History of Spring Point Ledge Light, South Portland, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Spring Point Ledge is a dangerous obstruction on the west side of the main shipping channel from the south into Portland Harbor. Many vessels ran aground on the ledge before requests from seven steamship companies in 1891 convinced the federal government to build a lighthouse. The steamship companies had carried more than 500,000 passengers through the area during the previous year.

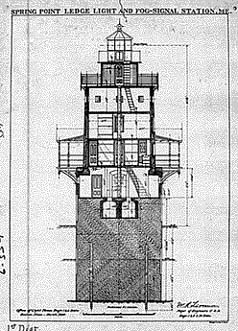

Spring Point Ledge Light is a fairly typical "sparkplug" style lighthouse of the period, built on a cylindrical cast-iron caisson. Unlike many of this type, however, the tower is built of brick rather than cast-iron.

The contractor who built the lighthouse, Thomas Dwyer, was also responsible for some prominent buildings in New York City, including a wing of the Metropolitan Museum and several buildings at City College.

The lighthouse was paid for by two appropriations totaling $45,000. It was first lighted May 24, 1897 by Keeper William A. Lane. The 54-foot lighthouse has a storeroom and cistern in the basement, topped by four levels including a keeper's office and two levels of living quarters.

The lantern was fitted with a fifth-order Fresnel lens. An oil room in the basement contained a 239-gallon tank for the kerosene that fueled the light in its early days, until it was electrified in 1934. A fog bell hung on the side of the tower, which sounded a double blow every 12 seconds by means of a striking mechanism powered by a clockwork mechanism with 800 pounds of weights.

The contractor who built the lighthouse, Thomas Dwyer, was also responsible for some prominent buildings in New York City, including a wing of the Metropolitan Museum and several buildings at City College.

The lighthouse was paid for by two appropriations totaling $45,000. It was first lighted May 24, 1897 by Keeper William A. Lane. The 54-foot lighthouse has a storeroom and cistern in the basement, topped by four levels including a keeper's office and two levels of living quarters.

The lantern was fitted with a fifth-order Fresnel lens. An oil room in the basement contained a 239-gallon tank for the kerosene that fueled the light in its early days, until it was electrified in 1934. A fog bell hung on the side of the tower, which sounded a double blow every 12 seconds by means of a striking mechanism powered by a clockwork mechanism with 800 pounds of weights.

Spring Point Ledge Light was a "stag station," with a male keeper and assistant keeper living inside the tower.

Keepers had to be creative in their means of exercise. Somebody figured that it took 56 jogs around the tower's main deck to make one mile. Once, a keeper was running laps in this fashion and forgot to close a trap door. He slipped through the opening and only a ladder prevented him from falling 17 feet to a rock ledge and swirling waves.

In its early years, the lighthouse's foundation was battered and damaged by ice. Granite blocks were piled around the foundation to protect it, and there have been no further problems.

Daniel J. Doyle was keeper from 1915 to 1918. He occupied his spare time by playing cribbage and building ship models. Keeper Doyle had a family living in Portland. His schedule called for him to come ashore after two weeks at the lighthouse, but stormy weather sometimes prevented him from leaving the station for up to two months at a stretch.

Doyle's daugher, Barbara Ward, told the Portland Press Herald, "It was a rough life. It was confining... and you had to be really alert and pay attention to what you were doing." Just the same, she says, "he enjoyed every minute of it."

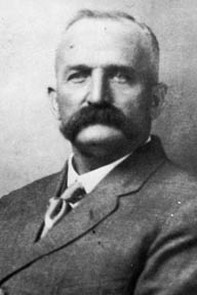

One of the light's best known keepers was Augustus Aaron "Gus" Wilson, a native of Tremont, Maine. He earned a living as a fisherman and boatbuilder before joining the Lighthouse Service at the age of 50. His first light station was Great Duck Island. When he arrived there, he found there was no Parchessi board, so he made one out of wood. After time at Great Duck Island, Marshall Point, Goose Rocks, and Cape Elizabeth, he came to Spring Point Ledge Light in 1917 and remained there until 1934.

In its early years, the lighthouse's foundation was battered and damaged by ice. Granite blocks were piled around the foundation to protect it, and there have been no further problems.

Daniel J. Doyle was keeper from 1915 to 1918. He occupied his spare time by playing cribbage and building ship models. Keeper Doyle had a family living in Portland. His schedule called for him to come ashore after two weeks at the lighthouse, but stormy weather sometimes prevented him from leaving the station for up to two months at a stretch.

