History of Goat Island Light, Kennebunkport, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Cape Porpoise village is built around the shores of its harbor, which a cluster of large and small islands protects. On one of them stands the baby lighthouse of the coast. This harbor -- or perhaps we should say harbors, since there are two basins -- is remarkable for being the only one between Portsmouth and the Saco... -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

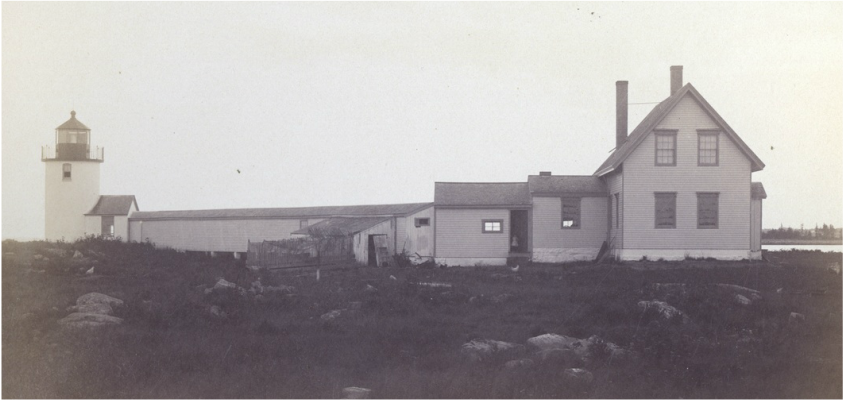

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Cape Porpoise was named by Capt. John Smith for a school of porpoises he saw there. Cape Porpoise is a village of the town of Kennebunkport, a popular tourist destination with a variety of shops and historic homes.

Established in August 1833 for $6,000, Goat Island Light was established to help guide mariners into the sheltered harbor at Cape Porpoise, a busy fishing center for many years. A 20-foot stone tower and dwelling were built, and John Lord of Kennebunk became the first keeper at a salary of $350 per year.

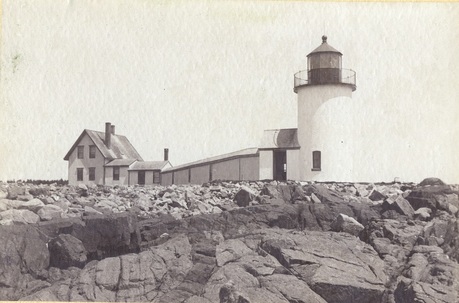

In 1859, the tower and house were rebuilt. The new tower received a fifth-order Fresnel lens.

For many years, the tower was connected to the 1 1/2-story house by a covered walkway. A boathouse was added in 1905 and an oil house in 1907.

Established in August 1833 for $6,000, Goat Island Light was established to help guide mariners into the sheltered harbor at Cape Porpoise, a busy fishing center for many years. A 20-foot stone tower and dwelling were built, and John Lord of Kennebunk became the first keeper at a salary of $350 per year.

In 1859, the tower and house were rebuilt. The new tower received a fifth-order Fresnel lens.

For many years, the tower was connected to the 1 1/2-story house by a covered walkway. A boathouse was added in 1905 and an oil house in 1907.

Dangerous rocks near Goat Island continued to claim vessels, including 46 between 1865 and 1920.

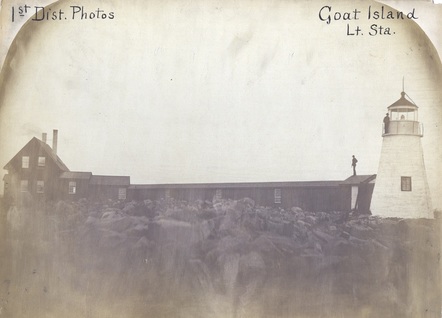

National Archives

There was not one death in all the wrecks, partly due to the keepers at Goat Island picking up survivors near the island. In 1930, a schooner, the Margery Austin, went aground near the lighthouse. Keeper James M. Anderson went out in rough seas and helped refloat the vessel.

George Wakefield of Saco kept the light from 1887 to 1921, the longest stint of any keeper at the station. Wakefield moonlighted as a harbor pilot and fisherman.

James M. Anderson was keeper in 1929 when the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, anchored their yacht near Goat Island during their honeymoon. Anderson and his family watched with binoculars as the Lindberghs moved around on the boat, and the keeper told a reporter that the lights were turned off on the yacht at 8:25 p.m.

