History of Beavertail Lighthouse, Jamestown, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

The lighthouse established in 1749 at Beavertail Point, at the southern tip of Conanicut Island, was the granddaddy of all Rhode Island lighthouses and only the third one—after Boston Harbor and Nantucket’s Brant Point—in the American colonies.

U.S. Coast Guard

Today, the light station remains a prime spot for soaking in the spectacular vistas at the mouth of Narragansett Bay and is among the most popular historic destinations in the state.

Conanicut Island, about 6,000 acres, was a favorite summer home for Conanicus (or Quonanicus), a sachem of the Narragansett Indians. English settlers were first given permission to pasture sheep on the island in 1638, and a group of about 100 buyers obtained title to the land in 1657, in exchange for 100 pounds paid in wampum.

The island was divided into about a dozen large plots, and much land at the southern part went to Benedict Arnold, great-grandfather of the famous general and traitor of the American Revolution.

Conanicut Island, about 6,000 acres, was a favorite summer home for Conanicus (or Quonanicus), a sachem of the Narragansett Indians. English settlers were first given permission to pasture sheep on the island in 1638, and a group of about 100 buyers obtained title to the land in 1657, in exchange for 100 pounds paid in wampum.

The island was divided into about a dozen large plots, and much land at the southern part went to Benedict Arnold, great-grandfather of the famous general and traitor of the American Revolution.

Beavertail Point got its name because the southern peninsula of the island resembles a beaver in shape, with the head at its northern end and the tail at the southern end.

U.S. Coast Guard

The strategic importance of Beavertail, which marks the entrances to both the east and west passages of Narragansett Bay, was obvious to the early settlers, as well as to merchants who were concerned about the safety of their vessels. A watch house was erected at Beavertail sometime prior to 1705, and a lighted beacon was erected in 1712. Local Indians tended the beacon.

In 1719, a “great gun” at Beavertail was provided by the General Court of Rhode Island to “answer ships in a fog”—in other words, to serve as a primitive fog signal.

With foreign trade blossoming from Newport, a number of local merchants petitioned for a true lighthouse in 1730. A lighthouse was authorized by the colony in 1738, but war with Spain delayed the project until 1749, when a wooden lighthouse was erected. To pay the costs of maintaining the lighthouse, a tax was levied on all vessels entering the nearby harbors.

In 1719, a “great gun” at Beavertail was provided by the General Court of Rhode Island to “answer ships in a fog”—in other words, to serve as a primitive fog signal.

With foreign trade blossoming from Newport, a number of local merchants petitioned for a true lighthouse in 1730. A lighthouse was authorized by the colony in 1738, but war with Spain delayed the project until 1749, when a wooden lighthouse was erected. To pay the costs of maintaining the lighthouse, a tax was levied on all vessels entering the nearby harbors.

The first keeper was local resident Abel Franklin, who had been a member of the committee appointed to build the lighthouse.

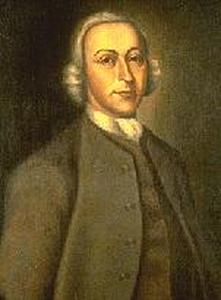

Peter Harrison

(Wikipedia Commons)

The 1749 tower was 24 feet in diameter at its base, 13 feet at the top. Its total height was 69 feet, including an 11-foot-high lantern, 8 feet in diameter. The lighthouse’s lamps were fueled by whale oil. The designer was Peter Harrison, a former sea captain sometimes referred to as America’s first architect. Harrison also designed Newport’s Touro Synagogue (America’s first synagogue), Redwood Library, and Brick Market, as well as King’s Chapel in Boston.

The first lighthouse was destroyed by fire on July 22, 1753, and it was reported that Franklin subsequently kept an ordinary lantern burning for the benefit of shipping.

In August 1753, a committee was appointed for the purpose of “erecting another Lighthouse with stone or brick, at the Place where that lately burnt stood, as soon as they can conveniently.”

It was recommended that building materials from Fort George on Goat Island be used in the construction. The new tower was built on the same spot as the first one. The committee determined that two additional acres of land were needed for the proper building of a new lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling.

The first lighthouse was destroyed by fire on July 22, 1753, and it was reported that Franklin subsequently kept an ordinary lantern burning for the benefit of shipping.

In August 1753, a committee was appointed for the purpose of “erecting another Lighthouse with stone or brick, at the Place where that lately burnt stood, as soon as they can conveniently.”

