for almost 60 years.

In the annual reports for 1884 and 1885, the Lighthouse Board stated the following:

The steamers plying between Boston and the northern ports make use of the Broad Sound channels, and a light and fog-signal at this point are particularly desirable, because of the narrow and devious passages.

In 1832, the Boston Marine Society petitioned Congress for $3,000 for the placement of an unlighted stone beacon at Deer Island Point, at the north side of the entrance to Boston's inner harbor and about 500 yards south of the island's southeasterly point. This marker served as a navigational aid for almost 60 years.

In the annual reports for 1884 and 1885, the Lighthouse Board stated the following:

The steamers plying between Boston and the northern ports make use of the Broad Sound channels, and a light and fog-signal at this point are particularly desirable, because of the narrow and devious passages.

Congress appropriated $35,000 for the lighthouse on August 4, 1886. During the design process, it was realized that the initial appropriation was not sufficient, and an additional $6,000 was obtained.

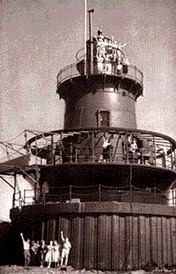

From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

A cylindrical caisson base for the lighthouse, 33 feet in diameter and 30 feet high, was sunk four feet into the gravel and clay of the spit, in about six feet of water.

The caisson was filled with concrete, with some space being left for a basement and cisterns.

The cast-iron superstructure built on top of the caisson had four levels between the lantern and basement, including living quarters. The lighthouse was painted brown except for the lantern, which was painted black.

The new light went into service on January 26, 1890, with a fixed white light interrupted by a red flash every 30 seconds, 57 feet above mean high water. The lens revolved by means of a clockwork mechanism that had to be periodically wound by hand.

A fog bell was mounted on the lower gallery deck, with striking machinery that produced a single blow every 10 seconds.

The caisson was filled with concrete, with some space being left for a basement and cisterns.

The cast-iron superstructure built on top of the caisson had four levels between the lantern and basement, including living quarters. The lighthouse was painted brown except for the lantern, which was painted black.

The new light went into service on January 26, 1890, with a fixed white light interrupted by a red flash every 30 seconds, 57 feet above mean high water. The lens revolved by means of a clockwork mechanism that had to be periodically wound by hand.

A fog bell was mounted on the lower gallery deck, with striking machinery that produced a single blow every 10 seconds.

|

The station was assigned a principal keeper and an assistant. Wesley A. Pingree (left) arrived as an assistant in 1893 and became principal keeper in 1895. His stay of six years was one of the longer stints in the station's history.

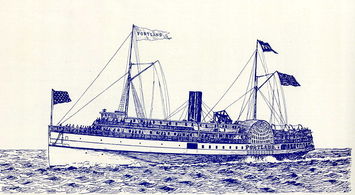

Pingree was keeper during the famous Portland Gale of November 1898. Many vessels were wrecked in the storm, including the steamer Portland, which was carrying nearly 200 people from Boston to Portland, Maine. |

Pingree later described his experience of the storm to historian Edward Rowe Snow:

The steamer Portland (Wikipedia Commons)

At two o'clock in the afternoon the ocean was as smooth as glass. At five p.m. it had started snowing and the wind was coming up. A little later the Bangor boat went by but returned to the harbor, as the sea was rapidly getting worse.

At 7 p.m. the Portland came down the channel, and the other boat, anchored in President Road, whistled a warning to her. At this time the waves were hitting so high that I was lashing my dory fast to the light.

Pingree rode out the storm inside the lighthouse, keeping watch all night. All told, 141 vessels were wrecked and 456 lives were lost in the Portland Gale, one of the worst storms in recorded New England history.

At 7 p.m. the Portland came down the channel, and the other boat, anchored in President Road, whistled a warning to her. At this time the waves were hitting so high that I was lashing my dory fast to the light.

Pingree rode out the storm inside the lighthouse, keeping watch all night. All told, 141 vessels were wrecked and 456 lives were lost in the Portland Gale, one of the worst storms in recorded New England history.

