History of Tongue Point Lighthouse, Bridgeport, Connecticut

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont.

Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without

permission of the author.

From early shipbuilding and whaling to manufacturing and coastal trade, Bridgeport owed its development to a large harbor at the mouth of the Pequonnock River on Long Island Sound.

U.S. Coast Guard

Today, Bridgeport Harbor

is one of only three deepwater ports in Connecticut.

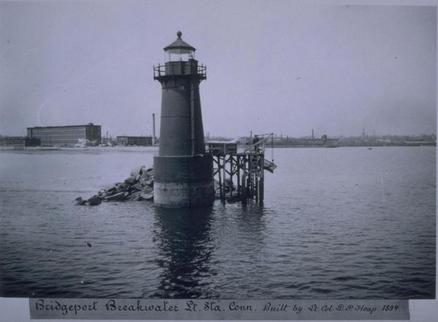

In 1891, the same year the city’s favorite son P. T. Barnum died, a breakwater was built at Tongue Point at the west side of the entrance to the inner harbor, providing a harbor of refuge. Federal appropriations in 1893-94 totaling $4,500 were secured for the installation of a lighthouse at the end of this breakwater, extending out from Tongue Point (also known as Wells Point), about 500 feet from shore.

The tower, constructed under the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel D. P. Heap of the Lighthouse Board, is a smaller example of the prefabricated cast-iron lighthouses erected at many locations from the 1870s to the early 1900s.

The 31-foot tower (22 feet to the base of the lantern deck) is about 12 feet in diameter at its base. A spiral stairway leads from the base to the watch room, and from there a ladder reaches into the octagonal iron lantern. Unlike most similar towers, this one is not lined with brick.

On March 1, 1895, the sixth-order Fresnel lens in the lighthouse was lighted for the first time, replacing a temporary lantern that had been in use since the beginning of the previous year. A keeper’s dwelling was never erected at this location, as the authorities apparently felt it was close enough to shore to make a resident keeper an unnecessary expense. It was first put under the charge of the longtime keeper of Bridgeport Harbor Lighthouse, S. Adolphus McNeil. McNeil’s father had been responsible for establishing the first light in Bridgeport Harbor, and his brother John was harbormaster at the time Tongue Point Lighthouse went into service.

In 1891, the same year the city’s favorite son P. T. Barnum died, a breakwater was built at Tongue Point at the west side of the entrance to the inner harbor, providing a harbor of refuge. Federal appropriations in 1893-94 totaling $4,500 were secured for the installation of a lighthouse at the end of this breakwater, extending out from Tongue Point (also known as Wells Point), about 500 feet from shore.

The tower, constructed under the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel D. P. Heap of the Lighthouse Board, is a smaller example of the prefabricated cast-iron lighthouses erected at many locations from the 1870s to the early 1900s.

The 31-foot tower (22 feet to the base of the lantern deck) is about 12 feet in diameter at its base. A spiral stairway leads from the base to the watch room, and from there a ladder reaches into the octagonal iron lantern. Unlike most similar towers, this one is not lined with brick.

On March 1, 1895, the sixth-order Fresnel lens in the lighthouse was lighted for the first time, replacing a temporary lantern that had been in use since the beginning of the previous year. A keeper’s dwelling was never erected at this location, as the authorities apparently felt it was close enough to shore to make a resident keeper an unnecessary expense. It was first put under the charge of the longtime keeper of Bridgeport Harbor Lighthouse, S. Adolphus McNeil. McNeil’s father had been responsible for establishing the first light in Bridgeport Harbor, and his brother John was harbormaster at the time Tongue Point Lighthouse went into service.

After a $1,200 appropriation in 1897, an electrically operated “fog gong” was established at the station.

U.S. Coast Guard

This apparatus proved unreliable and

it was replaced in 1899 by a 160-pound bell, mounted on the side of the

tower, along with a new clockwork-operated striking mechanism.

Shortly after the turn of the century, McNeil gave up his duties as keeper of Bridgeport Harbor Light, moving to shore and concentrating on the care of the light at Tongue Point.

Tending the little light on the breakwater was easy enough in fair weather, but walking out on the breakwater or reaching the station by boat could be hair-raising in times of heavy seas or fog, in spite of the addition of a landing wharf in 1896 and a plank walkway on the breakwater in 1900.

Shortly after the turn of the century, McNeil gave up his duties as keeper of Bridgeport Harbor Light, moving to shore and concentrating on the care of the light at Tongue Point.