It was recommended that building materials from Fort George on Goat Island be used in the construction. The new tower was built on the same spot as the first one. The committee determined that two additional acres of land were needed for the proper building of a new lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling.

The lighthouse was soon rebuilt, designed again by Harrison.

Base of the original Beavertail Lighthouse

Not much is known about the light’s earliest keepers, but one anecdote

survives in a typescript at the Newport Historical Society called

Historical Story of Jamestown and early days around Narragansett Bay,

by Lena Hartwell Clarke and Elizabeth Clarke Helmick.

It seems his wife awakened the keeper during a terrible storm. “Husband, husband, wake up,” she cried. “The British or the Day of Judgment has come.” The keeper, a gruff old salt, grabbed his musket and replied, “Let ’em come. I am prepared for either of them!”

The British occupied Newport from December 1776 to October 1779. William Ellery, collector of the port of Newport and local lighthouse superintendent, later described what happened to Beavertail Lighthouse as the British evacuated the bay:

The British in the Revolutionary War set fire to it and the flames so shocked the walls; especially about the Windows, that, notwithstanding they are four feet and half thick at the bottom and a half feet thick at the top, our Masons have not since been able to make them tight and secure against the impressions of storms of rain.

The lighting apparatus from the lighthouse was taken by the British, but was later recovered. Some of the equipment was later used in other lighthouses, including those at Point Judith and Watch Hill in Rhode Island.

Beavertail Light Station was ceded to the federal government in 1793. Administration of lighthouses on the local level went to the collectors of customs. The customs collector for Newport, William Ellery, became Rhode Island’s first lighthouse superintendent.

William Martin was keeper from the 1780s until his death in 1803. Ellery described Martin as “well qualified,” and reported that the keeper diligently worked to keep the lantern’s glass panes free of salt spray. Ellery reported that the lantern was also plagued by seabirds that broke the glass with regularity.

Philip Caswell was the keeper at Beavertail when the hurricane of September 23, 1815, toppled the lighthouse several miles away at Point Judith. At Beavertail, the gale shattered 20 panes of glass in the lantern, and waves poured into the dwelling through the badly damaged roof. Caswell moved his wife to a nearby farmhouse, but he rode out the storm himself in the keeper’s house along with an invalid uncle. A larger keeper’s house was soon built.

In 1829, a 600-pound fog bell was installed at Beavertail, mounted on a 12-foot brick tower, and sounding 10 times each minute by means of a clockwork mechanism that had to be wound by the keeper. It was used only for about four years, as it was impossible to hear over the sound of the thundering surf.

In 1838, an inspection by Lieut. George M. Bache reported that Beavertail Light was 64 feet high and 98 feet above sea level, with the light visible for 15 3/4 nautical miles. Bache described the lighting apparatus:

The lanterns contain fifteen lamps, with reflectors, arranged around two circular copper tables, each three feet in diameter. The lower table supports eight lamps, which illuminate every point of the horizon; on the upper table there are seven lamps, the vacant space being towards the land... Several of the reflectors are bent from their original forms, which is probably owing to their great lightness, their diameters being 9 inches, and weight from 7 ounces to 1 pound; two of them being very much worn and cracked. The light-keeper informed me that they had been furnished by the contractors on their last annual visit.

Winslow Lewis fit the lantern with new lighting apparatus three years later.

Robert H. Weeden became keeper in 1844. He died just four years later and was replaced by his widow, Demaris Weeden. The local superintendent, Edward W. Lawton, described Demaris Weeden as a “respectable well disposed woman of good habits,” and an 1850 inspection described the lighting apparatus as “in good order and clean.” The same inspection, however, reported that the tower was badly in need of repointing and the lantern was described as very rusty. Demaris Weeden’s teenaged son helped with the lighthouse work.

Beavertail has probably seen more types of fog signals than any other New England lighthouse station, starting with the 1719 cannon and the short-lived 1829 bell. In 1851, a fog whistle was installed, operated by compressed air. Celadon Daboll, an inventor from New London, Connecticut, developed the system. A horse, driving a wheel 10 feet in diameter, powered the compressor.

An 1851 report read:

Fog seldom lasts all day. It will require about one-third of the time (during fogs) to work the horse, to keep up a regular series of signals. Keeper [Demaris Weeden’s son] makes fog signals when he wakes up and finds a fog. No means to ascertain if it is foggy; generally gets up at 1 a.m. to trim lamps.