Joseph McCabe arrived as assistant keeper in June 1908. He made the pages of the Boston Globe in March 1913, when he purchased a piano and had it delivered to the lighthouse to "break the monotony of the lonely life in the isolated tower." Less than three years later, McCabe, who rented a room in East Boston when he wasn't at the lighthouse, became engaged to Gertrude Walter, a resident of that community. The couple planned a wedding on Easter Sunday, but it wasn't to be.

On Saturday, February 19, 1916, McCabe left the lighthouse to meet his fiancée on Deer Island, where they wrote out wedding invitations together. When he was ready to return, McCabe found that ice around the island had trapped his boat.

He decided to borrow a pair of rubber boots and walk across the spit to the lighthouse. He was followed by his friend, Wesley Pingree, who was by then an employee of the pumping station on Deer Island, and Pingree's 15-year-old son, Philip. As he jumped forward to make it past a gap in the spit, McCabe lost his footing and disappeared into the turbulent waters of the harbor. Employees from Deer Island rushed to the scene in a dory, but it was too late. The body of Joseph McCabe, who was 28 years old, was never recovered.

Judson Small, one of three lighthouse keeping brothers, was one of the keepers at Deer Island Light in the 1920s, through at least 1930. A 1930 clipping in the Boston Globe reported that Small and another keeper, Mal King, unable to reach the mainland due to rough weather, enjoyed "Cape Cod turkey" at the lighthouse for Thanksgiving. Cape Cod turkey was a euphemism for salt cod.

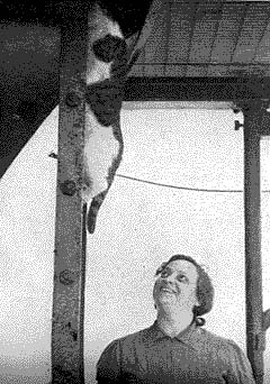

Left: The climbing cat of Deer Island Light. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

A short time later, in February 1931, Judson Small was marooned at the lighthouse by himself for a few days when King was unable to return due to bad weather. Small stayed awake for three consecutive nights during the ordeal.

Judson Small, one of three lighthouse keeping brothers, was one of the keepers at Deer Island Light in the 1920s, through at least 1930. A 1930 clipping in the Boston Globe reported that Small and another keeper, Mal King, unable to reach the mainland due to rough weather, enjoyed "Cape Cod turkey" at the lighthouse for Thanksgiving. Cape Cod turkey was a euphemism for salt cod.

Left: The climbing cat of Deer Island Light. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

A short time later, in February 1931, Judson Small was marooned at the lighthouse by himself for a few days when King was unable to return due to bad weather. Small stayed awake for three consecutive nights during the ordeal.

Judson's brother, Tom Small, who was keeper at the Narrows Light when it burned down in 1929, became the keeper in 1931.

While he was keeper, Tom Small had a pet that gained fame as "the climbing cat of Deer Island Light." Edward Rowe Snow reported that Small's cat would leap into the water, emerge with a fish in its mouth, climb the ladder, and eat the fish.

The caisson base of the lighthouse was battered repeatedly in storms. It was patched and banded for reinforcement around 1902, but by 1937 it was in such rough shape that a circular protective wall was built around the lower part of the structure.

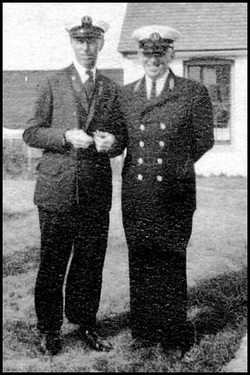

Right: Keeper Fred Bohm (L) of Deer Island Light visiting with Keeper Maurice Babcock at Boston Light on September 14, 1941. Courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

Fred Bohm became the last civilian keeper in the 1940s after leaving the Spectacle Island Range Lights, about two miles to the southwest in the harbor.

During the first year and a half of World War II, Keeper Bohm not only had to tend the light, but was also was required to patrol the area and watch for German submarines. After Bohm left, Coast Guard crews looked after the lighthouse.

In spite of the protective wall around the base, the lighthouse continued to deteriorate. The roof over the lower gallery had to be removed in 1965. The keepers did their best with makeshift repairs, but the lighthouse's days as a staffed station were numbered by the early 1970s.

