History of Faulkner's Island Light, Guilford, Connecticut

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More Information: Front Page / Photos / Bibliography / Postcards

Click here for a Smugmug gallery of Faulkner's Island Light photos (prints and gift items available)

Faulkner's Island Light is Connecticut's second oldest lighthouse and also the only active light station on an island in the state.

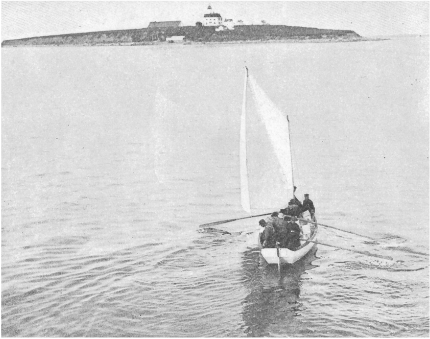

Late 1800s photo of a supply boat headed for Faulkner's Island

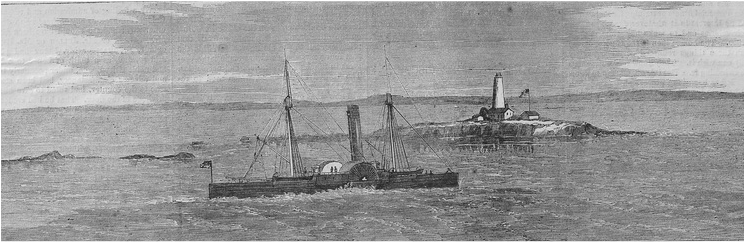

Faulkner's Island is about three and one half miles offshore from the town of Guilford. Many vessels negotiating Long Island Sound were wrecked on the rocks around the three-acre island, prompting the Lighthouse Establishment to erect a 40-foot stone lighthouse in 1802.

The beacon was commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, and the island was purchased from Medad Stone for $325. Like Connecticut's oldest lighthouse tower, New London Harbor Light, Faulkner's Island Light was built by stonemason Abisha Woodward.

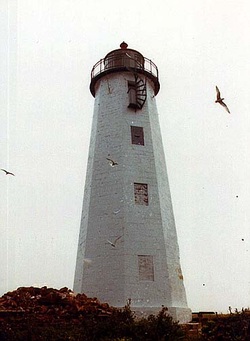

The lighthouse is notable for the unusual outside staircase on its upper section, leading to the gallery deck.

Shipping accidents continued in the vicinity after the establishment of the lighthouse. On one occasion the first keeper, Joseph Griffing, found the bodies of seven sailors whose vessel was wrecked nearby. Griffing buried the men on neighboring Goose Island.

The beacon was commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, and the island was purchased from Medad Stone for $325. Like Connecticut's oldest lighthouse tower, New London Harbor Light, Faulkner's Island Light was built by stonemason Abisha Woodward.

The lighthouse is notable for the unusual outside staircase on its upper section, leading to the gallery deck.

Shipping accidents continued in the vicinity after the establishment of the lighthouse. On one occasion the first keeper, Joseph Griffing, found the bodies of seven sailors whose vessel was wrecked nearby. Griffing buried the men on neighboring Goose Island.

During the War of 1812, British troops stopped at Faulkner's. They did no harm to the tower or Keeper Solomon Stone and his family, realizing the importance of the lighthouse to their own safety.

President James Monroe appointed Guilford native Eli Kimberly keeper in 1818 at a salary of $350 per year. Kimberly moved to the island with his pregnant wife Polly and their two children.

The family remained on Faulkner's Island for 33 years, raising 12 children. The Kimberlys kept livestock and raised vegetables on the island, and the children were taught by a tutor who boarded with the family.