It seems his wife awakened the keeper during a terrible storm. “Husband, husband, wake up,” she cried. “The British or the Day of Judgment has come.” The keeper, a gruff old salt, grabbed his musket and replied, “Let ’em come. I am prepared for either of them!”

The British occupied Newport from December 1776 to October 1779. William Ellery, collector of the port of Newport and local lighthouse superintendent, later described what happened to Beavertail Lighthouse as the British evacuated the bay:

The British in the Revolutionary War set fire to it and the flames so shocked the walls; especially about the Windows, that, notwithstanding they are four feet and half thick at the bottom and a half feet thick at the top, our Masons have not since been able to make them tight and secure against the impressions of storms of rain.

The lighting apparatus from the lighthouse was taken by the British, but was later recovered. Some of the equipment was later used in other lighthouses, including those at Point Judith and Watch Hill in Rhode Island.

Beavertail Light Station was ceded to the federal government in 1793. Administration of lighthouses on the local level went to the collectors of customs. The customs collector for Newport, William Ellery, became Rhode Island’s first lighthouse superintendent.

William Martin was keeper from the 1780s until his death in 1803. Ellery described Martin as “well qualified,” and reported that the keeper diligently worked to keep the lantern’s glass panes free of salt spray. Ellery reported that the lantern was also plagued by seabirds that broke the glass with regularity.

Philip Caswell was the keeper at Beavertail when the hurricane of September 23, 1815, toppled the lighthouse several miles away at Point Judith. At Beavertail, the gale shattered 20 panes of glass in the lantern, and waves poured into the dwelling through the badly damaged roof. Caswell moved his wife to a nearby farmhouse, but he rode out the storm himself in the keeper’s house along with an invalid uncle. A larger keeper’s house was soon built.

In 1829, a 600-pound fog bell was installed at Beavertail, mounted on a 12-foot brick tower, and sounding 10 times each minute by means of a clockwork mechanism that had to be wound by the keeper. It was used only for about four years, as it was impossible to hear over the sound of the thundering surf.

In 1838, an inspection by Lieut. George M. Bache reported that Beavertail Light was 64 feet high and 98 feet above sea level, with the light visible for 15 3/4 nautical miles. Bache described the lighting apparatus:

The lanterns contain fifteen lamps, with reflectors, arranged around two circular copper tables, each three feet in diameter. The lower table supports eight lamps, which illuminate every point of the horizon; on the upper table there are seven lamps, the vacant space being towards the land... Several of the reflectors are bent from their original forms, which is probably owing to their great lightness, their diameters being 9 inches, and weight from 7 ounces to 1 pound; two of them being very much worn and cracked. The light-keeper informed me that they had been furnished by the contractors on their last annual visit.

Winslow Lewis fit the lantern with new lighting apparatus three years later.

Robert H. Weeden became keeper in 1844. He died just four years later and was replaced by his widow, Demaris Weeden. The local superintendent, Edward W. Lawton, described Demaris Weeden as a “respectable well disposed woman of good habits,” and an 1850 inspection described the lighting apparatus as “in good order and clean.” The same inspection, however, reported that the tower was badly in need of repointing and the lantern was described as very rusty. Demaris Weeden’s teenaged son helped with the lighthouse work.

Beavertail has probably seen more types of fog signals than any other New England lighthouse station, starting with the 1719 cannon and the short-lived 1829 bell. In 1851, a fog whistle was installed, operated by compressed air. Celadon Daboll, an inventor from New London, Connecticut, developed the system. A horse, driving a wheel 10 feet in diameter, powered the compressor.

An 1851 report read:

Fog seldom lasts all day. It will require about one-third of the time (during fogs) to work the horse, to keep up a regular series of signals. Keeper [Demaris Weeden’s son] makes fog signals when he wakes up and finds a fog. No means to ascertain if it is foggy; generally gets up at 1 a.m. to trim lamps.

Word was received that the new signal could be heard clearly at locations at least six miles away.

John Ericsson (Wikipedia Commons)

Edward Lawton, the local lighthouse

superintendent, was awakened by the signal at his Newport home. At

Newport’s Fort Adams, an officer mistook the sound for the whistle of

the mail steamer. The use of a horse to power the signal proved

impractical, however, and the system was used for only about two years.

