History of Boston Light, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Boston Light, aptly dubbed the “ideal American lighthouse” by the historian Edward Rowe Snow, holds a place of honor among our nation’s beacons. This was the first light station established on the North American continent, and the last in the United States to be automated. It’s also our only light station that still retains an official keeper.

Seasonal public tours provide the public with the opportunity to experience this cultural treasure up close, and few attractions in New England can approach the thrilling panorama of the harbor and city seen from the lighthouse’s lantern.

There were simple lighted beacons in the harbor before the first lighthouse. The primary function of the early beacons was not navigational, but rather to warn of approaching enemy vessels. It’s recorded that there was a beacon on Point Allerton in Hull as early as 1673. The beacon was a simple structure supporting an open iron basket or grate in which “fier-bales of pitch and ocre” were burned.

There were simple lighted beacons in the harbor before the first lighthouse. The primary function of the early beacons was not navigational, but rather to warn of approaching enemy vessels. It’s recorded that there was a beacon on Point Allerton in Hull as early as 1673. The beacon was a simple structure supporting an open iron basket or grate in which “fier-bales of pitch and ocre” were burned.

There may have been an unlighted day beacon on the island we now know as Little Brewster before the lighthouse was established there. Early records refer to it as “Beacon Island.”

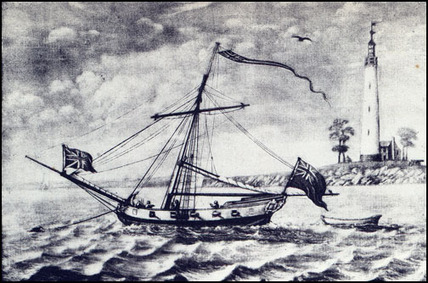

1729 engraving

The rocky island—about a mile north of Hull and about 8 eight miles east of Boston—is only about 600 feet long with a maximum widthand at most of 250 feet wide, with a total area of only one acre above the mean high water mark. The highest elevation of about 18 feet is at the eastern end of the island, where the lighthouse is located.

Boston’s deep and spacious harbor led it to become the commercial center of America in colonial days. At that time, all large vessels had to enter the harbor between the Brewster Islands in the outer harbor and Point Allerton in the town of Hull. Clough’s New England Almanac of 1701 hinted at the need for a lighthouse at the entrance to the harbor. Early in 1713, a prominent Boston merchant and selectman named John George, representing the business community of the city proposed to the General Court the “Erecting of a Light Hous & Lanthorn on some Head Land at the Entrance to the Harbour of Boston for the Direction of Ships & Vessels in the Night Time bound into the said Harbour.”

A committee headed by Lieutenant Governor William Tailer planned for the lighthouse. After visiting several of the harbor islands and conferring with the area’s most experienced shipmasters, Tailer reported that the best site for the lighthouse was “the Southernmost Part of the Great Brewster called Beacon Island.” Several islands in Boston’s outer harbor are collectively known as the Brewsters, after the Elder Brewster of the Plymouth Colony. Beacon Island, now known as Little Brewster, is attached to Great Brewster by a sand bar.

On July 23, 1715, the General Court of Massachusetts passed the Boston Light Bill. It read, in part:

Whereas the want of a lighthouse erected at the entrance to the harbor of Boston hath been a great discouragement to navigation by the loss of the lives and estates of several of his majesty's subjects; for prevention thereof -- Be it enacted...that there be a lighthouse erected at the charge of the Province, on the southernmost part of the Great Brewster, called Beacon Island, to be kept lighted from sun setting to sun rising.

The first lighthouse was financed by a tax of a penny a ton on all vessels coming into the harbor, and the same amount for vessels leaving the harbor. Smaller coasting vessels paid only two shillings as they left the harbor. Fishing vessels and small vessels transporting lumber and other building materials locally were taxed five shillings yearly.

A stone tower was built at a cost of £2,385. The exact dimensions aren’t known, but it’s believed the tower was at least 50 feet tall. The first keeper, 43-year-old George Worthylake, lighted the lighthouse on Friday, September 14, 1716. No description of the original lighting apparatus survives, but Arnold Burges Johnson wrote in his book The Modern Light-House Service that it was “first lighted by tallow candles.” The keeper was supplied with “Oyl Week and Candles” in November 1716; it’s possible that the lantern originally held both candles and oil lamps.

Boston’s deep and spacious harbor led it to become the commercial center of America in colonial days. At that time, all large vessels had to enter the harbor between the Brewster Islands in the outer harbor and Point Allerton in the town of Hull. Clough’s New England Almanac of 1701 hinted at the need for a lighthouse at the entrance to the harbor. Early in 1713, a prominent Boston merchant and selectman named John George, representing the business community of the city proposed to the General Court the “Erecting of a Light Hous & Lanthorn on some Head Land at the Entrance to the Harbour of Boston for the Direction of Ships & Vessels in the Night Time bound into the said Harbour.”

A committee headed by Lieutenant Governor William Tailer planned for the lighthouse. After visiting several of the harbor islands and conferring with the area’s most experienced shipmasters, Tailer reported that the best site for the lighthouse was “the Southernmost Part of the Great Brewster called Beacon Island.” Several islands in Boston’s outer harbor are collectively known as the Brewsters, after the Elder Brewster of the Plymouth Colony. Beacon Island, now known as Little Brewster, is attached to Great Brewster by a sand bar.

On July 23, 1715, the General Court of Massachusetts passed the Boston Light Bill. It read, in part:

Whereas the want of a lighthouse erected at the entrance to the harbor of Boston hath been a great discouragement to navigation by the loss of the lives and estates of several of his majesty's subjects; for prevention thereof -- Be it enacted...that there be a lighthouse erected at the charge of the Province, on the southernmost part of the Great Brewster, called Beacon Island, to be kept lighted from sun setting to sun rising.

The first lighthouse was financed by a tax of a penny a ton on all vessels coming into the harbor, and the same amount for vessels leaving the harbor. Smaller coasting vessels paid only two shillings as they left the harbor. Fishing vessels and small vessels transporting lumber and other building materials locally were taxed five shillings yearly.

A stone tower was built at a cost of £2,385. The exact dimensions aren’t known, but it’s believed the tower was at least 50 feet tall. The first keeper, 43-year-old George Worthylake, lighted the lighthouse on Friday, September 14, 1716. No description of the original lighting apparatus survives, but Arnold Burges Johnson wrote in his book The Modern Light-House Service that it was “first lighted by tallow candles.” The keeper was supplied with “Oyl Week and Candles” in November 1716; it’s possible that the lantern originally held both candles and oil lamps.

Worthylake, who was brought up on George’s Island (previously known as Pemberton Island) in Boston Harbor, moved to the light station with his wife, Ann. They had five children, and it appears that their daughters Ruth and Ann lived at the lighthouse with them. Two African slaves named Shadwell and Dina also lived with the Worthylakes, and also a servant by the name of George Cutler.

The triple gravestone of George, Ann, and Ruth Worthylake in Boston

Worthylake also maintained a farm on Lovell’s Island, closer to Boston.Worthylake was paid £50 a year, which was raised to £75 in 1717. He made additional money as a harbor pilot for incoming vessels, and he also kept a flock of sheep on Great Brewster Island.

Fifty-nine of his sheep were caught on the long sand spit off Great Brewster during a 1717 storm; they drowned when the tide came in.

In early November 1718, Worthylake went to Boston with his wife and their 15-year-old daughter Ruth. They reportedly attended church in Boston on Sunday, November 2. Some sources indicate that Worthylake also picked up his pay during the visit to the city; in any case, they left to return to Boston Light on Monday morning, November 3.

On their way back they stopped at Lovell’s Island, where Worthylake and his wife and daughter boarded a sloop heading for Boston Light. A friend, John Edge, accompanied them. Witnesses later said that the party were seen to eat and drink “very friendly” while aboard the sloop, “tho not to excess.”

The sloop anchored near Little Brewster Island a little few minutes past noon, and the slave Shadwell paddled out in a canoe to transfer the party to the island. Young Ann Worthylake and a friend, Mary Thompson, watched from shore. Suddenly, the two girls on shore saw “Worthylake, his wife & others swimming or floating on the water, with their boat Oversett.” The canoe—possibly overloaded—had capsized, and all six people (including the servant, George Cutler) drowned. George, Ann, and Ruth Worthylake were buried beneath a triple headstone in the Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in Boston’s North End. The Worthylakes' daughter Ann soon married a stonecutter named John Gaud, who may have carved the triple gravestone at Copp's Hill.

Fifty-nine of his sheep were caught on the long sand spit off Great Brewster during a 1717 storm; they drowned when the tide came in.

In early November 1718, Worthylake went to Boston with his wife and their 15-year-old daughter Ruth. They reportedly attended church in Boston on Sunday, November 2. Some sources indicate that Worthylake also picked up his pay during the visit to the city; in any case, they left to return to Boston Light on Monday morning, November 3.