Doyle's daugher, Barbara Ward, told the Portland Press Herald, "It was a rough life. It was confining... and you had to be really alert and pay attention to what you were doing." Just the same, she says, "he enjoyed every minute of it."

One of the light's best known keepers was Augustus Aaron "Gus" Wilson, a native of Tremont, Maine. He earned a living as a fisherman and boatbuilder before joining the Lighthouse Service at the age of 50. His first light station was Great Duck Island. When he arrived there, he found there was no Parchessi board, so he made one out of wood. After time at Great Duck Island, Marshall Point, Goose Rocks, and Cape Elizabeth, he came to Spring Point Ledge Light in 1917 and remained there until 1934.

Wilson gained wide fame as one of New England’s most accomplished carvers of wooden bird decoys.

Gus Wilson

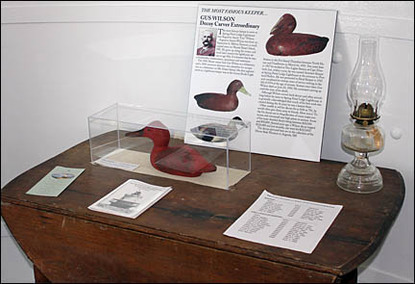

He carved a variety of ducks, shore birds, seagulls, and songbirds; it’s been estimated that his total production was in excess of 5,000 carvings. “Gus whittled every spare moment,” said Fred Anderson, a local man who spent much time with the keeper.

Wilson carved duck decoys by the hundreds and sold them to a store in Portland for 75 cents each. He was renowned for his carving skill and imagination, and his work became highly collectible. One of Wilson’s decoys fetched $195,500 at a 2005 auction. His work has been displayed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Spring Point Ledge Light was electrified in 1934. For some years, the keepers at Spring Point Ledge also monitored nearby Portland Breakwater Light.

John Attleson, an Iowa native who served as a Coast Guard keeper for about two years during World War II, later told stories about how he hated rowing through the pack ice in winter to get supplies. Attleson was wed during his stint at Spring Point.

Wilson carved duck decoys by the hundreds and sold them to a store in Portland for 75 cents each. He was renowned for his carving skill and imagination, and his work became highly collectible. One of Wilson’s decoys fetched $195,500 at a 2005 auction. His work has been displayed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Spring Point Ledge Light was electrified in 1934. For some years, the keepers at Spring Point Ledge also monitored nearby Portland Breakwater Light.

John Attleson, an Iowa native who served as a Coast Guard keeper for about two years during World War II, later told stories about how he hated rowing through the pack ice in winter to get supplies. Attleson was wed during his stint at Spring Point.

In 1951, a 900-foot breakwater was constructed with 50,000 tons of granite, joining the lighthouse to the mainland.

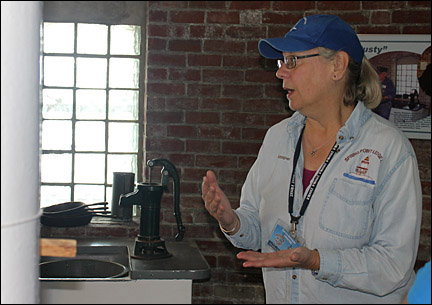

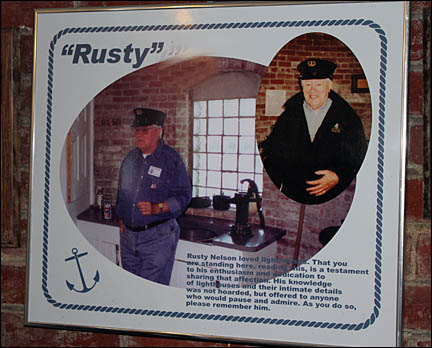

A display in the lighthouse tells the story of Gus Wilson and his decoys

The light was automated and destaffed in 1960. In the 1990s, under the Maine Lights Program coordinated by the Island Institute of Rockland, Spring Point Ledge Light was expected to be transferred from the Coast Guard to some other group.

The City of South Portland applied to co-own the property with Southern Maine Technical College, but in October 1997 the city council voted to withdraw the application after 90 minutes of debate. A handicapped-rights activist had threatened to take the city to court if the lighthouse wasn't made handicapped-accessible, which would have cost approximately $250,000.

In March 1998, the Spring Point Museum (now the Portland Harbor Museum) was allowed to make a late application to the Maine Lights Selection Committee. The museum put together the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust, made up of local residents, business people, museum members and city representatives.

The City of South Portland applied to co-own the property with Southern Maine Technical College, but in October 1997 the city council voted to withdraw the application after 90 minutes of debate. A handicapped-rights activist had threatened to take the city to court if the lighthouse wasn't made handicapped-accessible, which would have cost approximately $250,000.