A new steam whistle, first in the nation, was installed in 1857, then a fog signal driven by a hot air engine in 1868. The hot air engine was designed by John Ericsson, the builder of the famous iron-clad vessel Monitor. A new compressed air siren went into use in 1900, replaced by diaphragm horns and finally by today's electronic fog signals.

An 1851 report showed Beavertail Lighthouse to be the "worst built tower yet seen." $14,500 was appropriated in 1854 for a new lighthouse, illuminating apparatus and fog signal.

A new steam whistle, first in the nation, was installed in 1857, then a fog signal driven by a hot air engine in 1868. The hot air engine was designed by John Ericsson, the builder of the famous iron-clad vessel Monitor. A new compressed air siren went into use in 1900, replaced by diaphragm horns and finally by today's electronic fog signals.

An 1851 report showed Beavertail Lighthouse to be the "worst built tower yet seen." $14,500 was appropriated in 1854 for a new lighthouse, illuminating apparatus and fog signal.

The new tower was built in 1856, and the 45-foot square granite lighthouse still stands.

Silas Gardner Shaw and his wife Ann, c. 1858. Courtesy of Cheryl Vislay.

The lantern originally held a third-order Fresnel lens. A new large brick keeper's house was built a short time later.

Demaris Weeden was still keeper when the new lighthouse went into service; she remained until the following year. After a brief stint by Joshua Rathbun, Silas Gardner Shaw became keeper.

Shaw stayed for four years and later returned for six more years in the 1860s. His daughter, Lena Clarke of Jamestown, recounted some memories in a letter many years later:

When we first went there was just a light, a barn and a stone wall around the government property. We soon had a henhouse, a sty (kept white), a flower garden, trellis with climbing roses, and a large vegetable garden. . . I often heard my father tell about a vessel going on the rocks south of the light and how the men came ashore carrying pails of cider and rolling pins, part of the cargo. . . In a severe storm, when another craft was grounded, one of the crew made his way ashore, carrying a heavy sea chest on his back, and the wind was so strong it blew him down on the rocks. . . Whenever my father heard a noise in the night, he always took his gaff hook and lantern and went along the shore to try to find out what it was. One night he saved five or six men whose yawl had washed on the rocks, and brought them to the light to remain during the night.

Peter Lee was keeper between Shaw’s two stints. With his wife and six children, Lee arrived at Beavertail in a sailboat with a horse in the bow and supplies in the stern. Lee’s daughter, Ella, later recalled happy times at Beavertail and said the children all pitched in by cleaning, sweeping, helping with the garden and animals, and assisting their mother in the kitchen.

William W. Wales, a native of Middletown, Rhode Island, who had previously been keeper of Dutch Island Light for 8 years, began a 22-year stay as keeper in 1873. Wales and his family were renowned for the excellent clambakes they held at the light station. Two of the keeper’s sons, John and George, served as assistant keepers. In June 1895, when the 76-year-old Keeper Wales died, the Newport Daily News reported:

Captain Wales will be missed by a large circle of friends, as he had an extensive acquaintance, Beavertail Light having been visited by thousands of people during his time as light keeper, many of whom have had the occasion to speak in praise of his hospitality. The flag of the Beavertail Fishing Club and several others on the island are at half mast in his honor.

In 1899, a smaller fourth-order lens that rotated on a bed of mercury replaced the third-order lens. The lens showed a group of eight flashes, separated by two seconds, followed by 15 seconds of darkness. During the following year, a new second-class fog siren was installed. Just five years later, a new first-class siren was installed along with new engines and air compressors.

The year 1900 saw another significant change. The tower, which had been unpainted until then, was painted white on its upper half. That color scheme was abandoned many years ago.

One of the most colorful personalities in the history of Beavertail Light was George T. Manders (1870-1954), a navy veteran who was an assistant keeper from 1913 to 1919 and then head keeper until 1937. The fuel for the light had switched to kerosene in the 1880s, and Manders was there for the change to electricity in May 1931. Later that year, a reporter named Thomas A. Langan wrote a profile of Keeper Manders for the Providence Evening Bulletin:

In the warmth and security of his living room, in a house attached to the lighthouse tower, Keeper Manders sits and smokes and talks of “the light.” He is patently proud of it. It is his job and also his hobby. He cites the fact that summer visitors from every State in the Union stop and “go through the light.”“We have an off-shore wind tonight,” Mr. Manders observed. “There won’t be any heavy weather.”

