History of Cape Neddick "Nubble" Light, York, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

By following a cart-track for a quarter of an hour one comes to the canal, a stone's throw across, dividing the cape from the Nubble Rock. On the top of this bare crag the lighthouse-keeper's dwelling and fog signal stand out bold and sharp against the blue sky. At the east, a clump of blanched ledges stretches off... This prospect comprises everything between Cape Ann and Cape Elizabeth in clear weather, and is every way admirable. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

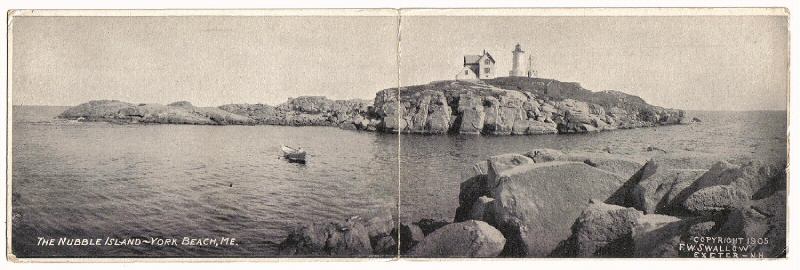

Late 1800s (National Archives)

The "Nubble" is a small, rocky island a short distance off the eastern point of Cape Neddick, about two miles north of the entrance to the York River and York Harbor. In 1602, explorer Bartholomew Gosnold met with local Indians on the island and dubbed it "Savage Rock."

The placement of a lighthouse on the Nubble had been recommended by many local mariners since 1807. An 1837 proposal was rejected on the grounds that there were already enough lights in the vicinity. Even after the wreck of the bark Isidore in 1842, north of the Nubble near Bald Head Cliff, it still took nearly four more decades before the lighthouse was established. The Isidore, according to legend, still reappears as a ghost ship with a phantom crew.

The placement of a lighthouse on the Nubble had been recommended by many local mariners since 1807. An 1837 proposal was rejected on the grounds that there were already enough lights in the vicinity. Even after the wreck of the bark Isidore in 1842, north of the Nubble near Bald Head Cliff, it still took nearly four more decades before the lighthouse was established. The Isidore, according to legend, still reappears as a ghost ship with a phantom crew.

Congress appropriated $15,000 for the building of a lighthouse on the Nubble in 1876. The 41-foot cast-iron tower, lined with brick, was first illuminated on July 1, 1879.

Early postcard view showing the original fog bell tower

At first, the lighthouse was painted reddish-brown, showing a fixed red light through a fourth-order Fresnel lens. The lighthouse still exhibits a red light, but the tower has been painted white since 1902.

The distinctive red oil house was built in 1902, and the walkway connecting the lighthouse to the keeper's house was added in 1911.

The station originally had a fog bell operated by automatic striking machinery. The skeleton frame bell tower was replaced in 1911 by a white pyramidal tower, itself torn down in 1961.

For a time, the Nubble's 3,000 pound fog bell could be heard by the keepers at Boon Island six miles away. The bell was later replaced by a diaphragm horn.

The distinctive red oil house was built in 1902, and the walkway connecting the lighthouse to the keeper's house was added in 1911.

The station originally had a fog bell operated by automatic striking machinery. The skeleton frame bell tower was replaced in 1911 by a white pyramidal tower, itself torn down in 1961.

For a time, the Nubble's 3,000 pound fog bell could be heard by the keepers at Boon Island six miles away. The bell was later replaced by a diaphragm horn.

Nathaniel Otterson was the first keeper. His replacement, Brackett Lewis, formerly assistant keeper of Whaleback Light, was keeper from 1885 to 1904, the longest stint of any keeper at the Nubble. While Lewis was keeper, his daughter, Hattie, married Charles Billings in the lantern room.

The next keeper, William Brooks, previously at Boon Island and White Island, picked up extra cash by ferrying sightseers and fishermen to the island for ten cents apiece. This was not appreciated by Brooks' superiors, and the keeper soon "resigned."

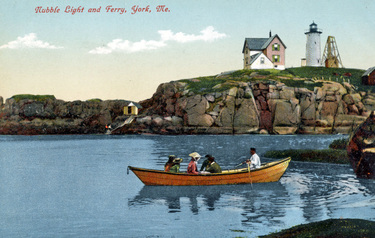

Left: Early postcard view showing a keeper ferrying visitors to the Nubble.

