History of Portland Breakwater Light, South Portland, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

A fierce storm ravaged Portland Harbor in November 1831, destroying wharves and buildings. In response, a 2,500-foot protective breakwater was planned for the south side of the harbor’s entrance, beginning at Stanford Point and extending out over Stanford Ledge.

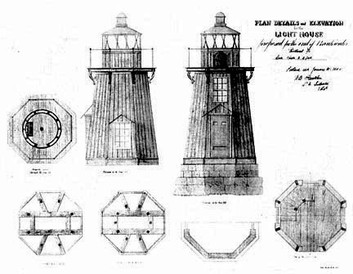

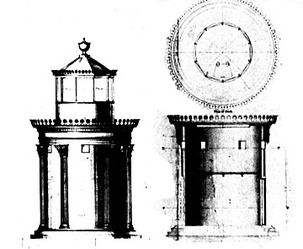

Plans for the first lighthouse. (National Archives)

A lighthouse was included in the plans for the structure.Construction on the breakwater began in 1837, and the foundation was completed by later that year. The breakwater eventually reached 1,800 feet and was uncapped for much of its length. Vessels had to pass through a narrow channel between the breakwater’s end and an obstruction known as Hog Island Ledge. With no lighthouse at its end, the breakwater became more of a navigational hindrance than a help.

In September 1853, Lieut. Thornton A. Jenkins, secretary of the Lighthouse Board, recommended a sixth-order light at the end of the breakwater. “It is absolutely necessary to make a safe entrance into the harbor,” he wrote, “and to guard against striking the breakwater itself, which is nearly under water at high tide, and therefore on dark nights difficult to be seen so as to be avoided.”

The Lighthouse Board asked Congress in 1853 for an appropriation of $3,500 for a lighthouse and keeper’s house, or for $1,000 if it was deemed that no keeper’s house was needed. An appropriation of $3,500 was made on August 3, 1854.

In September 1853, Lieut. Thornton A. Jenkins, secretary of the Lighthouse Board, recommended a sixth-order light at the end of the breakwater. “It is absolutely necessary to make a safe entrance into the harbor,” he wrote, “and to guard against striking the breakwater itself, which is nearly under water at high tide, and therefore on dark nights difficult to be seen so as to be avoided.”

The Lighthouse Board asked Congress in 1853 for an appropriation of $3,500 for a lighthouse and keeper’s house, or for $1,000 if it was deemed that no keeper’s house was needed. An appropriation of $3,500 was made on August 3, 1854.

Construction took about four months during the following year, and on August 1, 1855, a small, octagonal wooden tower went into service.

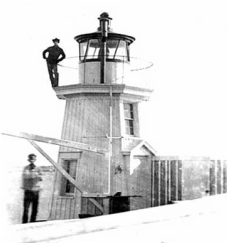

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

The first keeper, W. A. Dyer, illuminated the sixth-order Fresnel lens. The fixed red light was 25 feet above mean high water.

With no keeper’s house, the keeper had to walk over the breakwater to the light. This often became a battle against waves, wind, and ice. Keepers sometimes had to crawl the 1,800 feet to the lighthouse on their hands and knees.

The breakwater was extended by almost 200 feet to the northeast in the early 1870s, and the wooden lighthouse was reported to be decayed and no longer fit for service.

As the work on the breakwater was in progress, the light was shown from a temporary wooden tower.

With no keeper’s house, the keeper had to walk over the breakwater to the light. This often became a battle against waves, wind, and ice. Keepers sometimes had to crawl the 1,800 feet to the lighthouse on their hands and knees.

The breakwater was extended by almost 200 feet to the northeast in the early 1870s, and the wooden lighthouse was reported to be decayed and no longer fit for service.

As the work on the breakwater was in progress, the light was shown from a temporary wooden tower.

|

After a congressional appropriation of $6,000 in June 1874, a new lighthouse was erected on a granite foundation at the end of the structure. The original tower was moved to Little Diamond Island, where it became a lookout tower at a buoy depot (left).

First lighted in June 1875 by Keeper Stephen Hubbard, the new Portland Breakwater Light, known locally as “Bug Light,” was modeled after the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, built in Athens, Greece, in the fourth century B.C. |

The design of the 24-foot-tall (to the tip of the lantern), cast-iron tower is unique. The cylinder, a little less than 12 feet in diameter, is surrounded by six fluted columns.

Plans for the second lighthouse

It has been suggested that Thomas Ustick Walter, who designed the cast-iron dome on the U.S. Capitol building, may have had something to do with designing the lighthouse.

