History of Baker Island Light, Islesford, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

One-hundred-twenty-three-acre Baker Island, about four miles southeast of Mount Desert Island, is one of five islands that make up the Cranberry Isles, named for the low-bush cranberries that proliferate in autumn.

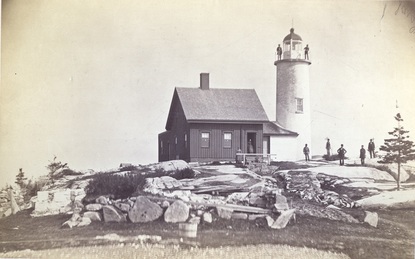

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

The year-round population of the islands is about 120, but the numbers swells to around 600 in summer.

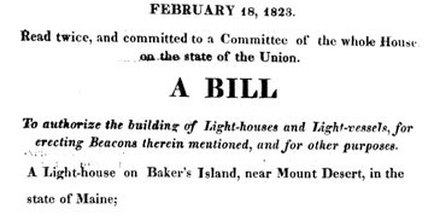

Because of dangerous ledges and a sandbar nearby, and to help mark the western approach to Frenchman Bay, Congress appropriated $2.500 for the building of a lighthouse on the island in 1823.

The project stalled and the funds had to be reappropriated in 1826, and an additional $1,300 was authorized for the completion of the station in 1828.

Built on the highest point on the island, it was the earliest light station in the Mount Desert area.

Because of dangerous ledges and a sandbar nearby, and to help mark the western approach to Frenchman Bay, Congress appropriated $2.500 for the building of a lighthouse on the island in 1823.

The project stalled and the funds had to be reappropriated in 1826, and an additional $1,300 was authorized for the completion of the station in 1828.

Built on the highest point on the island, it was the earliest light station in the Mount Desert area.

The first lighthouse was a 26-foot rubblestone tower with an octagonal wrought-iron lantern, with which housed 10 whale oil–fueled lamps and 15-inch reflectors showing a fixed white light. A four-room dwelling with an attached kitchen was built near the tower.

William and Hannah Gilley took possession of Baker Island in the early 1800s. William Gilley’s father, a native of England, was one of the earliest settlers of Mount Desert Island. William and Hannah had three children and would eventually have nine more during their years on Baker Island. On their small island farm, the family kept several cows, a yoke of oxen, about 50 sheep, chickens, and several hogs. Most of the family’s clothes were made from wool from their own sheep.

When the lighthouse was built, William Gilley was appointed as keeper at a salary of $350 per year. He was described as a large, strong man, six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds. One of the Gilleys’ sons was the subject of an 1899 publication by Charles W. Elliot, called John Gilley: One of the Forgotten Millions. Elliot described the remarkable self-reliance of the Gilley family:

It is obvious that this family on its island domain was much more self-contained and independent than any ordinary family is today, even under similar circumstances. They got their fuel, food, and clothing as products of their own skill and labor, their supplies and resources being almost all derived from the sea and from their own fields and woods.

When the lighthouse was built, William Gilley was appointed as keeper at a salary of $350 per year. He was described as a large, strong man, six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds. One of the Gilleys’ sons was the subject of an 1899 publication by Charles W. Elliot, called John Gilley: One of the Forgotten Millions. Elliot described the remarkable self-reliance of the Gilley family:

It is obvious that this family on its island domain was much more self-contained and independent than any ordinary family is today, even under similar circumstances. They got their fuel, food, and clothing as products of their own skill and labor, their supplies and resources being almost all derived from the sea and from their own fields and woods.

Gilley was still in charge when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited for his survey of 1843. Lewis found the walls of the tower cracked and leaky.

A rocky beach on the island

The lime mortar was of poor quality, and the base of the tower rested on the natural surface of the ledge with and had no proper foundation. The interior was frequently coated with ice in winter. The roof of the dwelling was rotten, according to Lewis, and the kitchen wing—which had been rebuilt only five years earlier—had “settled away from” the rest of the dwelling.

Lewis also offered the opinion that the lighthouse had been badly situated: “It should have been placed on either the Great Duck or Long Island, which are the two most southerly and prominent of the group [of islands]. . . . In running east for Baker’s Island, vessels are liable to get ashore on Long Island reef or the Great Duck, before seeing the light.” It would be almost a half -century before Great Duck Island, some five miles south of the Cranberry Isles, got its lighthouse.