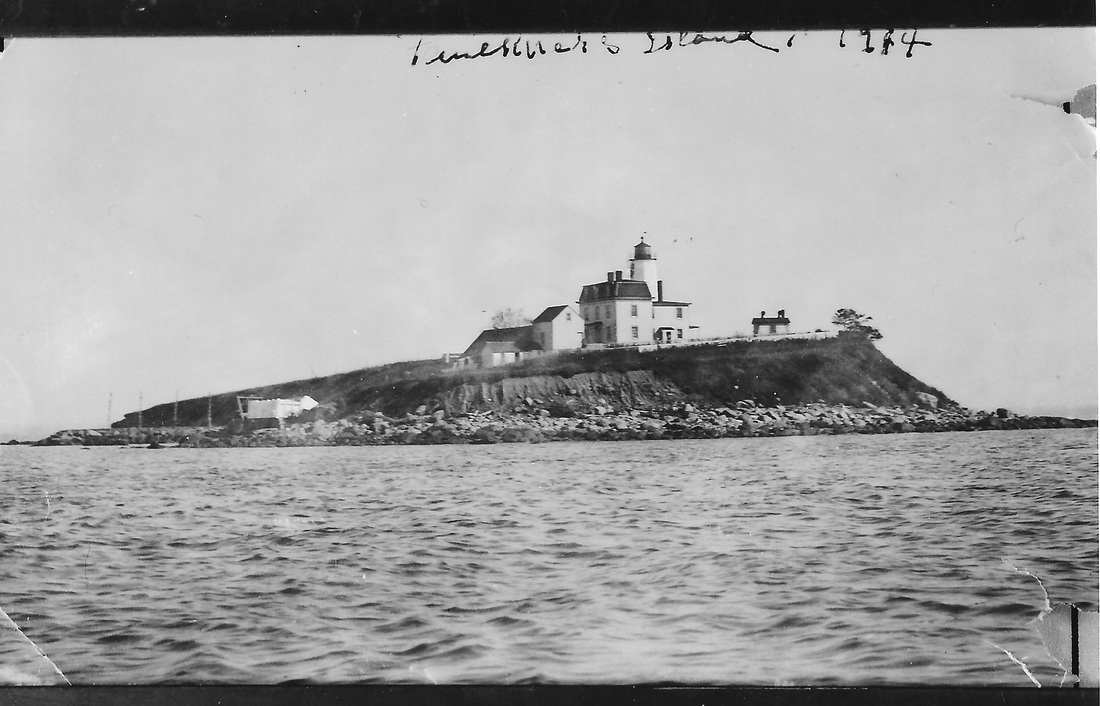

Right: Faulkner's Island Light Station in the late 19th century. Robert Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, Photography Collection, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints & Photographs, the New York Public Library.

The family remained on Faulkner's Island for 33 years, raising 12 children. The Kimberlys kept livestock and raised vegetables on the island, and the children were taught by a tutor who boarded with the family.

Right: Faulkner's Island Light Station in the late 19th century. Robert Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, Photography Collection, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints & Photographs, the New York Public Library.

Visitors were common during the Kimberlys' years on the island, often as many as 100 people on a summer day.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

_Faulkner Island Light's original lantern was replaced in 1840. The old lighting system, consisting of twelve whale-oil lamps with parabolic reflectors, was replaced by a a system of nine lamps and reflectors. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed in 1856. It's believed that the present lantern was installed about 1870. The original keeper's house had fallen into disrepair and was rebuilt in 1858.

Oliver N. Brooks served as keeper from 1851 to 1882. Over one hundred vessels were wrecked in the vicinity during his tenure, through no fault of the light or its keeper.

In November 1858, Brooks rescued five people from the grounded schoonerMoses F. Webb. He received a gold medal from the New York Life Saving Society for his heroism, and his salary was soon raised to $500 per year.

Keeper Brooks was known as a man of many interests. He played the violin, studied ornithology and taxidermy, and conducted experiments with sound and light. He often practiced his taxidermy skills on unfortunate birds that had collided with the lighthouse lantern and died, and the keeper's house became kind of a natural history museum.One of the keeper's daughters reportedly also shot a number of birds to add to the collection. Another daughter studied marine botany and painted watercolors.

The entire Brooks family played musical instruments, and visitors were sometimes treated to impromptu concerts. According to an 1888 newspaper article, the Brooks family "made a paradise out of that little island."

Frank Ward Parmele, a Guilford native, was an assistant keeper 1884-90. A descendant of Parmele wrote the following in August 2009: "On February 14, 1888, during a snowstorm, his wife, Lillian Norton Parmele, went into labor and was carried by rowboat from Faulkner's Island to the mainland where she was transported by oxcart to 6 State Street in Guilford where my grandfather, David V. Parmelee was born."

