History of Billingsgate Lighthouse, Wellfleet, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

On the western shore of the harbor, at the entrance, lies Billingsgate Island, a low sandy islet, triangular in shape and fringed with sand hillocks from fifteen to twenty feet high. It is surrounded in every direction by dangerous shoals and flats, many of which are bare at low water, -- so that it cannot be approached except from the harbor side. On its southeastern extremity is built the light-house which is the guide to Wellfleet Harbor. -- Atlantic Local Coast Pilot, 1880

From A Trip Around Cape Cod, 1898

In 1620, the Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower made note of a 60-acre island in Cape Cod Bay, about three miles west of the mainland at what is now the town of Eastham and a short distance south of Jeremy’s Point in Wellfleet. William Bradford described the island as “a tongue of land, being flat, off from the shore, with a sandy point.” Miles Standish and a landing party spent a night on the island, huddled around a fire on the beach.

Much of the area that now constitutes the Cape Cod towns of Wellfleet and Eastham, with plentiful fish and shellfish, was dubbed Billingsgate after a famous fish market in London, England. The name was eventually used exclusively for the island. (The British name originally was “Belinsgate,” or the “Gate of Belinus,” after its founder, Belinus, king of Britain from 380 to 374 B.C.)

Wellfleet's fishing and shellfishing industries were expanding by the 1820s, and Billingsgate Island was the ideal location for a light to guide vessels into the harbor. On May 7, 1822, Congress appropriated $2,000 for the lighthouse.

The land for the light station on Billingsgate was sold by Elizah Cobb of Brewster to the federal government in 1822 for $100. Winslow Lewis swiftly built a stone keeper's dwelling, 20 by 34 feet. The building was surmounted by an octagonal light tower extending 16 feet above its roof. William S. Moore was the first keeper at $350 per year.

The tower held a system of eight lamps and reflectors that exhibited a fixed white light, visible for 12 miles. Within a dozen years, the first lighthouse was underminded by the sea as the island's contours changed. Engineer I. W. P. Lewis's inspection of 1843 notes that a second lighthouse had been completed in 1834. The new structure was a brick dwelling with a wooden tower on the roof.

Abijah Gill, who had been keeper since 1830 at $200 per year, told Lewis that the building was leaky, and that water and sand flowed through the roof in storms. Eight lamps and reflectors were sill in use, and Lewis called the lamps “very bad,” adding that the result was a “dim uncertain light in the clearest weather.” He concluded by recommending that the lighthouse be entirely rebuilt, and that it be fitted with a single lamp “of a proper form.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, Billingsgate had a community of 30 homes, a school, and a plant for rendering oil from the pilot whales (then known as blackfish) caught nearby. Pilot whales sometimes stranded themselves in the vicinity of the lighthouse.

An 1850 inspection, when Francis Krogman was keeper, reported the lighting apparatus in good order. The report sounded an ominous note: "The island is washing away very fast." A storm in the winter of 1854-55 damaged the station, and the chairman of the recently formed Lighthouse Board suggested, in 1855, that it would be more prudent to build a new lighthouse on screwpiles "than to make further attempts to secure the permanency of the present site." He asked for, and received in the following year, an appropriation of $14,000.

Much of the area that now constitutes the Cape Cod towns of Wellfleet and Eastham, with plentiful fish and shellfish, was dubbed Billingsgate after a famous fish market in London, England. The name was eventually used exclusively for the island. (The British name originally was “Belinsgate,” or the “Gate of Belinus,” after its founder, Belinus, king of Britain from 380 to 374 B.C.)

Wellfleet's fishing and shellfishing industries were expanding by the 1820s, and Billingsgate Island was the ideal location for a light to guide vessels into the harbor. On May 7, 1822, Congress appropriated $2,000 for the lighthouse.

The land for the light station on Billingsgate was sold by Elizah Cobb of Brewster to the federal government in 1822 for $100. Winslow Lewis swiftly built a stone keeper's dwelling, 20 by 34 feet. The building was surmounted by an octagonal light tower extending 16 feet above its roof. William S. Moore was the first keeper at $350 per year.

