History of Duxbury Pier Light, Duxbury, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

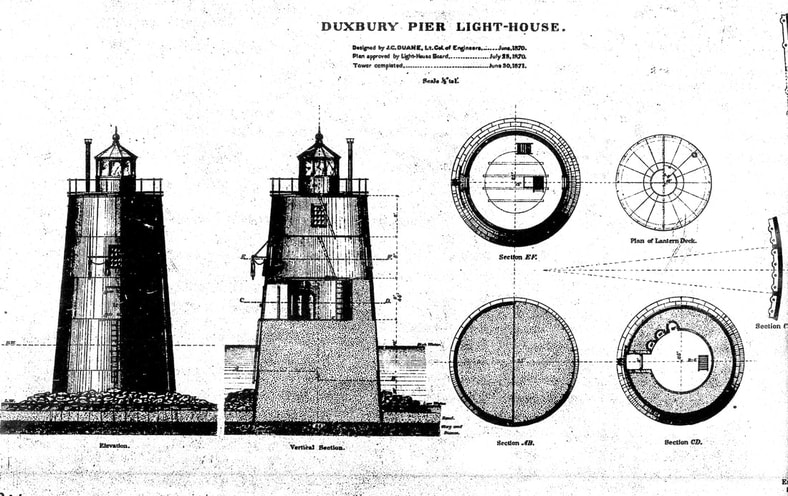

This stout, coffeepot-shaped lighthouse, known fondly to locals as "Bug Light," or simply "The Bug," occupies an important niche in lighthouse history as the first offshore cast-iron caisson lighthouse in the United States.

Despite its tubby appearance, it's a thing of beauty to the band of plucky preservationists who've saved it from the scrap heap.

Congress appropriated $17,931 on July 15, 1870, for the establishment of a lighthouse to mark a dangerous shoal off Saquish Head in Plymouth Bay, on the north side of the main channel to the harbors of Plymouth, Duxbury, and Kingston.

Left: When the lighthouse was first built there were no outside decks. (From Stebbins' Illustrated Coast Pilot, 1902.)

Congress appropriated $17,931 on July 15, 1870, for the establishment of a lighthouse to mark a dangerous shoal off Saquish Head in Plymouth Bay, on the north side of the main channel to the harbors of Plymouth, Duxbury, and Kingston.

Left: When the lighthouse was first built there were no outside decks. (From Stebbins' Illustrated Coast Pilot, 1902.)

A local resident named William W. Burgess, Jr. later described his involvement in the construction of Duxbury Pier Lighthouse:

In April '71 they decided to build an iron lighthouse near the Duxbury Pier on the flats close to the edge of the channel, and my father and contracted with the Government Inspector to build it. It was built of iron plates, 10 feet long with flanges on each to bolt them together and form a circle 28 feet in diameter at the bottom. This section was put together in North Dock and a cofferdam built inside of it to float it, and one Sunday we towed it down with the government schooner and our sloop Rose Wood, placed it in position then broke in the cofferdam and sunk it. I got $3.00 for my part of the job, which was looking on.

The lighthouse, 47 feet in height overall, was filled with concrete to a height of 25 feet. The tower contained three levels below the lantern, including two levels that served as living quarters.

The lighthouse, 47 feet in height overall, was filled with concrete to a height of 25 feet. The tower contained three levels below the lantern, including two levels that served as living quarters.

The lantern held a fifth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light 35 feet above mean high water, first exhibited on September 15, 1871. The first keeper was William Atwood, who stayed until 1878.

To protect the structure, 100 tons of stones were placed around the base in 1886, and another 175 tons were added in 1890. A lower gallery and roof were added in 1897. A 700-gallon water cistern was added in 1900, and a fog bell and striking apparatus were installed in 1902.

Keeper Tolman Spencer left the lighthouse in the early afternoon on December 27, 1920, to go to a movie with his wife on the mainland. He returned to the lighthouse, but after dark, when his wife looked out, she saw that the light was not on. A crew from the lifesaving station at the Gurnet investigated and found that Spencer was not at the lighthouse.

Later that night, as it grew very cold and windy, a police boat sighted Spencer's dory. They found the keeper rowing against the wind and tide, not making any headway. Spender was pulled into the police boat and immediately collapsed from exhaustion. The keeper's wife was taken to the lighthouse with him, and he was said to be fine by the next day.