Parmele went on to serve more than 20 years as keeper of Castle Hill Light in Newport, Rhode Island.George Zuius was the last keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Service, leaving Faulkner's Island in 1941 when the Coast Guard took over. Keeper Zuius was on Faulkner's Island when the Hurricane of 1938 hit. He managed to keep the light going throughout the storm, but the boathouse was destroyed. Zuius' daughter, Barbara, still remembers playing on the island with a pet chicken and her dog Rexie.

Oliver N. Brooks served as keeper from 1851 to 1882. Over one hundred vessels were wrecked in the vicinity during his tenure, through no fault of the light or its keeper.

In November 1858, Brooks rescued five people from the grounded schoonerMoses F. Webb. He received a gold medal from the New York Life Saving Society for his heroism, and his salary was soon raised to $500 per year.

Keeper Brooks was known as a man of many interests. He played the violin, studied ornithology and taxidermy, and conducted experiments with sound and light. He often practiced his taxidermy skills on unfortunate birds that had collided with the lighthouse lantern and died, and the keeper's house became kind of a natural history museum.One of the keeper's daughters reportedly also shot a number of birds to add to the collection. Another daughter studied marine botany and painted watercolors.

The entire Brooks family played musical instruments, and visitors were sometimes treated to impromptu concerts. According to an 1888 newspaper article, the Brooks family "made a paradise out of that little island."

Frank Ward Parmele, a Guilford native, was an assistant keeper 1884-90. A descendant of Parmele wrote the following in August 2009: "On February 14, 1888, during a snowstorm, his wife, Lillian Norton Parmele, went into labor and was carried by rowboat from Faulkner's Island to the mainland where she was transported by oxcart to 6 State Street in Guilford where my grandfather, David V. Parmelee was born."

Parmele went on to serve more than 20 years as keeper of Castle Hill Light in Newport, Rhode Island.George Zuius was the last keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Service, leaving Faulkner's Island in 1941 when the Coast Guard took over. Keeper Zuius was on Faulkner's Island when the Hurricane of 1938 hit. He managed to keep the light going throughout the storm, but the boathouse was destroyed. Zuius' daughter, Barbara, still remembers playing on the island with a pet chicken and her dog Rexie.

In March 1976 a fire broke out in the keeper's quarters while two Coast Guardsmen were on duty.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

Fire fighters couldn't arrive in time, and when the smoke cleared the 1871 keeper's house was gone and the tower was scorched. "By the time we got there the island was an inferno," said one firefighter. "We didn't stand a chance, but we did what we could."

Two years later the light was repaired and automated, with the fourth order lens being replaced by a modern optic. Vandals did further damage after the fire, so the windows were bricked up and a new steel door installed. In 1988 the light was converted to solar power.

Like many New England lighthouses, Faulkner's Island Light has been waging a war with nature. Erosion ate away at the bluff on which the lighthouse stands at a rate of at least six inches per year, until the tower stood about 35 feet from the brink.

In 1991, local resident and historian Joel Helander founded the nonprofit Faulkner's Light Brigade, a commission of the Guilford Preservation Alliance, to try to save the venerable structure. Helander said, "The lighthouse has been the salvation of so many mariners. Now it's our turn to return the favor by saving it."

The Faulkner's Light Brigade now has over 1,000 members.A restoration costing over $200,000 was completed in late 1999. Most of the funding came from the Federal Government through the Intermodal Surface Transportation Enhancement Act (ISTEA). Walter Sedovic Architects of Irvington, New York, were chosen to oversee the restoration project. Sedovic has said, "Historic buildings have a layering of time and events that's irreplaceable... I think it's remarkable to be working on a lighthouse that Jefferson commissioned and represents that period so well." Sedovic chose to restore the tower to the 1871 period.

International Chimney Corporation of Buffalo, New York -- the same company that moved two Cape Cod lighthouses, among others -- was chosen to implement the restoration of the lighthouse. The restoration includes a new ventilation system, the application of an all-white breathable coating to make the tower weathertight, painting of the lantern gallery inside and out, a new lightning protection system, installation of a stainless steel door, new 12-pane casement windows in the face of the west wall, restoration of the original weathervane and the scraping and painting of the interior handrail. Another major addition is a 75-square foot entry deck.