The tower held a system of eight lamps and reflectors that exhibited a fixed white light, visible for 12 miles. Within a dozen years, the first lighthouse was underminded by the sea as the island's contours changed. Engineer I. W. P. Lewis's inspection of 1843 notes that a second lighthouse had been completed in 1834. The new structure was a brick dwelling with a wooden tower on the roof.

Abijah Gill, who had been keeper since 1830 at $200 per year, told Lewis that the building was leaky, and that water and sand flowed through the roof in storms. Eight lamps and reflectors were sill in use, and Lewis called the lamps “very bad,” adding that the result was a “dim uncertain light in the clearest weather.” He concluded by recommending that the lighthouse be entirely rebuilt, and that it be fitted with a single lamp “of a proper form.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, Billingsgate had a community of 30 homes, a school, and a plant for rendering oil from the pilot whales (then known as blackfish) caught nearby. Pilot whales sometimes stranded themselves in the vicinity of the lighthouse.

An 1850 inspection, when Francis Krogman was keeper, reported the lighting apparatus in good order. The report sounded an ominous note: "The island is washing away very fast." A storm in the winter of 1854-55 damaged the station, and the chairman of the recently formed Lighthouse Board suggested, in 1855, that it would be more prudent to build a new lighthouse on screwpiles "than to make further attempts to secure the permanency of the present site." He asked for, and received in the following year, an appropriation of $14,000.

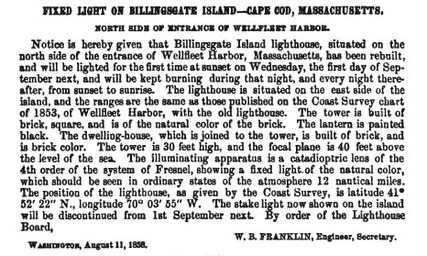

The building of the new tower and dwelling, farther to the north and on higher ground, commenced in August 1857, and the light was re-established in its new location on September 1, 1858.

Unfortunately, the new buildings -- a square lighthouse tower and attached keeper's house, both built of brick -- were not built on screwpiles, as the chairman had urged. The rapidly encroaching ocean soon threatened the new station.

Keeper Herman Dill's log entry for February 7, 1875, read:

It has been very Cold here for the last month and the most ice that i ever see in this Rigen We are almost buried up in it No salt water to be seen from the island I hav not seen a living man for over a month no prospect for the Better i do get the blues sometimes to think i can't [get] here from the main so pend up with ice that i can not move in either direction for the ice is 15 feet high in some places.

Keeper Herman Dill's log entry for February 7, 1875, read:

It has been very Cold here for the last month and the most ice that i ever see in this Rigen We are almost buried up in it No salt water to be seen from the island I hav not seen a living man for over a month no prospect for the Better i do get the blues sometimes to think i can't [get] here from the main so pend up with ice that i can not move in either direction for the ice is 15 feet high in some places.

In December 1875, the tower was flooded to a depth of three to five feet. Then, in March 1876, Keeper Dill was found dead in his boat, afloat in Cape Cod Bay the day after a brutal storm.

The third Billingsgate Lighthouse

In 1888, the Lighthouse Board tried to delay the inevitable by building 1,000 feet of jetties and bulkheads around the island.

Thomas K. Payne was keeper 1869-70 and 1876-84. On January 26, 1878, Payne wrote in the log:

[We] have had a ten days gale. West shore of island washed away very much.

In the same year, he wrote:

[We have] changed from lard oil to kerosene. I like burning kerosene very much.

Thomas K. Payne was keeper 1869-70 and 1876-84. On January 26, 1878, Payne wrote in the log:

[We] have had a ten days gale. West shore of island washed away very much.

In the same year, he wrote:

[We have] changed from lard oil to kerosene. I like burning kerosene very much.

On his last day, Payne wrote in the log:

This is our last night on the island as keeper. We are packed up and mostly moved... We have had many pleasant hours but many more very lonely ones... Remember us to friends if any. Good bye.

In a 1969 article, Earle G. Rich recalled visiting the lighthouse around 1900, when George Bailey was keeper. Bailey had a 34-foot double-ender boat, made on Cape Cod in Orleans, that he used to go to Wellfleet for supplies. The boat was equipped with a 10-horsepower gasoline engine. Rich and his brother were thrilled when the keeper invited them to accompany him on a trip to town. He always tied his boat up at a location in Wellfleet known as Puddle Dock.