George Wakefield of Saco kept the light from 1887 to 1921, the longest stint of any keeper at the station. Wakefield moonlighted as a harbor pilot and fisherman.

James M. Anderson was keeper in 1929 when the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, anchored their yacht near Goat Island during their honeymoon. Anderson and his family watched with binoculars as the Lindberghs moved around on the boat, and the keeper told a reporter that the lights were turned off on the yacht at 8:25 p.m.

Coast Guard Keeper Joseph Bakken, who lived on Goat Island with his wife and three children, told historian Edward Rowe Snow about his experience during a particularly severe storm in 1947. The waves washed over the island and damaged the walkway and the boat slip and ripped out a fence. In the commotion the family forgot about their dog and her newborn puppies.

Later that night, Bakken went into the cellar and found several feet of water. Floating in the seawater was the box that contained the dog and her puppies. All were safe and sound and the keeper brought them upstairs out of harm's way.

John Reidy was a relief keeper for the Coast Guard at Goat Island Light, Wood Island Light, and Cape Neddick Light, 1966-67. He later wrote the following reminiscences:

At Goat Island, the process of getting on and off the launch ramp was much easier than Wood island. The keeper and relief keeper launched the peapod boat easily and motored into the harbor at Cape Porpoise, where they tied up at the main lobster pier. Often the local lobstermen gave us a few fresh lobsters when we came ashore. This was always a treat!

Of the three light stations, Goat Island was by far the lowest in elevation. The winds of winter storms were sometimes ferocious enough to cause the dwelling to shudder. The spray from wind-driven waves breaking on the rocks on the eastern shore of the island would sometimes reach the house.

I always liked it when I was sent to Goat Island for duty. My grandparents had retired to a waterfront home in the inner harbor of Cape Porpoise. If the tide was high, I motored on up to the dock at their home. Grandma always had some sort of delicious fresh baked pies or cookies in here oven. Her yummy eats for a hungry bachelor Coast Guardsman were great, and I was always thankful that they were close by. In return, I watched over my grandfather, whenever he was fishing near the harbor entrance buoy.

Julie Owyang, whose brother Mark Brooke was the Coast Guard's officer in charge for two years in the 1970s, wrote the following note in January 2009:

I came and spent two weeks with them Christmas of '73. My Mom and Dad and I took the train up from western North Carolina to Boston, and Mark picked us up there. What a treat! I'll never forget the piles of lobster we had for dinner in the kitchen with the table covered with newspapers. We had kept them alive in the sink that had the saltwater faucet in it until it was time to cook them.

The Coast Guard initially planned to automate Goat Island Light in 1976. Local residents felt that having a keeper on Goat Island was important to protect the island and lighthouse station from vandalism, so the automation plans were postponed.

John Reidy was a relief keeper for the Coast Guard at Goat Island Light, Wood Island Light, and Cape Neddick Light, 1966-67. He later wrote the following reminiscences:

At Goat Island, the process of getting on and off the launch ramp was much easier than Wood island. The keeper and relief keeper launched the peapod boat easily and motored into the harbor at Cape Porpoise, where they tied up at the main lobster pier. Often the local lobstermen gave us a few fresh lobsters when we came ashore. This was always a treat!

Of the three light stations, Goat Island was by far the lowest in elevation. The winds of winter storms were sometimes ferocious enough to cause the dwelling to shudder. The spray from wind-driven waves breaking on the rocks on the eastern shore of the island would sometimes reach the house.

I always liked it when I was sent to Goat Island for duty. My grandparents had retired to a waterfront home in the inner harbor of Cape Porpoise. If the tide was high, I motored on up to the dock at their home. Grandma always had some sort of delicious fresh baked pies or cookies in here oven. Her yummy eats for a hungry bachelor Coast Guardsman were great, and I was always thankful that they were close by. In return, I watched over my grandfather, whenever he was fishing near the harbor entrance buoy.

Julie Owyang, whose brother Mark Brooke was the Coast Guard's officer in charge for two years in the 1970s, wrote the following note in January 2009:

I came and spent two weeks with them Christmas of '73. My Mom and Dad and I took the train up from western North Carolina to Boston, and Mark picked us up there. What a treat! I'll never forget the piles of lobster we had for dinner in the kitchen with the table covered with newspapers. We had kept them alive in the sink that had the saltwater faucet in it until it was time to cook them.

The Coast Guard initially planned to automate Goat Island Light in 1976. Local residents felt that having a keeper on Goat Island was important to protect the island and lighthouse station from vandalism, so the automation plans were postponed.

