History of Mount Desert Rock Light, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Mount Desert Rock is the farthest land on which a New England coast lighthouse shows its warning 'light in the window.' ...A strange sight, indeed, in a strange place! -- rising above the waves like the last monument of some buried city of antediluvian times... A bare rock, drenched by every gale, holds the light-tower high above the waves. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Far-flung Mount Desert Rock Light is one of the most dramatically isolated of all American lighthouses. More than 20 miles from the nearest port at Mount Desert Island, the low-lying, waveswept rock is, as historian Edward Rowe Snow put it, like "part of another world." George Putnam, for many years the commissioner of the Bureau of Lighthouses, regarded Mount Desert Rock as the most exposed light station in the United States. The tiny rock is only about 17 feet above sea level at its highest point.

The French explorer Samuel de Champlain, during his visit to the area in 1604, named Mount Desert Rock and the much larger Mount Desert Island. The name is traditionally pronounced "dessert," like the last course of a meal. Congress appropriated $5,000 for a lighthouse on Mount Desert Rock on March 2, 1829, to aid mariners heading to Frenchman and Blue Hill Bays from the south. The light went into operation on August 25, 1830, with a fixed white light 44 feet above mean high water. Esais Preble was the first keeper and his son, William, was his assistant.

The French explorer Samuel de Champlain, during his visit to the area in 1604, named Mount Desert Rock and the much larger Mount Desert Island. The name is traditionally pronounced "dessert," like the last course of a meal. Congress appropriated $5,000 for a lighthouse on Mount Desert Rock on March 2, 1829, to aid mariners heading to Frenchman and Blue Hill Bays from the south. The light went into operation on August 25, 1830, with a fixed white light 44 feet above mean high water. Esais Preble was the first keeper and his son, William, was his assistant.

The first lighthouse took the form of a short wooden tower at one end of a stone keeper's dwelling, with a system of ten lamps fueled by whale oil. The structure weathered many storms before being replaced for $15,000 by a new 58-foot granite tower in 1847.

The new tower was designed by the noted architect Alexander Parris, and the contractor who built it was Joseph W. Coburn of Boston. In 1858, a new lantern was installed along with a third-order Fresnel lens exhibiting a fixed white light. A rotating fourth-order lens replaced the third-order Fresnel lens in 1898, and the characteristic was changed from fixed to a white light flashing every 15 seconds.

A second dwelling, a one-and-one-half-story wood-frame house, was added to the station in 1876. The old stone dwelling was replaced by a wood-frame double dwelling in 1893, providing accommodations for two keepers and their families. Several new outbuildings were added around the same time, and 250 feet of planked walkways were added between the buildings.

A second dwelling, a one-and-one-half-story wood-frame house, was added to the station in 1876. The old stone dwelling was replaced by a wood-frame double dwelling in 1893, providing accommodations for two keepers and their families. Several new outbuildings were added around the same time, and 250 feet of planked walkways were added between the buildings.

In 1853, Albert Wood, captain of the steamer Admiral, made a case for a fog bell at Mount Desert Rock. "If a bell were ringing in thick weather," he wrote, "instead of trying to avoid the rock, navigators would calculate to go within hearing distance, get a new course, and proceed up the bay with much more safety."

From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

Other local mariners agreed, and an open-frame bell tower, with a 1500-pound fog bell operated by a striking mechanism, was installed in 1856.

In 1889, the Lighthouse Board made a case for a powerful fog whistle. Congress soon appropriated $4500 and the new signal was installed.

A December 1878 newspaper reported on a particularly bad storm at Mount Desert Rock:

Last Tuesday night there swept along the coast of Maine... one of the severest gales that has been experienced in this latitude for years. On the shores of Mount Desert and the other islands around the mouth of the Penobscot and on the main land it was very severe, and out on Mount Desert Rock it must have been terribly wild...

In 1889, the Lighthouse Board made a case for a powerful fog whistle. Congress soon appropriated $4500 and the new signal was installed.

A December 1878 newspaper reported on a particularly bad storm at Mount Desert Rock:

Last Tuesday night there swept along the coast of Maine... one of the severest gales that has been experienced in this latitude for years. On the shores of Mount Desert and the other islands around the mouth of the Penobscot and on the main land it was very severe, and out on Mount Desert Rock it must have been terribly wild...