“When a sou’easter screeches through here you see some weather,” Mr. Manders declared. “I remember the night a few years ago when a sou’easter came through and raised plenty of trouble. I went out to set the fog signal running and the wind threw me right across the yard, into a wall. I crept over to the whistle house on my hands and knees.”

Demaris Weeden was still keeper when the new lighthouse went into service; she remained until the following year. After a brief stint by Joshua Rathbun, Silas Gardner Shaw became keeper.

Shaw stayed for four years and later returned for six more years in the 1860s. His daughter, Lena Clarke of Jamestown, recounted some memories in a letter many years later:

When we first went there was just a light, a barn and a stone wall around the government property. We soon had a henhouse, a sty (kept white), a flower garden, trellis with climbing roses, and a large vegetable garden. . . I often heard my father tell about a vessel going on the rocks south of the light and how the men came ashore carrying pails of cider and rolling pins, part of the cargo. . . In a severe storm, when another craft was grounded, one of the crew made his way ashore, carrying a heavy sea chest on his back, and the wind was so strong it blew him down on the rocks. . . Whenever my father heard a noise in the night, he always took his gaff hook and lantern and went along the shore to try to find out what it was. One night he saved five or six men whose yawl had washed on the rocks, and brought them to the light to remain during the night.

Peter Lee was keeper between Shaw’s two stints. With his wife and six children, Lee arrived at Beavertail in a sailboat with a horse in the bow and supplies in the stern. Lee’s daughter, Ella, later recalled happy times at Beavertail and said the children all pitched in by cleaning, sweeping, helping with the garden and animals, and assisting their mother in the kitchen.

William W. Wales, a native of Middletown, Rhode Island, who had previously been keeper of Dutch Island Light for 8 years, began a 22-year stay as keeper in 1873. Wales and his family were renowned for the excellent clambakes they held at the light station. Two of the keeper’s sons, John and George, served as assistant keepers. In June 1895, when the 76-year-old Keeper Wales died, the Newport Daily News reported:

Captain Wales will be missed by a large circle of friends, as he had an extensive acquaintance, Beavertail Light having been visited by thousands of people during his time as light keeper, many of whom have had the occasion to speak in praise of his hospitality. The flag of the Beavertail Fishing Club and several others on the island are at half mast in his honor.

In 1899, a smaller fourth-order lens that rotated on a bed of mercury replaced the third-order lens. The lens showed a group of eight flashes, separated by two seconds, followed by 15 seconds of darkness. During the following year, a new second-class fog siren was installed. Just five years later, a new first-class siren was installed along with new engines and air compressors.

The year 1900 saw another significant change. The tower, which had been unpainted until then, was painted white on its upper half. That color scheme was abandoned many years ago.

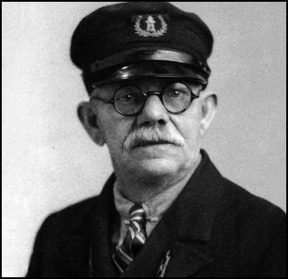

One of the most colorful personalities in the history of Beavertail Light was George T. Manders (1870-1954), a navy veteran who was an assistant keeper from 1913 to 1919 and then head keeper until 1937. The fuel for the light had switched to kerosene in the 1880s, and Manders was there for the change to electricity in May 1931. Later that year, a reporter named Thomas A. Langan wrote a profile of Keeper Manders for the Providence Evening Bulletin:

In the warmth and security of his living room, in a house attached to the lighthouse tower, Keeper Manders sits and smokes and talks of “the light.” He is patently proud of it. It is his job and also his hobby. He cites the fact that summer visitors from every State in the Union stop and “go through the light.”“We have an off-shore wind tonight,” Mr. Manders observed. “There won’t be any heavy weather.”

“When a sou’easter screeches through here you see some weather,” Mr. Manders declared. “I remember the night a few years ago when a sou’easter came through and raised plenty of trouble. I went out to set the fog signal running and the wind threw me right across the yard, into a wall. I crept over to the whistle house on my hands and knees.”

Manders lived in the principal keeper’s house with his son, and they had a radio for entertainment—listening to the nightly news flashes was a ritual.

_A housekeeper named Mary Pollock kept things tidy. She had run a florist shop in Providence, and the plants she cultivated in the keeper’s house added a warm touch.