On their way back they stopped at Lovell’s Island, where Worthylake and his wife and daughter boarded a sloop heading for Boston Light. A friend, John Edge, accompanied them. Witnesses later said that the party were seen to eat and drink “very friendly” while aboard the sloop, “tho not to excess.”

The sloop anchored near Little Brewster Island a little few minutes past noon, and the slave Shadwell paddled out in a canoe to transfer the party to the island. Young Ann Worthylake and a friend, Mary Thompson, watched from shore. Suddenly, the two girls on shore saw “Worthylake, his wife & others swimming or floating on the water, with their boat Oversett.” The canoe—possibly overloaded—had capsized, and all six people (including the servant, George Cutler) drowned. George, Ann, and Ruth Worthylake were buried beneath a triple headstone in the Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in Boston’s North End. The Worthylakes' daughter Ann soon married a stonecutter named John Gaud, who may have carved the triple gravestone at Copp's Hill.

Benjamin Franklin, 12 years old at the time, was urged by his brother to write a poem based on the disaster. The young Franklin wrote a poem called The Lighthouse Tragedy and hawked copies on the streets of Boston. Franklin later wrote in his autobiography that the poem was “wretched stuff,” although it “sold prodigiously.”

Robert Saunders, a former sloop captain, became Boston Light’s second keeper on a temporary basis, until a new permanent keeper could be chosen. Saunders died only a few days after taking the job. He and another man drowned when their boat capsized on their way back to the island after they had boarded an inbound ship.

John Hayes, an experienced seaman described as an “able-bodied and discreet person,” became the next keeper.

Hayes asked for a gallery to be installed around the tower’s lantern room so that he could clean the glass of ice and snow. He also noted the need for some kind of fog signal, asking that “a great Gun may be placed on the Said Island to answer Ships in a Fogg.”

John Hayes, an experienced seaman described as an “able-bodied and discreet person,” became the next keeper.

Hayes asked for a gallery to be installed around the tower’s lantern room so that he could clean the glass of ice and snow. He also noted the need for some kind of fog signal, asking that “a great Gun may be placed on the Said Island to answer Ships in a Fogg.”

A cannon (above right), America’s first fog signal, was placed on the island in 1719. Passing ships would fire their cannons when passing nearby in times of fog, and the keeper would reply with a blast from the light station. The cannon, cast in 1700 and possibly relocated from Long Island in the inner harbor, served on Little Brewster Island for 132 years.

In the early 1960s, the cannon was moved to the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. In 1993, it was returned by helicopter to Little Brewster, and today the venerable fog cannon sits today on a new carriage inside the base of the lighthouse tower (left).

A fire broke out in the lighthouse lantern on January 13, 1720, caused by the oil lamps falling on wooden benches. Hayes’s wife roused the keeper in the evening and informed him of the fire, and Hayes quickly ran up the stairs of the tower with two pails of water. He later reported that the “fire was too violent to be subdued,” but he “saved many things belonging to the Light House.”

A fire broke out in the lighthouse lantern on January 13, 1720, caused by the oil lamps falling on wooden benches. Hayes’s wife roused the keeper in the evening and informed him of the fire, and Hayes quickly ran up the stairs of the tower with two pails of water. He later reported that the “fire was too violent to be subdued,” but he “saved many things belonging to the Light House.”

John Hayes retired because of advancing age in 1733. Robert Ball, an Englishman whose stay of about 40 years would be the longest stint of any keeper in the station’s history, succeeded him. Ball was assisted by a slave known as Samson, who died in 1762 and was buried on Rainsford Island in the harbor.

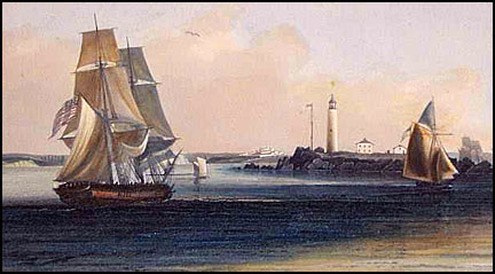

C. early 1780s, from a painting by Capt. Matthew Parke. This image apparently depicts the original tower before its 1776 destruction.

The keeper still doubled as a harbor pilot during Ball’s stay. Ball seems to have made out well financially; he eventually owned three of the harbor islands—Outer Brewster, Calf Island, and Green Island.A bad fire gutted the lighthouse in 1751, and for a time the light was shown from a 40-foot spar. The early lighthouse was struck by lightning on several occasions, including an instance in June 1754 when lightning "tore off shingles from several places on the outside." The installation of a lightning rod was delayed because of the objections of some "godly men" who thought it "vanity and irreligion for the arm of flesh to presume to avert the stroke of heaven," according to a 1789 article. Practicality eventually won out and a lightning conductor was installed.

More repairs to the lighthouse were in the works when the American Revolution intervened. In July 1775, Boston Harbor and the lighthouse were under the control of the British. On July 20, American troops under Major Joseph Vose landed at the lighthouse and took lamps, oil, and some gunpowder, and burned the wooden parts of the tower. After leaving the island they had to outrun an armed British schooner, and two Americans were wounded. An eyewitness described “the flames of the lighthouse ascending up to Heaven, like grateful incense, and the ships wasting their powder.”

As the British worked to repair the tower, 300 American soldiers under Major Benjamin Tupper landed at the island on July 31. They easily defeated the British guard and again burned the lighthouse. As they tried to leave, they found their boats stranded as, for the tide had gone out. This gave British vessels time to reach the scene.

The Americans finally managed to launch their boats as the British fired on them. American troops at Nantasket in Hull helped by firing a cannon at the British boats, landing a direct hit on one. This turned the tide of battle and the Americans escaped with only one soldier having been killed. General George Washington praised the men: “The General thanks Major Tupper and the Officers and Soldiers under his Command, for their gallant and soldierlike behaviour in possessing themselves of the enemy’s post at the Light House, and for the Number of Prisoners they took there, and doubts not, but the Continental Army, will be as famous for their mercy as for their valour.”

At the end of their occupation of Boston Harbor during the war, the British lingered in the harbor for some months. As they left the area on June 13, 1776, one of their final acts was to set off a timed charge on the lighthouse island, completely destroying the tower. The remains of the metal lantern were used to make ladles for American cannons.

According to some sources, Keeper Robert Ball (whose nephew, William Minns, had served as keeper from some time in 1774 until July 1775) sailed away with the British fleet to Halifax in 1776, never to be seen in Boston Harbor again. But according to an October 1895 article in New England Magazine, after the destruction of the lighthouse in June 1776, Ball was certified by the Boston Committee of Correspondence as a person “friendly to the Rights and Liberties of Americans.”

In June 1783, a committee of the Boston Marine Society addressed the lack of a lighthouse. The commissary general of Massachusetts, Richard Devens, was authorized to build a new lighthouse on the original site. The new 60-foot (75 feet to the top of the octagonal lantern), conical rubblestone tower was designed to be “nearly of the same dimensions of the former lighthouse.” It has been claimed that part of the original tower was incorporated into the new one, and recent restoration work has revealed that the stone work near the bottom of the tower is quite different than the upper part of the tower, which would seem to support that theory.

Thomas Knox was the first post-Revolution keeper. He stayed in the position for 27 years, also serving as a harbor pilot. Two of his brothers were also harbor pilots. Knox’s father owned Nix’s Mate Island in the harbor, and Thomas inherited ownership when his father died in 1790.

The light station was ceded to the federal government in 1790. With the change, Knox lost his title as Boston’s official “branch pilot.” Governor John Hancock assigned that designation to another man, but Knox continued to work as a pilot.

More repairs to the lighthouse were in the works when the American Revolution intervened. In July 1775, Boston Harbor and the lighthouse were under the control of the British. On July 20, American troops under Major Joseph Vose landed at the lighthouse and took lamps, oil, and some gunpowder, and burned the wooden parts of the tower. After leaving the island they had to outrun an armed British schooner, and two Americans were wounded. An eyewitness described “the flames of the lighthouse ascending up to Heaven, like grateful incense, and the ships wasting their powder.”

As the British worked to repair the tower, 300 American soldiers under Major Benjamin Tupper landed at the island on July 31. They easily defeated the British guard and again burned the lighthouse. As they tried to leave, they found their boats stranded as, for the tide had gone out. This gave British vessels time to reach the scene.

The Americans finally managed to launch their boats as the British fired on them. American troops at Nantasket in Hull helped by firing a cannon at the British boats, landing a direct hit on one. This turned the tide of battle and the Americans escaped with only one soldier having been killed. General George Washington praised the men: “The General thanks Major Tupper and the Officers and Soldiers under his Command, for their gallant and soldierlike behaviour in possessing themselves of the enemy’s post at the Light House, and for the Number of Prisoners they took there, and doubts not, but the Continental Army, will be as famous for their mercy as for their valour.”