In the island’s heyday, at least 35 fishermen and their families made their home on Billingsgate. There was even a schoolhouse for a while, and a restaurant and shop for summer visitors. Some of the homes on the island were floated across the bay and relocated in Eastham and Wellfleet. As the island dwindled in size, the keeper and his family were eventually the only year-round residents. The island was still frequented by plenty of visitors in summer, and was a favorite place for clambakes.

A prominent Boston surgeon named Maurice Richardson bought what was left of the island in 1897 and constructed a hunting lodge from parts of the abandoned buildings, complete with a high cupola that gave him an advantage over the waterfowl. Richardson sold the island when its area was down to five acres.

In the island’s heyday, at least 35 fishermen and their families made their home on Billingsgate. There was even a schoolhouse for a while, and a restaurant and shop for summer visitors. Some of the homes on the island were floated across the bay and relocated in Eastham and Wellfleet. As the island dwindled in size, the keeper and his family were eventually the only year-round residents. The island was still frequented by plenty of visitors in summer, and was a favorite place for clambakes.

A prominent Boston surgeon named Maurice Richardson bought what was left of the island in 1897 and constructed a hunting lodge from parts of the abandoned buildings, complete with a high cupola that gave him an advantage over the waterfowl. Richardson sold the island when its area was down to five acres.

By 1915, the foundations of the lighthouse and dwelling were undermined and the tower developed a pronounced list. The keeper was removed, the tower was secured with ropes, and a crew climbed into the lantern to remove all the lighting equipment.

The lighthouse toppled in a storm on the day after Christmas that year. For a while a light shone from the cupola of a house on the island, then a light on a skeleton tower was erected.

Billingsgate has its share of persistent legends and lore. Some blame a curse for the island’s disappearance, claiming that an innocent prisoner declared, “If I am put to death, the island will disappear,” shortly before his execution on the gallows.

There’s also the story of “Lumpkin’s Light,” a mysterious light that would appear between the island and the mainland—supposedly related to a fisherman who died mysteriously—and the “sea witch of Billingsgate,” who searched for the souls of lost sailors.

The automatic light on a steel skeleton tower at Billingsgate was discontinued in 1922, but it was re-established in 1931 at the request of local mariners. In 1933, it was replaced by a lighted bell buoy.

By 1942, the island had mostly disappeared, although a trace of it can still be spotted at low tide. Several buoys now mark Billingsgate Shoal.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William S. Moore (1822-1830), Abijah Gill (1830-1847), Elisha Cobb (1847-1849), Francis Krogman (1849-1853), Elisha Cobb (1853-?), Thomas K. Payne (1860-1869 and 1876-1884), Thomas I. Payne (1869-1870), Elisha Cobb (1870-1872), Herman Dill (1872-1876, died in service), Ira W. Ingalls (1884-1889), George W. Bailey (1900-1915)

Billingsgate has its share of persistent legends and lore. Some blame a curse for the island’s disappearance, claiming that an innocent prisoner declared, “If I am put to death, the island will disappear,” shortly before his execution on the gallows.

There’s also the story of “Lumpkin’s Light,” a mysterious light that would appear between the island and the mainland—supposedly related to a fisherman who died mysteriously—and the “sea witch of Billingsgate,” who searched for the souls of lost sailors.

The automatic light on a steel skeleton tower at Billingsgate was discontinued in 1922, but it was re-established in 1931 at the request of local mariners. In 1933, it was replaced by a lighted bell buoy.

By 1942, the island had mostly disappeared, although a trace of it can still be spotted at low tide. Several buoys now mark Billingsgate Shoal.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William S. Moore (1822-1830), Abijah Gill (1830-1847), Elisha Cobb (1847-1849), Francis Krogman (1849-1853), Elisha Cobb (1853-?), Thomas K. Payne (1860-1869 and 1876-1884), Thomas I. Payne (1869-1870), Elisha Cobb (1870-1872), Herman Dill (1872-1876, died in service), Ira W. Ingalls (1884-1889), George W. Bailey (1900-1915)