Manders had some unusual hobbies. Using a jackknife, he carved miniature baskets from peach stones, to be used as watch charms. Each one took about two hours to carve. “Makes the time go,” he explained.

Left: George T. Manders, courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association.

In a 1970 article, Richard L. Champlin said that Conanicut islanders remembered Manders as the keeper “who claimed he had seen a white whale; but, they add, the day that he saw that, it was so foggy you couldn’t see your fist in front of your face.” Champlin quoted a Jamestown resident: “George Manders could tell a story before it happened.”

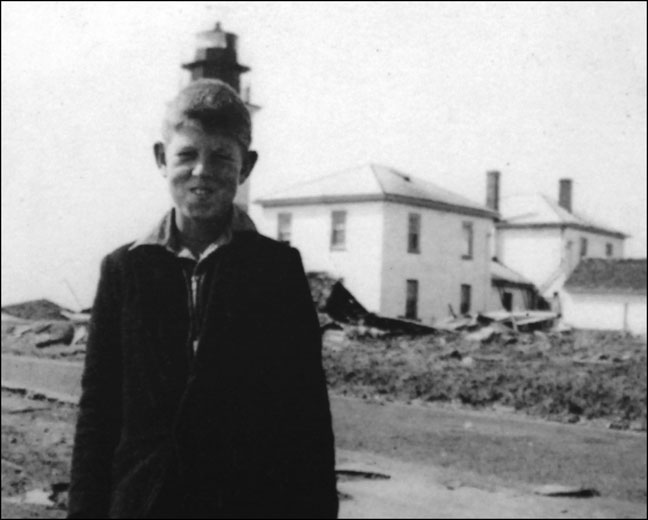

After Manders retired, Carl Chellis took over as keeper on January 1, 1938. Chellis would stay at Beavertail for a decade. He had the misfortune to be at the light station for the worst storm in recorded New England history, the hurricane of September 21, 1938.

The hurricane damaged most of the buildings at Beavertail, and also exposed the foundation of the original 1749 tower, 100 feet from the new tower.

Manders had some unusual hobbies. Using a jackknife, he carved miniature baskets from peach stones, to be used as watch charms. Each one took about two hours to carve. “Makes the time go,” he explained.

Left: George T. Manders, courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association.

In a 1970 article, Richard L. Champlin said that Conanicut islanders remembered Manders as the keeper “who claimed he had seen a white whale; but, they add, the day that he saw that, it was so foggy you couldn’t see your fist in front of your face.” Champlin quoted a Jamestown resident: “George Manders could tell a story before it happened.”

After Manders retired, Carl Chellis took over as keeper on January 1, 1938. Chellis would stay at Beavertail for a decade. He had the misfortune to be at the light station for the worst storm in recorded New England history, the hurricane of September 21, 1938.

The hurricane damaged most of the buildings at Beavertail, and also exposed the foundation of the original 1749 tower, 100 feet from the new tower.

Keeper Chellis survived the storm, but his seven-year-old daughter Marion was one of six children who died when they were swept away after their school bus was blocked by a car and they were forced to attempt to walk to safety.

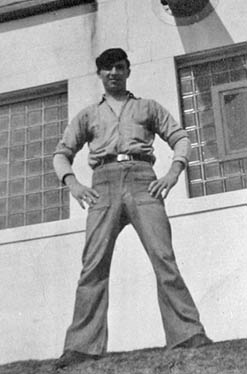

Edward A. Donahue

Chellis's son, Clayton, and the driver were the only survivors of those who had been on board the bus.

Meanwhile, Assistant Keeper Edward A. Donahue threw himself into the ocean to escape the engine room, which was collapsing around him, believing "it was the easiest way to die."

Donahue's son dove in to try to save his father, and both were eventually able to swim back to shore and find shelter. Edward Donahue remained at Beavertail until his death in1953, a veteran of over 40 years in the Lighthouse Service and Coast Guard.

Meanwhile, Assistant Keeper Edward A. Donahue threw himself into the ocean to escape the engine room, which was collapsing around him, believing "it was the easiest way to die."

