History of Bear Island Light, Northeast Harbor, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Northeast Harbor is a sequestered nook, rising to wooded heights, in which one imagines no end of sylvan retreats. The air grows warmer, and is heavy with the fragrance of the pines... The eastern channel into the sound is between Sutton's and Bear Island (lighthouse)... All the Cranberry Islands are inhabited and have growing summer colonies... They owe their rise to fishing, and their name to a cranberry bog of two hundred acres. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

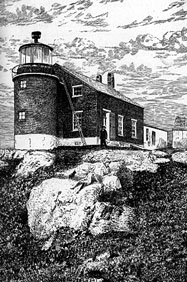

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Eleven-acre Bear Island, near the town of Northeast Harbor on Mount Desert Island, is one of the island group known as the Cranberry Isles. Nineteenth-century landscape artists, including Frederick Church and Albert Bierstadt, were drawn to Bear Island’s rugged beauty.

The historian Charles B. McLane postulated that the island’s name was originally “Bare.” McLane believed that the name stemmed from the island’s treeless appearance from the west rather than the unlikely presence of bears.Baker Island Light, the first lighthouse in the Mount Desert Island region, had been established in 1828. A naval captain wrote that the area between the southern shore of Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles was a “general rendezvous for coasting vessels and fishermen in bad weather” and a “focal point for all vessels passing through the in-shore thoroughfare.” Spurling Point on Great Cranberry Island was considered as a lighthouse site, but Bear Island was chosen instead.

The historian Charles B. McLane postulated that the island’s name was originally “Bare.” McLane believed that the name stemmed from the island’s treeless appearance from the west rather than the unlikely presence of bears.Baker Island Light, the first lighthouse in the Mount Desert Island region, had been established in 1828. A naval captain wrote that the area between the southern shore of Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles was a “general rendezvous for coasting vessels and fishermen in bad weather” and a “focal point for all vessels passing through the in-shore thoroughfare.” Spurling Point on Great Cranberry Island was considered as a lighthouse site, but Bear Island was chosen instead.

Congress appropriated $3,000 for the building of a lighthouse on the island in July 1838. William Moore sold two acres of land on the island to the federal government, and the station went into service in 1839.

According to some sources, William Moore became the first keeper. If he did serve in that capacity, his tenure was brief. According to most sources, John G. Bowen (sometimes spelled “Bowan”) was the first keeper. Bear Island was always a family light station with one keeper.

The first lighthouse building took the form of a wooden tower on the southern end of the roof of a small rubblestone dwelling; its seven lamps and 13-inch reflectors in an octagonal wrought-iron lantern showed a fixed white light 98 feet above mean high water. A 10-foot-wide embankment of logs and gravel was formed to the west of the lighthouse for protection.

A newspaper report in March 1842 described a tremendous storm that had battered Bear Island a few weeks earlier “with great violence for twenty hours.” The storm left the dwelling windows, high above the sea, caked with salt spray.

Right: 1880s engraving of Bear Island Light from the book, All Among the Lighthouses.

The first lighthouse building took the form of a wooden tower on the southern end of the roof of a small rubblestone dwelling; its seven lamps and 13-inch reflectors in an octagonal wrought-iron lantern showed a fixed white light 98 feet above mean high water. A 10-foot-wide embankment of logs and gravel was formed to the west of the lighthouse for protection.

A newspaper report in March 1842 described a tremendous storm that had battered Bear Island a few weeks earlier “with great violence for twenty hours.” The storm left the dwelling windows, high above the sea, caked with salt spray.

Right: 1880s engraving of Bear Island Light from the book, All Among the Lighthouses.

There was some discussion of discontinuing Bear Island Light in the early 1840s. The light was retained, in part because of the pleas of a Captain Doyle, who claimed that he would have lost his vessel with a valuable cargo during a voyage from Eastport if it had not been for the light.

Circa 1880

Lighthouse-keeping appointments were highly political in the first half of the nineteenth century. After Bowen was dismissed in 1842, Secretary of the Treasury Walter Forward explained the purported reasons. “Interference in elections, both under the late and present administrations, and absence from the lighthouse for days in succession are the principal charges against Mr. Bowen,” Forward wrote to a Maine congressman in June 1842.

Solomon L. Howes, who became keeper in March 1842, was in charge when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station for his 1843 report to Congress. Lewis found the construction of the buildings “weak and defective.”

John Bowen returned for a second stint as keeper (1844–50). In March 1850, a local politician, Charles Peters, wrote to a justice of the peace in favor of Bowen’s removal: “Washington needs to know what kind of a critter Bowan has been. . . . if he has been known to attend political conventions . . . if he has been an active and brawling Partizan. . . . I want to sluice Bowan before he knows it.” After many prominent Whigs signed a petition, Bowen was removed in favor of Levi Robinson, a native of the nearby town of Tremont.

Solomon L. Howes, who became keeper in March 1842, was in charge when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station for his 1843 report to Congress. Lewis found the construction of the buildings “weak and defective.”