Two years later the light was repaired and automated, with the fourth order lens being replaced by a modern optic. Vandals did further damage after the fire, so the windows were bricked up and a new steel door installed. In 1988 the light was converted to solar power.

Like many New England lighthouses, Faulkner's Island Light has been waging a war with nature. Erosion ate away at the bluff on which the lighthouse stands at a rate of at least six inches per year, until the tower stood about 35 feet from the brink.

In 1991, local resident and historian Joel Helander founded the nonprofit Faulkner's Light Brigade, a commission of the Guilford Preservation Alliance, to try to save the venerable structure. Helander said, "The lighthouse has been the salvation of so many mariners. Now it's our turn to return the favor by saving it."

The Faulkner's Light Brigade now has over 1,000 members.A restoration costing over $200,000 was completed in late 1999. Most of the funding came from the Federal Government through the Intermodal Surface Transportation Enhancement Act (ISTEA). Walter Sedovic Architects of Irvington, New York, were chosen to oversee the restoration project. Sedovic has said, "Historic buildings have a layering of time and events that's irreplaceable... I think it's remarkable to be working on a lighthouse that Jefferson commissioned and represents that period so well." Sedovic chose to restore the tower to the 1871 period.

International Chimney Corporation of Buffalo, New York -- the same company that moved two Cape Cod lighthouses, among others -- was chosen to implement the restoration of the lighthouse. The restoration includes a new ventilation system, the application of an all-white breathable coating to make the tower weathertight, painting of the lantern gallery inside and out, a new lightning protection system, installation of a stainless steel door, new 12-pane casement windows in the face of the west wall, restoration of the original weathervane and the scraping and painting of the interior handrail. Another major addition is a 75-square foot entry deck.

With help from the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Congress in September 1996 appropriated part of the erosion control funds.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

The balance of the $4.5 million was appropriated in 1998. The U.S. Army Corps plan for preservation is designed to withstand a 50-year storm.

In September 2000 an armada of heavy construction equipment arrived on the island under the direction of Zenone, Inc., of Franklin, Massachusetts. A massive stone wall nearly 20 feet high and 50 feet wide was installed along the east embankment, with an outer layer consisting of stones weighing as much as three tons each.

The upper face of the embankment was cut back to a slope of about 30-40 degrees, and hardy vegetation was planted to help buffer wind and rain. Next to the lighthouse for 300 feet, additional stability was created by the placement of six-inch high "geo cells," a system of plastic fabric with holes, covered with earth and planted with vegetation. In all, 600 linear feet of the east embankment were stabilized under Phase 1 of the erosion control project.

More restoration of the lighthouse took place in 2010. View the videos below for more information.

In September 2000 an armada of heavy construction equipment arrived on the island under the direction of Zenone, Inc., of Franklin, Massachusetts. A massive stone wall nearly 20 feet high and 50 feet wide was installed along the east embankment, with an outer layer consisting of stones weighing as much as three tons each.

The upper face of the embankment was cut back to a slope of about 30-40 degrees, and hardy vegetation was planted to help buffer wind and rain. Next to the lighthouse for 300 feet, additional stability was created by the placement of six-inch high "geo cells," a system of plastic fabric with holes, covered with earth and planted with vegetation. In all, 600 linear feet of the east embankment were stabilized under Phase 1 of the erosion control project.

More restoration of the lighthouse took place in 2010. View the videos below for more information.

|

|

|

More than 150 species of birds use Faulkner's Island, which is part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge, as a migratory rest stop.

U.S. Coast Guard photo c. 1980s

The island has one of the northeast's largest breeding colonies of roseate terns, an endangered species. Access to the island is restricted during nesting season (May to August

Faulkner's Island Light, still an active aid to navigation, can be seen distantly from shore but is best viewed by boat. There is an annual open house held each September, but visitors must provide their own boat transportation.).

The rescue of Faulkner's Island Light is well underway, but the Faulkner's Light Brigade needs all the help they can get. Says supporter and boater Ken McKenzie, "Without the lighthouse, the island would sure seem like a strange place to me." Please help by sending your donation to:

Faulkner's Light Brigade

P.O. Box 444

Guilford, Connecticut 06437

(203) 453-8400

Below are some photos taken during a visit to the island on June 22, 2005, courtesy of Sara Williams of the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge and Fred Farnsworth of Faulkner's Light Brigade.