Tending the little light on the breakwater was easy enough in fair weather, but walking out on the breakwater or reaching the station by boat could be hair-raising in times of heavy seas or fog, in spite of the addition of a landing wharf in 1896 and a plank walkway on the breakwater in 1900.

The 1905 Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board noted the following:

The

keeper has erected at his own expense a small shanty in which he sleeps

nightly that he may be ready to start the fog-signal machinery at

shortest notice. There is no other dwelling for the keeper at

this station, and although his family lives in another part of

Bridgeport he is compelled to stay in this shanty nightly and the

greater part of each day. It is estimated that a proper piece of

land can be bought and a proper dwelling erected for $5,000.

No appropriation was made, and no dwelling was ever constructed. Even if it had been built, it would have been too late for S. Adolphus McNeil. McNeil died in December 1904 and was replaced by his widow, Flora Evans McNeil, at $300 per year. “When he died I asked for it, “she was quoted in a newspaper article, “and although they were already giving up the idea of allowing women to become lighthouse keepers they knew that I had actually been the keeper of the light for 20 years and I was allowed to retain it without even an examination.”

As a young girl, Flora had accompanied her sea captain father, John Evans, on a trip to South America, and she mastered the art of navigation at his side. Described in a newspaper article as “a woman of attractive personality, a successful business manager, an interesting conversationalist and an aspirant for the vote,” Ms. McNeil earned much respect during her years as a lightkeeper and local businesswoman.

No appropriation was made, and no dwelling was ever constructed. Even if it had been built, it would have been too late for S. Adolphus McNeil. McNeil died in December 1904 and was replaced by his widow, Flora Evans McNeil, at $300 per year. “When he died I asked for it, “she was quoted in a newspaper article, “and although they were already giving up the idea of allowing women to become lighthouse keepers they knew that I had actually been the keeper of the light for 20 years and I was allowed to retain it without even an examination.”

As a young girl, Flora had accompanied her sea captain father, John Evans, on a trip to South America, and she mastered the art of navigation at his side. Described in a newspaper article as “a woman of attractive personality, a successful business manager, an interesting conversationalist and an aspirant for the vote,” Ms. McNeil earned much respect during her years as a lightkeeper and local businesswoman.

A 1913 article described Flora McNeil bundled in a rubber coat and hat and high rubber boots, scurrying along the plank walkway on the breakwater to reach the lighthouse through high wind and rain.

U.S. Coast Guard

She

downplayed the hazards of the job:

As a rule, there is nothing really interesting about the work. Of course, during a heavy storm it isn’t exactly fun to take a trip out to the lighthouse, but the light must be going and the worse the weather the more necessary for it to be going. The tides have been very high of late and during a severe storm the waves and water get up to the plank… Usually it is simply a matter of going out at sunrise to turn off the light and at sunset to light it. If there is a storm or a fog the bell, too, must be turned on. I have gone out in the middle of the night to start the fog bell, but as a rule I have had someone go with me.

She did admit, however, that it could be dangerous at times.

I think perhaps the hardest trips are the ones made in winter when it has rained and turned cold for the plank is then a glare of ice and naturally very slippery. I have been out during snowstorms when the plank was so slippery it was scarcely possible to keep your footing and when the storm was so heavy that all you could see in front of you was the falling snow. You could hear the roar of water under your feet and see the snow melt as it touched the waves but you could hardly more than guess where to put your next step.

Flora McNeil lived on Lafayette Street in Bridgeport. She ran a manicurist business in the Meigs Building in the city, practically leading a double life as a well-dressed and groomed businesswoman by day, dedicated lightkeeper in her off hours. An expert boater, Flora claimed the sea never frightened her.

It isn’t exactly a pleasure to take a trip out there when a fog is coming on or when a heavy snow is falling with it so dark you can hardly see your hand before your face. You can hear the moaning water on either side of you and if you were on some desert island you could not feel more alone and forsaken by all humanity. There is not a sign of human life, the wind whistles and moans, the waters lap the rocks wildly and the rain beats into your face. I suppose some people would think it an impossible thing to do – and probably it would be impossible for them – but I am almost as much at home on or in the water as I am on land and I have no real fear of the water even when it is angry.

The breakwater at Tongue Point was never popular with the captains of large vessels, who complained about the sharp turn they had to make as they rounded the breakwater to enter the inner harbor. In 1919, the situation was remedied by the removal of 350 feet of the breakwater. The granite that was removed was added to the tops of two breakwaters at each side of the entrance to the harbor.