In the video above, recorded by Lisa Lassey in 2012, Charlie Worrell and his wife, Ursula, recall life on Goat Island circa 1970-72, when Worrell was the Coast Guard keeper.

Martin Cain, a Minnesota native, was the Coast Guard’s officer in charge from October 1975 until June 1978. Cain monitored the local buoys and recorded the weather four times daily. He switched on the foghorn when a lighted buoy almost two miles away was obscured by fog or storm.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

In a 1976 interview, Cain said he and his wife, Cathy, had to be more compatible than the average couple, but if they did have a fight, “One goes to one side of the island and the other goes to the other side and talks to the seagulls.”

Martin and Cathy Cain lived on the island with their young son, Martin J., infant son John, and two cats and a dog. The Cains were on the island for the memorable blizzard of February 6–7, 1978, which folded the covered walkway between the house and tower “like a big accordion” and swept it off the island. The Coast Guard removed the Cains from the island by helicopter a short time later.

At the end of his stay, Cain said, “We’ve seen a lot out here and for the most part we’ve enjoyed it, but we’re ready to leave.”

Mark Estee was the Coast Guard keeper 1978-80. He lived on the island with his wife, Kris, and their two young children, Nathaniel and Michelle. In an email in June 2011, Kris (Estee) Woodgate recalled life on the island:

It was such an adventure. We were quite young, early 20s, and from Wisconsin so we had never seen such a beautiful place ever. We were the ones who put in the new wooden walkway and cleaned up after the storm of 1978. The island was quite a mess. We had lots of company from Wisconsin; our relatives thought it was pretty awesome.

Martin and Cathy Cain lived on the island with their young son, Martin J., infant son John, and two cats and a dog. The Cains were on the island for the memorable blizzard of February 6–7, 1978, which folded the covered walkway between the house and tower “like a big accordion” and swept it off the island. The Coast Guard removed the Cains from the island by helicopter a short time later.

At the end of his stay, Cain said, “We’ve seen a lot out here and for the most part we’ve enjoyed it, but we’re ready to leave.”

Mark Estee was the Coast Guard keeper 1978-80. He lived on the island with his wife, Kris, and their two young children, Nathaniel and Michelle. In an email in June 2011, Kris (Estee) Woodgate recalled life on the island:

It was such an adventure. We were quite young, early 20s, and from Wisconsin so we had never seen such a beautiful place ever. We were the ones who put in the new wooden walkway and cleaned up after the storm of 1978. The island was quite a mess. We had lots of company from Wisconsin; our relatives thought it was pretty awesome.

In 1990, Goat Island Light became the last lighthouse in Maine to be automated. Its Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern 300mm optic. Brad Culp, his wife Lisa and their two children Christian and Dakota were Maine's last traditional lighthouse family. Lisa Culp said of her eight-year old son Christian, "I think it's something he'll carry with him all his life."

Scott Dombrowski

For a time in the early 1990s during the presidency of George H. W. Bush, the island served as an air-sea command center complete with a radar beacon. Coast Guard personnel coordinated the surveillance of the harbor with the Secret Service.

In 1992, Goat Island was leased to the Kennebunkport Conservation Trust. In 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the lighthouse officially became the property of the trust, which since its founding in 1969 has protected much town land from development.

Scott Dombrowski, the island overseer for the trust, has spent some summers on the island with his wife, Karen, and their two sons, Eric and Gregory.

Dombrowski has been decorating Goat Island Light with an elaborate display of Christmas lights each holiday season for years.

In 1992, Goat Island was leased to the Kennebunkport Conservation Trust. In 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the lighthouse officially became the property of the trust, which since its founding in 1969 has protected much town land from development.

Scott Dombrowski, the island overseer for the trust, has spent some summers on the island with his wife, Karen, and their two sons, Eric and Gregory.

Dombrowski has been decorating Goat Island Light with an elaborate display of Christmas lights each holiday season for years.

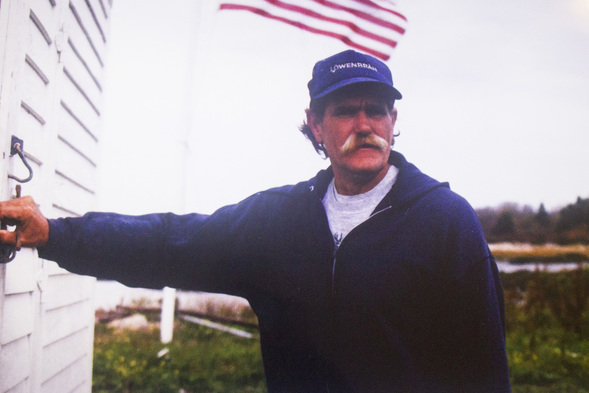

For about eight years, the caretaker on the island during most of the year was Dick Curtis.

