History of Bishop and Clerks Lighthouse, near Yarmouth, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Point Gammon and the offshore ledges known as Bishop (largest of the ledges) and Clerks (smaller rocks) were, for many years, scourges to mariners traveling near Hyannis along the south coast of Cape Cod—one writer dubbed them the “Scylla and Charybdis” of Nantucket Sound. The lighthouse established at Point Gammon in 1816 was a help, but it wasn’t sufficient to prevent vessels from running into the treacherous Bishop and Clerks ledges a mile or so offshore.

U.S. Coast Guard

One of the prominent wrecks in the vicinity was the ship Columbus in April 1851. The vessel, bound for Boston with a cargo of salt, struck at Bishop and Clerks and ran ashore at Cotuit. The crew escaped safely, but the ship was badly damaged.

A day beacon marked the spot for some years, before the Lighthouse Board announced in 1855 that a lightship had been built at the navy yard in Boston to be placed at Bishop and Clerks. It wasn’t long before the lightship was deemed insufficient. On August 18, 1856, Congress appropriated $20,000 for a lighthouse at the location.

The building of the lighthouse was a difficult process, similar to the construction of other wave-swept stone towers like Massachusetts' Minot's Ledge Light and England's Eddystone Light. The work began in the spring of 1857. The massive granite blocks were cut onshore and ferried to the site, where they were pieced together on a cylindrical base.

The Lighthouse Board announced that the stonework had almost been completed in 1857, but the 65-foot tower wasn’t finished until the following year.

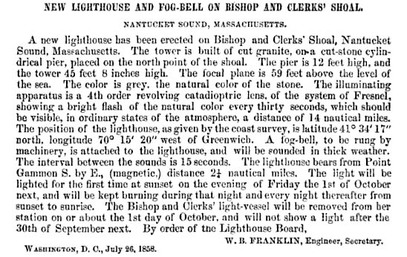

The light went into operation on October 1, 1858. Point Gammon Light was extinguished when the new lighthouse went into service. The lighthouse received a fourth-order Fresnel lens, exhibiting a white flash every 30 seconds from a point 56 feet above the water. The lighthouse also had an automatic fog bell, operated by a clockwork mechanism. The striking machinery and associated weights were housed in a wooden addition to the side of the lighthouse.

A day beacon marked the spot for some years, before the Lighthouse Board announced in 1855 that a lightship had been built at the navy yard in Boston to be placed at Bishop and Clerks. It wasn’t long before the lightship was deemed insufficient. On August 18, 1856, Congress appropriated $20,000 for a lighthouse at the location.

The building of the lighthouse was a difficult process, similar to the construction of other wave-swept stone towers like Massachusetts' Minot's Ledge Light and England's Eddystone Light. The work began in the spring of 1857. The massive granite blocks were cut onshore and ferried to the site, where they were pieced together on a cylindrical base.

The Lighthouse Board announced that the stonework had almost been completed in 1857, but the 65-foot tower wasn’t finished until the following year.

The light went into operation on October 1, 1858. Point Gammon Light was extinguished when the new lighthouse went into service. The lighthouse received a fourth-order Fresnel lens, exhibiting a white flash every 30 seconds from a point 56 feet above the water. The lighthouse also had an automatic fog bell, operated by a clockwork mechanism. The striking machinery and associated weights were housed in a wooden addition to the side of the lighthouse.

A principal keeper and two assistants (usually only two men would be on duty at the lighthouse at the same time) lived inside the tower, which had a kitchen and two bedrooms.

The first principal keeper was John Peak of Hyannis. His father, Samuel Peak, had been keeper of the Point Gammon Light from the time it was built in 1816 until his death in 1824. John took over and remained keeper at Point Gammon until the new tower was completed at Bishop and Clerks.

Some sources claim that John Peak remained keeper until his death in 1886, but payroll records indicate that W. W. Baker took over as principal keeper in 1859. Turnover was frequent, as was common at isolated offshore lights. At least 35 men served at the lighthouse in its 65 years as a staffed station.

Captain Charles H. Hinckley, a native of Barnstable, was an assistant keeper from 1881 to 1884. He left for a few years at Dumpling Rock Light, but returned as prinicipal keeper at Bishop and Clerks in 1892. His wife, Dorinda (Bearse), sometimes visited the lighthouse to stay with her husband.

Some sources claim that John Peak remained keeper until his death in 1886, but payroll records indicate that W. W. Baker took over as principal keeper in 1859. Turnover was frequent, as was common at isolated offshore lights. At least 35 men served at the lighthouse in its 65 years as a staffed station.

Captain Charles H. Hinckley, a native of Barnstable, was an assistant keeper from 1881 to 1884. He left for a few years at Dumpling Rock Light, but returned as prinicipal keeper at Bishop and Clerks in 1892. His wife, Dorinda (Bearse), sometimes visited the lighthouse to stay with her husband.