John Bowen returned for a second stint as keeper (1844–50). In March 1850, a local politician, Charles Peters, wrote to a justice of the peace in favor of Bowen’s removal: “Washington needs to know what kind of a critter Bowan has been. . . . if he has been known to attend political conventions . . . if he has been an active and brawling Partizan. . . . I want to sluice Bowan before he knows it.” After many prominent Whigs signed a petition, Bowen was removed in favor of Levi Robinson, a native of the nearby town of Tremont.

A fire did great damage to the lighthouse building in 1852, and the 1854 annual report of the lighthouse board announced that the station had been rebuilt.

From "Stebbins Illustrated Coast Pilot," 1902

The new lighthouse consisted of a round brick tower at one end of the dwelling. It seems likely that much of the original dwelling was salvaged during the 1853 rebuilding.

Around the time of the station’s rebuilding, John G. Bowen returned for a third and final stint as keeper (1853–55). Caleb S. Gould succeeded Bowen in 1855. It isn’t clear how many children Gould had, but there were enough, in combination with one other family on the island, for Bear Island to be named a separate school district under Gould’s direction in 1856. School was taught on the island until 1871, when William Fennelly was keeper. It was resumed for some years beginning in 1880. Stephen Smallidge, keeper at that time, had five children.

A fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in 1856. In 1888, a 1,000-pound fog bell and striking apparatus were installed. Also in 1888, the dwelling was reported to be quite dilapidated.

Around the time of the station’s rebuilding, John G. Bowen returned for a third and final stint as keeper (1853–55). Caleb S. Gould succeeded Bowen in 1855. It isn’t clear how many children Gould had, but there were enough, in combination with one other family on the island, for Bear Island to be named a separate school district under Gould’s direction in 1856. School was taught on the island until 1871, when William Fennelly was keeper. It was resumed for some years beginning in 1880. Stephen Smallidge, keeper at that time, had five children.

A fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in 1856. In 1888, a 1,000-pound fog bell and striking apparatus were installed. Also in 1888, the dwelling was reported to be quite dilapidated.

The present 31-foot brick lighthouse was built in 1889–90 after a congressional appropriation of $3,750, as were a new one-and-one-half-story, wood-frame keeper’s house and a barn.

Elmo J. Turner, courtesy of Joyce MacIlroy

An oil house and boathouse were added later. The Fresnel lens was moved to the new tower, exhibiting its light from 100 feet above the water.

For a time beginning in 1887, Bear Island had a buoy depot where navigational aids were maintained; the depot was later transferred to Southwest Harbor. There was also a coaling station so buoy tenders in the area could refuel.

Elmo J. Turner was the keeper for some years in the 1930s, after time at Great Duck Island Light. Like many lighthouse families, Turner and his wife kept chickens and a cow at the island station.

“There was no power on the island,” says Turner’s great-granddaughter, Joyce MacIlroy, “so my great-grandmother would keep the fresh cream in the cellar.

One day, the cow had to be taken to the mainland, so Elmo loaded her into the dory and rowed her across to Northeast Harbor, then rowed her back over to the island. The cow got seasick on the way back—that must have been quite the sight!”

For a time beginning in 1887, Bear Island had a buoy depot where navigational aids were maintained; the depot was later transferred to Southwest Harbor. There was also a coaling station so buoy tenders in the area could refuel.

Elmo J. Turner was the keeper for some years in the 1930s, after time at Great Duck Island Light. Like many lighthouse families, Turner and his wife kept chickens and a cow at the island station.

“There was no power on the island,” says Turner’s great-granddaughter, Joyce MacIlroy, “so my great-grandmother would keep the fresh cream in the cellar.

One day, the cow had to be taken to the mainland, so Elmo loaded her into the dory and rowed her across to Northeast Harbor, then rowed her back over to the island. The cow got seasick on the way back—that must have been quite the sight!”

Bear Island remained a family light station under the U.S. Coast Guard. In the late 1950s, Terry and Nancy Stanley lived at the lighthouse. In a 1989 interview, Terry Stanley remembered tending the fog bell: “It worked like a Swiss clock. You cranked weights up to the top of the tower and it would ring the bell every so many minutes.”

Stanley enjoyed fishing and lobstering around the island, and he also carved wooden fish and birds. Evenings were spent watching TV or playing cards.

Nancy Stanley recalled the station’s dog, Cleo. “When we took her ashore, she didn’t know what to make of all the cars. Of course, she had only seen boats up until then.”

The station had a huge refrigerator, but the tiny freezer had room for only one ice tray. “We ate an awful lot of macaroni and cheese, tuna casseroles, and Spam,” Nancy laughingly recalled. She made frequent solo runs to Northeast Harbor in a small outboard motorboat to pick up supplies.