The caisson base of the lighthouse was battered repeatedly in storms. It was patched and banded for reinforcement around 1902, but by 1937 it was in such rough shape that a circular protective wall was built around the lower part of the structure.

Right: Keeper Fred Bohm (L) of Deer Island Light visiting with Keeper Maurice Babcock at Boston Light on September 14, 1941. Courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

Fred Bohm became the last civilian keeper in the 1940s after leaving the Spectacle Island Range Lights, about two miles to the southwest in the harbor.

During the first year and a half of World War II, Keeper Bohm not only had to tend the light, but was also was required to patrol the area and watch for German submarines. After Bohm left, Coast Guard crews looked after the lighthouse.

In spite of the protective wall around the base, the lighthouse continued to deteriorate. The roof over the lower gallery had to be removed in 1965. The keepers did their best with makeshift repairs, but the lighthouse's days as a staffed station were numbered by the early 1970s.

According to the last Coast Guard keeper, Pedro Marticio, Deer Island Light was abandoned on February 19, 1972, at 1830 (6:30 p.m.).

Courtesy of Pedro Marticio

He later recalled:

At the time the press was calling it the worst nor'easter in 40 years. We had lost all power at 1000 and flooded out the engine room, when a wave broke in the plate glass windows and frames and washed down into the engine room. There were three of us on board during the storm, the CGC Pendant was dispatched to shoot us a line and pass us a pump.

When BMC John Butler, Officer in Charge of the Pendant, saw the tower starting to tip he informed Boston, and in turn they told me to abandon station. The Pendant rammed its bow into the tower and my crew and I jumped on board. When he backed into deep water he got broadsided by a wave that almost capsized the 65-foot tug. The storm was knocking three-story houses off their foundations on Winthrop Shore Drive.

At the time the press was calling it the worst nor'easter in 40 years. We had lost all power at 1000 and flooded out the engine room, when a wave broke in the plate glass windows and frames and washed down into the engine room. There were three of us on board during the storm, the CGC Pendant was dispatched to shoot us a line and pass us a pump.

When BMC John Butler, Officer in Charge of the Pendant, saw the tower starting to tip he informed Boston, and in turn they told me to abandon station. The Pendant rammed its bow into the tower and my crew and I jumped on board. When he backed into deep water he got broadsided by a wave that almost capsized the 65-foot tug. The storm was knocking three-story houses off their foundations on Winthrop Shore Drive.

It was apparent that the lighthouse had deteriorated to the point that it was unsafe.

Courtesy of Pedro Marticio

The Coast Guard estimated that repair and restoration would cost up to $400,000. The Massachusetts Historic Commission decided that the lighthouse was not eligible for the National Register, so the way was cleared to destroy the old lighthouse.

Beginning on June 14, 1982, the old lighthouse was removed. The change took about six weeks in all. During this period a lighted buoy served as a temporary aid to navigation. The familiar old landmark was replaced by a white fiberglass tower, set on the original foundation.

The tower was believed to be the first fiberglass light in the country. It was built in England and was designed to withstand winds of 110 mph. The new light cost $100,000.

Beginning on June 14, 1982, the old lighthouse was removed. The change took about six weeks in all. During this period a lighted buoy served as a temporary aid to navigation. The familiar old landmark was replaced by a white fiberglass tower, set on the original foundation.

The tower was believed to be the first fiberglass light in the country. It was built in England and was designed to withstand winds of 110 mph. The new light cost $100,000.

There were complaints that the white tower blended in with the background of Deer Island.

Meanwhile, in March of 1983, Great Point Lighthouse on Nantucket was destroyed in a storm. The Coast Guard decided to replace it with a fiberglass tower, so they moved the Deer Island tower to Nantucket. The fiberglass tower was never actually put into use on Nantucket; a wooden structure was used instead.

Right: The white tower erected in 1982, U.S. Coast Guard photo.

A 33-foot brown fiberglass tower replaced the white one at Deer Island Light. The temporary tower at Great Point was later replaced by a $1 million replica of the original lighthouse, but there has been no such luck for Deer Island Light.

In late 2014, it was announced that the fiberglass tower and the foundation of the 1890 lighthouse would be removed, and a new pile-supported platform and light would be erected in their place. The new light structure was in service by late 2015.