On Wednesday evening, the night after the storm, no light was seen in the direction of the rock. Grave fears were entertained that the lighthouse had been washed away, and that the keeper and his family had perished. Thursday and Friday nights passed, and the long-looked-for light was still missing. Then the belief became general that disaster must have befallen the light-house, and it was generally supposed that the house and its inmates had sunk beneath the waves. Owing to the roughness of the sea, there could be no communication with the rock.

From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

That Saturday night a light was finally seen and it was learned that the keeper and his family had somehow weathered the storm.

In Lighthouses of New England, Edward Rowe Snow told the story of an unusual wreck in the vicinity of Mount Desert Rock in the 1880s. The schooner Helen and Mary, carrying granite from Halifax, sank in a storm near the island. The captain's wife, who was also the sister of the first mate, was on board with her baby girl. When the vessel sank the first mate was able to survive by clinging to some wreckage.

As he drifted the mate saw a package floating by. He snatched it from the water and found that it was his sister's baby girl wrapped in oilskin. Air trapped inside the wrapping had kept the baby afloat. The mate held the child close to him through the night and the next day the pair was picked up by the crew of the lighthouse tender Iris.

In Lighthouses of New England, Edward Rowe Snow told the story of an unusual wreck in the vicinity of Mount Desert Rock in the 1880s. The schooner Helen and Mary, carrying granite from Halifax, sank in a storm near the island. The captain's wife, who was also the sister of the first mate, was on board with her baby girl. When the vessel sank the first mate was able to survive by clinging to some wreckage.

As he drifted the mate saw a package floating by. He snatched it from the water and found that it was his sister's baby girl wrapped in oilskin. Air trapped inside the wrapping had kept the baby afloat. The mate held the child close to him through the night and the next day the pair was picked up by the crew of the lighthouse tender Iris.

In the 1880s there were three keepers living at Mount Desert Rock with their families. A teacher from Southwest Harbor visited in the summer to teach the children.

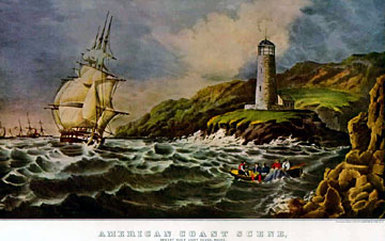

Currier & Ives print of Mount Desert Rock

In December 1902, the New York tugboat Astral, with a barge in tow, ran aground at Mount Desert Rock in a gale with 18 men aboard. The situation looked hopeless, but with the arrival of low tide Keeper Fred Robbins and an assistant (Charles H. Newman or William H. C. Dodge) managed to get close enough to the vessel to get a line aboard. All the men except one who had already frozen to death were pulled to safety. The keeper's wife prepared steaming coffee for the survivors, and salve applied to the men's freezing limbs enabled them to recover fully.

The crew of the Astral remained at Mount Desert Rock until the storm subsided six days later. Meanwhile, the barge that was being towed by the tug drifted all the way to Rockland with several men safely aboard.

The crew of the Astral remained at Mount Desert Rock until the storm subsided six days later. Meanwhile, the barge that was being towed by the tug drifted all the way to Rockland with several men safely aboard.

Despite its isolation, Mount Desert Rock was for many years a family station. It became a tradition each spring for the families to bring soil to the island for a garden, and local fishermen made contributions of earth from the mainland. By the summer a beautiful flower garden would be in bloom.

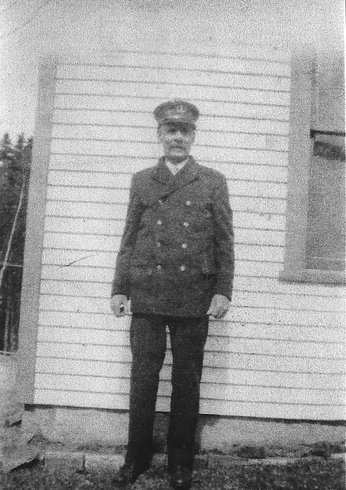

Keeper Vinal Beal. Courtesy of the Smith family.

With luck the flowers would remain until fall, but the first gales of winter would sweep the rock clean of the last bit of dirt. One woman who grew up on Mount Desert Rock told Mary Ellen Chase, author of The Story of Lighthouses:

The people who sailed past called it God's Rock Garden, but it was really mine. I never gave Him my garden, but I've thanked Him all my life for Mount Desert Rock.

Vinal O. Beal was one of the keepers at the station between 1909 and 1931. His daughter Robena described the unusual way her parents had of making sure she and her siblings were safe when playing outside. A line was attached to Robena's waist, with the other end looped around a clothesline that extended from the house to a derrick. This way the children could not be washed away.