Frank A. Grieder, a Maine native, became keeper in 1930. The Grieders brought their belongings from Maine to Plymouth in a Model A Ford, and the keeper's wife and children took up residence in the Rocky Nook section of the city. In an interview in 2000, Grieder's son, Bill, remembered his father's days as keeper of "The Bug."

The thing that I used to get a big kick out of was when it came in foggy. We had a huge brass bell up on the tower, and it worked like clockwork. You'd wind it up, and it had a big hammer. You'd wind and wind and all of a sudden it'd go "whammo!" and the whole tower would shake. You'd lie there at night and wonder, "How am I going to sleep?" And next thing you know you'd gotten used to it. And when the fog cleared and they shut the bell off, you woke up.

At low tide you could walk around there and pick up lobsters and sea clams. Of course if you were out on the flats you always kept your eye on the tide because it came up quite quickly.

Fred Bohm, later at Deer Island Light in Boston Harbor, was keeper in the late 1930s into the 1940s. The historian Edward Rowe Snow claimed that Bohm rescued 90 people from drowning in a single year, including 36 Girl Scouts.

Keeper Tolman Spencer left the lighthouse in the early afternoon on December 27, 1920, to go to a movie with his wife on the mainland. He returned to the lighthouse, but after dark, when his wife looked out, she saw that the light was not on. A crew from the lifesaving station at the Gurnet investigated and found that Spencer was not at the lighthouse.

Later that night, as it grew very cold and windy, a police boat sighted Spencer's dory. They found the keeper rowing against the wind and tide, not making any headway. Spender was pulled into the police boat and immediately collapsed from exhaustion. The keeper's wife was taken to the lighthouse with him, and he was said to be fine by the next day.

Frank A. Grieder, a Maine native, became keeper in 1930. The Grieders brought their belongings from Maine to Plymouth in a Model A Ford, and the keeper's wife and children took up residence in the Rocky Nook section of the city. In an interview in 2000, Grieder's son, Bill, remembered his father's days as keeper of "The Bug."

The thing that I used to get a big kick out of was when it came in foggy. We had a huge brass bell up on the tower, and it worked like clockwork. You'd wind it up, and it had a big hammer. You'd wind and wind and all of a sudden it'd go "whammo!" and the whole tower would shake. You'd lie there at night and wonder, "How am I going to sleep?" And next thing you know you'd gotten used to it. And when the fog cleared and they shut the bell off, you woke up.

At low tide you could walk around there and pick up lobsters and sea clams. Of course if you were out on the flats you always kept your eye on the tide because it came up quite quickly.

Fred Bohm, later at Deer Island Light in Boston Harbor, was keeper in the late 1930s into the 1940s. The historian Edward Rowe Snow claimed that Bohm rescued 90 people from drowning in a single year, including 36 Girl Scouts.

One windy night Bohm heard a scream for help. He rushed out to see a woman swimming toward the lighthouse from her capsized boat.

Not able to row to her in time, Bohm dove into the water and swam to the woman, who was unconscious by the time he reached her. Bohm brought the woman back to the lighthouse where she gradually came to. In her struggle to stay afloat she had lost her bathing suit.

As she regained consciousness, the woman's first words were, "Where are my clothes?" Keeper Bohm answered, "I don't know, but you're lucky to be alive." Later that night the woman was safely ashore with borrowed clothes.

In December 1942, Bohm and a companion were heading for the mainland to pick up provisions, but nearly drowned when their boat began to leak. A lobsterman rescued the pair, but the keeper lost two fingers from frostbite.

Coast Guardsman Harry Salter was keeper at "The Bug" in 1944. He has written a booklet about his time at "The Bug," called simply Bug Light. Salter was at Duxbury Pier Light when the hurricane of September 1944 hit, battering the isolated station with 30-foot waves. He described the scene:

As she regained consciousness, the woman's first words were, "Where are my clothes?" Keeper Bohm answered, "I don't know, but you're lucky to be alive." Later that night the woman was safely ashore with borrowed clothes.

In December 1942, Bohm and a companion were heading for the mainland to pick up provisions, but nearly drowned when their boat began to leak. A lobsterman rescued the pair, but the keeper lost two fingers from frostbite.