The light can be seen from the public walking trail around the perimeter of Deer Island, accessible from the town of Winthrop.

Right: The white tower erected in 1982, U.S. Coast Guard photo.

A 33-foot brown fiberglass tower replaced the white one at Deer Island Light. The temporary tower at Great Point was later replaced by a $1 million replica of the original lighthouse, but there has been no such luck for Deer Island Light.

In late 2014, it was announced that the fiberglass tower and the foundation of the 1890 lighthouse would be removed, and a new pile-supported platform and light would be erected in their place. The new light structure was in service by late 2015.

The light can be seen from the public walking trail around the perimeter of Deer Island, accessible from the town of Winthrop.

Film of Deer Island Light taken by historian Edward Rowe Snow, circa 1960s (courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell).

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Farley (1890); Michael J. Curran (assistant 1890); Ethan Allen (1890-1891); Everett F. Boyd (assistant 1890-1891, head keeper 1891-1892); Nathaniel F. Hooper (assistant 1891); Samuel Liscom (assistant 1891-1892, head keeper 1892-1893) Herbert N. Ranlett (assistant 1892); Alfred Williams (assistant 1892 and 1895); Wesley A. Pingree (assistant 1893-1894, head keeper 1895-1899); William Jamieson (assistant 1896-1899); Frank E. Lowe (assistant 1899-1900); George W. Jaques (1899); Michael Campbell (1899-1900); Howard Parker (1900-1906); George W. Bailey (assistant, 1900-1901); William C. Daggett (assistant, 1901); Reuben D. Weatherbee (assistant, 1901-1902); Frederick W. Freeman (assistant 1902-1905); Murdock Ross Trevoy (assistant 1905-1906); Charles Jordon (1906-1911?); George M. Reamy (assistant, 1906-1907); Charles B. Hill (assistant, 1907); Robert J. Sweeney (assistant 1907-1908); W. F. Morris (assistant 1908-?); George B. Bassett (assistant, ?-1914); Joseph McCabe (assistant 1908-1916, died in service); Elliott C. Hadley (1919-1922); Mal (Malcolm?) King (c. 1930); Judson Small (c. 1920s to at least 1930); Tom Small (1931 to at least 1940); Edmond Louis Arruda (c. early 1940s); Fred Bohm (c. 1940s); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1952); Tony Ashdon (Coast Guard, c. 1963-1966); John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Bob Rodgers (Coast Guard, 1970); Pedro Marticio (Coast Guard, ?-1972)

John Farley (1890); Michael J. Curran (assistant 1890); Ethan Allen (1890-1891); Everett F. Boyd (assistant 1890-1891, head keeper 1891-1892); Nathaniel F. Hooper (assistant 1891); Samuel Liscom (assistant 1891-1892, head keeper 1892-1893) Herbert N. Ranlett (assistant 1892); Alfred Williams (assistant 1892 and 1895); Wesley A. Pingree (assistant 1893-1894, head keeper 1895-1899); William Jamieson (assistant 1896-1899); Frank E. Lowe (assistant 1899-1900); George W. Jaques (1899); Michael Campbell (1899-1900); Howard Parker (1900-1906); George W. Bailey (assistant, 1900-1901); William C. Daggett (assistant, 1901); Reuben D. Weatherbee (assistant, 1901-1902); Frederick W. Freeman (assistant 1902-1905); Murdock Ross Trevoy (assistant 1905-1906); Charles Jordon (1906-1911?); George M. Reamy (assistant, 1906-1907); Charles B. Hill (assistant, 1907); Robert J. Sweeney (assistant 1907-1908); W. F. Morris (assistant 1908-?); George B. Bassett (assistant, ?-1914); Joseph McCabe (assistant 1908-1916, died in service); Elliott C. Hadley (1919-1922); Mal (Malcolm?) King (c. 1930); Judson Small (c. 1920s to at least 1930); Tom Small (1931 to at least 1940); Edmond Louis Arruda (c. early 1940s); Fred Bohm (c. 1940s); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1952); Tony Ashdon (Coast Guard, c. 1963-1966); John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Bob Rodgers (Coast Guard, 1970); Pedro Marticio (Coast Guard, ?-1972)