In a paper she wrote in high school, Robena wrote about a storm on the Rock:

Once during a bad storm the sea made up so rough that the waves came up around one of the hen houses that stood along side of the tower and washed it about twenty feet and landed it upon the platform in front of the tower with the hens in it. The tide was ebbing so there was not another sea that came within reach of it.

During storms like these the water washes upon the piazza and the spray comes against the windows and the keepers have to watch their chance to run to the tower to light the light and attend to the fog signal. After one of those storms I have seen it to be at least six weeks before the mail boat could make a landing with the mail and provisions.

The people who sailed past called it God's Rock Garden, but it was really mine. I never gave Him my garden, but I've thanked Him all my life for Mount Desert Rock.

Vinal O. Beal was one of the keepers at the station between 1909 and 1931. His daughter Robena described the unusual way her parents had of making sure she and her siblings were safe when playing outside. A line was attached to Robena's waist, with the other end looped around a clothesline that extended from the house to a derrick. This way the children could not be washed away.

In a paper she wrote in high school, Robena wrote about a storm on the Rock:

Once during a bad storm the sea made up so rough that the waves came up around one of the hen houses that stood along side of the tower and washed it about twenty feet and landed it upon the platform in front of the tower with the hens in it. The tide was ebbing so there was not another sea that came within reach of it.

During storms like these the water washes upon the piazza and the spray comes against the windows and the keepers have to watch their chance to run to the tower to light the light and attend to the fog signal. After one of those storms I have seen it to be at least six weeks before the mail boat could make a landing with the mail and provisions.

Henry C. Ray, an assistant keeper, died in May 1920 when a boat overturned at the landing slip. Another assistant, Maurice Beal, survived the incident. Ray was 43 years old and left a wife and son.

Keeper George York (Courtesy of College of the Atlantic)..

Arthur E. Ginn was one of the keepers for a few years around 1920. Ginn lived at the station with his wife, Inez, and their three daughters. During this time, a teacher came to the station for 10 days each month.

One day, while Ginn was away getting supplies, a thick fog rolled in. According to family tradition, Ginn's daughters and the children of the other keepers sounded a fog signal (probably a backup bell) for hours so that Ginn would find his way back. He got back safely with the aid of his compass.

George York was keeper from 1928 to 1936. His son Wilbur was only two years old when they moved into the station. He later remembered some details of life there -- helping his father polish brass and lugging coal for the stove, and the excitement of monthly runs for supplies, like 50-pound sacks of flour and 25-pound tubs of peanut butter.

Once, after a storm, the supply boat couldn't get in and the York family nearly starved, living on biscuits and molasses. Wilbur's stepmother ran out of lard for biscuits the day before the supplies finally arrived.

In 1931-32, a navigational radio beacon was installed at Mount Desert Rock, and generators brought electricity to the light and keeper's house.

One day, while Ginn was away getting supplies, a thick fog rolled in. According to family tradition, Ginn's daughters and the children of the other keepers sounded a fog signal (probably a backup bell) for hours so that Ginn would find his way back. He got back safely with the aid of his compass.

George York was keeper from 1928 to 1936. His son Wilbur was only two years old when they moved into the station. He later remembered some details of life there -- helping his father polish brass and lugging coal for the stove, and the excitement of monthly runs for supplies, like 50-pound sacks of flour and 25-pound tubs of peanut butter.

Once, after a storm, the supply boat couldn't get in and the York family nearly starved, living on biscuits and molasses. Wilbur's stepmother ran out of lard for biscuits the day before the supplies finally arrived.

In 1931-32, a navigational radio beacon was installed at Mount Desert Rock, and generators brought electricity to the light and keeper's house.

Eighteen-year-old Peter A. Valov, a native of Los Angeles, came to Mount Desert Rock as one of the Coast Guard keepers in February 1947, after boot camp training in Florida and a period as a crewman on a ship that passed through the Panama Canal. The young Valov spent two winters on the Rock. By staying for extended periods, he saved us his leave time so he could get an occasional 30-day shore leave.