Coast Guardsman Harry Salter was keeper at "The Bug" in 1944. He has written a booklet about his time at "The Bug," called simply Bug Light. Salter was at Duxbury Pier Light when the hurricane of September 1944 hit, battering the isolated station with 30-foot waves. He described the scene:

The gigantic waves were hammering this stout little light station unmercifully. It shook so bad we had trouble keeping the oil lamps lit... The heavy seas on the east side were striking against the light, then crashing up under the catwalk and tearing away at our boat that we had previously lashed high on the davits.

U.S. Coast Guard

Salter went out on the deck in an effort to secure the boat. A wave opened the trap door near him and Salter fell through. Fortunately another wave drove Salter against the ladder, and he was able to climb to safety. Salter gave up on saving the boat and watched the hurricane from inside the tower for the next few hours. He and the other keepers surveyed the damage later and found that the boat, the fog bell mechanism, and the outhouse were all gone.

The lighthouse was automated in 1964 and the keepers were removed. A modern optic replaced the Fresnel lens. Over the next two decades Duxbury Pier Light fell victim to much vandalism and seabirds made themselves a home in the interior.

The lighthouse was automated in 1964 and the keepers were removed. A modern optic replaced the Fresnel lens. Over the next two decades Duxbury Pier Light fell victim to much vandalism and seabirds made themselves a home in the interior.

In 1983, the lighthouse was slated by the Coast Guard to be replaced by a fiberglass tower much like the one that had replaced Boston Harbor's old Deer Island Lighthouse.

Part of the structure before renovation (U.S. Coast Guard)

The Coast Guard had estimated that a renovation of the current structure would have cost $250,000. A group of concerned local residents formed Project Bug Light.

Aided by Congressman Gerry Studds, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, and State Senator Edward P. Kirby, the group convinced the Coast Guard to alter their plans. A five-year lease was granted to the preservation committee.

The Coast Guard sandblasted and painted the structure and did some repair work in 1983; the work was completed in 1985. The Coast Guard spent $100,000 to refurbish the lower half of the lighthouse.

Aided by Congressman Gerry Studds, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, and State Senator Edward P. Kirby, the group convinced the Coast Guard to alter their plans. A five-year lease was granted to the preservation committee.

The Coast Guard sandblasted and painted the structure and did some repair work in 1983; the work was completed in 1985. The Coast Guard spent $100,000 to refurbish the lower half of the lighthouse.

Project Bug Light raised $20,000 from local businesses, as well as sales of T-shirts and bumper stickers, a fashion show, baseball games, and raffling a painting. They used this money to restore the upper parts and the interior, including the rebuilding of the roof and the catwalk.

At the same time, solar power replaced the older battery system. The fog signal was also converted to solar power.

Left: Before the repainting of the tower's interior in 2001, you could still see the outline of the kitchen sink on an inside wall.

In the late 1980s vandals broke into the lantern room, leaving it susceptible to leaks. The weather deteriorated the wood interior so much that all the wood had to be removed, leaving bare iron walls.

After a few years Project Bug Light virtually dissolved as an organization, and the five-year lease expired. In 1993 the Coast Guard again talked of replacing the lighthouse with a fiberglass pole, or at least removing the lantern room. This time Dr. Don Muirhead of Duxbury, an avid sailor, spearheaded a new preservation effort. The Coast Guard again refurbished the lighthouse in 1996.

Project Bug Light is now responsible for the care of Plymouth ("Gurnet") Light as well, and they have changed the name of the organization to match the mission.

Left: Before the repainting of the tower's interior in 2001, you could still see the outline of the kitchen sink on an inside wall.

In the late 1980s vandals broke into the lantern room, leaving it susceptible to leaks. The weather deteriorated the wood interior so much that all the wood had to be removed, leaving bare iron walls.

After a few years Project Bug Light virtually dissolved as an organization, and the five-year lease expired. In 1993 the Coast Guard again talked of replacing the lighthouse with a fiberglass pole, or at least removing the lantern room. This time Dr. Don Muirhead of Duxbury, an avid sailor, spearheaded a new preservation effort. The Coast Guard again refurbished the lighthouse in 1996.

Project Bug Light is now responsible for the care of Plymouth ("Gurnet") Light as well, and they have changed the name of the organization to match the mission.

Founder Don Muirhead died in 2000, but the volunteers of Project Gurnet & Bug Lights, Inc. continue to do maintenance at the light and to raise funds toward the continued preservation of "The Bug."

In the fall of 2001 Project Gurnet & Bug Lights, Inc. hired the Campbell Construction Group of Beverly, Massachusetts for another major renovation of the lighthouse.