Hinckley remained at the lighthouse until 1919, when he was 70. Hinckley, who was 4 feet 9 inches (or 4 feet 6 inches in his stocking feet, according to one account), has been called the shortest lighthouse keeper in the world.

Hinckley, whose father was a prominent Cape Cod doctor, had gone to sea at the age of 16 as a cabin boy on an East Indies-bound ship. He said the first and most important thing he learned about seafaring life was “to move when spoken to, to jump quickly to one side and avoid the real attack that was sure to come.” He “knocked about” in a variety of vessels for 15 years before becoming a lighthouse keeper.

Right: Keeper Charles Hinckley (4'9") with local ferry captain Walter Carney (6'7") of Hyannisport. Hinckley referred to himself and Carney as the "long and short of the service."

Hinckley was interviewed by the Boston Herald in 1907. Here's an excerpt:

In 1892 I became Captain of Bishop and Clerks. This is one of the most important lights on Cape Cod, as it commands both the north and south channels and is of assistance to vessels coming up over the shoals around Monomoy Point.

It requires lots of philosophy to be a light-keeper on an outside station. At Bishop and Clerks, for example, the keeper has twenty days on and ten days off. The past two years has [sic] been the best that has ever been known. Only twice during the winter periods, have conditions been such that we could not get ashore. In the year 1903, for 48 days the sound was full of ice and at times it was piled around the light to the height of twenty feet.

Right: Keeper Charles Hinckley (4'9") with local ferry captain Walter Carney (6'7") of Hyannisport. Hinckley referred to himself and Carney as the "long and short of the service."

Hinckley was interviewed by the Boston Herald in 1907. Here's an excerpt:

In 1892 I became Captain of Bishop and Clerks. This is one of the most important lights on Cape Cod, as it commands both the north and south channels and is of assistance to vessels coming up over the shoals around Monomoy Point.

It requires lots of philosophy to be a light-keeper on an outside station. At Bishop and Clerks, for example, the keeper has twenty days on and ten days off. The past two years has [sic] been the best that has ever been known. Only twice during the winter periods, have conditions been such that we could not get ashore. In the year 1903, for 48 days the sound was full of ice and at times it was piled around the light to the height of twenty feet.

In 1909, the magazine Along the Coast quoted Hinckley:

There ain't a great deal of me so far as height goes but I am all right from my feet up. I've laid many a man bigger than me on his back if I do say it myself.

Betty Bugbee Cusack, in her book Collector's Luck: A Thousand Years at Lewis Bay, Cape Cod, remembered her friend, Mrs. Cook of Hyannis, who often visited the lighthouse as a girl. Mrs. Cook was the niece of Keeper Hinckley. Mrs. Cook said she could “just smell the cornbread and those boiling lobsters now, thinking about those trips.”

Cusack also wrote the Hinckley was a familiar sight in Hyannis after his lighthouse keeping days: “He was always busy, either digging and selling a few clams, doing an odd job here and there, or tending somebody's furnace . . . doing it all with a cheerful optimism.”

A 1929 newspaper article reported that Hinckley was in charge of keeping the furnace fires burning in the Hyannis Public Library and some other buildings. According to the article, "The lonesome experiences [of lighthouse keeping] have not left the spirit dark for his merry salutations and bits of humorous conversation are akin to light."

Father of four and a lighthouse keeper for 38 years, Charles Hinckley died in 1932. His son, Charles, Jr., later served as the Hyannis harbormaster.

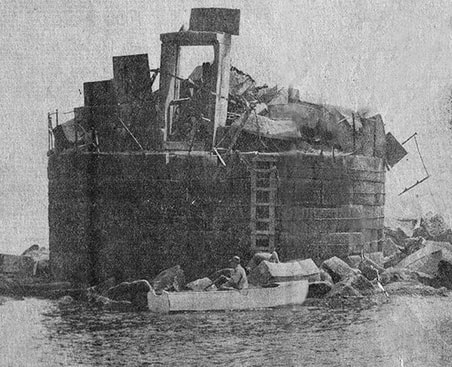

The lighthouse was converted to automatic acetylene gas operation in 1923 and discontinued in 1928. It continued to serve as a day beacon, but suffered from the sea's battering as well as vandalism. A storm in 1935 did considerable damage.

Cusack also wrote the Hinckley was a familiar sight in Hyannis after his lighthouse keeping days: “He was always busy, either digging and selling a few clams, doing an odd job here and there, or tending somebody's furnace . . . doing it all with a cheerful optimism.”

A 1929 newspaper article reported that Hinckley was in charge of keeping the furnace fires burning in the Hyannis Public Library and some other buildings. According to the article, "The lonesome experiences [of lighthouse keeping] have not left the spirit dark for his merry salutations and bits of humorous conversation are akin to light."

Father of four and a lighthouse keeper for 38 years, Charles Hinckley died in 1932. His son, Charles, Jr., later served as the Hyannis harbormaster.

