History of Scituate Light, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Members of the Plymouth Colony, along with newcomers from England, settled the area we now know as Scituate, on Boston's South Shore, in 1627. Its name comes from an Indian word for "cold brook," and refers to a brook that runs into the harbor.

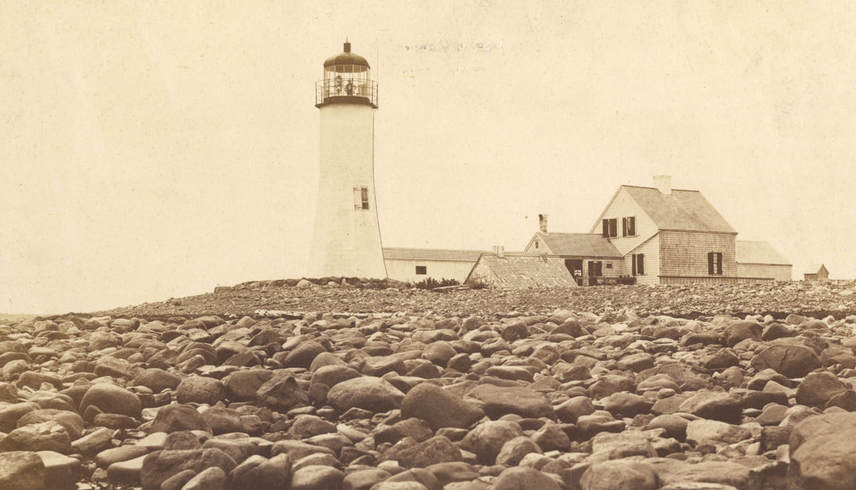

Circa 1859. (National Archives)

The town developed a significant fishing industry by the late eighteenth century, owing to its small but protected harbor, sheltered by Cedar Point to the north and First Cliff to the south. Entering the harbor was difficult because of shallow water and mud flats.

Local citizens petitioned the town's selectmen for a lighthouse in 1807. The selectmen convinced the federal government to appropriate $4,000 in 1810 for the building of a lighthouse at the harbor entrance at Cedar Point.

Three men from the nearby town of Hingham built the lighthouse, finishing it in September 1811, two months ahead of schedule. The 25-foot-tall stone tower was accompanied by a one-and-a-half-story keeper's house, an oil vault, and a well.

The Boston Marine Society was concerned that the new light be easy to differentiate from other lights in Boston Bay. In October 1811, a committee of the society met to discuss the situation with the local lighthouse superintendent. They asked that the light not be put into service until the following March, after sufficient discussion of its characteristic. The society recommended that an eclipser be installed to create a flashing light. Instead, Scituate Light went into service as a fixed white light in April 1812.

The first keeper was Simeon Bates, who stayed at the station until his death in 1834. Bates and his wife, Rachel, had nine children, including two daughters, Rebecca and Abigail. These two sisters would become heroic figures in the history of American lighthouses.

During the War of 1812, British warships frequently raided New England coastal towns. On June 11, 1814, British forces plundered and burned a number of vessels at Scituate. Keeper Bates fired two shots from a small cannon, angering the captain of a British warship as it departed.

Local citizens petitioned the town's selectmen for a lighthouse in 1807. The selectmen convinced the federal government to appropriate $4,000 in 1810 for the building of a lighthouse at the harbor entrance at Cedar Point.

Three men from the nearby town of Hingham built the lighthouse, finishing it in September 1811, two months ahead of schedule. The 25-foot-tall stone tower was accompanied by a one-and-a-half-story keeper's house, an oil vault, and a well.

The Boston Marine Society was concerned that the new light be easy to differentiate from other lights in Boston Bay. In October 1811, a committee of the society met to discuss the situation with the local lighthouse superintendent. They asked that the light not be put into service until the following March, after sufficient discussion of its characteristic. The society recommended that an eclipser be installed to create a flashing light. Instead, Scituate Light went into service as a fixed white light in April 1812.

The first keeper was Simeon Bates, who stayed at the station until his death in 1834. Bates and his wife, Rachel, had nine children, including two daughters, Rebecca and Abigail. These two sisters would become heroic figures in the history of American lighthouses.

