History of Palmers Island Light, New Bedford, Massachusetts

Click here for a gallery of Palmers Island Light photos on SmugMug (prints and gift items available)

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Six-acre Palmers Island, in the Acushnet River on the west side of the entrance to New Bedford Harbor, has been the scene of great heroism and tragedy, and its lighthouse was once considered one of New England's most picturesque.

Palmers Island Light with its first "birdcage" style lantern room (U.S. Coast Guard)

For years the lighthouse and the island itself were sad victims of neglect and vandalism, but thanks to concerned citizens and officials of the city of New Bedford, the lighthouse is shining once again.

The island got its name from one of the first settlers of Dartmouth, William Palmer. Like Boston Harbor's Deer Island, Palmer's Island was used as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War in 1675-76. Most of these Indians were later sold into slavery in the West Indies.

The island was once much larger and heavily wooded. “The craggy rocks and old cedar trees formed a fine opportunity for the exercise of youthful romance,” wrote Daniel Ricketson in his 1858 volume, The History of New Bedford. Today, there’s not a tree to be found.

New Bedford was the whaling capital of the nation in the mid-nineteenth century. The whaling industry reached its peak in the 1850s, when New Bedford had a fleet of 239 ships. In his 1843 survey of the lighthouses along the coast, inspector I.W.P. Lewis pointed out the need for a lighthouse on Palmer's Island:

This island lies directly within the entrance to New Bedford Harbor. A single lamp beacon place upon it would add materially to the facilities requires on entering this important harbor.

The island got its name from one of the first settlers of Dartmouth, William Palmer. Like Boston Harbor's Deer Island, Palmer's Island was used as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War in 1675-76. Most of these Indians were later sold into slavery in the West Indies.

The island was once much larger and heavily wooded. “The craggy rocks and old cedar trees formed a fine opportunity for the exercise of youthful romance,” wrote Daniel Ricketson in his 1858 volume, The History of New Bedford. Today, there’s not a tree to be found.

New Bedford was the whaling capital of the nation in the mid-nineteenth century. The whaling industry reached its peak in the 1850s, when New Bedford had a fleet of 239 ships. In his 1843 survey of the lighthouses along the coast, inspector I.W.P. Lewis pointed out the need for a lighthouse on Palmer's Island:

This island lies directly within the entrance to New Bedford Harbor. A single lamp beacon place upon it would add materially to the facilities requires on entering this important harbor.

A lighthouse was built on the northern point of the island for $1,951 by Charles M. Pierce, a mason. It was first lighted on August 30, 1849, by William Sherman (sometimes spelled Shearman), the keeper. The 24-foot tower was built of rubblestone, with wooden windows and floors.

A walkway connected the lighthouse to the higher part of the island. Like many of the nation’s lighthouses at that time, the lamps were fueled by New Bedford whale oil.

An 1850 inspection reported:

Tower of the light-house built of stone, and tight; dwelling is of wood and somewhat leaky; lantern is a good one, and the whole taken together is a fair piece of work... Found the apparatus clean; but the dome of the lantern, whih was painted white, was just as black as could be -- casued by burning Mr. Rodman's lamp with whale oil. Swelling is too small and needs a porch.

Keeper Sherman left to become the toll collector on the Fairhaven Bridge in 1853. Charles D. Tuell, who remained keeper until 1861, replaced him. Joseph B. C. Tuell was born at the lighthouse to the keeper and his wife in 1858. When Joseph Tuell died in 1935, his ashes were spread over the island from an airplane.

An 1850 inspection reported:

Tower of the light-house built of stone, and tight; dwelling is of wood and somewhat leaky; lantern is a good one, and the whole taken together is a fair piece of work... Found the apparatus clean; but the dome of the lantern, whih was painted white, was just as black as could be -- casued by burning Mr. Rodman's lamp with whale oil. Swelling is too small and needs a porch.

Keeper Sherman left to become the toll collector on the Fairhaven Bridge in 1853. Charles D. Tuell, who remained keeper until 1861, replaced him. Joseph B. C. Tuell was born at the lighthouse to the keeper and his wife in 1858. When Joseph Tuell died in 1935, his ashes were spread over the island from an airplane.

Palmers Island saw much activity during the nineteenth century. In the 1860s, a hotel and dance hall were built on the southern side of the island, and visitors came by steamer from New Bedford.

The range light on the Fairhaven Bridge

The hotel became a favorite stop for returning whalers, and illegal activity grew rampant. The hotel closed around 1890 and an amusement park was built on the island. This park failed after a few years, and the old hotel building burned down in 1905.