The lighthouse was converted to automatic acetylene gas operation in 1923 and discontinued in 1928. It continued to serve as a day beacon, but suffered from the sea's battering as well as vandalism. A storm in 1935 did considerable damage.

By 1952, the tower tilted to one side and was missing many blocks.

The Coast Guard decided to raze the structure. Hired to carry out the demolition was the McKie Lighter Company and U. O. MacDonald of Boston, a blasting expert.

Preparations took a week. Dynamite was placed strategically in drilled holes in such a way to direct the blast upward, so the debris wouldn’t scatter over too large an area. It was hoped that some of the materials could be salvaged.

As hundreds of people in pleasure craft watched on September 11, 1952, the tugboat Irene and Mary flew a red flag of warning. When the proper time came—12:57 p.m.—the tug blew six blasts on its whistle.

Preparations took a week. Dynamite was placed strategically in drilled holes in such a way to direct the blast upward, so the debris wouldn’t scatter over too large an area. It was hoped that some of the materials could be salvaged.

As hundreds of people in pleasure craft watched on September 11, 1952, the tugboat Irene and Mary flew a red flag of warning. When the proper time came—12:57 p.m.—the tug blew six blasts on its whistle.

The Boston Globe described the spectacle:

A cloud of smoke partly hid the old tower, which stood swaying for a moment and then toppled to one side like a pile of child's blocks... The historic Bishop and Clerks Lighthouse was no more.

For many years a 30-foot pyramidal day beacon marked the spot where the lighthouse once stood. There is now a small lighted tower on the spot.

In addition, several buoys warn mariners away from the dangerous shoals that were guarded by Bishop and Clerks Light for nearly a century.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Peak (1858-1859); W. W. Baker (1859-1860); D. Taylor (1860-1861); V. (?) Harding (1861-1866); George L. Lewis (1866-1873); Charles F. Swain (1873-1886); Franklin Percival (1886-1887); George A. Smith (1890-1891); Charles Hinckley (1892-1919)

Assistants: H. Crowell (1859); John Bates (1859); B. Baxter (1859); Nathan Baxter (1859-1860); William Robbins (1860-1861); Amos Crowell (1861-1871); Lawrence Chase (1867); Lovell Lewis (1867-1869); John Peak (1869); Joseph P. Bearse (1871-1883); Elisha Loring (1874-1879); William Ramsdell (1879-1880); Samuel Adams Peak, 2nd assistant (1880-1881); Joel Hamblin (1881); Marcus B. Baker (2nd assistant, 1883-1884); Franklin Percival (2nd assistant, 1884, 1st assistant 1884-1886); William A. Dixon (2nd assistant 1884-1885); Amos F. Howes (?) (2nd assistant, 1885-1886); George A. Smith (2nd assistant 1886, 1st assistant 1886-1890); Benjamin B. Baxter (2nd assistant 1886-1891, 1st assistant 1891-1896); Joseph H. Bearse (2nd assistant, 1891-1892); Charles Hinckley (2nd assistant 1881-1883, 1st assistant 1883-1884); Halvor (?) M. Jansen (1st assistant, 1892-1898); William A. Howland (1st assistant, 1898-); Winfield S. S. Hooper (2nd assistant, 1903-); Joshua A. Montcalm (2nd assistant 1903-c. 1908)

John Peak (1858-1859); W. W. Baker (1859-1860); D. Taylor (1860-1861); V. (?) Harding (1861-1866); George L. Lewis (1866-1873); Charles F. Swain (1873-1886); Franklin Percival (1886-1887); George A. Smith (1890-1891); Charles Hinckley (1892-1919)

Assistants: H. Crowell (1859); John Bates (1859); B. Baxter (1859); Nathan Baxter (1859-1860); William Robbins (1860-1861); Amos Crowell (1861-1871); Lawrence Chase (1867); Lovell Lewis (1867-1869); John Peak (1869); Joseph P. Bearse (1871-1883); Elisha Loring (1874-1879); William Ramsdell (1879-1880); Samuel Adams Peak, 2nd assistant (1880-1881); Joel Hamblin (1881); Marcus B. Baker (2nd assistant, 1883-1884); Franklin Percival (2nd assistant, 1884, 1st assistant 1884-1886); William A. Dixon (2nd assistant 1884-1885); Amos F. Howes (?) (2nd assistant, 1885-1886); George A. Smith (2nd assistant 1886, 1st assistant 1886-1890); Benjamin B. Baxter (2nd assistant 1886-1891, 1st assistant 1891-1896); Joseph H. Bearse (2nd assistant, 1891-1892); Charles Hinckley (2nd assistant 1881-1883, 1st assistant 1883-1884); Halvor (?) M. Jansen (1st assistant, 1892-1898); William A. Howland (1st assistant, 1898-); Winfield S. S. Hooper (2nd assistant, 1903-); Joshua A. Montcalm (2nd assistant 1903-c. 1908)