Wickford Harbor Light, North Kingstown, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Bibliography / Postcards

With increasing ferry traffic between Wickford and Newport, the Lighthouse Board's annual reports in 1878 and 1879 recommended: "Additional aids to navigation to mark the entrance to Wickford Harbor are required. A granite pier surmounted by a small light should be established on Old Gay Rock. . . . The light at Poplar Point could be discontinued if one on Old Gay is established."

On June 15, 1880, Congress appropriated $45,000 for a lighthouse on Old Gay Rock, about 200 yards offshore from the 1831 lighthouse at Poplar Point.

Right: Poplar Point Light and Wickford Harbor Light From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The lighthouse superstructure was an eight-room wood-frame Gothic Revival house much like the one constructed a few years later at the northern tip of Conanicut Island. A square lighthouse tower was attached to a corner of the dwelling. A 2,500-gallon cistern in the basement collected rainwater for the use of the keeper and his family, and a privy hung over the outside deck.

Right: Poplar Point Light and Wickford Harbor Light From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The lighthouse superstructure was an eight-room wood-frame Gothic Revival house much like the one constructed a few years later at the northern tip of Conanicut Island. A square lighthouse tower was attached to a corner of the dwelling. A 2,500-gallon cistern in the basement collected rainwater for the use of the keeper and his family, and a privy hung over the outside deck.

A fifth-order Fresnel lens, showing a fixed white light 52 feet above the water, was first illuminated on November 1, 1882.

The old light at Poplar Point was simultaneously discontinued. A fog bell and striking machinery were also installed.

There were only three keepers of Wickford Light in its 48 years of service. They were Henry F. Sherman (1882-1886), Nathaniel Dodge (1886-1893), and Edmund Andrews. Henry Sherman had been the keeper of Poplar Point Light since 1874.

A strange story has been passed down concerning one of this light’s keepers. One version of the story is found in an undated, yellowed newspaper clipping of unknown origin in this author’s collection. The name attributed to the keeper in the article is Peter Phillips. There was never a keeper here by that name, but it’s possible that the writer thought it prudent not to use actual names.

According to the article, Keeper Phillips “would be drunk for weeks at a time.” His alcoholism took an unusual form. It seems that the keeper was an “essence addict,” preferring vanilla and lemon extract to beer or whiskey. The keeper's wife was described as too obese to do the work, so Phillips’s 18-year-old daughter, Ann, performed most of the actual keeper’s duties, with the help of her younger sister, Betty.

There were only three keepers of Wickford Light in its 48 years of service. They were Henry F. Sherman (1882-1886), Nathaniel Dodge (1886-1893), and Edmund Andrews. Henry Sherman had been the keeper of Poplar Point Light since 1874.

A strange story has been passed down concerning one of this light’s keepers. One version of the story is found in an undated, yellowed newspaper clipping of unknown origin in this author’s collection. The name attributed to the keeper in the article is Peter Phillips. There was never a keeper here by that name, but it’s possible that the writer thought it prudent not to use actual names.

According to the article, Keeper Phillips “would be drunk for weeks at a time.” His alcoholism took an unusual form. It seems that the keeper was an “essence addict,” preferring vanilla and lemon extract to beer or whiskey. The keeper's wife was described as too obese to do the work, so Phillips’s 18-year-old daughter, Ann, performed most of the actual keeper’s duties, with the help of her younger sister, Betty.

Young Ann soon struck up a romance with a local fisherman called “Nat Perry” in the article. Nat asked Ann to marry him, but her hesitation to leave the lighthouse in the care of her younger sister caused Nat to break off their relationship and marry his former sweetheart instead.

The turn of events caused Ann to faint, and she remained unconscious for three days. In the midst of all this, an inspector arrived to find the lighthouse in disarray, and Keeper Phillips was fired. Ann never got out of bed for the next 40 years, goes the story.

The writer, identified as “A. H.,” knew Ann in later years and helped get her into a nursing home. Ann had died by the time A. H. wrote, “When I am down Wickford way, I often stay awake at night watching that spurt of green from the lighthouse because it reminds me of the story of Ann. And over and over I try to imagine how the pale, bedridden woman I knew looked as a girl of 18 on that night she had to decide.”

An almost identical version of this story is found in the 1985 book Wickford Anthology, edited by Peter Clarkson Crolius. The chief difference is that in this version, the keeper is identified as “Peter Sherman,” and his daughters as Jessie and Sarah. Whether the story is more or less true and involved the family of Keeper Henry Sherman is impossible to determine at this late date. In any case, in October 1885, Nathaniel Dodge succeeded Sherman as keeper.

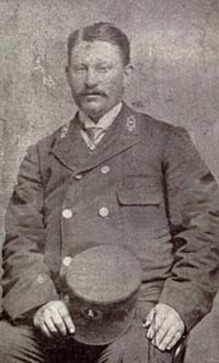

Right: Keeper Edmund Andrews (1868-1939) Photo courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

The writer, identified as “A. H.,” knew Ann in later years and helped get her into a nursing home. Ann had died by the time A. H. wrote, “When I am down Wickford way, I often stay awake at night watching that spurt of green from the lighthouse because it reminds me of the story of Ann. And over and over I try to imagine how the pale, bedridden woman I knew looked as a girl of 18 on that night she had to decide.”