At the end of their occupation of Boston Harbor during the war, the British lingered in the harbor for some months. As they left the area on June 13, 1776, one of their final acts was to set off a timed charge on the lighthouse island, completely destroying the tower. The remains of the metal lantern were used to make ladles for American cannons.

According to some sources, Keeper Robert Ball (whose nephew, William Minns, had served as keeper from some time in 1774 until July 1775) sailed away with the British fleet to Halifax in 1776, never to be seen in Boston Harbor again. But according to an October 1895 article in New England Magazine, after the destruction of the lighthouse in June 1776, Ball was certified by the Boston Committee of Correspondence as a person “friendly to the Rights and Liberties of Americans.”

In June 1783, a committee of the Boston Marine Society addressed the lack of a lighthouse. The commissary general of Massachusetts, Richard Devens, was authorized to build a new lighthouse on the original site. The new 60-foot (75 feet to the top of the octagonal lantern), conical rubblestone tower was designed to be “nearly of the same dimensions of the former lighthouse.” It has been claimed that part of the original tower was incorporated into the new one, and recent restoration work has revealed that the stone work near the bottom of the tower is quite different than the upper part of the tower, which would seem to support that theory.

Thomas Knox was the first post-Revolution keeper. He stayed in the position for 27 years, also serving as a harbor pilot. Two of his brothers were also harbor pilots. Knox’s father owned Nix’s Mate Island in the harbor, and Thomas inherited ownership when his father died in 1790.

The light station was ceded to the federal government in 1790. With the change, Knox lost his title as Boston’s official “branch pilot.” Governor John Hancock assigned that designation to another man, but Knox continued to work as a pilot.

In 1794, Knox’s yearly salary as keeper was set by the federal government at $266.67, which was raised to $333.33 in 1796.

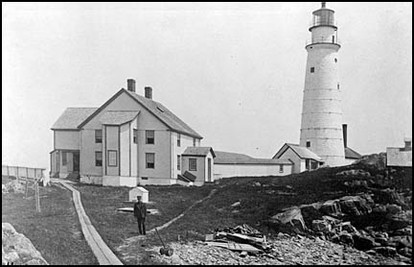

Boston Light and the 1859 duplex keeper's house

In an article published in 1789, Knox described the lighting apparatus as four lamps, each holding a gallon of oil, and each having four lights. The lamps were divided into four sections, with each section operating independently.

There were complaints that the light was too dim when seen from the sea, and the lamps produced a great deal of smoke.

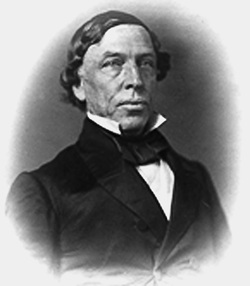

In 1807, Winslow Lewis, a member of the Boston Marine Society, began experiments with lighthouse illumination. He patented his system of Argand lamps (more efficient and less smoky than the old lamps) paired with parabolic reflectors in 1810. He first demonstrated his system in the cupola of the State House in Boston.

There were complaints that the light was too dim when seen from the sea, and the lamps produced a great deal of smoke.

In 1807, Winslow Lewis, a member of the Boston Marine Society, began experiments with lighthouse illumination. He patented his system of Argand lamps (more efficient and less smoky than the old lamps) paired with parabolic reflectors in 1810. He first demonstrated his system in the cupola of the State House in Boston.

Lewis’s system was subsequently installed at Boston Light in May 1810. Six whale oil–fueled Argand lamps were installed in two parallel rows, about 15 inches apart. A parabolic reflector was placed behind each lamp.

Winslow Lewis

An observer on a vessel about nine miles from both Boston Light and the light station at Baker’s Island reported:

The difference in the brightness of these and the Light at Baker’s island was as great as would appear between a well trimmed Argand lamp and a common Candle. . . . At 11 o’clock these were extinguished and the common lamps relighted—the effect produced by the change from light to comparative darkness was more striking than the first. We now stood towards the Lighthouse. At 12 o’clock the Argand Lamps were again lighted . . . When within two and an half leagues their power was so great as to throw a strong Shadow on the deck of the Vessel.

The Boston Marine Society urged the adoption of Lewis’s apparatus in all American lighthouses, and he was subsequently awarded a contract for that purpose. The Lewis system remained in use into the 1850s, long after much of the rest of the world had adopted the use of the more efficient Fresnel lens invented in France in 1822.

In June 1809, the local lighthouse superintendent, Henry Dearborn, found three perpendicular cracks in the tower, extending for almost its entire height. Six iron hoops were added around the tower for extra support. One band was removed in the early twentieth century; five aluminum bands are in place today.

Jonathan Bruce followed Knox as keeper in 1811, but surviving correspondence indicates that Knox remained living in a dwelling on the island for some time. Bruce and his wife, Lydia, watched from the island on June 1, 1813, as the British ship Shannon battled the American frigate Chesapeake during the War of 1812. The Chesapeake was swiftly defeated, but not before the mortally wounded Captain James Lawrence uttered the immortal words, “Don’t give up the ship!” Bruce's wife, Lydia, died in the keeper's house in 1828. Bruce left Boston Light in 1833 and moved to Rainsford Island in Boston Harbor.

Lieutenant Edward W. Carpender inspected the station in 1838, while David Tower was the keeper. Tower complained that the lantern leaked, which sometimes caused the rotating mechanism to stop and forced him to turn the apparatus by hand. Like his predecessors, Tower doubled as a harbor pilot. Carpender noted that this practice took Tower away from the lighthouse frequently at night, and he recommended that keepers be forbidden by law to take on any pursuits that removed them from their station during the hours that they should be concerned, above all, with the lighting of the lamps.

Winslow Lewis installed a new lantern in 1839, along with new 21-inch reflectors from England. The engineer I. W. P. Lewis, Winslow's nephew, visited Boston Light for his 1843 report to Congress. He was critical, calling the tower "loose and leaky," and noting that the wooden stairway was so rotten "as to be unsafe of ascent." The two-story house, with four rooms on each floor, was in good repair, as was a new boathouse.

David Tower died in 1844 after a brief illness. That same year, a new cast-iron spiral stairway with a wrought-iron railing was installed; the stairway is still in use today. Iron doors and window frames were also installed.

Joshua Snow followed Tower as keeper. Around this time, an unusual enterprise was in operation on Little Brewster Island—a “Spanish cigar factory,” staffed by young girls from Boston. The cigars the girls made were labeled as “Cuban” and were sold to unsuspecting locals. The authorities soon broke up the illegal business. Some sources place the cigar factory during the tenure of the next keeper, but it seems more likely that it operated during Snow’s stay. Snow left in December 1844, apparently dismissed after only a few months on the island.

Tobias Cook of Cohasset, Massachusetts, was the next keeper, staying until 1849. Following Cook as keeper was William Long of Charlestown, Massachusetts.

A 1,375-pound fog bell, operated by clockwork machinery, replaced the old cannon in 1851. An 1851 inspection was somewhat critical of Long, noting that he didn’t light up at sunset or put out the light precisely at sunrise. The tower was in need of whitewashing, and the copper lightning conductors were broken and neglected by the keeper.

A Gloucester native, Moses Barrett, saw much change during his time as keeper (1856–62). The Lighthouse Board had suggested in 1857 that the tower be rebuilt at a cost of $71,000, but improvements were made instead. In 1859, the tower was raised to its present height of 89 feet and a new lantern was installed along with a 12-sided, second-order Fresnel lens. The giant lens—about 11 feet tall and 15 feet in circumference—rotated by means of a clockwork mechanism that required frequent winding. A single lamp inside the new lens replaced the system of multiple lamps, and round “"bull’s-eye”" panels on the lens produced a flash each time they passed in front of the light source. The lens went into operation on December 20, 1859.

In the same year, the tower was lined with brick, a spacious brick entryway was added to the tower, and a new duplex keeper’s house was built. Beginning in 1861, Boston Light was assigned a keeper and two assistants.

The difference in the brightness of these and the Light at Baker’s island was as great as would appear between a well trimmed Argand lamp and a common Candle. . . . At 11 o’clock these were extinguished and the common lamps relighted—the effect produced by the change from light to comparative darkness was more striking than the first. We now stood towards the Lighthouse. At 12 o’clock the Argand Lamps were again lighted . . . When within two and an half leagues their power was so great as to throw a strong Shadow on the deck of the Vessel.

The Boston Marine Society urged the adoption of Lewis’s apparatus in all American lighthouses, and he was subsequently awarded a contract for that purpose. The Lewis system remained in use into the 1850s, long after much of the rest of the world had adopted the use of the more efficient Fresnel lens invented in France in 1822.

In June 1809, the local lighthouse superintendent, Henry Dearborn, found three perpendicular cracks in the tower, extending for almost its entire height. Six iron hoops were added around the tower for extra support. One band was removed in the early twentieth century; five aluminum bands are in place today.