Lewis also offered the opinion that the lighthouse had been badly situated: “It should have been placed on either the Great Duck or Long Island, which are the two most southerly and prominent of the group [of islands]. . . . In running east for Baker’s Island, vessels are liable to get ashore on Long Island reef or the Great Duck, before seeing the light.” It would be almost a half -century before Great Duck Island, some five miles south of the Cranberry Isles, got its lighthouse.

Gilley remained keeper until July 1849, when he was dismissed for not being a member of the party that had come into power, the Whigs.

U.S. Coast Guard photo, circa late 1800s

According to Charles W. Elliot, it was suggested that Gilley become a Whig so he could keep his position. “To this overture he replied, with some expletives,” Elliot wrote, “that he would not change his political connection for all the lighthouses in the United States.” At 63, Gilley left Baker Island and moved to Great Duck Island, which he had purchased in 1837 for $300.

Two of William Gilley’s sons stayed on Baker Island, and they were accused of harassing the next keeper, John Rich, and the succeeding keeper, Joseph Bunker. W. B. Franklin, an inspector for the First District, wrote of the Gilley brothers in December 1853: “They allow cattle to graze there, and receive money for the use of the land which the light keeper is entitled to if any one is. They have been ordered to leave repeatedly but have always refused to go, threatening to use force, and are very abusive.” Franklin suggested that the Gilleys’ houses should be torn down. The presence of a revenue cutter might be needed, he said, “to have the business thoroughly done.”

Two of William Gilley’s sons stayed on Baker Island, and they were accused of harassing the next keeper, John Rich, and the succeeding keeper, Joseph Bunker. W. B. Franklin, an inspector for the First District, wrote of the Gilley brothers in December 1853: “They allow cattle to graze there, and receive money for the use of the land which the light keeper is entitled to if any one is. They have been ordered to leave repeatedly but have always refused to go, threatening to use force, and are very abusive.” Franklin suggested that the Gilleys’ houses should be torn down. The presence of a revenue cutter might be needed, he said, “to have the business thoroughly done.”

The federal government filed suit against the Gilley brothers in 1854, but the Gilleys countered by claiming that they owned the island. In October 1855 an agreement was reached that gave the government a 40-rod- square lot around the light station and, the right of way from the boat landing to the station, and the right for the keeper to pasture animals “on any and all the lands on said Island.”

Circa early 1900s

The 1853 annual report of the new U.S. Lighthouse Board called the lighthouse tower “entirely worthless,” and the dwelling so decrepit and leaky that it was unhealthy.

The extant 43-foot-tall cylindrical tower was built in 1855 after a congressional appropriation of $5,000.

A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed; the lamp was fueled by lard oil. In 1903, a four-inch layer of brick was added to the outside of the tower. There was, for some time, a short covered passageway between the dwelling and the lighthouse, but it has been removed.

An 1886 book, All Among the Lighthouses by Mary Bradford Crowninshield, described Baker Island while Roscoe G. Lopaus was the keeper:

The lighthouse . . . stands up high and bold on a sudden rise of land, and is some distance from the boat landing; and it was a pleasure. . . to walk through the meadows thickly grown with buttercups and daisies. . .

The extant 43-foot-tall cylindrical tower was built in 1855 after a congressional appropriation of $5,000.

A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed; the lamp was fueled by lard oil. In 1903, a four-inch layer of brick was added to the outside of the tower. There was, for some time, a short covered passageway between the dwelling and the lighthouse, but it has been removed.

An 1886 book, All Among the Lighthouses by Mary Bradford Crowninshield, described Baker Island while Roscoe G. Lopaus was the keeper:

The lighthouse . . . stands up high and bold on a sudden rise of land, and is some distance from the boat landing; and it was a pleasure. . . to walk through the meadows thickly grown with buttercups and daisies. . .

Vurney L. King became keeper in 1912. King lived on the island with his wife and children, along with a cow, a pig, and some hens.

King’s daughter, Eleanor, later described attending a little schoolhouse on the island:

When we moved on there, there were 13 pupils. And then it got down to seven. Then it got down to three. And when it got down to three, they closed the school, and my father used to bring us off here [Southwest Harbor] to go to school. I’d get so homesick when he’d bring me off here.

In November 1932, the pregnant wife of Keeper Joseph Muise went into labor during a strong gale. The assistant keeper was on shore leave, so Keeper Muise could not leave his post.

He phoned the Coast Guard station on a neighboring island, and a crew of five launched a lifeboat, picked up Mrs. Muise and headed for Northeast Harbor, 10 miles away. They were still two miles from the town when Mrs. Muise, wrapped in the Coast Guardsmen's jackets, gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

Right: Howard P. Robbins was keeper 1888-1902. (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

In 1953, the wife of the Coast Guard keeper wrote in a newspaper column:

Haven’t had too many summer people on here so far. I don’t blame them for not coming in, all the fog we’ve had. Hope the fog goes away pretty soon so we’ll know there are other people on this good earth besides ourselves.