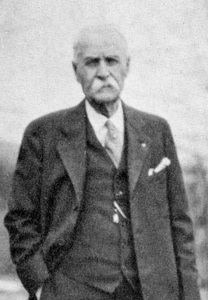

James Burke of Portsmouth became keeper in 1912. One of his sons, Charles Burke, was keeper at Wood Island Light, just up the coast off Biddeford Pool. James Burke had gone to sea at the age of 14 and eventually skippered fishing vessels before turning to lighthouse keeping.

Left: Early postcard view showing a keeper ferrying visitors to the Nubble.

James Burke of Portsmouth became keeper in 1912. One of his sons, Charles Burke, was keeper at Wood Island Light, just up the coast off Biddeford Pool. James Burke had gone to sea at the age of 14 and eventually skippered fishing vessels before turning to lighthouse keeping.

Like many lighthouse families, the Burkes kept a cow and chickens on the island. Burke went duck hunting and fishing to supplement his family’s food supply. Lobsters, crabs, and mussels were also plentiful near the island.

James Burke (courtesy of William O. Thomson)

In a letter to author Clifford Shattuck, James Burke’s daughter Lucy Glidden Burke Steffen later recalled other details of life on the Nubble:

We all had lots of work to do, as everything had to be immaculate throughout the house as well as the lighthouse tower. . . . We had lots of company, weather permitting. Many of my schoolmates used to enjoy coming over to the Nubble, some just to spend the day, some to spend the night or possibly to stay for a few days. Sometimes the sea got rough and they HAD to stay. We had an organ in the living room which I used to play and we all had such good times singing the old songs. Our home was a very comfortable six-room house, having a very pleasant living room, a nice size dining room, a large kitchen with pantry, and three bedrooms upstairs. But, of course, no bathroom. We had a large parlor stove which seemed to heat most of the house very well. Even though a severe storm might be blowing up outside, we were nice and cozy.

At low tide, it was sometimes possible to walk between the Nubble and the mainland. Lucy recalled being carried piggyback by her father, who would wear hip boots for the occasion, across the bar. She also recalled the large numbers of birds that would fly into the tower at night; the family sometimes had to rake up hundreds of them that lay dead on the ground in the morning.

We all had lots of work to do, as everything had to be immaculate throughout the house as well as the lighthouse tower. . . . We had lots of company, weather permitting. Many of my schoolmates used to enjoy coming over to the Nubble, some just to spend the day, some to spend the night or possibly to stay for a few days. Sometimes the sea got rough and they HAD to stay. We had an organ in the living room which I used to play and we all had such good times singing the old songs. Our home was a very comfortable six-room house, having a very pleasant living room, a nice size dining room, a large kitchen with pantry, and three bedrooms upstairs. But, of course, no bathroom. We had a large parlor stove which seemed to heat most of the house very well. Even though a severe storm might be blowing up outside, we were nice and cozy.

At low tide, it was sometimes possible to walk between the Nubble and the mainland. Lucy recalled being carried piggyback by her father, who would wear hip boots for the occasion, across the bar. She also recalled the large numbers of birds that would fly into the tower at night; the family sometimes had to rake up hundreds of them that lay dead on the ground in the morning.

James Burke’s second wife died during his stay at the Nubble, and the government provided a lighthouse tender to transport the family to Boothbay Harbor for the funeral. During World War I, the Burkes were joined on the Nubble by military personnel who kept watch for enemy submarines. The light was dimmed on some nights and extinguished on others, to confuse “possible submersibles" in the vicinity.

Fairfield Moore (courtesy of William O. Thomson)

After he retired in 1919, Burke opened a small fish and bait shop at York Beach. William Richardson, the next keeper, stayed until 1921. During his relatively brief stay, Richardson’s son died of croup. Richardson was discharged for ferrying passengers to the Nubble for a fee.

Fairfield Moore, previously at Rockland Breakwater Light, was keeper from 1921 to 1928. The first birth of a child at the Nubble occurred on August 23, 1923, when Moore’s daughter, Phyllis Moore Searles, delivered a baby girl, Helen.

In July 1926, it was reported that the fog bell tower was moved about four feet from its foundation by a powerful storm, leaving it on the brink of a precipice. Moore didn’t dare sound the bell because he feared that the vibration could plunge the bell and tower into the sea. Repairs were soon completed.

On March 20, 1927, the keeper’s daughter Eva Moore Kimball went into labor during a severe snowstorm. Keeper Moore rowed across the channel and picked up a local doctor. The two men returned to the Nubble just in time for the last seconds of the birth of Eva’s daughter, Barbara.