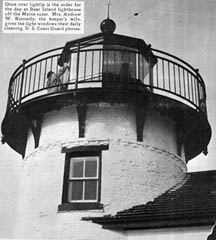

Right: This photo was published in April 1946 with the following caption - "Once over lightly is the order of the day at Bear Island Lighthouse off the Maine coast. Mrs. Andrew W. Kennedy, the keeper's wife, gives the light windows their daily cleaning." U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Nancy Stanley recalled the station’s dog, Cleo. “When we took her ashore, she didn’t know what to make of all the cars. Of course, she had only seen boats up until then.”

The station had a huge refrigerator, but the tiny freezer had room for only one ice tray. “We ate an awful lot of macaroni and cheese, tuna casseroles, and Spam,” Nancy laughingly recalled. She made frequent solo runs to Northeast Harbor in a small outboard motorboat to pick up supplies.

Right: This photo was published in April 1946 with the following caption - "Once over lightly is the order of the day at Bear Island Lighthouse off the Maine coast. Mrs. Andrew W. Kennedy, the keeper's wife, gives the light windows their daily cleaning." U.S. Coast Guard photo.

One of the last Coast Guard keepers at Bear Island was Steve Oliver. "This light hasn't missed a blink since I've been here," Oliver told the Christian Science Monitor.

He voiced his fears regarding automation: "I just hope that in the need to economize we don't destroy the things that give flavor and uniqueness to life."

In the early 1980s, Bear Island Light was discontinued and replaced by an offshore lighted bell buoy.

The property became part of Acadia National Park in 1987. Through most of the 1980s, the station fell into disrepair.

In the early 1980s, Bear Island Light was discontinued and replaced by an offshore lighted bell buoy.

The property became part of Acadia National Park in 1987. Through most of the 1980s, the station fell into disrepair.

In 1989, the Friends of Acadia refurbished the keeper's house for $17,000 and the tower was relighted as a private aid to navigation.

Circa late 1980s

The National Park Service then granted a long-term lease on the property to Martin Morad, who is required to pay for the upkeep of the property.

Morad, originally from Iran, is a professor of pharmacology and medicine at Georgetown University. Fabiola Martens, his wife, is Belgian. She is a former lawyer and now is an interior designer. Morad had originally seen Bear Island Lighthouse in 1971 and had attempted to buy or lease it to no avail. By 1989, the house had fallen into such poor condition that it took three years of renovation before Morad and Martens could move in.

Bear Island Light is best viewed by boat; click here for more information.

Morad, originally from Iran, is a professor of pharmacology and medicine at Georgetown University. Fabiola Martens, his wife, is Belgian. She is a former lawyer and now is an interior designer. Morad had originally seen Bear Island Lighthouse in 1971 and had attempted to buy or lease it to no avail. By 1989, the house had fallen into such poor condition that it took three years of renovation before Morad and Martens could move in.

Bear Island Light is best viewed by boat; click here for more information.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John G. Bowen (1839-1842, 1844-1850, 1853-1855); Solomon L. Howes (1842-1844); Levi Robinson (1850-1853); Caleb Gould (1855-1869); William Fennelly (1869-1876); Stephen Smallidge (1876-1883); Alden H. Jordan (1883-1899); Lewis F. Sawyer (1899-1909); H. G. Sawyer (c. 1916); Earle Benson (1929-1930); Elmo .J. Turner (c. 1930s), Truman Lathrop (c. 1930s), Andrew W. Kennedy (c. 1946), Carroll Alley (Coast Guard c. 1952-1955), David Sparks (Coast Guard, c. 1957-1959); Terry Stanley (Coast Guard, c. 1959), John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1960s); Clifton "Frank" Olsen Sr. (Coast Guard, Sept. 1964 - Sept. 1965); Larry Conley (Coast Guard, 1965-1968); Frederick Coyle (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); Stephen Cancellare (Coast Guard, 1976-1978); Steve Oliver (Coast Guard, c. 1980)

John G. Bowen (1839-1842, 1844-1850, 1853-1855); Solomon L. Howes (1842-1844); Levi Robinson (1850-1853); Caleb Gould (1855-1869); William Fennelly (1869-1876); Stephen Smallidge (1876-1883); Alden H. Jordan (1883-1899); Lewis F. Sawyer (1899-1909); H. G. Sawyer (c. 1916); Earle Benson (1929-1930); Elmo .J. Turner (c. 1930s), Truman Lathrop (c. 1930s), Andrew W. Kennedy (c. 1946), Carroll Alley (Coast Guard c. 1952-1955), David Sparks (Coast Guard, c. 1957-1959); Terry Stanley (Coast Guard, c. 1959), John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1960s); Clifton "Frank" Olsen Sr. (Coast Guard, Sept. 1964 - Sept. 1965); Larry Conley (Coast Guard, 1965-1968); Frederick Coyle (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); Stephen Cancellare (Coast Guard, 1976-1978); Steve Oliver (Coast Guard, c. 1980)

Defense Attorney Resources: Criminal Defense Attorney Dayton / Civil vs. Criminal Cases / Career as an Attorney