Jonathan Bruce followed Knox as keeper in 1811, but surviving correspondence indicates that Knox remained living in a dwelling on the island for some time. Bruce and his wife, Lydia, watched from the island on June 1, 1813, as the British ship Shannon battled the American frigate Chesapeake during the War of 1812. The Chesapeake was swiftly defeated, but not before the mortally wounded Captain James Lawrence uttered the immortal words, “Don’t give up the ship!” Bruce's wife, Lydia, died in the keeper's house in 1828. Bruce left Boston Light in 1833 and moved to Rainsford Island in Boston Harbor.

Lieutenant Edward W. Carpender inspected the station in 1838, while David Tower was the keeper. Tower complained that the lantern leaked, which sometimes caused the rotating mechanism to stop and forced him to turn the apparatus by hand. Like his predecessors, Tower doubled as a harbor pilot. Carpender noted that this practice took Tower away from the lighthouse frequently at night, and he recommended that keepers be forbidden by law to take on any pursuits that removed them from their station during the hours that they should be concerned, above all, with the lighting of the lamps.

Winslow Lewis installed a new lantern in 1839, along with new 21-inch reflectors from England. The engineer I. W. P. Lewis, Winslow's nephew, visited Boston Light for his 1843 report to Congress. He was critical, calling the tower "loose and leaky," and noting that the wooden stairway was so rotten "as to be unsafe of ascent." The two-story house, with four rooms on each floor, was in good repair, as was a new boathouse.

David Tower died in 1844 after a brief illness. That same year, a new cast-iron spiral stairway with a wrought-iron railing was installed; the stairway is still in use today. Iron doors and window frames were also installed.

Joshua Snow followed Tower as keeper. Around this time, an unusual enterprise was in operation on Little Brewster Island—a “Spanish cigar factory,” staffed by young girls from Boston. The cigars the girls made were labeled as “Cuban” and were sold to unsuspecting locals. The authorities soon broke up the illegal business. Some sources place the cigar factory during the tenure of the next keeper, but it seems more likely that it operated during Snow’s stay. Snow left in December 1844, apparently dismissed after only a few months on the island.

Tobias Cook of Cohasset, Massachusetts, was the next keeper, staying until 1849. Following Cook as keeper was William Long of Charlestown, Massachusetts.

A 1,375-pound fog bell, operated by clockwork machinery, replaced the old cannon in 1851. An 1851 inspection was somewhat critical of Long, noting that he didn’t light up at sunset or put out the light precisely at sunrise. The tower was in need of whitewashing, and the copper lightning conductors were broken and neglected by the keeper.

A Gloucester native, Moses Barrett, saw much change during his time as keeper (1856–62). The Lighthouse Board had suggested in 1857 that the tower be rebuilt at a cost of $71,000, but improvements were made instead. In 1859, the tower was raised to its present height of 89 feet and a new lantern was installed along with a 12-sided, second-order Fresnel lens. The giant lens—about 11 feet tall and 15 feet in circumference—rotated by means of a clockwork mechanism that required frequent winding. A single lamp inside the new lens replaced the system of multiple lamps, and round “"bull’s-eye”" panels on the lens produced a flash each time they passed in front of the light source. The lens went into operation on December 20, 1859.

In the same year, the tower was lined with brick, a spacious brick entryway was added to the tower, and a new duplex keeper’s house was built. Beginning in 1861, Boston Light was assigned a keeper and two assistants.

Charles E. Blair, keeper from 1862 to 1864, witnessed Confederate prisoners being transported to Boston Harbor’s Fort Warren, which served as a prison during the Civil War. The next keeper, Thomas Bates, took over in July 1864 and remained until his death in April 1893.

Thomas Bates

The light station was the scene of many happy gatherings during the Bates era. Frequent singalongs took place, with the accompaniment of assistant keeper Edward Gorham on accordion. When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder and Crossing the Bar were special favorites.

On January 31, 1882, Keeper Bates, along with an assistant and a local fisherman, rescued the crew of the Fanny Pike, which had run into Shag Rocks.

A brick cistern was added in 1884 in a building near the tower. The cistern held 21,800 gallons of rainwater for the keepers and their families. A second keeper’s house was added in 1885, located at the opposite end of the island from the lighthouse. Two houses had become a necessity with three keepers and their families living on the island with their families.

On January 31, 1882, Keeper Bates, along with an assistant and a local fisherman, rescued the crew of the Fanny Pike, which had run into Shag Rocks.

A brick cistern was added in 1884 in a building near the tower. The cistern held 21,800 gallons of rainwater for the keepers and their families. A second keeper’s house was added in 1885, located at the opposite end of the island from the lighthouse. Two houses had become a necessity with three keepers and their families living on the island with their families.

A Daboll compressed- air fog trumpet replaced the bell in 1872. It remained in use until 1887, when a steam-driven siren replaced it. In the late nineteenth century, students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology conducted experiments with fog signals at Boston Light, trying to perfect a signal that would penetrate the so-called “ghost walk,” an area about six miles east of the lighthouse where no sound could penetrate.

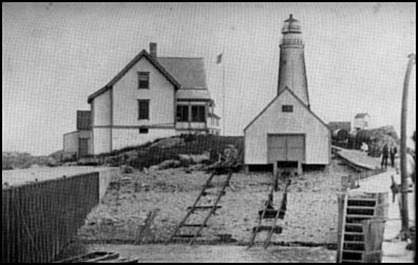

Late nineteenth century view, courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard

Despite the students’ best efforts, even the largest horn could not penetrate the ghost walk.

Alfred M. Horte had a brief stay as keeper after the death of Bates. Henry L. Pingree was keeper from 1894 to 1909. Pingree’s son, Wesley, who was an assistant keeper at Deer Island Light in Boston Harbor, married Horte’s sister, Josephine.

An auxiliary light was added to the station in 1890—a fixed white light exhibited from a small wooden building. The light was designed to help mariners avoid dangerous Harding’s Ledge. If they strayed too far from the channel to either side, a red light was seen.

The next keeper, Levi B. Clark, weathered a tremendous blizzard on Christmas Day in 1909. The five-masted schooner Davis Palmer struck Finn’s Ledge and sank with all hands in the storm, and some of the wreckage came ashore at Little Brewster Island.

Alfred M. Horte had a brief stay as keeper after the death of Bates. Henry L. Pingree was keeper from 1894 to 1909. Pingree’s son, Wesley, who was an assistant keeper at Deer Island Light in Boston Harbor, married Horte’s sister, Josephine.

An auxiliary light was added to the station in 1890—a fixed white light exhibited from a small wooden building. The light was designed to help mariners avoid dangerous Harding’s Ledge. If they strayed too far from the channel to either side, a red light was seen.

The next keeper, Levi B. Clark, weathered a tremendous blizzard on Christmas Day in 1909. The five-masted schooner Davis Palmer struck Finn’s Ledge and sank with all hands in the storm, and some of the wreckage came ashore at Little Brewster Island.

Charles Jennings, a Cape Cod native previously stationed at Monomoy Point Light, became keeper in 1916 at a yearly salary of $804. Jennings, who received a commendation from the secretary of Commerce for the rescue of 24 men from the navy patrol boat Alacrity, moved on to be the keeper of the range lights at Lovell’s Island in 1919.

J. Lelan Hart was keeper from 1919 to 1926. In 1921, Hart and his assistant, William J. Howard—who later gained fame as a lifesaver at Wing’s Neck Light—were credited with saving the life of the second assistant keeper, whose boat had capsized. Hart was involved in several more rescues during his stay.

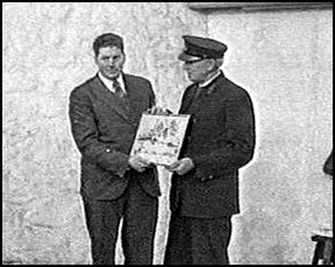

Left: The unveiling of a tablet at Boston Light on December 2, 1934, listing the station’s keepers. From left to right: J. Lelan Hart, keeper from 1919 to 1926; Charles Jennings, keeper from 1916 to 1919; Maurice Babcock, keeper from 1926 to 1941, and Fitz-Henry Smith, author of the 1911 book The Story of Boston Light. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

Archford "Ted" Haskins was first assistant keeper for almost a decade beginning in 1927. Every chore was more difficult at an island light station. When she wanted to wash the family's clothes, Haskins' wife, Betty, had to collect the water a bucket at a time from the basement. The water would be heated on a stove overnight, and the clothes were washed using a washboard and lye soap.

The Haskins children spent weekends and vacations on the island, and stayed in a boardinghouse on the mainland during the school week. Transportation was via a small boat called the Dolittle -- so named because it did little.