Barbara Kimball (Finnemore) lived at the lighthouse until she was six. Her favorite memory was accompanying her grandfather to the top of the tower to light the lamp.

Fairfield Moore returned to Rockland Breakwater Light in 1928 and was succeeded at the Nubble by Edmund Howe, who was had previously been at Great Duck Island Light. During his tenure, Howe married his housekeeper, Emily Williams, in the living room of the keeper’s house.

Fairfield Moore, previously at Rockland Breakwater Light, was keeper from 1921 to 1928. The first birth of a child at the Nubble occurred on August 23, 1923, when Moore’s daughter, Phyllis Moore Searles, delivered a baby girl, Helen.

In July 1926, it was reported that the fog bell tower was moved about four feet from its foundation by a powerful storm, leaving it on the brink of a precipice. Moore didn’t dare sound the bell because he feared that the vibration could plunge the bell and tower into the sea. Repairs were soon completed.

On March 20, 1927, the keeper’s daughter Eva Moore Kimball went into labor during a severe snowstorm. Keeper Moore rowed across the channel and picked up a local doctor. The two men returned to the Nubble just in time for the last seconds of the birth of Eva’s daughter, Barbara.

Barbara Kimball (Finnemore) lived at the lighthouse until she was six. Her favorite memory was accompanying her grandfather to the top of the tower to light the lamp.

Fairfield Moore returned to Rockland Breakwater Light in 1928 and was succeeded at the Nubble by Edmund Howe, who was had previously been at Great Duck Island Light. During his tenure, Howe married his housekeeper, Emily Williams, in the living room of the keeper’s house.

James Burke and his family had left their cat behind because he had come so attached to the Nubble, and the big tabby weighed 19 pounds by the time Eugene Coleman arrived as keeper in 1930.

Sambo Tonkus, also known as Mr. T, became well known to locals and tourists alike for his mousing and swimming prowess. Three or four times a day, he would swim to the mainland to hunt rodents hiding among the rocks.

During the Colemans’ stay, the first indoor toilet was installed, and electricity came to the Nubble in 1938. During World War II, the light was extinguished and a lookout tower was built on the island. A contingent of Coast Guardsmen kept a 24-hour eye out for German U-boats. A U-boat sighted in 1943 just to the east of the Nubble was subsequently sunk by a depth charge southwest of Boon Island.

Right: Eugene Coleman and Sambo Tonkus. (Courtesy of William O. Thomson)

The historian Edward Rowe Snow, in his book Famous New England Lighthouses, wrote that on one occasion, Eugene Coleman was rowing across the channel near the Nubble with his wife, a friend, and a load of groceries, when the boat capsized. “The dory went over and the keeper had a busy five minutes, trying to rescue his wife, his friend, and the groceries,” wrote Snow, “but all ended happily except for minor injuries to the groceries.”

During the Colemans’ stay, the first indoor toilet was installed, and electricity came to the Nubble in 1938. During World War II, the light was extinguished and a lookout tower was built on the island. A contingent of Coast Guardsmen kept a 24-hour eye out for German U-boats. A U-boat sighted in 1943 just to the east of the Nubble was subsequently sunk by a depth charge southwest of Boon Island.

Right: Eugene Coleman and Sambo Tonkus. (Courtesy of William O. Thomson)

The historian Edward Rowe Snow, in his book Famous New England Lighthouses, wrote that on one occasion, Eugene Coleman was rowing across the channel near the Nubble with his wife, a friend, and a load of groceries, when the boat capsized. “The dory went over and the keeper had a busy five minutes, trying to rescue his wife, his friend, and the groceries,” wrote Snow, “but all ended happily except for minor injuries to the groceries.”

The lighthouse has a long history as a tourist destination. In 1930, Coleman recorded over 1,000 visitors in his guest register, including guests from 11 nations and 32 states. The Colemans moved on to Nauset Light on Cape Cod in 1943, and thereafter Coast Guard keepers staffed the Nubble. It remained a family station.

Ricky Winchester riding in the bucket in 1967.

The Coast Guard keeper from 1948 to 1951, Wilbur Brewster, had a parrot whose home was a cage in the living room. According to the lighthouse historian William O. Thomson, the parrot enjoyed carrying on conversations with visitors. Its favorite phrase was, “I’ll have a cup of coffee.”