When we moved on there, there were 13 pupils. And then it got down to seven. Then it got down to three. And when it got down to three, they closed the school, and my father used to bring us off here [Southwest Harbor] to go to school. I’d get so homesick when he’d bring me off here.

In November 1932, the pregnant wife of Keeper Joseph Muise went into labor during a strong gale. The assistant keeper was on shore leave, so Keeper Muise could not leave his post.

He phoned the Coast Guard station on a neighboring island, and a crew of five launched a lifeboat, picked up Mrs. Muise and headed for Northeast Harbor, 10 miles away. They were still two miles from the town when Mrs. Muise, wrapped in the Coast Guardsmen's jackets, gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

Right: Howard P. Robbins was keeper 1888-1902. (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

In 1953, the wife of the Coast Guard keeper wrote in a newspaper column:

Haven’t had too many summer people on here so far. I don’t blame them for not coming in, all the fog we’ve had. Hope the fog goes away pretty soon so we’ll know there are other people on this good earth besides ourselves.

The light was deactivated in October 1955, but it was re-established in early 1957 as an automatic, unattended light for the benefit of local fishermen and pleasure boaters.

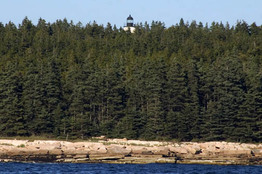

In 1989, the Maine Historic Preservation Commission refurbished the light station at a cost of $3,600. In 1991, the Coast Guard proposed to discontinue the light; tall surrounding trees made it difficult or impossible to see from the water. More than 150 complaints convinced the Coast Guard to keep the light active.

The Coast Guard again proposed discontinuing the light in 1997. A letter writing campaign convinced them that the light was still needed by local mariners.

Many trees were cleared in 2012-13, meaning the light is still visible from the sea. The reduction in the number of trees also lessens the chance of wildfires on the island. Click here for more details.

The Coast Guard again proposed discontinuing the light in 1997. A letter writing campaign convinced them that the light was still needed by local mariners.

Many trees were cleared in 2012-13, meaning the light is still visible from the sea. The reduction in the number of trees also lessens the chance of wildfires on the island. Click here for more details.

|

A Fresnel lens removed from Baker Island is now on display at the Fisherman's Museum at Pemaquid Point Light.

|

Listen to an interview with Cornelia Cesari of Keepers of Baker Island on the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, Light Hearted.

Ownership of the lighthouse tower has been transferred to the National Park Service in recent years, while the active light is still maintained by the Coast Guard.

A tour group on Baker Island

A group of concerned citizens, the Keepers of Baker Island, are working for the preservation of the site.

The Bar Harbor Whale Watch Company offers a four-hour narrated tour to Baker Island. Call 888-WHALES-4 or visit www.barharborwhales.com for more information.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William Gilley (1828-1848); John Rich (1849-1853); Joseph Bunker (1853-1860); John Bunker (1860-1861); Freeman G. Young (1861-1867); Alden H. Jordan (1867-1883); Roscoe G. Lopaus (1883-1888); Howard P. Robbins (1888-1902); George Connors (1902-1915); Vurney L. King (1915 - ?); Joseph Muise (1930-1932); Frank Faulkingham (1932-early 1940s); Wayne Edson Holcomb (U.S. Coast Guard, 1944-1945); Sanford W. Colson (c. early 1950s); Ernest Mathie (c. early 1950s); ? Coleman (c. 1950); ? Clements (c. 1953)

The Bar Harbor Whale Watch Company offers a four-hour narrated tour to Baker Island. Call 888-WHALES-4 or visit www.barharborwhales.com for more information.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William Gilley (1828-1848); John Rich (1849-1853); Joseph Bunker (1853-1860); John Bunker (1860-1861); Freeman G. Young (1861-1867); Alden H. Jordan (1867-1883); Roscoe G. Lopaus (1883-1888); Howard P. Robbins (1888-1902); George Connors (1902-1915); Vurney L. King (1915 - ?); Joseph Muise (1930-1932); Frank Faulkingham (1932-early 1940s); Wayne Edson Holcomb (U.S. Coast Guard, 1944-1945); Sanford W. Colson (c. early 1950s); Ernest Mathie (c. early 1950s); ? Coleman (c. 1950); ? Clements (c. 1953)