Donahue's son dove in to try to save his father, and both were eventually able to swim back to shore and find shelter. Edward Donahue remained at Beavertail until his death in1953, a veteran of over 40 years in the Lighthouse Service and Coast Guard.

|

Right: Varoujan Karentz of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association speaks about the area around Beavertail (at the southern end of Jamestown, Rhode Island) during World War II. |

|

During World War II, the lighthouse shared Beavertail with Fort Burnside, a Harbor Entrance Control Point monitoring the movement of ships in and out of Narragansett Bay.

In 1954, when a powerful hurricane struck the coast, a chimney

collapsed in the kitchen of the keeper's house, blocking an entryway

to the other house. Coast Guard keeper Dom Turillo helped

his children through the window and they escaped to the other

house, where they survived the storm unscathed.

Turillo and his wife, Dorothy, raised 11 children at Beavertail, where they remained until 1970 (with a break in the middle, when Turillo worked at sea). Years later, their daughter, Linda Levesque, recalled life at the lighthouse. She and her older brother often helped wind up the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens, and they raised and lowered the flag every day.

Other memories included white-glove inspections of the station by Coast Guard officers—the children would sit on the sofa and watch. The Coast Guard keepers kept the premises so clean that “could have eaten off the engine room floor,” according to Levesque. She also remembered her father securing himself with a rope and swimming out to rescue boaters who had become trapped in the rocks.

Left: Coast Guard keeper Dominic Turillo. Courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association.

Turillo and his wife, Dorothy, raised 11 children at Beavertail, where they remained until 1970 (with a break in the middle, when Turillo worked at sea). Years later, their daughter, Linda Levesque, recalled life at the lighthouse. She and her older brother often helped wind up the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens, and they raised and lowered the flag every day.

Other memories included white-glove inspections of the station by Coast Guard officers—the children would sit on the sofa and watch. The Coast Guard keepers kept the premises so clean that “could have eaten off the engine room floor,” according to Levesque. She also remembered her father securing himself with a rope and swimming out to rescue boaters who had become trapped in the rocks.

Left: Coast Guard keeper Dominic Turillo. Courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association.

After its automation in 1972, Beavertail Light ran into recurring problems with vandalism.

The light was shot out by gunfire in 1975 and remained dark for several days before it could be repaired. It cost about $1,700 to fix the beacon and broken windows. Capt. R. J. Hanson, commander of U.S. Coast Guard Group Woods Hole, Massachusetts, commented, "I'd like to have some of these vandals out there on the bridge of an inbound tanker some night and let them see what it's like."

The fourth-order Fresnel lens, which had replaced the original lens, was removed and replaced by a modern optic.

Beavertail Light is located within Beavertail State Park and is easily accessible by car. The light itself remains an active aid to navigation and is maintained by the Coast Guard.

The assistant keeper's house, built in 1898, was leased to the Rhode Island Parks Association in the late 1980s and has been converted into the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum. A fourth-order Fresnel lens is on display along with exhibits on Rhode Island's lighthouses, and there is also a small gift shop.

The lighthouse tower deteriorated over the years. After being awarded a grant award of $227,000 from the Champlin Foundations and a $100,000 matching grant from the RI Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, the BLMA hired the Abcore Restoration Company, Inc. of Narragansett, RI, to carry out restoration work. The project was completed in October 2009. The exterior stonework was repointed, and the lantern and interior were fully restored. At the same time, significant repairs were carried out on the two dwellings. Click here for details of the restoration.

In early 2013, the BLMA announced that the van Beuren Charitable Foundation of Newport had awarded the organization a $112,000 grant for improved handicapped accessibility and the installation of a new mini theater and interactive computer exhibits in the museum. In addition, it was announced that the museum would be expanded 1150 feet into the first floor of the keeper's house. The expansion was completed in 2014.

The fourth-order Fresnel lens, which had replaced the original lens, was removed and replaced by a modern optic.

Beavertail Light is located within Beavertail State Park and is easily accessible by car. The light itself remains an active aid to navigation and is maintained by the Coast Guard.

The assistant keeper's house, built in 1898, was leased to the Rhode Island Parks Association in the late 1980s and has been converted into the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum. A fourth-order Fresnel lens is on display along with exhibits on Rhode Island's lighthouses, and there is also a small gift shop.

The lighthouse tower deteriorated over the years. After being awarded a grant award of $227,000 from the Champlin Foundations and a $100,000 matching grant from the RI Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, the BLMA hired the Abcore Restoration Company, Inc. of Narragansett, RI, to carry out restoration work. The project was completed in October 2009. The exterior stonework was repointed, and the lantern and interior were fully restored. At the same time, significant repairs were carried out on the two dwellings. Click here for details of the restoration.