Faulkner's Island Light, still an active aid to navigation, can be seen distantly from shore but is best viewed by boat. There is an annual open house held each September, but visitors must provide their own boat transportation.).

The rescue of Faulkner's Island Light is well underway, but the Faulkner's Light Brigade needs all the help they can get. Says supporter and boater Ken McKenzie, "Without the lighthouse, the island would sure seem like a strange place to me." Please help by sending your donation to:

Faulkner's Light Brigade

P.O. Box 444

Guilford, Connecticut 06437

(203) 453-8400

Below are some photos taken during a visit to the island on June 22, 2005, courtesy of Sara Williams of the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge and Fred Farnsworth of Faulkner's Light Brigade.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Joseph Griffing (1802-1812); Solomon Stone, Jr. (1812-1818); Eli Kimberly (1818-1851); Oliver N. Brooks (1851-1882); Mary Brooks (assistant, 1879-1882); William Jones (1882-c. 1890); Frank Parmelee (assistant, 1884-1890); Ernest Hermann (1890-1901); Howard Poe (1901-1909); James Boyce (assistant, c. 1905); William J. Hannighan (assistant, 1906); Conrad Hawk (assistant, c. 1909); Elmer Rathbun (1909-1911); Frederick R. Campbell (assistant, 1912-1913); Arthur Jensen (1911-1916); ? Gregory (assistant, ?); Edward M. Grant (assistant, 1914); Herbert L. Greenwood (assistant 1915-1916, head keeper 1916-1919); Leonard Fuller (1919-1924); William Hardwick (assistant, c. 1920); Samuel Fuller (1924-?); Fred Braffire (assistant, c. 1924)l Robert L. Howard (c. 1927-1928); Arthur J. Minzner (assistant, c. 1928); George Zuius (1935-1941); Harold Burbine (Coast Guard, c. 1940s), Stephen Talgo (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); William Parker (Coast Guard asst. 1945-1946); Robert Baranksi (Coast Guard 1957-1958); Jim Marshall (Coast Guard, 1958-1962); Marvin White (Coast Guard, 1961); James Overton (Coast Guard officer in charge c. late 1960s); Robert Ewing (Coast Guard, c. 1965); Steve Martin (Coast Guard 1966-1970); Tony Fox (Coast Guard, c. 1973); John Von Ogden (Coast Guard, 1975-1976); Mark Robinson (Coast Guard Officer in Charge 1975-1976)

Joseph Griffing (1802-1812); Solomon Stone, Jr. (1812-1818); Eli Kimberly (1818-1851); Oliver N. Brooks (1851-1882); Mary Brooks (assistant, 1879-1882); William Jones (1882-c. 1890); Frank Parmelee (assistant, 1884-1890); Ernest Hermann (1890-1901); Howard Poe (1901-1909); James Boyce (assistant, c. 1905); William J. Hannighan (assistant, 1906); Conrad Hawk (assistant, c. 1909); Elmer Rathbun (1909-1911); Frederick R. Campbell (assistant, 1912-1913); Arthur Jensen (1911-1916); ? Gregory (assistant, ?); Edward M. Grant (assistant, 1914); Herbert L. Greenwood (assistant 1915-1916, head keeper 1916-1919); Leonard Fuller (1919-1924); William Hardwick (assistant, c. 1920); Samuel Fuller (1924-?); Fred Braffire (assistant, c. 1924)l Robert L. Howard (c. 1927-1928); Arthur J. Minzner (assistant, c. 1928); George Zuius (1935-1941); Harold Burbine (Coast Guard, c. 1940s), Stephen Talgo (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); William Parker (Coast Guard asst. 1945-1946); Robert Baranksi (Coast Guard 1957-1958); Jim Marshall (Coast Guard, 1958-1962); Marvin White (Coast Guard, 1961); James Overton (Coast Guard officer in charge c. late 1960s); Robert Ewing (Coast Guard, c. 1965); Steve Martin (Coast Guard 1966-1970); Tony Fox (Coast Guard, c. 1973); John Von Ogden (Coast Guard, 1975-1976); Mark Robinson (Coast Guard Officer in Charge 1975-1976)