Circa early 1930s view

Ted Haskins picked up large quantities of food on the mainland when he had the opportunity. Canned food comprised most of the family's diet in winter. “If they had to have corn chowder three nights in a row, that’s what they did," said Haskins' daughter Marla Haskins Rogers in an interview many years later.

Maurice A. Babcock, formerly at Thacher Island, Bird Island, and Gay Head, was principal keeper from 1926 to 1941. In 1934, members of the Bostonian Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society held a ceremony on Little Brewster honoring the 25 keepers of Boston Light.

Fitz-Henry Smith, author of a history of the lighthouse, unveiled a tablet bearing the names of the keepers. The modest and taciturn Babcock was invited to speak.

Maurice A. Babcock, formerly at Thacher Island, Bird Island, and Gay Head, was principal keeper from 1926 to 1941. In 1934, members of the Bostonian Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society held a ceremony on Little Brewster honoring the 25 keepers of Boston Light.

Fitz-Henry Smith, author of a history of the lighthouse, unveiled a tablet bearing the names of the keepers. The modest and taciturn Babcock was invited to speak.

Here is the entire text of his speech:

Well, ladies and gentlemen, I am not much of an orator, but I enjoy keeping the light burning for the ships coming in, and the fog signal sounding. I thank you.

Left: Three keepers of Boston Light: Charles Jennings, Maurice Babcock, and J. Lelan Hart. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The Babcocks’ children boarded in the nearby towns of Winthrop or Hull so they could attend school, and they spent their vacations on Little Brewster. On one occasion, Keeper Babcock rowed through dangerous ice floes to Hull to pick up his son, Bill, during a February vacation. The keeper’s wife watched her husband fight off giant ice cakes as he headed for Hull. She lost sight of him for an agonizing two hours.

Finally, she caught sight of the returning dory, with her husband rowing and their son fending off the ice. “After I had given them a good scolding,” she later said, “I sat them down to a hot supper and we had a pleasant holiday.” Bill Babcock later carried on the family tradition, becoming a keeper at Graves Light in Boston Harbor.

The Babcocks’ children boarded in the nearby towns of Winthrop or Hull so they could attend school, and they spent their vacations on Little Brewster. On one occasion, Keeper Babcock rowed through dangerous ice floes to Hull to pick up his son, Bill, during a February vacation. The keeper’s wife watched her husband fight off giant ice cakes as he headed for Hull. She lost sight of him for an agonizing two hours.

Finally, she caught sight of the returning dory, with her husband rowing and their son fending off the ice. “After I had given them a good scolding,” she later said, “I sat them down to a hot supper and we had a pleasant holiday.” Bill Babcock later carried on the family tradition, becoming a keeper at Graves Light in Boston Harbor.

In the video clip above, recorded in 1988, Maurice Babcock, Jr. describes the efforts of his father and the other keepers during the great hurricane of September 21, 1938.

The Babcocks were on the island for the devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938, which struck New England without warning. As the winds picked up late that afternoon, Keeper Babcock had to crawl on his hands and knees to reach the lighthouse.

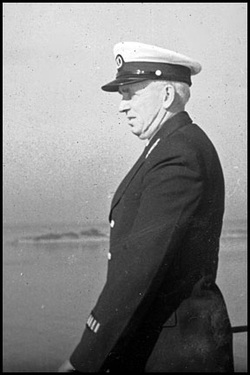

Maurice Babcock

A dock at the island was wrecked by the storm. Babcock and one of his assistants spent the night in the lighthouse lantern, making sure the light stayed lit. Babcock’s log entries, now at the National Archives, make note of the storm but mention nothing of his own extraordinary efforts.

In late 1939, Keeper Babcock lost part of a finger in an accident with a motor on the island. He spent a few weeks in Boston recuperating. In a newspaper article during that period, he said that he had never driven an automobile and had no intention of doing so. By boat, he could reach Boston’s South Station in 50 minutes, much faster than the trip by car from Hull. “We do our shopping for groceries just as anybody else does,” he told the reporter. “The only difference is that we are farther from the store. We lay in larger supplies than most people, on account of the distance. We can’t trot out to the chain store if we happen to forget the coffee.”

Friends of the Babcocks threw the family a farewell party on the island on the day of the keeper’s retirement in November 1941.

In late 1939, Keeper Babcock lost part of a finger in an accident with a motor on the island. He spent a few weeks in Boston recuperating. In a newspaper article during that period, he said that he had never driven an automobile and had no intention of doing so. By boat, he could reach Boston’s South Station in 50 minutes, much faster than the trip by car from Hull. “We do our shopping for groceries just as anybody else does,” he told the reporter. “The only difference is that we are farther from the store. We lay in larger supplies than most people, on account of the distance. We can’t trot out to the chain store if we happen to forget the coffee.”

Friends of the Babcocks threw the family a farewell party on the island on the day of the keeper’s retirement in November 1941.

Maurice Babcock, Jr., son of Keeper Maurice Babcock, interviewed at his home in Lubec, Maine, in 1988

The historian Edward Rowe Snow accompanied Babcock on his final trip up the lighthouse stairs.

Snow later wrote:

It was a sad journey we made that afternoon, and as we reached the lantern room he looked fondly at the lenses and the lighting apparatus with its gas mantle, all of which he would never see again.

Then Maurice Babcock, twenty-fifth keeper of Boston Light, stepped out on the platform that surrounds the tower and looked out to sea. Neither of us spoke, but each knew what was in the other’s mind—the old days of the lighthouse service were gone forever, never to return.

Left: Maurice Babcock in Oct. 1941, shortly before his retirement. Courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The Coast Guard took over the management of the nation’s lighthouses in 1939, and civilian keepers were given the option of remaining civilians or joining the Coast Guard. Ralph C. Norwood, an assistant under Maurice Babcock, enlisted in the Coast Guard and became the next keeper in 1941.

The 1930s had been exciting years for the Norwoods. In 1932, Josephine Norwood, Ralph’s wife, was expecting their seventh child. (She would have nine children by the time she reached 27.) During a spring storm, Josephine believed the birth was imminent and a doctor was summoned from Hull. It took an hour and a half for the boat to land at the island in heavy seas. As it turned out, Georgia wasn’t born until a week later in calm weather, but the headlines from the night of the storm forever stamped Georgia as the “Storm Child.”

It was a sad journey we made that afternoon, and as we reached the lantern room he looked fondly at the lenses and the lighting apparatus with its gas mantle, all of which he would never see again.

Then Maurice Babcock, twenty-fifth keeper of Boston Light, stepped out on the platform that surrounds the tower and looked out to sea. Neither of us spoke, but each knew what was in the other’s mind—the old days of the lighthouse service were gone forever, never to return.

Left: Maurice Babcock in Oct. 1941, shortly before his retirement. Courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

The Coast Guard took over the management of the nation’s lighthouses in 1939, and civilian keepers were given the option of remaining civilians or joining the Coast Guard. Ralph C. Norwood, an assistant under Maurice Babcock, enlisted in the Coast Guard and became the next keeper in 1941.

The 1930s had been exciting years for the Norwoods. In 1932, Josephine Norwood, Ralph’s wife, was expecting their seventh child. (She would have nine children by the time she reached 27.) During a spring storm, Josephine believed the birth was imminent and a doctor was summoned from Hull. It took an hour and a half for the boat to land at the island in heavy seas. As it turned out, Georgia wasn’t born until a week later in calm weather, but the headlines from the night of the storm forever stamped Georgia as the “Storm Child.”

In the above video clip, recorded in October 1991 at Boston Light, Josephine Norwood recalls the birth of her daughter Georgia in 1932.

The writer Ruth Carmen based a novel called Storm Child on the story. The book was a highly fictionalized version of the Norwoods’ story that even included a tidal wave destroying the lighthouse.

Georgia Norwood

Georgia and her parents were showered with publicity, and they traveled to New York City to appear on the nationally broadcast We the People radio program.

Hollywood subsequently came calling to make a movie version of Storm Child, and five-year-old Georgia was slated to play herself. Described as “smiling and sunny-curled,” Georgia was to be the “Bay State’s own Shirley Temple.” The movie never happened. “I would not separate the children,” said Josephine. “Each one was as precious as the other and they all needed my supervision.” Apparently Georgia agreed, reportedly saying, “I don’t want to go to Hollywood. I want to go back to Boston Light.”

The legend of the Storm Child lived on just the same. Georgia’s son, Willie Emerson, later wrote a book called First Light, which relating relates the true story of his mother’s birth and life at Boston Light.

“The days spent on Boston Light were busy ones,” Josephine told her grandson for his book, “with eleven of us to cook for. . . . As we never knew when inspection of the houses, tower and fog signal would be held, it was a matter of course to have the beds made, the dishes done, and the sweeping and dry mopping done by ten o’clock. Of course our children were brought up to help with the work. Then they had their time to swim, go fishing, walking over the bar at low tide, or go rowing.”