On October 6, 1962, Hurricane Daisy struck the Rock, destroying the walkway between the house and tower, as well as sweeping away fuel tanks and other structures. The three Coast Guardsmen there at the time spent the night near the top of the lighthouse tower. One of the men, John Baxter, said later:

The bad thing was that when we went in the tower you could feel the tower sway, like someone was shaking it. It was scary! The next morning, when things calmed down, we went outside the tower. We had an engine room, probably 90 feet by 90 feet. And it was gone. Crushed. A boulder had rolled up onto the bank and just crushed it. That was really scary then, because we got thinking. What if that boulder had hit that tower? It would've knocked that over, or done a good job on it. There's no way we would've survived it.

In spite of the arrival of modern conveniences like television, life for Coast Guard keepers at Mount Desert Rock wasn't much easier than it had been for Lighthouse Service keepers. 20-year-old Douglas Nute, a native of St. Louis, told author Bill Caldwell that he was "ready to scream" after a week at the station. Nute had previously been stationed on Great Duck Island; there, at least, were trees and grass and some space to walk around.

In the mid-1970s the Coast Guard removed the lantern of Mount Desert Rock Light to make room for rotating aerobeacons. A combination of public complaints and storm damage to the aerobeacons convinced the Coast Guard to install a new lantern in 1985.

Glenn Gearheart, a Coast Guard keeper in 1974-75, later described the boat access on the Rock: "We would row in supplies from a 44-foot motor lifeboat. The weather had to be perfect."

The bad thing was that when we went in the tower you could feel the tower sway, like someone was shaking it. It was scary! The next morning, when things calmed down, we went outside the tower. We had an engine room, probably 90 feet by 90 feet. And it was gone. Crushed. A boulder had rolled up onto the bank and just crushed it. That was really scary then, because we got thinking. What if that boulder had hit that tower? It would've knocked that over, or done a good job on it. There's no way we would've survived it.

In spite of the arrival of modern conveniences like television, life for Coast Guard keepers at Mount Desert Rock wasn't much easier than it had been for Lighthouse Service keepers. 20-year-old Douglas Nute, a native of St. Louis, told author Bill Caldwell that he was "ready to scream" after a week at the station. Nute had previously been stationed on Great Duck Island; there, at least, were trees and grass and some space to walk around.

In the mid-1970s the Coast Guard removed the lantern of Mount Desert Rock Light to make room for rotating aerobeacons. A combination of public complaints and storm damage to the aerobeacons convinced the Coast Guard to install a new lantern in 1985.

Glenn Gearheart, a Coast Guard keeper in 1974-75, later described the boat access on the Rock: "We would row in supplies from a 44-foot motor lifeboat. The weather had to be perfect."

The Coast Guard crew constructed a helicopter pad in the mid-1970s. "It took one good storm to wipe it out," said Glenn Gearheart. "There was nothing like watching waves washing over the whole island. We were in the lighthouse. The whole island was vibrating."

U.S. Coast Guard

One of the last Coast Guard keepers, Roger Moore, later recalled that the periods of duty on MDR could seem long. "If you didn't like the guy you were out there with, too bad," he said. He also recalled that local lobstermen would come close to the island and would toss lobsters onto the rocks for the Coast Guard keepers.

Rob Runnels, the last officer in charge, later wrote:

I was privileged with the opportunity as such and was a big part of my life then and now still after all these years!! It was a fine tradition and the light I shall always remember as a fantastic experience and great responsibility. I worked in conjunction with a civilian work crew in the automation of the light, and enjoyed spending time with the Atlantic Whale Watch.

The last Coast Guard keepers were removed by helicopter when the station was automated in late 1977. The light station was then leased to Bar Harbor's College of the Atlantic for use as a whale watching station. The college's Allied Whale program compiles and maintains catalogs for the North Atlantic populations of finback and humpback whales.

Rob Runnels, the last officer in charge, later wrote:

I was privileged with the opportunity as such and was a big part of my life then and now still after all these years!! It was a fine tradition and the light I shall always remember as a fantastic experience and great responsibility. I worked in conjunction with a civilian work crew in the automation of the light, and enjoyed spending time with the Atlantic Whale Watch.

The last Coast Guard keepers were removed by helicopter when the station was automated in late 1977. The light station was then leased to Bar Harbor's College of the Atlantic for use as a whale watching station. The college's Allied Whale program compiles and maintains catalogs for the North Atlantic populations of finback and humpback whales.

Researcher Tim Cole told the Christian Science Monitor in 1988: I like to get up into the tower maybe a half-hour before sunrise. As the sky lightens, things gradually start to happen -- more birds fly by, or a few whales become visible. You can sit and watch as the world starts to move.