Boyd J. Davis of the Coast Guard was keeper 1961-62, and he was there for the removal of the fog bell tower in 1961. The following message was received from his son Steven Davis in February 2020:

I have many fond memories of our time at the Nubble, including me and my two brothers going to school by boat. My father, Boyd J. Davis USCG, was the keeper during our stay there in 1961 and 1962. I was there the morning that they blew the footings from the bell tower, and was glad to see it go, as dad would press my brother and I into cranking the trip weights to the top of it when he thought we needed to burn off a little energy.

Twenty-six-year-old David Winchester arrived as the Coast Guard keeper in 1966. In November, he took his pregnant wife P. Jaye to the mainland and she caught a Greyhound bus to Portland, Maine. Their third child, Wendianne, was born the next day.

P. Jaye Winchester later described the family's time at the Nubble Light as the "best time" of her life. "Never a moment were we bored," she said. David once broke his big toe and couldn't climb the lighthouse stairs for a period, and P. Jaye tended the light. The TV got only three channels, but the children explored on the island and the whole family did lots of reading. "It was just a utopia, a wonderful place for the children," said P. Jaye.

John Reidy was a relief keeper 1966-67. He later wrote the following:

Getting supplies out to the Nubble was its own challenge. There was a peapod boat there, but it was seldom used, again because the ramp was not well sheltered. Further, there was not a dock on the mainland, available close by. Instead, a cable car ran from the mainland out to the island. This car was little more than a wooden box, about five feet square. A cable was suspended on telephone poles that were installed at both ends, and had platforms in place to load and unload whatever was needed.

When the extreme low tides of the moon occurred, it was possible to walk over the exposed rocks to get from the mainland to the island. This was not often possible, and was dangerous when it was, due to the slippery seaweed present. I recall one time when the refrigerator in the keeper’s kitchen failed and required replacement. This equipment exchange was made via the cable car. Moving an upright refrigerator on a suspended cable car was certainly a very tense and frightening experience! Fortunately this was done during the summer so hauling the new refrigerator from the cable car, uphill to the lighthouse, was able to be accomplished with only the force of gravity to overcome. Also of note, movement of the cable car was done by hand over hand, not by means of any electric motors.

The bucket suspended from a cable from the mainland to the island, installed in the 1950s, was not intended for the transport of people; it was intended for the transportation of supplies. The Winchesters used it creatively. When they returned to the island after Wendianne was born, P. Jaye and her baby went across in the bucket.

"It wasn't that big a deal," she recalled later, in an article on Seacoastonline.com. "We were so used to it. (David) took the suitcases and all the baby formula and went to the island (in the boat). There was no baby life jacket for Wendy. She and I climbed into the bucket. I'll never forget, two elderly ladies saw us. The gasps were deafening. I climbed in. I was just so anxious to get home. He pulled us over. He secured the box. There we were, home. I waved to the ladies, 'we're safe.' They waved back, God love 'em."

Boyd J. Davis of the Coast Guard was keeper 1961-62, and he was there for the removal of the fog bell tower in 1961. The following message was received from his son Steven Davis in February 2020:

I have many fond memories of our time at the Nubble, including me and my two brothers going to school by boat. My father, Boyd J. Davis USCG, was the keeper during our stay there in 1961 and 1962. I was there the morning that they blew the footings from the bell tower, and was glad to see it go, as dad would press my brother and I into cranking the trip weights to the top of it when he thought we needed to burn off a little energy.

Twenty-six-year-old David Winchester arrived as the Coast Guard keeper in 1966. In November, he took his pregnant wife P. Jaye to the mainland and she caught a Greyhound bus to Portland, Maine. Their third child, Wendianne, was born the next day.

P. Jaye Winchester later described the family's time at the Nubble Light as the "best time" of her life. "Never a moment were we bored," she said. David once broke his big toe and couldn't climb the lighthouse stairs for a period, and P. Jaye tended the light. The TV got only three channels, but the children explored on the island and the whole family did lots of reading. "It was just a utopia, a wonderful place for the children," said P. Jaye.

John Reidy was a relief keeper 1966-67. He later wrote the following:

Getting supplies out to the Nubble was its own challenge. There was a peapod boat there, but it was seldom used, again because the ramp was not well sheltered. Further, there was not a dock on the mainland, available close by. Instead, a cable car ran from the mainland out to the island. This car was little more than a wooden box, about five feet square. A cable was suspended on telephone poles that were installed at both ends, and had platforms in place to load and unload whatever was needed.