During the War of 1812, British warships frequently raided New England coastal towns. On June 11, 1814, British forces plundered and burned a number of vessels at Scituate. Keeper Bates fired two shots from a small cannon, angering the captain of a British warship as it departed.

The children's book Sisters of Scituate Light (left) is based on a true story.

Less than three months later, Keeper Bates and most of his family were away, leaving 21-year-old Rebecca and 15-year-old (or, according to some accounts, 17-year-old) Abigail in charge. The sisters were horrified to see a British warship anchored in the harbor. In a magazine article many years later, Rebecca was quoted:

"I'll tell you what I'll do," says I to my sister, "Look here, you take the drum and I'll take the fife." I was fond of military music and could play four tunes on the fife -- Yankee Doodle was my masterpiece. . . . "What good'll that do?" says she. "Scare them," says I. "All you've got to do is call the roll. I'll scream the fife and we must keep out of sight; if they see us they'll laugh us to scorn."

Less than three months later, Keeper Bates and most of his family were away, leaving 21-year-old Rebecca and 15-year-old (or, according to some accounts, 17-year-old) Abigail in charge. The sisters were horrified to see a British warship anchored in the harbor. In a magazine article many years later, Rebecca was quoted:

"I'll tell you what I'll do," says I to my sister, "Look here, you take the drum and I'll take the fife." I was fond of military music and could play four tunes on the fife -- Yankee Doodle was my masterpiece. . . . "What good'll that do?" says she. "Scare them," says I. "All you've got to do is call the roll. I'll scream the fife and we must keep out of sight; if they see us they'll laugh us to scorn."

The British thought the sound of the fife and drum signaled the approach of the Scituate town militia, and they hastily retreated. Thus was born the legend of Scituate's "Lighthouse Army of Two."

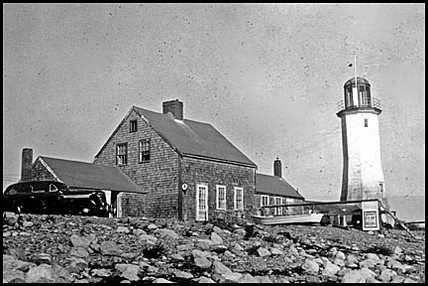

Around 1900 (National Archives)

The Bates sisters lived to be quite elderly. Rebecca later sold affidavits for ten cents apiece, always asserting the truth of her story in spite of doubters. David Ball of the Scituate Historical Society has done extensive research into the story and believes it is likely true.

In 1827, a 15-foot brick extension and a new lantern were added to the lighthouse in order to increase its visibility. When the work was completed, a fixed white light was displayed from the lantern, while a red light was shown from the lower windows. Eight lamps and reflectors produced the red light, while seven lamps and reflectors produced the white light.

In 1827, a 15-foot brick extension and a new lantern were added to the lighthouse in order to increase its visibility. When the work was completed, a fixed white light was displayed from the lantern, while a red light was shown from the lower windows. Eight lamps and reflectors produced the red light, while seven lamps and reflectors produced the white light.

The white-over-red configuration was designed to allow mariners to differentiate Scituate Light from Boston Light a few miles up the coast, but the white and red lights tended to merge from a distance, and for some years vessels continued to crash into the dangerous ledges offshore. New lighting apparatus and a new lantern were installed under the direction of Winslow Lewis in 1841.

The breakwater near the lighthouse

In 1842, Keeper Ebenezer Osborne complained that the tower leaked and that all the woodwork was rotten, and that the dwelling was a "miserable, leaky, smoky, and uncomfortable tenement." Engineer I.W.P. Lewis reported that the interior of the tower was covered with ice in the winter and mold in the summer and said, "A new dwelling-house is very much needed here."

Minor improvements were made, but the government held off on the construction of a new tower. They had a new lighthouse in mind, not at Cedar Point, but offshore at Minot's Ledge. Construction on the first Minot's Ledge Lighthouse began in 1847, and the tower was first lit on January 1, 1850. Scituate Light remained in service, with a fixed red light. The tower at Minot's Ledge was destroyed in a storm on April 16, 1851, and the light at Cedar Point regained a measure of importance.