Inside the base of the tower

Under the Maine Lights Program coordinated by the Island Institute of Rockland, Mount Desert Rock Light, along with Great Duck Island Light, became the property of the College of the Atlantic in 1998.

The property has taken a beating in some recent storms, particularly Hurricane Bill in 2009. If you would like to find out more about how you can help the marine mammal research effort at Mount Desert Rock, please call Allied Whale at 207-288-5644.

Use the player below to hear an interview with Sean Todd, director of Allied Whale for College of the Atlantic, on "Light Hearted," the podcast of the U.S. Lighthouse Society (July 2020).

The property has taken a beating in some recent storms, particularly Hurricane Bill in 2009. If you would like to find out more about how you can help the marine mammal research effort at Mount Desert Rock, please call Allied Whale at 207-288-5644.

Use the player below to hear an interview with Sean Todd, director of Allied Whale for College of the Atlantic, on "Light Hearted," the podcast of the U.S. Lighthouse Society (July 2020).

The lighthouse is best seen by private boat or from the air, although whale watches from Bar Harbor occasionally pass near Mount Desert Rock.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Esais Preble (1833-1835); Benjamin Ward Jr. (1841-?); Jacob L. Richardson (1848-1850); David King (1850-1853); Rufus King (1853-1859); George Booth (1859-1860); Joseph Hopkins (1860-1861); William E. Holden (1861-1864); Seth H. Higgins (assistant 1864-1865, principal keeper 1865-1867); J. A. Williken (1867-1868); Otis W. Kent (1868-1872); Amos B. Newman (1872-1881); James A. Morris (1881-1882); Thomas R. Milan (1882-1902); Fred M. Robbins, second assistant (1898-1899), then first assistant (1899-1902) then principal keeper (1902-1911); Vinal O. Beal, second assistant (1909-1910), first assistant (1910-1911), then principal keeper (1911-c. 1919 and 1924-1931); Arthur Edward Ginn (c. 1918-early 1920s); R. W. Powers (c. 1928); George York (1928-1936); Robert G. Wass (c. 1930s); Jarvis Barnett (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1946-1948); Ralph Demons (or Demmons) (c. 1948-?); Ray W. Van Nostrand (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. late 1960s, early 1970s); Robin Runnels (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1970s), Melvin Davis, Jr. (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1977)

Assistant keepers: William Preble (1833-1835); William H. Ward (1855-1858); John Dolliver Jr. (1858-1859); B. Thurber (1859-1864); David Rollins (1865-1867); Dan Ladd (1865); William Gilley (1867); Dan B. Eaton (1867-1871); Perry W. Richardson (1868-1870 and 1871-1872); Amos B. Newman (1870-1872); Mark W. Hodgson, (1872-1882); William P. Sawyer, second assistant (1872-1878); James A. Morris (1874-1876); Frank Collins (1876-1877); Howard P. Robbins, second assistant (1878-1882); William Stanley, assistant (1882-1883); Benjamin Maddox (1883-1888); Howard M. Gilley, second assistant (1883-1887); Lewis F. Sawyer, second assistant (1887-1888), then first assistant (1888-1889); Willis Dolliver, second assistant (1887-1890), then first assistant (1890-1891); William J, Newman, second assistant (1890), then first assistant (1890); Thomas R. Savage, second assistant (1891-1892); Orrin L. Milan, second assistant (1892-1895), then first assistant (1895-1897); Charles Thurston, second assistant (1895-1897), then first assistant (1897-1899); Joseph M. Gray (1900-1901); Bert Richard (c. 1901); Herbert P. Richardson, second assistant (c. 1902); Charles H. Newman (c. 1902-1908); William H. C. Dodge, second assistant (c. 1902-1908); W. P. Kent (1909-1910); Wilbert F. Lurney (or Lurvey?) second assistant (1910), then first assistant (1911-?); Charles A. Radley, second assistant (1911-?); Albert Staples (c. 1920); Henry C. Ray, assistant (c. 1920); Maurice R. Beal (assistant, c. 1920); Joseph Muise (c. 1920s); Edward Elliot (c. 1923-1930); A. H. Kennedy (c. 1932); Everett Quinn, assistant (c. 1935); Peter A. Valov (Coast Guard, Feb. 4, 1947 - April 8, 1948); M. J. Hergatt (Coast Guard, c. 1948); H. B. Clement (Coast Guard, c. 1948); Roy Ivan Smith (Coast Guard, c. mid to late 1950s); John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1962); Paul Francis Kent (Coast Guard, c. late 1960s); James White (Coast Guard, 1969-1971); Russ Allyson (Coast Guard, 1971-1972); Gary L. Crossman (Coast Guard, 1973-1974); Glenn Gearhart (Coast Guard, 1974-1975); Roger Moore (Coast Guard, 1976-1977); Robin Runnels (Coast Guard, c. 1977); Douglas Nute (Coast Guard, ?-1977); Richard "Rick" Fox (Coast Guard, c. 1970s)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Esais Preble (1833-1835); Benjamin Ward Jr. (1841-?); Jacob L. Richardson (1848-1850); David King (1850-1853); Rufus King (1853-1859); George Booth (1859-1860); Joseph Hopkins (1860-1861); William E. Holden (1861-1864); Seth H. Higgins (assistant 1864-1865, principal keeper 1865-1867); J. A. Williken (1867-1868); Otis W. Kent (1868-1872); Amos B. Newman (1872-1881); James A. Morris (1881-1882); Thomas R. Milan (1882-1902); Fred M. Robbins, second assistant (1898-1899), then first assistant (1899-1902) then principal keeper (1902-1911); Vinal O. Beal, second assistant (1909-1910), first assistant (1910-1911), then principal keeper (1911-c. 1919 and 1924-1931); Arthur Edward Ginn (c. 1918-early 1920s); R. W. Powers (c. 1928); George York (1928-1936); Robert G. Wass (c. 1930s); Jarvis Barnett (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1946-1948); Ralph Demons (or Demmons) (c. 1948-?); Ray W. Van Nostrand (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. late 1960s, early 1970s); Robin Runnels (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1970s), Melvin Davis, Jr. (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. 1977)