When the extreme low tides of the moon occurred, it was possible to walk over the exposed rocks to get from the mainland to the island. This was not often possible, and was dangerous when it was, due to the slippery seaweed present. I recall one time when the refrigerator in the keeper’s kitchen failed and required replacement. This equipment exchange was made via the cable car. Moving an upright refrigerator on a suspended cable car was certainly a very tense and frightening experience! Fortunately this was done during the summer so hauling the new refrigerator from the cable car, uphill to the lighthouse, was able to be accomplished with only the force of gravity to overcome. Also of note, movement of the cable car was done by hand over hand, not by means of any electric motors.

The bucket suspended from a cable from the mainland to the island, installed in the 1950s, was not intended for the transport of people; it was intended for the transportation of supplies. The Winchesters used it creatively. When they returned to the island after Wendianne was born, P. Jaye and her baby went across in the bucket.

"It wasn't that big a deal," she recalled later, in an article on Seacoastonline.com. "We were so used to it. (David) took the suitcases and all the baby formula and went to the island (in the boat). There was no baby life jacket for Wendy. She and I climbed into the bucket. I'll never forget, two elderly ladies saw us. The gasps were deafening. I climbed in. I was just so anxious to get home. He pulled us over. He secured the box. There we were, home. I waved to the ladies, 'we're safe.' They waved back, God love 'em."

David and P. Jaye Winchester got into the habit of putting their son Ricky in the bucket each morning to send him on his way to school. P. Jaye later said that she thought the bucket was safer than the boat. "There were a lot of mornings Rick would not have been able to go to school in that boat (because of) the swell. You needed to bring the boat in at a slant. You had to count the waves to get up on those rocks. Otherwise, you would have been swamped. I felt very safe (in the bucket)," she said.

A photographer snapped a picture of seven-year-old Ricky Winchester in the bucket, and the photo appeared widely in newspapers. A woman also painted a scene of the boy in the bucket, and it won the York Harbor Art Show.

The story later inspired a children's book, Trouble at Nubble Light by Katherine Bailey.

A photographer snapped a picture of seven-year-old Ricky Winchester in the bucket, and the photo appeared widely in newspapers. A woman also painted a scene of the boy in the bucket, and it won the York Harbor Art Show.

The story later inspired a children's book, Trouble at Nubble Light by Katherine Bailey.

The district commander saw the photo in a Boston paper. An arrangement was made for the child to board on the mainland during the week. Soon after that, it became policy that families with school-age children were not sent to the Nubble.

The "bucket" circa 2003.

The fourth-order Fresnel lens is not the original one, but is an 1891 lens moved from another station in 1928. The original lens had been damaged in an explosion.

The great blizzard of February 6-7, 1978, washed out the Nubble's boathouse, which was replaced by the present structure.

The Nubble Light has probably appeared on more postcards, calendars, and other souvenirs than any other New England lighthouse, with the possible exception of Portland Head Light. In 1977, when NASA sent Voyager II into space to photograph the outer solar system, it was also loaded with artifacts designed to teach possible extraterrestrial civilizations about our planet. One of the images it carried was a picture of the Nubble Light.

Left: The finials on the gallery railing are miniature lighthouses.

The light was automated in 1987 and the last Coast Guard keeper, Russell Ahlgren, was removed. A crowd of more than 300 spectators witnessed the automation ceremonies on July 13 in dense fog. The station was leased to the town of York in 1989.

|

When the town took over, more than 300 unsolicited applications were received from people wanting to be live-in caretakers. The keeper's house remains unoccupied because of water and sewer issues.

Right: Russell and Brenda Ahlgren with their son, Chris, circa 1987. U.S. Coast Guard photo. In 1989, the town received a grant from the Maine Historic Preservation Committee for restoration work on the keeper's house. Two second story windows were removed and replaced by a larger window resembling the one originally installed. In November 1997, the people of York voted overwhelmingly to allow the town's selectmen to "adopt" the lighthouse. Under the Maine Lights Program coordinated by the Island Institute, the lighthouse officially became the property of the town in 1998. |

Parks and Recreation Director Mike Sullivan once said, "The park is absolutely jam packed every day. Part of the allure of Nubble Light is its mystical nature. You can't quite get there. You can almost reach it but you can't get there."

The welcome center at Sohier Park

Because it's easily reached by a drive of just a few minutes from popular York Beach, Sohier Park across from the Nubble is today visited by hundreds of thousands of people annually.