In March 1998, the Spring Point Museum (now the Portland Harbor Museum) was allowed to make a late application to the Maine Lights Selection Committee. The museum put together the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust, made up of local residents, business people, museum members and city representatives.

The chairman of the museum's board of directors answered the handicapped access issue by pointing out that the Army Corps of Engineers owns the breakwater, so the owner of the lighthouse is not legally reponsible for access.

Left: U.S. Coast Guard photo, circa 1950. Notice that the breakwater hadn't been completed.

On April 28, 1998, the Maine Lights Selection Committee announced the transfer of Spring Point Ledge Light to the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust.

On Saturday, May 22, 1999, Spring Point Ledge Light was opened to the public for the first time in its history. About 500 people visited that day, braving a cool wind that swept the breakwater.

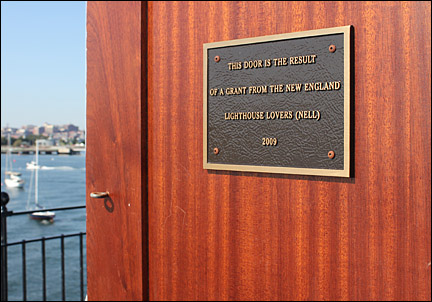

In 2004, a six-year effort by the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust culminated in the replacement of the badly deteriorated iron canopy over the structure's lower gallery. Atlantic Mechanical Inc. of Wiscasset, Maine, completed the overhaul in July 2004.

On April 28, 1998, the Maine Lights Selection Committee announced the transfer of Spring Point Ledge Light to the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust.

On Saturday, May 22, 1999, Spring Point Ledge Light was opened to the public for the first time in its history. About 500 people visited that day, braving a cool wind that swept the breakwater.

In 2004, a six-year effort by the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust culminated in the replacement of the badly deteriorated iron canopy over the structure's lower gallery. Atlantic Mechanical Inc. of Wiscasset, Maine, completed the overhaul in July 2004.

During the first stage of the $52,000 job, Atlantic Mechanical workers removed all 32 plates of the canopy, then cleaned and painted all the supporting rafters and fittings.

A worker from Atlantic Mechanical in 2004

New panels made of steel were fabricated using the originals as templates, and the panels were powder coated using a high heat process prior to installation. When the lighthouse was built in 1897, the canopy plates were installed using rivets. Since that type of construction isn't done anymore, the new panels were installed with stainless steel bolts that look much like the earlier rivets.

The canopy plates were refurbished and the lighthouse was painted in 2011. There are plans in the works to restore the caisson.

Spring Point Ledge Light is easily reached by land, and tour boats and ferries leaving Portland pass the lighthouse. The campus of Southern Maine Community College adjoins the property.

The canopy plates were refurbished and the lighthouse was painted in 2011. There are plans in the works to restore the caisson.

Spring Point Ledge Light is easily reached by land, and tour boats and ferries leaving Portland pass the lighthouse. The campus of Southern Maine Community College adjoins the property.

PLEASE NOTE: The following list of keepers is not complete. It is a work in progress, and any additional information is welcomed and appreciated; you can email me at [email protected]. If you copy this list to another site, you do so at your own risk. I can't guarantee its accuracy.

Keepers: William A. Lane (1897-1901); William Harry Phillips (assistant, 1897-1898); Harris S. Grant (first assistant 1898-1901, head keeper 1901-1902); Frank Cotton (Cullen?) (1902); Charles E. B. Stanley (first assistant 1902, head keeper 1902-1908?); Charles A. Burke (first assistant, 1901-1902); Joseph W. Cameron (first assistant 1902-1904); Jerome C. Brawn (first assistant 1904); Otto A. Wilson (1908-1931); Leroy Elwell (first assistant, 1908-1909; principal keeper c. 1935-36); Edward Merritt (first assistant, 1909-? ); Daniel J. Doyle (1915-1918); John W. Cameron (assistant. c. 1920s); Augustus A. Wilson (assistant 1918-1931, principal keeper 1931-1934); Douglas Larrabee (c. 1936-?); John Attleson (Coast Guard, c. 1943-1945); Ralph Norwood (Coast Guard, 1951-1954); Joseph Bakken (Coast Guard, 1954-?)

Left: The old fog bell is on display on the gallery outside the lighthouse, next to the modern electronic foghorn.

Left: The old fog bell is on display on the gallery outside the lighthouse, next to the modern electronic foghorn.