The lighthouse held a sixth-order Fresnel lens. The walk on the breakwater was still difficult, but still no keeper's house was built. The trip out was made somewhat easier by the addition of an iron hand rail on the breakwater, 1,990 feet long, in 1886.

A tiny dwelling, a wood-frame structure with two rooms, was finally built adjacent to the lighthouse in 1889.

The house presented an unusual and precarious-looking appearance as it hung over the edge of the breakwater on both sides. Two more rooms and an attic were added in 1903.

The lighthouse held a sixth-order Fresnel lens. The walk on the breakwater was still difficult, but still no keeper's house was built. The trip out was made somewhat easier by the addition of an iron hand rail on the breakwater, 1,990 feet long, in 1886.

A tiny dwelling, a wood-frame structure with two rooms, was finally built adjacent to the lighthouse in 1889.

The house presented an unusual and precarious-looking appearance as it hung over the edge of the breakwater on both sides. Two more rooms and an attic were added in 1903.

In 1897, a 400-pound fog bell was relocated from the nearby Stanford Ledge Buoy to the breakwater, and new striking machinery was installed by 1899.

Early 1900s

A 1,000-pound bell was installed at the base of the tower in 1903. In the following year, 200 tons of riprap stones were piled around the outer end of the breakwater to afford more protection for the lighthouse.

William Tarlton Holbrook, keeper from 1910 to 1919, lived in the dwelling with his wife, Evelyn, along with their son, Elias, his wife, Florence, and their daughter, Grace. Elias Holbrook commuted via rowboat to a job at a lobster company on Portland’s Custom House Wharf.

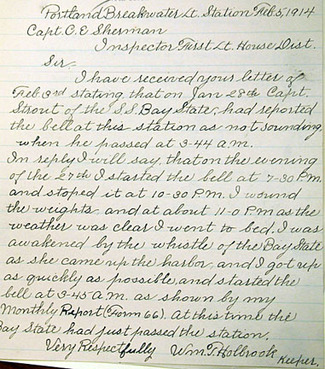

Correspondence from February 1914 illustrates a problem with of light stations with only one keeper—the keeper couldn't be awake all the time. A letter (right) to William Holbrook from the district inspector indicated that a complaint had been received from the captain of the steamer Bay State that the station’s fog bell had not been sounding at 3:44 a.m. during a recent thick fog.

William Tarlton Holbrook, keeper from 1910 to 1919, lived in the dwelling with his wife, Evelyn, along with their son, Elias, his wife, Florence, and their daughter, Grace. Elias Holbrook commuted via rowboat to a job at a lobster company on Portland’s Custom House Wharf.

Correspondence from February 1914 illustrates a problem with of light stations with only one keeper—the keeper couldn't be awake all the time. A letter (right) to William Holbrook from the district inspector indicated that a complaint had been received from the captain of the steamer Bay State that the station’s fog bell had not been sounding at 3:44 a.m. during a recent thick fog.

Holbrook replied that he had sounded the bell from 7:30 to 10:30 p.m. The weather was clear at 11:00 p.m., and he went to bed.

Left: The extended Holbrook family at the lighthouse. Courtesy of the South Portland Historical Society.

He was awakened by a whistle blast from the Bay State, and he had the bell sounding again by 3:45 a.m., one minute after the time of the complaint.

The inspector, showing no sympathy, wrote back, “This office regrets that such reports are received, and you are cautioned to make every effort in the future to have the fog signal at your station in operation during foggy weather.”

He was awakened by a whistle blast from the Bay State, and he had the bell sounding again by 3:45 a.m., one minute after the time of the complaint.

The inspector, showing no sympathy, wrote back, “This office regrets that such reports are received, and you are cautioned to make every effort in the future to have the fog signal at your station in operation during foggy weather.”

Two more children were born to Florence and Elias Holbrook at the lighthouse: William (Bill) in 1911 and Raymond (Ray) in 1913.

National Archives

Many of Ray Holbrook’s memories are recorded in a memoir in the collection of the South Portland Historical Society.

Ray described the dwelling: a kitchen, a dining room, and one bedroom downstairs, and two bedrooms upstairs. Outside the dining room window it was a sheer drop of around 15 feet to the water. Sometimes the window would break in storms, letting and the wind and rain swept inside. The only heat in the house was from a stove in the kitchen, and in the winter the boys would dress and undress next to the stove. There was no electricity and no telephone.