The lighthouse received a new Fresnel lens in 1855. Then, when the second Minot's Ledge Light was lighted on November 15, 1860, Scituate Light went dark on the same night, seemingly forever.

The federal government had a 630-foot breakwater built at Cedar Point between 1885 and 1890, which made the harbor into a more secure place of refuge. Years later, a second 450-foot jetty was added, extending southwest from the base of the first jetty. A light was exhibited from a lamp on a spar at the breakwater's end beginning on June 10, 1891. The light was shown from a skeleton tower after the spar was carried away by high seas in early 1904.

Minor improvements were made, but the government held off on the construction of a new tower. They had a new lighthouse in mind, not at Cedar Point, but offshore at Minot's Ledge. Construction on the first Minot's Ledge Lighthouse began in 1847, and the tower was first lit on January 1, 1850. Scituate Light remained in service, with a fixed red light. The tower at Minot's Ledge was destroyed in a storm on April 16, 1851, and the light at Cedar Point regained a measure of importance.

The lighthouse received a new Fresnel lens in 1855. Then, when the second Minot's Ledge Light was lighted on November 15, 1860, Scituate Light went dark on the same night, seemingly forever.

The federal government had a 630-foot breakwater built at Cedar Point between 1885 and 1890, which made the harbor into a more secure place of refuge. Years later, a second 450-foot jetty was added, extending southwest from the base of the first jetty. A light was exhibited from a lamp on a spar at the breakwater's end beginning on June 10, 1891. The light was shown from a skeleton tower after the spar was carried away by high seas in early 1904.

Keepers were assigned to the jetty light and lived in the old Scituate Light keeper's house. In 1924, a new acetylene automatic light was installed, and a keeper was no longer needed.

The lighthouse tower, which had its lantern removed, had been long abandoned. The local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution launched a petition drive to restore the tower in 1907 and presented the petition, with 600 signatures, to their representative in Congress.

It appears no action was taken until 1912, when Selectman Jamie Turner and his wife, Jessie, learned that the property was to be auctioned the very next day. Jessie Turner took a train to Boston with a $1,000 check from the town's treasurer. Her efforts put a hold on the auction proceedings.

Scituate residents appealed to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and the sale was delayed. Among those who eventually contributed to the purchase price of $4,000 was William Bates, grandnephew of Abigail and Rebecca Bates. The sale to the town of Scituate became official in 1917.

It appears no action was taken until 1912, when Selectman Jamie Turner and his wife, Jessie, learned that the property was to be auctioned the very next day. Jessie Turner took a train to Boston with a $1,000 check from the town's treasurer. Her efforts put a hold on the auction proceedings.

Scituate residents appealed to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and the sale was delayed. Among those who eventually contributed to the purchase price of $4,000 was William Bates, grandnephew of Abigail and Rebecca Bates. The sale to the town of Scituate became official in 1917.

The town had a replica lantern created and installed in 1930. Some improvements were made to the lighthouse and keeper's house, but by the 1960s the house was again in disrepair.

Circa 1946, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell

In 1968, custody of the site was awarded to the Scituate Historical Society. Today, contributions and rent paid by the residents of the keeper's house pay for the upkeep of the property.

Some people have claimed that the ghosts of Rebecca and Abigail Bates haunt Scituate Light. Fife and drum music, they say, can be heard blending in with the wind and waves.

In a blizzard on March 16, 1956, the Italian freighter Etrusco ran aground near the lighthouse. The Coast Guard rescued the crew by breeches buoy.

The ship remained at Cedar Point until the following December, when it was floated off at high tide after much of the rock around it was blasted away.

Some people have claimed that the ghosts of Rebecca and Abigail Bates haunt Scituate Light. Fife and drum music, they say, can be heard blending in with the wind and waves.

In a blizzard on March 16, 1956, the Italian freighter Etrusco ran aground near the lighthouse. The Coast Guard rescued the crew by breeches buoy.

The ship remained at Cedar Point until the following December, when it was floated off at high tide after much of the rock around it was blasted away.

Many thousands of people visited Scituate Light that year to see the enormous wreck.

The Etrusco aground near the lighthouse in 1956

George and Ruth Downton lived in the keeper's house for many years beginning in 1986. George Downton stepped into the role of modern-day lighthouse keeper, helping to maintain the property and greeting throngs of visitors during Scituate Heritage Days and other events. He also played an active role in the development of the Scituate Maritime and Irish Mossing Museum.