George Cowie served as keeper from 1872 to 1891. He complained that the well water was brackish and that the smoke from New Bedford factories blew across the island, contaminating the cistern with soot. It's unclear if anything was done to remedy the situation.

From 1888 to 1891 a red light on the nearby Fairhaven Bridge (right) served as a range light with Palmer's Island Light. This arrangement helped mariners past Butlers Flats before the lighthouse was established there. Later for a time a light on the Wamsutta Mill served as a range light with Palmer's Island Light.

George Cowie served as keeper from 1872 to 1891. He complained that the well water was brackish and that the smoke from New Bedford factories blew across the island, contaminating the cistern with soot. It's unclear if anything was done to remedy the situation.

From 1888 to 1891 a red light on the nearby Fairhaven Bridge (right) served as a range light with Palmer's Island Light. This arrangement helped mariners past Butlers Flats before the lighthouse was established there. Later for a time a light on the Wamsutta Mill served as a range light with Palmer's Island Light.

The early 1900s saw a number of changes at Palmer's Island. A new fog bell and striking machinery were installed in 1900 in a pyramidal wooden tower.

Later, the fog bell was removed from this tower and placed in a structure that was attached to the lighthouse.

Left: The U.S.S. Constitution passes Palmer's Island, August 6, 1931

New stairs were also installed in the lighthouse in 1900. The following year 75 tons of rip-rap stones were placed on the beach to afford some protection in storms. An oil house was added in 1905.

Left: The U.S.S. Constitution passes Palmer's Island, August 6, 1931

New stairs were also installed in the lighthouse in 1900. The following year 75 tons of rip-rap stones were placed on the beach to afford some protection in storms. An oil house was added in 1905.

New Bedford Public Library

New Bedford Public Library

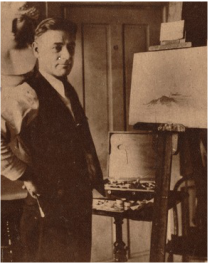

Arthur Small (left), a native of Brockton, Massachusetts, came to Palmers Island as keeper in 1922, moving with his wife, Mabel, and two sons from Boston Harbor's Narrows ("Bug") Light.

Small, one of three lighthouse keeper brothers, was a gifted artist who often painted scenes on Palmer's Island. He had been a seaman and lighthouse keeper since the age of 14. For 16 years Small served on the island, operating the light and fog bell.

The historian Edward Rowe Snow quoted Arthur Small’s comments on the importance of his work to the commerce of New Bedford Harbor:

It is a popular idea that there is very little to do except for striking a match once a day to light the lamp. Few of these landlubbers realize that if a fog comes in during the middle of the night the keeper must be ready to turn on the fog signal at once, for if the fog bell is silent for a moment, even then a great vessel may be feeling her way up into the harbor, depending on the ringing of the fog signal bell for her safety.

Small, one of three lighthouse keeper brothers, was a gifted artist who often painted scenes on Palmer's Island. He had been a seaman and lighthouse keeper since the age of 14. For 16 years Small served on the island, operating the light and fog bell.

The historian Edward Rowe Snow quoted Arthur Small’s comments on the importance of his work to the commerce of New Bedford Harbor:

It is a popular idea that there is very little to do except for striking a match once a day to light the lamp. Few of these landlubbers realize that if a fog comes in during the middle of the night the keeper must be ready to turn on the fog signal at once, for if the fog bell is silent for a moment, even then a great vessel may be feeling her way up into the harbor, depending on the ringing of the fog signal bell for her safety.

The channel in New Bedford Harbor is so narrow, that if a large vessel went down, all shipping in or out of the harbor would be at a standstill. The coal for the electric light company would not reach the pier, and the cotton steamers likewise would find it impossible to dock. In a short time all the city would be seriously crippled. That is what makes me angry when I hear of the easy job of a lighthouse keeper, as described by some fair weather sailor or inland resident.

Arthur and Mabel Small

In another interview, Keeper Small downplayed the so-called heroism of keepers:

Whenever they say anything about a lighthouse keeper, they always act as if he were some kind of hero. We’re not heroes. Here I am on this island, perfectly safe, working and painting pictures, while you wander around in New Bedford, crossing streets with automobiles and trolley cars whizzing by, just missing you by a few feet. Why, you people take more chances in a week than I do in ten years.

In 1988, a woman named Stella Hay Rex recalled attending a sewing circle with her friend Mabel Small on September 20, 1938. Mrs. Rex noticed that Mrs. Small was looking nervously out the window at the ocean. She asked Mrs. Small why she looked worried, and Mabel replied, "The sea is so rough I'm afraid Arthur won't be able to row over to get me if I wait for my ride."