Joints in the caisson were repaired by caulking and welding, and over 1,200 pounds of rust was removed from the lighthouse. All the paint was removed inside and out, and three new coats of paint were added. In addition, several inches of guano were removed.

A new restoration effort was mounted in the summer of 2010. Early in the summer, Project Gurnet and Bug Light restored the windows and doors of the lower level and rusted railings around the lower gallery. Scott Day, vice president of Project Gurnet and Bug Light in charge of building maintenance, said the rest of the work would involve mooring a large barge near the lighthouse. The entire structure was to be repainted after the removal of rust and barnacles.“It will give us a guaranteed life of at least 10 years and maybe a useful life of 15 years,” Day told a reporter.

Duxbury Pier Light remains an active aid to navigation. While it can be seen distantly from the Plymouth waterfront, it is best viewed from the harbor cruises and whale watches out of Plymouth.

For more information or to support the preservation of Duxbury Pier Light, contact Project Gurnet & Bug Lights, Inc.

Joints in the caisson were repaired by caulking and welding, and over 1,200 pounds of rust was removed from the lighthouse. All the paint was removed inside and out, and three new coats of paint were added. In addition, several inches of guano were removed.

A new restoration effort was mounted in the summer of 2010. Early in the summer, Project Gurnet and Bug Light restored the windows and doors of the lower level and rusted railings around the lower gallery. Scott Day, vice president of Project Gurnet and Bug Light in charge of building maintenance, said the rest of the work would involve mooring a large barge near the lighthouse. The entire structure was to be repainted after the removal of rust and barnacles.“It will give us a guaranteed life of at least 10 years and maybe a useful life of 15 years,” Day told a reporter.

Duxbury Pier Light remains an active aid to navigation. While it can be seen distantly from the Plymouth waterfront, it is best viewed from the harbor cruises and whale watches out of Plymouth.

For more information or to support the preservation of Duxbury Pier Light, contact Project Gurnet & Bug Lights, Inc.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William Atwood (1871-1878); John A. Richmond Jr. (assistant 1872-1873); Oscar Marsh (assistant 1873-1874); S. J. Atwood (wife of William) (assistant 1874-1878); George Manter (1878-1881); Milton Reamy (assistant 1878-1881); Benjamin B. Manter (1881-1884); Henry H. Sampson (assistant 1881-1882); Edward L. Gorham (1884-1887); Amasa S. Dyer (1887-1888); James H. Bagnall (1888-1891); Michael J. Curran (1891-1892); Edwin F. King Jr. (1892-1895); George A. Jamieson (1895-1897); Mills Gunderson (1897-1902); Joseph F. Woods (1902-1903); Willis Higgins (1903-1904); George E. Kezer (1904-1909); George E. Howard (1909-1910); Fred C. Brown (1910-?); Frank Allen Davis (?-1920); Tolman Spencer (1920-?); Frank A. Grieder (1930-1934); Fred Bohm (c. 1930s); Homer Hathaway (1942-1943); Harry Salter (Coast Guard, c. 1944); ? Jovie (Coast Guard, c. 1943); Ellis Woods (Coast Guard, c. 1943); Robert Wascko (Coast Guard, 1958-1959)

William Atwood (1871-1878); John A. Richmond Jr. (assistant 1872-1873); Oscar Marsh (assistant 1873-1874); S. J. Atwood (wife of William) (assistant 1874-1878); George Manter (1878-1881); Milton Reamy (assistant 1878-1881); Benjamin B. Manter (1881-1884); Henry H. Sampson (assistant 1881-1882); Edward L. Gorham (1884-1887); Amasa S. Dyer (1887-1888); James H. Bagnall (1888-1891); Michael J. Curran (1891-1892); Edwin F. King Jr. (1892-1895); George A. Jamieson (1895-1897); Mills Gunderson (1897-1902); Joseph F. Woods (1902-1903); Willis Higgins (1903-1904); George E. Kezer (1904-1909); George E. Howard (1909-1910); Fred C. Brown (1910-?); Frank Allen Davis (?-1920); Tolman Spencer (1920-?); Frank A. Grieder (1930-1934); Fred Bohm (c. 1930s); Homer Hathaway (1942-1943); Harry Salter (Coast Guard, c. 1944); ? Jovie (Coast Guard, c. 1943); Ellis Woods (Coast Guard, c. 1943); Robert Wascko (Coast Guard, 1958-1959)