Hollywood subsequently came calling to make a movie version of Storm Child, and five-year-old Georgia was slated to play herself. Described as “smiling and sunny-curled,” Georgia was to be the “Bay State’s own Shirley Temple.” The movie never happened. “I would not separate the children,” said Josephine. “Each one was as precious as the other and they all needed my supervision.” Apparently Georgia agreed, reportedly saying, “I don’t want to go to Hollywood. I want to go back to Boston Light.”

The legend of the Storm Child lived on just the same. Georgia’s son, Willie Emerson, later wrote a book called First Light, which relating relates the true story of his mother’s birth and life at Boston Light.

“The days spent on Boston Light were busy ones,” Josephine told her grandson for his book, “with eleven of us to cook for. . . . As we never knew when inspection of the houses, tower and fog signal would be held, it was a matter of course to have the beds made, the dishes done, and the sweeping and dry mopping done by ten o’clock. Of course our children were brought up to help with the work. Then they had their time to swim, go fishing, walking over the bar at low tide, or go rowing.”

In the 1930s, there were three families and as many as 19 children living on the tiny island. The school-aged Norwood children lived with their mother in Hull during the school year, but they always looked forward to their glorious summers on the island.

“You never relaxed until they were all safely in bed at night,” said Josephine. She once rigged a leash attached to the clothesline for her young son, Bobbie, but “Georgia felt sorry for him and untied him.”

Ralph Norwood’s daughter, Priscilla (Reece), later remembered that her father would go to Hull once a month for groceries. “Sometimes he would take one of us kids with him,” she recalled,. “and the grocers would feel sorry and give you a cabbage or something.” Attempts to maintain a vegetable garden on the island met with little success, as the soil was poor.

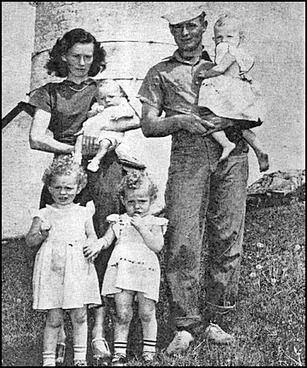

Left: The Norwood family in 1946. Back row: Georgia, Wanda, Fay, Josephine, Ralph Front row: Bob, Bruce, Dexter, Priscilla, Gail, Ralph II, Spunky Courtesy of Willie Emerson.

Ralph Norwood’s daughter, Priscilla (Reece), later remembered that her father would go to Hull once a month for groceries. “Sometimes he would take one of us kids with him,” she recalled,. “and the grocers would feel sorry and give you a cabbage or something.” Attempts to maintain a vegetable garden on the island met with little success, as the soil was poor.

Left: The Norwood family in 1946. Back row: Georgia, Wanda, Fay, Josephine, Ralph Front row: Bob, Bruce, Dexter, Priscilla, Gail, Ralph II, Spunky Courtesy of Willie Emerson.

The Norwoods, of course, always had plenty of seafood. The children would harvest the plentiful crabs, periwinkles, and mussels from the shores of the island. The older children made money by lobstering.

Courtesy of Willie Emerson

Summers were lively, with filled with rowboat races and pie- eating contests with the children who summered on nearby Great Brewster Island. Games of all sorts were played; even baseball was played on Great Brewster —in the water was an instant automatic out.

Life was generally harmonious, although Maurice Babcock Jr. did get a punch in the nose once from one of the Norwood girls. He had trespassed onto the Norwoods’ part of the island.

In the winters, the children boarded in Hull or Winthrop where they attended school, waiting eagerly for vacations and their glorious summers back on Little Brewster.

Life was generally harmonious, although Maurice Babcock Jr. did get a punch in the nose once from one of the Norwood girls. He had trespassed onto the Norwoods’ part of the island.

In the winters, the children boarded in Hull or Winthrop where they attended school, waiting eagerly for vacations and their glorious summers back on Little Brewster.

The Norwoods left the island in 1945. Bruce Norwood said years later, “I’ve never been in another place that felt like the home Boston Light was.”

The LaVigne family at Boston Light

One of Ralph and Josephine’s sons, Gail, later became a lightkeeper in Nova Scotia, making four generations of keepers in the family.

Boston Light was extinguished during World War II, and it went back into operation in July 1945. The light was converted to electricity in 1948, and shortly after that the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens was replaced by an electric motor. The second-order Fresnel lens remains in use today.

Joseph E. LaVigne was the Coast Guard keeper from 1948 to 1950. LaVigne had joined the Coast Guard as a teenager and was aboard the USS Menges when it was torpedoed near Algeria in May 1944.

LaVigne installed the first indoor bathroom on the island in 1949, at his wife's request. His wife, Mary Ellen LaVigne, had a child at Boston Light in March 1950 -- the second child born ever born at the light station. When the baby’s birth was imminent, low tide prevented the keeper from launching a boat to get his wife to the mainland.

A doctor eventually was rushed over from Pemberton Point in Hull in a Coast Guard boat, and Joseph Jr. was delivered at 7:30 a.m. Mary Ellen was later taken to Quincy City Hospital to recuperate. Joseph Jr., was the couple’s first son and their fourth child.

Boston Light was extinguished during World War II, and it went back into operation in July 1945. The light was converted to electricity in 1948, and shortly after that the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens was replaced by an electric motor. The second-order Fresnel lens remains in use today.

Joseph E. LaVigne was the Coast Guard keeper from 1948 to 1950. LaVigne had joined the Coast Guard as a teenager and was aboard the USS Menges when it was torpedoed near Algeria in May 1944.

LaVigne installed the first indoor bathroom on the island in 1949, at his wife's request. His wife, Mary Ellen LaVigne, had a child at Boston Light in March 1950 -- the second child born ever born at the light station. When the baby’s birth was imminent, low tide prevented the keeper from launching a boat to get his wife to the mainland.

A doctor eventually was rushed over from Pemberton Point in Hull in a Coast Guard boat, and Joseph Jr. was delivered at 7:30 a.m. Mary Ellen was later taken to Quincy City Hospital to recuperate. Joseph Jr., was the couple’s first son and their fourth child.

In November 1952, a 22-year-old Coast Guardsman and Newton, Massachusetts, native stationed at the lighthouse, Seaman Richard B. Fredey, traveled in one of the station's 14-foot boats to the Hull Yacht Club. The boat was powered by a five-horsepower outboard motor. With him was Wilford MacNeill, a 53-year-old civilian contractor who was doing work on the island. They were last seen in Hull around 3:30 a.m. on November 21.

When they failed to return by later in the morning, an intensive search was conducted. MacNeill's body was later found, and Fredey was presumed dead. Fredey left his wife and a six-month-old daughter, and MacNeill left a wife and two children.

Right: Richard Fredey and his daughter, Jill, at Boston Light. Courtesy of Jill Fredey Doering.

In 1960, it was decided that the smaller 1885 seven-room keeper’s house would suffice for the island’s Coast Guard personnel. The 1859 duplex dwelling had badly deteriorated’ deteriorated. a A 1949 inspection reported that the ceiling in the kitchen was falling down and there were rat holes in the house. The Coast Guard razed the house structure in the spring of 1960. After that, Coast Guardsmen lived at the station without their families.

When they failed to return by later in the morning, an intensive search was conducted. MacNeill's body was later found, and Fredey was presumed dead. Fredey left his wife and a six-month-old daughter, and MacNeill left a wife and two children.

Right: Richard Fredey and his daughter, Jill, at Boston Light. Courtesy of Jill Fredey Doering.

In 1960, it was decided that the smaller 1885 seven-room keeper’s house would suffice for the island’s Coast Guard personnel. The 1859 duplex dwelling had badly deteriorated’ deteriorated. a A 1949 inspection reported that the ceiling in the kitchen was falling down and there were rat holes in the house. The Coast Guard razed the house structure in the spring of 1960. After that, Coast Guardsmen lived at the station without their families.

Boatswain’s Mate First Class William “Mike” Mikelonis was the Coast Guard keeper at Boston Light for several years beginning in 1962. The Coast Guard staff at that time spent two weeks on the island and one week off.

The remaining 1885 keeper's house

Mikelonis and other keepers over the years have enjoyed great fishing off the ledges. When Mikelonis retired in 1967, he said he had caught more than 1,000 striped bass, two of them over 50 pounds. Upon his retirement, Mikelonis was presented with the bulb that burned in the tower on his last day of duty.

Mikelonis shared the island with two assistants and a shaggy black dog named Salty, one of a long line of Boston Light dogs. Salty was succeeded by Salty II, and later by Farah (named during the era of Charlie’s Angels and Farah Fawcett), a friendly mutt who lived for 13 years on Little Brewster. Farah would whine and shake when taken to the mainland. Once, at low tide, Farah wandered over to Great Brewster Island, and 11 puppies resulted from her short trip away from home. Farah died in November 1989, and her final resting place is a marked grave not far from the cistern building.