When the breakwater was shortened, a derrick was used to move the lighthouse onto a new ten-foot high concrete foundation at its present position, 275 feet closer to shore. The harbor was dredged and widened around the same time.

As a rule, there is nothing really interesting about the work. Of course, during a heavy storm it isn’t exactly fun to take a trip out to the lighthouse, but the light must be going and the worse the weather the more necessary for it to be going. The tides have been very high of late and during a severe storm the waves and water get up to the plank… Usually it is simply a matter of going out at sunrise to turn off the light and at sunset to light it. If there is a storm or a fog the bell, too, must be turned on. I have gone out in the middle of the night to start the fog bell, but as a rule I have had someone go with me.

She did admit, however, that it could be dangerous at times.

I think perhaps the hardest trips are the ones made in winter when it has rained and turned cold for the plank is then a glare of ice and naturally very slippery. I have been out during snowstorms when the plank was so slippery it was scarcely possible to keep your footing and when the storm was so heavy that all you could see in front of you was the falling snow. You could hear the roar of water under your feet and see the snow melt as it touched the waves but you could hardly more than guess where to put your next step.

Flora McNeil lived on Lafayette Street in Bridgeport. She ran a manicurist business in the Meigs Building in the city, practically leading a double life as a well-dressed and groomed businesswoman by day, dedicated lightkeeper in her off hours. An expert boater, Flora claimed the sea never frightened her.

It isn’t exactly a pleasure to take a trip out there when a fog is coming on or when a heavy snow is falling with it so dark you can hardly see your hand before your face. You can hear the moaning water on either side of you and if you were on some desert island you could not feel more alone and forsaken by all humanity. There is not a sign of human life, the wind whistles and moans, the waters lap the rocks wildly and the rain beats into your face. I suppose some people would think it an impossible thing to do – and probably it would be impossible for them – but I am almost as much at home on or in the water as I am on land and I have no real fear of the water even when it is angry.

The breakwater at Tongue Point was never popular with the captains of large vessels, who complained about the sharp turn they had to make as they rounded the breakwater to enter the inner harbor. In 1919, the situation was remedied by the removal of 350 feet of the breakwater. The granite that was removed was added to the tops of two breakwaters at each side of the entrance to the harbor.

When the breakwater was shortened, a derrick was used to move the lighthouse onto a new ten-foot high concrete foundation at its present position, 275 feet closer to shore. The harbor was dredged and widened around the same time.

The light was automated in 1954. The Coast Guard proposed discontinuing the light and fog signal in 1967, but local protests saved “Bug Light,” as it’s known locally.

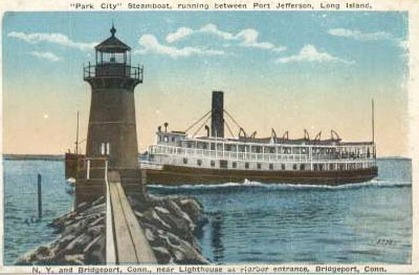

The Bridgeport to Port Jefferson ferry

On June 4, 2004, it was announced that the lighthouse had been determined to be excess to the needs of the U.S. Coast Guard and that it would be made available to an eligible entity pursuant to the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. The area around the lighthouse is off limits to the public because it's on the restricted grounds of a power plant owned by Wisvest-Connecticut LLC. Because of the access issues, the lighthouse was pulled off the list to be transferred.

It’s hard to get a good view of this lighthouse from land. It can be seen closely from the decks of the Bridgeport to Port Jefferson ferry.

Today, the solar powered light, flashing green every four seconds, continues as an aid to navigation. The sixth-order lens has been replaced by a modern optic and there is no longer a fog signal at the site.

Keepers: C. Adolphus McNeil (1895-1904), Flora McNeil (1904-1920), Frank Evans (lamplighter or attendant, c. 1939 to at least 1940), Charles Baker (lamplighter or attendant, c. 1950s-1980s)

It’s hard to get a good view of this lighthouse from land. It can be seen closely from the decks of the Bridgeport to Port Jefferson ferry.

Today, the solar powered light, flashing green every four seconds, continues as an aid to navigation. The sixth-order lens has been replaced by a modern optic and there is no longer a fog signal at the site.

Keepers: C. Adolphus McNeil (1895-1904), Flora McNeil (1904-1920), Frank Evans (lamplighter or attendant, c. 1939 to at least 1940), Charles Baker (lamplighter or attendant, c. 1950s-1980s)