Next to the keeper’s house were a storage shed and, a cistern building, and a two-seater outhouse connected to a shaft leading to the harbor below. “A draft of wind blew up through the shaft blew up through the shaft at high tide,” Raymond recalled. “We were very careful to check the wind and tide before going out there!”

Young Bill and Ray played on a wooden platform outside the dwelling. A favorite pastime was throwing things into the water and watching them float away, but that wasn’t so much fun for Ray when Bill threw his prized teddy bear overboard. During World War I, Ray and Bill marched and drilled on the platform with wooden guns, drums, and flags.

Ray described the dwelling: a kitchen, a dining room, and one bedroom downstairs, and two bedrooms upstairs. Outside the dining room window it was a sheer drop of around 15 feet to the water. Sometimes the window would break in storms, letting and the wind and rain swept inside. The only heat in the house was from a stove in the kitchen, and in the winter the boys would dress and undress next to the stove. There was no electricity and no telephone.

Next to the keeper’s house were a storage shed and, a cistern building, and a two-seater outhouse connected to a shaft leading to the harbor below. “A draft of wind blew up through the shaft blew up through the shaft at high tide,” Raymond recalled. “We were very careful to check the wind and tide before going out there!”

Young Bill and Ray played on a wooden platform outside the dwelling. A favorite pastime was throwing things into the water and watching them float away, but that wasn’t so much fun for Ray when Bill threw his prized teddy bear overboard. During World War I, Ray and Bill marched and drilled on the platform with wooden guns, drums, and flags.

The family was often isolated during icy periods in winter, and sometimes horse-drawn sleighs could be seen traveling over the ice to some of the nearby islands.

Circa late 1800s. (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

If any family members were on shore and couldn’t return because of the weather, they stayed at a friend’s house. Ray started school during the last year the family lived at the lighthouse, but he had to repeat the first grade because he missed so many days when it was impossible to get to the school.

One of Ray Holbrook’s last memories of the lighthouse was November 11, 1918, when whistles blew from every boat and factory in the area at 11:00 a.m. to celebrate the end of World War I.

The light was electrified in 1934, and the job of tending the station went to the keeper at Spring Point Ledge. The last keeper at Portland Breakwater was Preston L. Marr, the son and grandson of keepers at Hendricks Head Light.

The keeper’s house on the breakwater was demolished in late February 1935. In the early 1940s, shipyards expanded into the harbor, shortening the breakwater until the lighthouse stood only 100 feet from the shore.

One of Ray Holbrook’s last memories of the lighthouse was November 11, 1918, when whistles blew from every boat and factory in the area at 11:00 a.m. to celebrate the end of World War I.

The light was electrified in 1934, and the job of tending the station went to the keeper at Spring Point Ledge. The last keeper at Portland Breakwater was Preston L. Marr, the son and grandson of keepers at Hendricks Head Light.

The keeper’s house on the breakwater was demolished in late February 1935. In the early 1940s, shipyards expanded into the harbor, shortening the breakwater until the lighthouse stood only 100 feet from the shore.

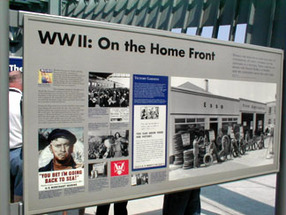

Portland Breakwater Light was darkened in 1942, like many lighthouses during World War II.

U.S. Coast Guard

The fog bell was operated electrically for a while, but the electrical cable was badly damaged by dredging operations. It was subsequently decided, in May 1943, that the light and fog signal were no longer needed for local navigation.

The lighthouse was declared surplus property and was sold into private hands. For some years, the Greater Portland Public Development Commission owned the lighthouse and adjacent land, and the General Electric Company leased the property and maintained a facility nearby.

In 1985, Al Glickman of Spring Point Associates donated the property to the City of South Portland. The South Portland–/Cape Elizabeth Rotary Club spearheaded a 1989 renovation of the lighthouse that included structural repairs and a new coat of paint.

A park has been established adjacent to the lighthouse, officially named “Bug Light Park.” A Liberty Ship memorial in the park, sponsored by the Portland Harbor Museum, was dedicated in November 2001. A total of 274 ships were built on the site during World War II. Most of them were Liberty Ships, which played an important role carrying supplies across the Atlantic during the war. Interpretive signs at the memorial tell the story of the ships built in South Portland.

The lighthouse was declared surplus property and was sold into private hands. For some years, the Greater Portland Public Development Commission owned the lighthouse and adjacent land, and the General Electric Company leased the property and maintained a facility nearby.