In early 2013, the BLMA announced that the van Beuren Charitable Foundation of Newport had awarded the organization a $112,000 grant for improved handicapped accessibility and the installation of a new mini theater and interactive computer exhibits in the museum. In addition, it was announced that the museum would be expanded 1150 feet into the first floor of the keeper's house. The expansion was completed in 2014.

For more information, or to become a member of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association and receive their newsletter, contact:

Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association

P.O. Box 83, Jamestown, RI 02835

Left: A view from the top of the tower with Point Judith in the distance.

P.O. Box 83, Jamestown, RI 02835

Left: A view from the top of the tower with Point Judith in the distance.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Abel Franklin (1749-?); Jerathmeel Bowers (1770), Josiah Arnold (1770-?); William Martin (c. 1783-1803); Philip Caswell (1803-1816); George Shearman (1816-1829); Sylvester Hazard (1829-1844); Robert H. Weeden (1844-1848); Demaris Weeden (1848-1857); Joshua B. Rathbun (1857-1858); Henry Rathbun (assistant, 1857); Silas Gardner Shaw (1858-1862 and 1863-1869); E. E. Taylor (assistant, 1859); William Spooner (assistant, 1859); William H. Carr (1859-1862); Benjamin W. Walker (assistant, c. 1862); William D. Weeden (1862); Albert Caswell (assistant, 1862); Peter Lee (1862-1863); Christopher Austen (assistant, 1863); William Batchelder (assistant, 1863-1864); Ann N. Shaw (assistant, 1864-1869); Thomas King (1869-1873?); Andrew King (assistant, 1869); W. W. Wales (1873-1895); Charles H. Lake (assistant 1875); George A. Brown (assistant, 1875-1885); John S. Wales (assistant 1885-1888); George B. Wales (assistant 1888-1895, head keeper 1895-1913?); George T. Manders (assistant 1913-1919; principal keeper 1919-1937); Stanley Roode (assistant, 1919-1920); Carl Chellis (1938-1945); Edward A. Donahue (assistant 1920-1947, principal keeper 1948-1953); Ronald Bugenske (Coast Guard assistant 1962–1965); Calvin Hirsch (Coast Guard assistant 1965–1969); Dominic Turillo (Coast Guard assistant 1951-1953, then officer in charge, 1954-1969); John K. Martin (Coast Guard, 1969); George Light (Coast Guard 1969-1972); John Baxter (Coast Guard, 1970-1972)

Abel Franklin (1749-?); Jerathmeel Bowers (1770), Josiah Arnold (1770-?); William Martin (c. 1783-1803); Philip Caswell (1803-1816); George Shearman (1816-1829); Sylvester Hazard (1829-1844); Robert H. Weeden (1844-1848); Demaris Weeden (1848-1857); Joshua B. Rathbun (1857-1858); Henry Rathbun (assistant, 1857); Silas Gardner Shaw (1858-1862 and 1863-1869); E. E. Taylor (assistant, 1859); William Spooner (assistant, 1859); William H. Carr (1859-1862); Benjamin W. Walker (assistant, c. 1862); William D. Weeden (1862); Albert Caswell (assistant, 1862); Peter Lee (1862-1863); Christopher Austen (assistant, 1863); William Batchelder (assistant, 1863-1864); Ann N. Shaw (assistant, 1864-1869); Thomas King (1869-1873?); Andrew King (assistant, 1869); W. W. Wales (1873-1895); Charles H. Lake (assistant 1875); George A. Brown (assistant, 1875-1885); John S. Wales (assistant 1885-1888); George B. Wales (assistant 1888-1895, head keeper 1895-1913?); George T. Manders (assistant 1913-1919; principal keeper 1919-1937); Stanley Roode (assistant, 1919-1920); Carl Chellis (1938-1945); Edward A. Donahue (assistant 1920-1947, principal keeper 1948-1953); Ronald Bugenske (Coast Guard assistant 1962–1965); Calvin Hirsch (Coast Guard assistant 1965–1969); Dominic Turillo (Coast Guard assistant 1951-1953, then officer in charge, 1954-1969); John K. Martin (Coast Guard, 1969); George Light (Coast Guard 1969-1972); John Baxter (Coast Guard, 1970-1972)