An almost identical version of this story is found in the 1985 book Wickford Anthology, edited by Peter Clarkson Crolius. The chief difference is that in this version, the keeper is identified as “Peter Sherman,” and his daughters as Jessie and Sarah. Whether the story is more or less true and involved the family of Keeper Henry Sherman is impossible to determine at this late date. In any case, in October 1885, Nathaniel Dodge succeeded Sherman as keeper.

Right: Keeper Edmund Andrews (1868-1939) Photo courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

Keeper Edmund (his name was often reported as Edward) Andrews, who came to Wickford in 1893, was born in 1868 in Providence. He was the son of an English carpenter and an Irishwoman.

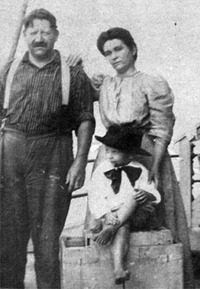

Andrews went to sea aboard the George W. Darrison out of Block Island, and by 1891 he was working as an assistant lighthouse keeper at Whale Rock Light. While in that position Andrews married Lillian A. Sprague, 17, of Block Island.

Left: Keeper Edmund Andrews and family on the ice outside the lighthouse. Courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

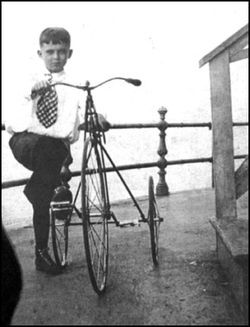

Andrews eventually became the head keeper at Whale Rock. Edmund and Lillian had one child when they moved to Wickford, and three more children were born at the lighthouse during their years there. The children made the most of their waterbound home. Their son, Edward, later said that his knuckles were frequently banged up from riding his bicycle in circles around the lighthouse, bumping into the iron railings that surrounded it.

Left: Keeper Edmund Andrews and family on the ice outside the lighthouse. Courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

Andrews eventually became the head keeper at Whale Rock. Edmund and Lillian had one child when they moved to Wickford, and three more children were born at the lighthouse during their years there. The children made the most of their waterbound home. Their son, Edward, later said that his knuckles were frequently banged up from riding his bicycle in circles around the lighthouse, bumping into the iron railings that surrounded it.

Keeper Andrews was recognized for the rescue of a drowning man in 1898, and a 1905 inspection showed the station in “excellent order.” There were to be some rough times, however.

In 1907, Andrews was accused of stealing a neighbor’s chickens (he was later cleared), and was reprimanded for housing his brother-in-law and a friend at the station. The keeper pointed out in his defense that he had been ill and that his wife’s brother was there to row the family’s children ashore to school each day. The friend who had been staying at the lighthouse was a keeper of Block Island North Light. Andrews was told that he would have been allowed to have another person at the station if he was ill.

Right, Edward Andrews with his bicycle on the lighthouse deck. Courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

In 1909, Keeper Andrews was offered a transfer to Eatons Neck Light on Long Island, New York. He turned down this transfer, saying, “I would like to have a land station where there is no vapor lamp or an assistant keeper, not too far out of Rhode Island.” His request was never granted. Keeper Andrews spent the rest of his long lightkeeping career at Wickford Harbor.

Keeper Andrews was reprimanded in 1918 for the subpar condition of the station, but no action was taken as officials recognized that the keeper’s wife had been ill. It appears that the situation had improved by 1927, when Andrews was commended for the excellent condition of the site. In June 1930, Andrews requested a retirement with a pension, saying he suffered from “heart trouble and stomach trouble.” He retired after 40 years of service in 1930 and was granted a pension of $969.66 yearly.

Right, Edward Andrews with his bicycle on the lighthouse deck. Courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

In 1909, Keeper Andrews was offered a transfer to Eatons Neck Light on Long Island, New York. He turned down this transfer, saying, “I would like to have a land station where there is no vapor lamp or an assistant keeper, not too far out of Rhode Island.” His request was never granted. Keeper Andrews spent the rest of his long lightkeeping career at Wickford Harbor.

Keeper Andrews was reprimanded in 1918 for the subpar condition of the station, but no action was taken as officials recognized that the keeper’s wife had been ill. It appears that the situation had improved by 1927, when Andrews was commended for the excellent condition of the site. In June 1930, Andrews requested a retirement with a pension, saying he suffered from “heart trouble and stomach trouble.” He retired after 40 years of service in 1930 and was granted a pension of $969.66 yearly.

A medical exam recorded that Andrews had been suffering from heart disease, rheumatism, and a nervous tremor, among other ailments.

He died in Massachusetts at the Chelsea Naval Hospital in 1939, the year the Lighthouse Service was taken over by the U.S. Coast Guard.

The lighthouse was destroyed in 1930. As a cost-saving measure, it was replaced by a small, unmanned, automatic light. Today, a square skeleton tower showing a flashing green light tops a pile of rocks on the old lighthouse site.

Left: Keeper Edmund Andrews, his wife Lillian and son Harry Franklin Andrews. Circa 1912. Photo courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

The lighthouse was destroyed in 1930. As a cost-saving measure, it was replaced by a small, unmanned, automatic light. Today, a square skeleton tower showing a flashing green light tops a pile of rocks on the old lighthouse site.

Left: Keeper Edmund Andrews, his wife Lillian and son Harry Franklin Andrews. Circa 1912. Photo courtesy of Jo Ann Tarbox

Keepers: Henry F. Sherman (1882-1885), Nathaniel Dodge (1885-1893), Edmund Andrews (1893-1930)