Soon Mrs. Rex drove Mrs. Small to the landing where her husband was waiting to take her back to their lighthouse home. "See you girls next week!" shouted Mrs. Small as they left the dock.

On the afternoon of the following day, September 21, 1938, two days before Mabel Small's 48th birthday, the worst hurricane in New England history battered the south-facing coast. In the afternoon, as waves began to sweep over the island, Mabel Small took shelter in the oil house, on the highest part of the island. Keeper Small helped his wife secure a canvas bag containing their life savings -- around $8000 -- under her blouse.

Arthur Small was in the base of the lighthouse tower when a gigantic wave swept him out the door into the harbor. The following account is in Arthur Small's own words, cobbled from various interviews.

I was in the water, halfway between the island and Fort Phoenix. I'm a strong swimmer, and I began to work my way back toward Palmer's Island, using an overhand reach. But before I could get there I found myself surrounded by so much flotsam, broken boats, and house material that I could not reach land except by diving beneath the wreckage. I dove down, but I was badly injured by the floating debris before I reached shore.

I never saw my wife again, but I think she saw me washed overboard, and she ran to the boathouse and tried to unlash our boat which I had securely fastened. She was an expert boatswoman, but in her attempt to save my life she lost her own.

I was hurt and she knew it. Seeing the wave hit the boathouse was about the last thing I remember. I must have been hit by a big piece of timber and knocked unconscious.

I finally made the island and crawled up the stairs to the light, for I was so badly hurt I could not walk. My only thought was that the light must be kept burning. I was able to turn it on and to start the foghorn. I hoped I would attract attention, for there was no fog that night. Men in the Pierce and Kilburn Boat Yards at Fairhaven heard the fog horn and rowed over to see what was the matter. They found me lying in the tower, and even though the oilhouse was the only building remaining on the island, except the lighthouse, they found no trace of Mabel. They rowed me back to their boat yard, and I was taken from there to St. Luke's Hospital in an ambulance.

Whenever they say anything about a lighthouse keeper, they always act as if he were some kind of hero. We’re not heroes. Here I am on this island, perfectly safe, working and painting pictures, while you wander around in New Bedford, crossing streets with automobiles and trolley cars whizzing by, just missing you by a few feet. Why, you people take more chances in a week than I do in ten years.

In 1988, a woman named Stella Hay Rex recalled attending a sewing circle with her friend Mabel Small on September 20, 1938. Mrs. Rex noticed that Mrs. Small was looking nervously out the window at the ocean. She asked Mrs. Small why she looked worried, and Mabel replied, "The sea is so rough I'm afraid Arthur won't be able to row over to get me if I wait for my ride."

Soon Mrs. Rex drove Mrs. Small to the landing where her husband was waiting to take her back to their lighthouse home. "See you girls next week!" shouted Mrs. Small as they left the dock.

On the afternoon of the following day, September 21, 1938, two days before Mabel Small's 48th birthday, the worst hurricane in New England history battered the south-facing coast. In the afternoon, as waves began to sweep over the island, Mabel Small took shelter in the oil house, on the highest part of the island. Keeper Small helped his wife secure a canvas bag containing their life savings -- around $8000 -- under her blouse.

Arthur Small was in the base of the lighthouse tower when a gigantic wave swept him out the door into the harbor. The following account is in Arthur Small's own words, cobbled from various interviews.

I was in the water, halfway between the island and Fort Phoenix. I'm a strong swimmer, and I began to work my way back toward Palmer's Island, using an overhand reach. But before I could get there I found myself surrounded by so much flotsam, broken boats, and house material that I could not reach land except by diving beneath the wreckage. I dove down, but I was badly injured by the floating debris before I reached shore.

I never saw my wife again, but I think she saw me washed overboard, and she ran to the boathouse and tried to unlash our boat which I had securely fastened. She was an expert boatswoman, but in her attempt to save my life she lost her own.

I was hurt and she knew it. Seeing the wave hit the boathouse was about the last thing I remember. I must have been hit by a big piece of timber and knocked unconscious.

I finally made the island and crawled up the stairs to the light, for I was so badly hurt I could not walk. My only thought was that the light must be kept burning. I was able to turn it on and to start the foghorn. I hoped I would attract attention, for there was no fog that night. Men in the Pierce and Kilburn Boat Yards at Fairhaven heard the fog horn and rowed over to see what was the matter. They found me lying in the tower, and even though the oilhouse was the only building remaining on the island, except the lighthouse, they found no trace of Mabel. They rowed me back to their boat yard, and I was taken from there to St. Luke's Hospital in an ambulance.