Sohier Park, incidentally, is named for William Davis Sohier, a lawyer from Boston who gave the land to the town of York in 1929. His father had bought the land for the fine duck hunting.

One of the most popular events of the year on the southern Maine coast is the annual Lighting of the Nubble, when the lighthouse and other buildings are illuminated with Christmas lights. The late November event is accompanied by holiday music and never fails to draw a large crowd.

Sohier Park, incidentally, is named for William Davis Sohier, a lawyer from Boston who gave the land to the town of York in 1929. His father had bought the land for the fine duck hunting.

One of the most popular events of the year on the southern Maine coast is the annual Lighting of the Nubble, when the lighthouse and other buildings are illuminated with Christmas lights. The late November event is accompanied by holiday music and never fails to draw a large crowd.

One of the Nubble's tireless volunteers, Verna Rundlett, originated a "Christmas in July" event, giving summer visitors a chance to view the station decorated just as it is at Christmastime. She also supervised the building of a welcome center at Sohier Park. The building, open seasonally, houses a gift shop and public restrooms.

Much work has taken place in recent years, both on the Nubble and at Sohier Park. Besides being easily viewed from Sohier Park, Cape Neddick Light can be seen from an excursion boat leaving Perkins Cove in Ogunquit, and from occasional lighthouse cruises leaving Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

|

Left and above, the band Nickel Creek shot a music video for the song "The Lighthouse's Tale" at the Nubble Light in October 2001

|

|

|

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Lighthouse Service keepers

Leander White (1879 - was reassigned before lighthouse was established); Simon Leighton (1879 - resigned due to illness); Nathaniel Otterson (1879-1885); Brackett Lewis (1885-1904); William M. Brooks (1904-1912); James Burke (1912-1919); William Richardson (1919-1921); Fairfield Moore (1921-1928); Edmund A. Howe (1928-1930); Truman J. Lathrop (1930); Eugene Coleman (1930-1943)

U.S. Coast Guard

Warren Alley (1943-?); Oscar M. "Tiny" Sparrow (c.1940s); Wilbur Brewster (1948-1951); Irving T. Sparrow (1951-1953); Robert McWilliams (1954-1955); Boyd L. Davis (c. 1950s); Bruce C. Reed (1957-1959); Bruce Creswell (c. 1959-1961); John Johnson (c.1961); Boyd J. Davis (1961-1962); R. Midgett (c.1964); Allan E. Wilson (c.1960s); John Reidy (relief keeper, 1965-1967); Alfred Paul Chadwick (Coast Guard, c. 1967); David K. Winchester (1966-1967); Alfred Paul Chadwick (August 1967 to August 1969); Scott Rome (c. 1969); Michael Carbino (c.1971-1973); Michael Hackett (1973-1975); Richard Harrison (1975-1977); Ronald O'Brien (1977-1979); John Terry (1979-1984); Robert French (1984-1986); Russell Ahlgren (1986-1987)

Lighthouse Service keepers

Leander White (1879 - was reassigned before lighthouse was established); Simon Leighton (1879 - resigned due to illness); Nathaniel Otterson (1879-1885); Brackett Lewis (1885-1904); William M. Brooks (1904-1912); James Burke (1912-1919); William Richardson (1919-1921); Fairfield Moore (1921-1928); Edmund A. Howe (1928-1930); Truman J. Lathrop (1930); Eugene Coleman (1930-1943)

U.S. Coast Guard

Warren Alley (1943-?); Oscar M. "Tiny" Sparrow (c.1940s); Wilbur Brewster (1948-1951); Irving T. Sparrow (1951-1953); Robert McWilliams (1954-1955); Boyd L. Davis (c. 1950s); Bruce C. Reed (1957-1959); Bruce Creswell (c. 1959-1961); John Johnson (c.1961); Boyd J. Davis (1961-1962); R. Midgett (c.1964); Allan E. Wilson (c.1960s); John Reidy (relief keeper, 1965-1967); Alfred Paul Chadwick (Coast Guard, c. 1967); David K. Winchester (1966-1967); Alfred Paul Chadwick (August 1967 to August 1969); Scott Rome (c. 1969); Michael Carbino (c.1971-1973); Michael Hackett (1973-1975); Richard Harrison (1975-1977); Ronald O'Brien (1977-1979); John Terry (1979-1984); Robert French (1984-1986); Russell Ahlgren (1986-1987)