In July 1991, the lighthouse was relighted, with the light visible from land only. A new 27-inch diameter ventilator ball was crafted for the top of the lantern by local resident Herb Jason, using a ball from Sankaty Head Light as a model.

In August 1994, Scituate Light's comeback climaxed when the nation's eleventh oldest lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation. Its white light is visible for four miles. At the relighting ceremony, Kathleen Laidlaw of the Scituate Historical Society said, "The lighthouse has become almost the symbol of Scituate. The light will bring it back to life."

By the early twenty-first century, it was realized that nearly 180 years of harsh New England winters had caused the bricks in the upper portion of the lighthouse tower to deteriorate. In early 2004, spalling of the brick faces was clearly visible from the ground. It was determined that the outer layer of bricks needed to be replaced. ESI Waterproofing and Masonry Restoration, Inc., of Boston, performed the restoration of the tower in 2004. By June 2005, the tower was repainted and was looking as good as -- or better than -- new.

Scituate Light is easy to drive to and there's a large parking lot. Bear in mind that the keeper's house is a private residence. The tower is normally closed to the public, but there are open house dates each year.

In early 2009, schoolteacher Bob Gallagher was chosen by the Scituate Historical Society to be the new resident caretaker. You can follow his adventures on his blog site.

Listen to "Light Hearted," the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, episode 190, about Scituate Lighthouse.

In July 1991, the lighthouse was relighted, with the light visible from land only. A new 27-inch diameter ventilator ball was crafted for the top of the lantern by local resident Herb Jason, using a ball from Sankaty Head Light as a model.

In August 1994, Scituate Light's comeback climaxed when the nation's eleventh oldest lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation. Its white light is visible for four miles. At the relighting ceremony, Kathleen Laidlaw of the Scituate Historical Society said, "The lighthouse has become almost the symbol of Scituate. The light will bring it back to life."

By the early twenty-first century, it was realized that nearly 180 years of harsh New England winters had caused the bricks in the upper portion of the lighthouse tower to deteriorate. In early 2004, spalling of the brick faces was clearly visible from the ground. It was determined that the outer layer of bricks needed to be replaced. ESI Waterproofing and Masonry Restoration, Inc., of Boston, performed the restoration of the tower in 2004. By June 2005, the tower was repainted and was looking as good as -- or better than -- new.

Scituate Light is easy to drive to and there's a large parking lot. Bear in mind that the keeper's house is a private residence. The tower is normally closed to the public, but there are open house dates each year.

In early 2009, schoolteacher Bob Gallagher was chosen by the Scituate Historical Society to be the new resident caretaker. You can follow his adventures on his blog site.

Listen to "Light Hearted," the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, episode 190, about Scituate Lighthouse.

In the video clip above, the Flying Santa visits Scituate Lighthouse on Dec. 15, 2012.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Simeon Bates (1811-1834); Zeba Cushing (1834-1840); Ebenezer Osborne (1840-1849); James Bates (1849-1851); Anthony Waterman (1851-1853); Alonzo Jones (1853-1856); Thomas Richardson (1856-1860); John Prouty (keeper of light on jetty 1891-1904); John Frank Cushman (keeper of light on jetty 1904-1924); James Arthur Cobbett (caretaker, 1936-1947); Robert F. Abell (caretaker, 1971-1973); Elizabeth Foster (caretaker, 1973-1988); George Downton (caretaker 1988-2000); Bob Gallagher (caretaker 2009-)

Simeon Bates (1811-1834); Zeba Cushing (1834-1840); Ebenezer Osborne (1840-1849); James Bates (1849-1851); Anthony Waterman (1851-1853); Alonzo Jones (1853-1856); Thomas Richardson (1856-1860); John Prouty (keeper of light on jetty 1891-1904); John Frank Cushman (keeper of light on jetty 1904-1924); James Arthur Cobbett (caretaker, 1936-1947); Robert F. Abell (caretaker, 1971-1973); Elizabeth Foster (caretaker, 1973-1988); George Downton (caretaker 1988-2000); Bob Gallagher (caretaker 2009-)