The story below about Bear, another dog at Boston Light in the 1960s, was written by David Vitale, one of the Coast Guard keepers circa 1967-69.

Mikelonis shared the island with two assistants and a shaggy black dog named Salty, one of a long line of Boston Light dogs. Salty was succeeded by Salty II, and later by Farah (named during the era of Charlie’s Angels and Farah Fawcett), a friendly mutt who lived for 13 years on Little Brewster. Farah would whine and shake when taken to the mainland. Once, at low tide, Farah wandered over to Great Brewster Island, and 11 puppies resulted from her short trip away from home. Farah died in November 1989, and her final resting place is a marked grave not far from the cistern building.

The story below about Bear, another dog at Boston Light in the 1960s, was written by David Vitale, one of the Coast Guard keepers circa 1967-69.

|

|

Left: Video of Farah, circa late 1980s.

A later dog was named Shadwell in honor of the slave who drowned with the first keeper. Cats have also lived at the station, including a frisky black cat named Ida Lewis, after America’s most famous woman lighthouse keeper. |

|

Some people have reported weird happenings on Little Brewster over the years. Russell Anderson was a Coast Guard keeper in 1947. One day, his 22-year-old wife, Mazie, was walking along the shore. She heard footsteps close behind her, but saw no one when she turned around. That night as she tried to sleep, Mazie felt a presence in the room. Later she heard what she described as “horrible maniacal laughter” coming from the boathouse. On another night she heard the same sound coming from the fog signal house. This time a little girl’s sobbing voice followed, calling “Shaaaadwell!” over and over.

Right: Video of Keeper Dennis Dever, circa 1989. Mazie Anderson related this story in an article for Yankee magazine many years later. She said that on one occasion the fog signal engines started themselves and the light mysteriously went on by itself. Mazie saw a mysterious unfamiliar figure outlined against the lens. |

|

Soon she again heard the man’s laughing voice and the girl’s sobbing cries. It wasn’t until years later that Mazie Anderson read that the Boston Light slave’s name was Shadwell—the same name repeated by the little girl’s voice.

Left: This small museum of artifacts in the base of the tower was started by CWO Ken Black, officer in charge at Coast Guard Station Point Allerton in the 1960s.

Petty Officer First Class Dennis Dever, the Coast Guard officer in charge in the late 1980s, had a few odd experiences. While working in the station’s boathouse, he liked to have his radio tuned to a rock station. Often, with nobody else in the boathouse, the station would change itself to a classical station. Dever said he and other Coast Guard crew attributed events like this to “Old George”—Worthylake, that is.

One day, Dever was in the kitchen of the keeper’s house looking out the window at the tower, and he clearly saw a man in the lantern room. This was alarming, as the only other person on the island was his assistant in the next room. From a distance, it appeared that the figure at the top of the tower was wearing an old fashioned keeper’s uniform. Dever rushed to the tower and went up the stairs, finding but he found the lantern room empty.

Reports of mysterious figures seen in the tower and in the keeper’s house continue to the present day. A number of people have described the ghostly figure of a woman in a white nightgown at the top of the tower.

Petty Officer First Class Dennis Dever, the Coast Guard officer in charge in the late 1980s, had a few odd experiences. While working in the station’s boathouse, he liked to have his radio tuned to a rock station. Often, with nobody else in the boathouse, the station would change itself to a classical station. Dever said he and other Coast Guard crew attributed events like this to “Old George”—Worthylake, that is.

One day, Dever was in the kitchen of the keeper’s house looking out the window at the tower, and he clearly saw a man in the lantern room. This was alarming, as the only other person on the island was his assistant in the next room. From a distance, it appeared that the figure at the top of the tower was wearing an old fashioned keeper’s uniform. Dever rushed to the tower and went up the stairs, finding but he found the lantern room empty.

Reports of mysterious figures seen in the tower and in the keeper’s house continue to the present day. A number of people have described the ghostly figure of a woman in a white nightgown at the top of the tower.

The video above is from a press conference at Boston Light on October 23, 1989, when Senator Edward M. Kennedy announced funding to keep Boston Light a staffed light station.

By 1989, the Coast Guard had automated almost every lighthouse in the United States and Boston Light was scheduled to be the last in this process. Preservation groups appealed to Congress and the Coast Guard, and with the help of Senator Edward M. Kennedy funding was appropriated to keep Coast Guard staff on Little Brewster, making the island a living museum of lighthouse history.

In 1990, Historic Boston, Inc., and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management commissioned a Stewardship Plan and preservation guidelines for Boston Light. As a result of the study, much work has been done on the island in recent years, including the replacing of trim on the keeper's house and the repainting of all the buildings.

Left: Sally Snowman (right) in 2003 with Connie Small, author of the book The Lighthouse Keeper's Wife.

Boston Light became the last lighthouse in the United States to be automated on April 16, 1998, but a Coast Guard crew continued to perform all the other traditional keepers' duties except for turning the light on at sunset and turning it off at sunrise. The light currently operates 24 hours a day.

Coast Guard Auxiliary (volunteer) personnel have worked on the island since 1980, and women have often been part of the crew. Auxiliarists Sally Snowman and James Thomson of Plymouth, Massachusetts, were married on Little Brewster Island in 1994. The couple published a book called Boston Light: A Historical Perspective.It was the first book written about Boston Light's history in over 80 years.

Left: Sally Snowman (right) in 2003 with Connie Small, author of the book The Lighthouse Keeper's Wife.

Boston Light became the last lighthouse in the United States to be automated on April 16, 1998, but a Coast Guard crew continued to perform all the other traditional keepers' duties except for turning the light on at sunset and turning it off at sunrise. The light currently operates 24 hours a day.

Coast Guard Auxiliary (volunteer) personnel have worked on the island since 1980, and women have often been part of the crew. Auxiliarists Sally Snowman and James Thomson of Plymouth, Massachusetts, were married on Little Brewster Island in 1994. The couple published a book called Boston Light: A Historical Perspective.It was the first book written about Boston Light's history in over 80 years.

In September 2003, Sally Snowman was appointed as the new civilian keeper -- the first civilian keeper since the Coast Guard took over in 1941, and the first woman keeper in the lighthouse's long history.

During a 1996 renovation

The active duty Coast Guard personnel that had been assigned to the island were relocated to meet the needs of Homeland Security. There is one Coast Guard engineer currently assigned to work with the keeper to ensure the facility is sufficiently maintained. The Coast Guard Auxiliary personnel at Boston Light are now referred to as Watchstanders, and in 2000 a program was established for their training.

National Park rangers are also present during the days the island is open from June to October. The rangers are there during the day only, while the Watchstander Program requires staying overnight on the island for four to seven-day stretches.

You can see Boston Light distantly from the shores of Hull, Revere and Winthrop, and from high buildings in Boston. The Friends of the Boston Harbor Islands run several special trips to Little Brewster Island every summer, and the National Park Service runs trips from Boston in season. Visitors on these trips get to climb the 76 stairs to the top of Boston Light for a breathtaking view of Boston Harbor.

If you visit Little Brewster be sure to look on the rocks for initials and names carved by keepers and visitors to Boston Light, some dating back to the 1700s.

National Park rangers are also present during the days the island is open from June to October. The rangers are there during the day only, while the Watchstander Program requires staying overnight on the island for four to seven-day stretches.

You can see Boston Light distantly from the shores of Hull, Revere and Winthrop, and from high buildings in Boston. The Friends of the Boston Harbor Islands run several special trips to Little Brewster Island every summer, and the National Park Service runs trips from Boston in season. Visitors on these trips get to climb the 76 stairs to the top of Boston Light for a breathtaking view of Boston Harbor.