Assistant keepers: William Preble (1833-1835); William H. Ward (1855-1858); John Dolliver Jr. (1858-1859); B. Thurber (1859-1864); David Rollins (1865-1867); Dan Ladd (1865); William Gilley (1867); Dan B. Eaton (1867-1871); Perry W. Richardson (1868-1870 and 1871-1872); Amos B. Newman (1870-1872); Mark W. Hodgson, (1872-1882); William P. Sawyer, second assistant (1872-1878); James A. Morris (1874-1876); Frank Collins (1876-1877); Howard P. Robbins, second assistant (1878-1882); William Stanley, assistant (1882-1883); Benjamin Maddox (1883-1888); Howard M. Gilley, second assistant (1883-1887); Lewis F. Sawyer, second assistant (1887-1888), then first assistant (1888-1889); Willis Dolliver, second assistant (1887-1890), then first assistant (1890-1891); William J, Newman, second assistant (1890), then first assistant (1890); Thomas R. Savage, second assistant (1891-1892); Orrin L. Milan, second assistant (1892-1895), then first assistant (1895-1897); Charles Thurston, second assistant (1895-1897), then first assistant (1897-1899); Joseph M. Gray (1900-1901); Bert Richard (c. 1901); Herbert P. Richardson, second assistant (c. 1902); Charles H. Newman (c. 1902-1908); William H. C. Dodge, second assistant (c. 1902-1908); W. P. Kent (1909-1910); Wilbert F. Lurney (or Lurvey?) second assistant (1910), then first assistant (1911-?); Charles A. Radley, second assistant (1911-?); Albert Staples (c. 1920); Henry C. Ray, assistant (c. 1920); Maurice R. Beal (assistant, c. 1920); Joseph Muise (c. 1920s); Edward Elliot (c. 1923-1930); A. H. Kennedy (c. 1932); Everett Quinn, assistant (c. 1935); Peter A. Valov (Coast Guard, Feb. 4, 1947 - April 8, 1948); M. J. Hergatt (Coast Guard, c. 1948); H. B. Clement (Coast Guard, c. 1948); Roy Ivan Smith (Coast Guard, c. mid to late 1950s); John Baxter (Coast Guard, c. 1962); Paul Francis Kent (Coast Guard, c. late 1960s); James White (Coast Guard, 1969-1971); Russ Allyson (Coast Guard, 1971-1972); Gary L. Crossman (Coast Guard, 1973-1974); Glenn Gearhart (Coast Guard, 1974-1975); Roger Moore (Coast Guard, 1976-1977); Robin Runnels (Coast Guard, c. 1977); Douglas Nute (Coast Guard, ?-1977); Richard "Rick" Fox (Coast Guard, c. 1970s)