In 1985, Al Glickman of Spring Point Associates donated the property to the City of South Portland. The South Portland–/Cape Elizabeth Rotary Club spearheaded a 1989 renovation of the lighthouse that included structural repairs and a new coat of paint.

A park has been established adjacent to the lighthouse, officially named “Bug Light Park.” A Liberty Ship memorial in the park, sponsored by the Portland Harbor Museum, was dedicated in November 2001. A total of 274 ships were built on the site during World War II. Most of them were Liberty Ships, which played an important role carrying supplies across the Atlantic during the war. Interpretive signs at the memorial tell the story of the ships built in South Portland.

Through the 1990s, the tower's condition deteriorated and the ventilator ball was stolen from the top of the lantern. The South Portland/Cape Elizabeth Rotary Club and the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust completed a new restoration culminating in a relighting ceremony on August 14, 2002.

A replacement ventilator ball was installed, donated by the U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team South Portland. The tower was painted inside and out, and a 250 mm optic was added. South Portland Mayor William Dale declared at the relighting ceremony, "This harbor is alive and well, and this lighthouse is representative of it."

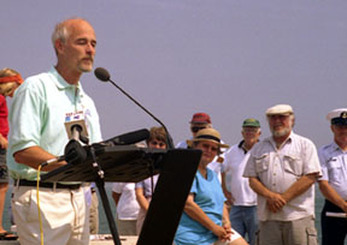

Jack Roberts (left), president of the South Portland-Cape Elizabeth Rotary Club and chairman of the town council of neighboring Cape Elizabeth, added:

Bug Light has a new lease on life. It will shine as the crown jewel of Bug Light Park. . . This lighthouse is so much more than stone and iron. It is living history This lighthouse has stood the test of time for 127 years. With loving care it will be here for another century and beyond.

In the video below, Jack Roberts talks about the lighthouse.

Jack Roberts (left), president of the South Portland-Cape Elizabeth Rotary Club and chairman of the town council of neighboring Cape Elizabeth, added:

Bug Light has a new lease on life. It will shine as the crown jewel of Bug Light Park. . . This lighthouse is so much more than stone and iron. It is living history This lighthouse has stood the test of time for 127 years. With loving care it will be here for another century and beyond.

In the video below, Jack Roberts talks about the lighthouse.

Senior Chief Tommy Dutton of U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team South Portland had the honor of turning on the light at the event.

Left: Many people in attendance at the recommissioning toured the lighthouse.

Portland Breakwater Light's 250 mm optic now exhibits a white flash every four seconds, welcoming visitors to South Portland and historic Portland Harbor.

The lighthouse's concrete foundation was repaired in 2010, and the lighthouse was repainted in 2011. Decorative details on the tower were restored in 2017.

To reach Bug Light Park, follow Broadway in South Portland to its northern end. When you reach the stop sign in front of the Spring Point Marina, turn left. Turn right onto Madison Street and follow it into Bug Light Park. Bear right to the free parking along the water, near the lighthouse.

You can also see the unusual little lighthouse from many excursion boats out of Portland Harbor.

Portland Breakwater Light's 250 mm optic now exhibits a white flash every four seconds, welcoming visitors to South Portland and historic Portland Harbor.

The lighthouse's concrete foundation was repaired in 2010, and the lighthouse was repainted in 2011. Decorative details on the tower were restored in 2017.

To reach Bug Light Park, follow Broadway in South Portland to its northern end. When you reach the stop sign in front of the Spring Point Marina, turn left. Turn right onto Madison Street and follow it into Bug Light Park. Bear right to the free parking along the water, near the lighthouse.

You can also see the unusual little lighthouse from many excursion boats out of Portland Harbor.

Keepers: The following list of keepers is a work in progress. Additional information is welcomed and appreciated; you can email me at [email protected]. If you copy this list to another site, you do so at your own risk. I can't guarantee its accuracy.

W.A. Dyer (1855-1857); William L. Willard (1857-1860); Benjamin F. Willard (1860-1861); Benjamin B. Walton (1861-1866); Len Strout (1866-1867); Paul McKenna (McKenney ?) (1867-1875); Stephen Hubbard (1875-1887); Albus R. Angell (1887-1900); Parker O. Haley (1900 -1908); William T. Holbrook (July 1908 - November 1908); Parker O. Haley (1908 -1909); William T. Holbrook (1909-1919); Preston Marr (?-1934)