If you visit Little Brewster be sure to look on the rocks for initials and names carved by keepers and visitors to Boston Light, some dating back to the 1700s.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

PRINCIPAL KEEPERS and COAST GUARD OFFICERS IN CHARGE

George Worthylake (1716-1718); Robert Saunders (1718); John Hayes (1718-1733); Robert Ball (1733-1774); William Minns (1774-1776); Thomas Knox (1783-1811); Jonathan Bruce (1811-1833); David Tower (1833-1844); Joshua Snow (1844); Tobias Cook (1844-1849); William Long (1849-1851); Zebedee Small (1851-1853); Hugh Douglass (1853-1856); Moses Barrett (1856-1862); Charles E. Blair (1862-1864); Thomas Bates, Jr. (1864-1893); Alfred Williams (1893); Albert M. Horte (1893-1894); Henry L. Pingree (1894-1909); F. E. Tarr (1909-1910); Levi B. Clark (1910-1911); George Kezer (1911); Mills Gunderson (1911-1916); Charles H. Jennings (1916-1919); James Lelan Hart (1919-1926); Maurice Babcock (1926-1941); Ralph C. Norwood, (Lighthouse Service then Coast Guard, 1941-1945); Franklin A. Goodwin (Coast Guard, 1945); Julio DiFuria (Coast Guard, 1945-1946); Eldon W. Beal (Coast Guard, 1946); Leo F. Gracie (Coast Guard, 1946-1948); Stanley Batt (Coast Guard, 1948); Joseph F. LaVigne (Coast Guard, 1948-1950); John D. Hall (Coast Guard, 1950); Robert C. Merchant (Coast Guard, 1950-1951); Clinton M. Davis (Coast Guard, 1951); Ray O. Beard (Coast Guard, 1951-1952); Robert A. Reedy (Coast Guard, 1952); John Curran (Coast Guard, 1952-1953); Paul B. Guy (Coast Guard, 1953-1954); Hubert B. Jones (Coast Guard, 1954-1955); John E. Horner (Coast Guard, 1955-1959); J. B. Collins (Coast Guard, 1959-1960); Gottfried Schiffers (Coast Guard, 1960-1962); Wiiliam F. ("Mike") Mikelonis (Coast Guard, 1962-1967); Vernon T. Springer (Coast Guard, 1967-1969); Allick Rust (Coast Guard, 1969-1971); Dennis I. Reed (Coast Guard, 1971-1972); Edward J. O'Shea (Coast Guard, 1972-1973); James H. Clark, Jr. (Coast Guard, 1973-1974); James H. Turner (Coast Guard, 1974-1975); Alan D. Achorn (Coast Guard, 1975-1977); Carlon F. Brietzke (Coast Guard, 1977-1978); Marvin D. Gonzalaus (Coast Guard, 1978-1980); Harold L. Murra (Coast Guard, 1980-1982); James F. Burt (Coast Guard, 1982-1984); Paul V. Dodds (Coast Guard, 1984-1985); Guy A. Veillette (Coast Guard, 1985-1987); Joe B. Lanard (Coast Guard, 1987); K. J. Galvin (Coast Guard, 1987-1988); Dennis Dever (Coast Guard, 1988-1990); Alexander ("Sandy") Booth (Coast Guard, 1990-1992); Wesley J. Pannett (Coast Guard, 1992-1995); Reid Hair (Coast Guard, 1995-1997); Scott Stanton (Coast Guard, 1997-1999); Richard Himelrick (Coast Guard, 1999-2001), Petty Officer Pedro Gonzales (Coast Guard, 2001-2003), Sally Snowman (2003-)

ASSISTANTS and OTHER COAST GUARD PERSONNEL

Sylvester F. Douglas (1854-?); Joseph Hammond (1856); Charles Hooper (1856-1857); Joseph Wonson (first asst., 1859-1862); J W. Wonson (second asst., 1859-1862); Walter Hooper (second asst., 1861-1862); Marcellus A. Blair (second asst., 1862); Charles E. Blair (first asst., 1862); Charles H. Barrett (second asst., 1862-1863); Wallace D. Hooper (first asst., 1862-1865); Peter Harrington (second asst., 1863-?); John C. Connell (1863-1866); Robert Shore (1863-1866); William Hooper (1865); Lyman Ford (1865); Joshua L. Bates (1865-1870); N. H. Woodbury (1866-1867); Alexander Tolman (1867-?); John Sheehan (1868); George A. Ordway (1868); William H. Sylvester (1868-1869); Walter Colby (second asst., 1869-1870); Daniel McKenzie (1870-1872); Fred Hammond (first asst., 1872-1877); David Keating (second asst., 1875-1876); George G. Baily (second asst., 1876-1877, first asst., 1877-1882); John Philbrook (second asst., 1877-?); E. Lewis Gorham (second asst., 1877-1878); William H. Hammond (second asst., 1878-1880); Edward L. Gorham (second asst., 1880-1882, first asst., 1882-1884); Alfred Gorham (second asst., 1882); Frank L. Carson (second asst., 1882-1884, first asst., 1884); Charles E. Turner (second asst., 1884-1886, first asst., 1886-1888); Henry L. Pingree (second asst., 1886-1888, first asst., 1888-1892); William Garvin (second asst., 1888); James P. Smith (second asst., 1888-1891); George G. Baily (second asst., 1891-1892); Albert M. Horte (second asst., 1892); Alfred Williams (first asst., 1892-1893); William A. D. Hadley (second asst., 1893); Gershom C. Freeman (second asst., 1893-1895, first asst., 1895); Wesley A. Pingree (first asst., 1894-1895); Daniel D. L. Donovan (second asst., 1895, first asst., 1895); Charles F. Stranger [Stanger ?] (second asst., 1895-1896, first asst., 1896); William A. Pool (second asst., 1895-1896, first asst., 1896-1899); Joseph Keller (second asst., 1896-1899, first asst., 1899-1902); Ernest R. Sylvester (second asst., 1900-?); George E. Kezer (first asst., 1901-1905); Daniel E. Harding (first asst., c. 1901); Levi B. Clark (second asst., 1902-1904, first asst., 1904-1905); Charles W. Jordan (second asst., 1904-1905); Henry C. Towle (second asst., 1905-1907); William H. Oliver (second asst., 1907-1908, first asst., 1908); Joseph Philip Sousa (second asst., 1908, first asst., 1908-1910); Andrew S. Nickerson (second asst., 1908, first asst., 1911-1913); Charles H. Jennings (first asst., 1909-1911); ? Huse (second asst., 1913); ? McLaughlin (second asst., 1915); Martin Rolland (second asst., 1915); William G. Burtt (second asst., 1911-1912); William G. Mailbette (second asst., 1912); ? Kerr (second asst., 1913); Carl Delano Hill (assistant, c. 1915-1916); James Lelan Hart (1916-1919); Charles Lyman (1916-1919); John A. Strout (c. 1920s); Ralph C. Norwood (1929-1941); William J. Howard (first asst., 1921-1923); Arthur Small (c.1917-1926); William Lane (first asst., 1927); Chester Wheeler (c. 1927); Archford Veron "Ted" Haskins (first asst., 1928-1937); J. E. Poyner (second asst., c. 1927); Frank J. Ponte (second asst., c. 1927); Osborne Earle Hallett (2nd assistant, 1937-1943); Leo W. Wertman, Jr. (Coast Guard, second asst., 1950); James L. Cook (Coast Guard, second asst., 1951); Edward R. Benway (Coast Guard, second asst., 1951-1952); Leon G. Lewis (Coast Guard, first asst., 1952); Edward Whitmore (Coast Guard, first asst., c. 1952); Richard B. Fredey (Coast Guard, second asst., 1952); John G. Steen (Coast Guard, first asst., 1958); William G. Desautels (Coast Guard, second asst., 1958); Norman J. Kauffer (Coast Guard, second asst., 1958); Judson E. Boardman (Coast Guard, first asst., 1960); Donald M. Nashawath (Coast Guard, 1962-1967); David L. Vitale (Coast Guard, 1967-1969); Alan Letto (Coast Guard, 1967-1969); Bert Glazier (Coast Guard, 1969-1971); Norman Gannon (Coast Guard, 1969-1971); Pete Perron (Coast Guard, c. 1980-1982); Roger Emmons (Coast Guard, c. 1980-1982); Robert N. Greeley (Coast Guard, 1983-1984); Tony Kuliak (Coast Guard, c. early 1980s); Michael Bennett (Coast Guard, 1983); Patrick Doherty (Coast Guard, c. 1984); C. F. Ingham (Coast Guard, c. 1985); Joseph Allairi (Coast Guard, c. 1980s); ? Finnogan (Coast Guard, c. 1980s); Steve Stark (Coast Guard, 1986-1987); ? Danbby [Danby ?] (Coast Guard, 1986); Don White (Coast Guard, 1987); Tom Corcoran (Coast Guard, c. 1980s); David D. Sandrelli (Coast Guard, (1988-?); Kevin King (Coast Guard, c. 1988); ? Berg (Coast Guard, 1988); L. E. Wilkinson (Coast Guard, 1988); Jeffrey Currier (Coast Guard, 1988); Alan W. Ux (Coast Guard, 1989); James E. McClurkin (Coast Guard, 1989); Charles Joseph Pulaski (Coast Guard, 1990); ? Rosenburg (Coast Guard, c. 1992-1995); ? Wheeler (Coast Guard, c. 1992-1995); Mark Clements (Coast Guard, 1991-1995); Sean McGerry (Coast Guard, 1995-1997); Matt Fendley (Coast Guard, 1996-1997); Kevin Staples (Coast Guard, 1997-1998); Jeremy Rohanna (Coast Guard, 1997-1999); Chris Southerland (Coast Guard, 1998-1999); Gary Fleming (Coast Guard, 1999); Kevin Cullen (Coast Guard, 1999), William Cavanaugh (Coast Guard, c. 2000)

PRINCIPAL KEEPERS and COAST GUARD OFFICERS IN CHARGE