Mabel Small had not survived. Her body was later found and identified in Fairhaven. Many of Keeper Small’s paintings were lost in the hurricane, along with his large library of several hundred books.

Arthur Small (courtesy of Jeremy Burnham)

Someone later asked Arthur Small what happened to the money Mabel had secured under her blouse. "Someone must have cut the cord about her neck and taken the bag," he said. "It could not have come loose in any other way. I have no clue to it. But that doesn't matter now. If only I could have Mabel back with me."

Many of Arthur Small's paintings were lost in the hurricane, along with his large library of several hundred books. He eventually recuperated at the Chelsea Naval Hospital near Boston, and he returned to duty as a lighthouse keeper at Hospital Point Light in Beverly, Massachusetts, where he finished his career a few years later.

The Boston Traveler reported:

Mrs. Small, wife and mother, perished in a moment of high bravery attempting to go the aid of her man. Arthur Small went through a living death during those black hours of Wednesday night while held captive in the lighthouse tower. High bravery was his in not challenging hopeless odds that the storm had set up.

Three days after the storm, Commissioner Harold D. King of the Bureau of Lighthouses called Arthur Small's performance during the storm "one of the most outstanding cases of loyalty and devotion that has come to the attention of this office."

Many of Arthur Small's paintings were lost in the hurricane, along with his large library of several hundred books. He eventually recuperated at the Chelsea Naval Hospital near Boston, and he returned to duty as a lighthouse keeper at Hospital Point Light in Beverly, Massachusetts, where he finished his career a few years later.

The Boston Traveler reported:

Mrs. Small, wife and mother, perished in a moment of high bravery attempting to go the aid of her man. Arthur Small went through a living death during those black hours of Wednesday night while held captive in the lighthouse tower. High bravery was his in not challenging hopeless odds that the storm had set up.

Three days after the storm, Commissioner Harold D. King of the Bureau of Lighthouses called Arthur Small's performance during the storm "one of the most outstanding cases of loyalty and devotion that has come to the attention of this office."

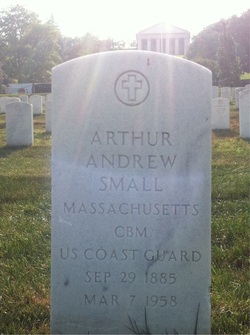

When Arthur Small died in 1958, the Coast Guard honored him with a burial at Arlington National Cemetery (below). A plaque honoring Arthur and Mabel Small can be seen today on the Fairhaven side of the harbor at Fort Phoenix.

Click here to read more about the story of Arthur and Mabel Small.

After the hurricane Franklin Ponte, formerly an assistant at Boston Light, went to Palmer's Island Light as a temporary keeper. Ponte's nephew, Joseph Ponte, served as an assistant. All that was left was the lighthouse tower and the oil house, and Joseph Ponte said that he and his uncle lived for a almost a month in the lighthouse before the Coast Guard sent a garage that was converted into living quarters. The light was automated in 1941; Martin Maloney was the last keeper .

With the construction of a massive hurricane wall in New Bedford Harbor in 1963 the lighthouse was deemed useless. Palmers Island, adjacent to the new wall, became more easily accessible to lighthouse seekers and vandals alike. The island passed through various owners, including radio station WBSM. The tower was burned by arsonists in 1966, gutting the interior and practically destroying the lantern room.

In 1978 ownership of Palmers Island went from Norlantic Diesel to the City of New Bedford, and local resident Dr. John O'Toole mounted a preservation effort. New Bedford youngsters picked up 20 tons of trash and debris from the island, which they converted into $300 for the lighthouse fund. A new fiberglass lantern was constructed to replace the badly burned one, and a 500-pound steel door was installed. The New Bedford Fire Department contributed a new iron spiral staircase.

After the hurricane Franklin Ponte, formerly an assistant at Boston Light, went to Palmer's Island Light as a temporary keeper. Ponte's nephew, Joseph Ponte, served as an assistant. All that was left was the lighthouse tower and the oil house, and Joseph Ponte said that he and his uncle lived for a almost a month in the lighthouse before the Coast Guard sent a garage that was converted into living quarters. The light was automated in 1941; Martin Maloney was the last keeper .

With the construction of a massive hurricane wall in New Bedford Harbor in 1963 the lighthouse was deemed useless. Palmers Island, adjacent to the new wall, became more easily accessible to lighthouse seekers and vandals alike. The island passed through various owners, including radio station WBSM. The tower was burned by arsonists in 1966, gutting the interior and practically destroying the lantern room.

In 1978 ownership of Palmers Island went from Norlantic Diesel to the City of New Bedford, and local resident Dr. John O'Toole mounted a preservation effort. New Bedford youngsters picked up 20 tons of trash and debris from the island, which they converted into $300 for the lighthouse fund. A new fiberglass lantern was constructed to replace the badly burned one, and a 500-pound steel door was installed. The New Bedford Fire Department contributed a new iron spiral staircase.

After another renovation in 1989, the lighthouse soon fell victim to more vandalism. It remained dark through most of the 1990s.

During the 1989 renovation

In April 1999, Hillary Rodham Clinton named New Bedford an official Millennium Community of the White House Millenium Council. The national theme of the Millennium Council is to "Honor the Past and Imagine the Future." It was decided that restoring and relighting Palmer's Island Lighthouse would be one of the city's Millennium projects. Arthur P. Motta, Jr., the city's Director of Tourism and Marketing, was also an important force in the restoration effort.

The badly damaged lantern room was removed on July 20, 1999, and taken to the city's wastewater division. Welder Jose Pereira rebuilt the lantern, while preserving the original metal frame. The four-foot-high, seven-foot-diameter lantern was reinstalled on August 25. The tower was repainted by a crew provided by the Bristol County Sheriff Department's Pre-Release Program, under the direction of volunteer Peter Duff. A new solar-powered beacon was installed, with a 250mm clear acrylic lens. The light now has a signature of two seconds on, six seconds off, and is visible for eight nautical miles. The new lighting apparatus was paid for with donated funds.

The badly damaged lantern room was removed on July 20, 1999, and taken to the city's wastewater division. Welder Jose Pereira rebuilt the lantern, while preserving the original metal frame. The four-foot-high, seven-foot-diameter lantern was reinstalled on August 25. The tower was repainted by a crew provided by the Bristol County Sheriff Department's Pre-Release Program, under the direction of volunteer Peter Duff. A new solar-powered beacon was installed, with a 250mm clear acrylic lens. The light now has a signature of two seconds on, six seconds off, and is visible for eight nautical miles. The new lighting apparatus was paid for with donated funds.

A large crowd gathered on the state pier on the pleasant evening of August 30, 1999, to witness the relighting of Palmer's Island Light, 150 years almost to the minute after its first lighting in 1849.

One of the whaleboats during the relighting ceremony

Anne Blum Brengle, Director of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society and New Bedford Whaling Museum, recounted the drama and tragedy of Palmer's Island's history.

In a dramatic tribute to the city's past as the whaling capital of the nation, three crews from the Whaling City Rowing Club took part in the relighting ceremony. Mayor Frederick M. Kalisz, Jr., handed out lighted oil lanterns to the crews on board the whaleboats Herman Melville, Flying Fish, and Skylark.

In a dramatic tribute to the city's past as the whaling capital of the nation, three crews from the Whaling City Rowing Club took part in the relighting ceremony. Mayor Frederick M. Kalisz, Jr., handed out lighted oil lanterns to the crews on board the whaleboats Herman Melville, Flying Fish, and Skylark.

The three boats made their way to the island. As the crowd watched quietly, Mayor Kalisz waved another lantern in the air and the lighthouse soon began to flash.

"This shall be remembered by the citizens of New Bedford as the day they reaffirmed their ties to the sea, and indeed, to the world," said Mayor Kalisz (right) in a proclamation that is on display at the lighthouse and in City Hall.

The lighthouse again fell into disrepair in the ensuing years, but another renovation was carried out in 2014. The work included the removal and restoration of the lantern, the cleaning of debris from inside the lighthouse, the repointing of the interior and exterior walls, repair of the stairs, the installation of new windows, and the installation of new solar powered lighting apparatus.

Palmers Island is accessible at low tide from New Bedford's hurricane wall. The lighthouse can be seen from the New Bedford Whaling Museum and other spots on shore, and the ferry to Cuttyhunk Island passes the island, as does a harbor tour offered daily in season.

The lighthouse again fell into disrepair in the ensuing years, but another renovation was carried out in 2014. The work included the removal and restoration of the lantern, the cleaning of debris from inside the lighthouse, the repointing of the interior and exterior walls, repair of the stairs, the installation of new windows, and the installation of new solar powered lighting apparatus.

Palmers Island is accessible at low tide from New Bedford's hurricane wall. The lighthouse can be seen from the New Bedford Whaling Museum and other spots on shore, and the ferry to Cuttyhunk Island passes the island, as does a harbor tour offered daily in season.

Keepers: William Sherman (1849-1853); Charles D. Tuell (1853-1861); George Cowie (1872-1891); Arthur Small (1922-1938); Franklin Ponte (c. 1939-1940); Martin Maloney (c.1941).