Dick Curtis (Courtesy of Kennebunkport Conservation Trust)

Curtis died in a boating accident near the island in May 2002 at the age of 52 and is deeply missed by the members of the Kennebunkport Conservation Trust and local residents.

Goat Island Light remains an active aid to navigation. The lighthouse can be seen at a distance from the public wharf in Cape Porpoise. Visitors with private boats are welcome to the island and tour boats from Kennebunkport pass nearby.

The station's old fog bell was on display at the Kennebunkport Historical Society on North Street for many years.

Goat Island Light remains an active aid to navigation. The lighthouse can be seen at a distance from the public wharf in Cape Porpoise. Visitors with private boats are welcome to the island and tour boats from Kennebunkport pass nearby.

The station's old fog bell was on display at the Kennebunkport Historical Society on North Street for many years.

In the video above, caretaker Scott Dombrowski, speaks about the apparent presence on the island of his friend Dick Curtis, who died in 2002.

In July 2009, the Kennebunkport Conservation Trust announced plans to restore the station to the 1950s period.

Inside the tower

Work began in the spring of 2011 to rebuild the station's fog bell tower and the covered walkway as part of a $380,000 restoration project. The project was completed in the fall of 2011. The station's fog bell, long on display at the Kennebunkport Historical Society, was returned to the island and now hangs on the side of the tower.

For more information about the preservation of Goat Island Light, contact: Kennebunkport Conservation Trust.

For more information about the preservation of Goat Island Light, contact: Kennebunkport Conservation Trust.

|

Marty Cain, Coast Guard lighthouse keeper at Goat Island 1975-78, recalls life on the island. (Recorded Oct. 12, 2011)

|

Marty Cain Jr. recalls what happened on Goat Island during the Blizzard of 1978. (Recorded Oct. 12, 2011)

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Lord (1834-1841); Thatcher Hutchins (1841-1846); George Fletcher (1846-1850); Samuel Grant (1850-1858); George Averill (1858-1862); Joseph Huff (1862-1866); Stephen Illsley (1866-1873); Brad Emerson (1873-1878); John Emerson (1878-1887); Leander White (1887-1888); George Wakefield (1888-1921); Leo Allen (1921-1926); James M. Anderson (1926-1939); Justin Foss, Sr. (1939-1942); Austin Lamont Sinnett (c. 1940s?); Joseph Bakken (Coast Guard, 1946-1950); Robert McWilliams (Coast Guard, c. 1950-1953); Bruce Jordan (Coast Guard, 1953-?); Lavaughn (or Lavon) Bryant (Coast Guard, c. 1957), N3 John P. Reidy (relief keeper 1966-1967); Robert L. Haley (Coast Guard, 1968-1970); Charles Howard Worrell (Coast Guard, 1970-1972); Mark Brooke (Coast Guard, c. 1972-1975); Martin Cain (Coast Guard, 1975-1978); Mark Estey (Coast Guard, 1978-1980), Larry L. Toler (Coast Guard, 1981-1983), Bradley Culp (Coast Guard, 1985-1990).

John Lord (1834-1841); Thatcher Hutchins (1841-1846); George Fletcher (1846-1850); Samuel Grant (1850-1858); George Averill (1858-1862); Joseph Huff (1862-1866); Stephen Illsley (1866-1873); Brad Emerson (1873-1878); John Emerson (1878-1887); Leander White (1887-1888); George Wakefield (1888-1921); Leo Allen (1921-1926); James M. Anderson (1926-1939); Justin Foss, Sr. (1939-1942); Austin Lamont Sinnett (c. 1940s?); Joseph Bakken (Coast Guard, 1946-1950); Robert McWilliams (Coast Guard, c. 1950-1953); Bruce Jordan (Coast Guard, 1953-?); Lavaughn (or Lavon) Bryant (Coast Guard, c. 1957), N3 John P. Reidy (relief keeper 1966-1967); Robert L. Haley (Coast Guard, 1968-1970); Charles Howard Worrell (Coast Guard, 1970-1972); Mark Brooke (Coast Guard, c. 1972-1975); Martin Cain (Coast Guard, 1975-1978); Mark Estey (Coast Guard, 1978-1980), Larry L. Toler (Coast Guard, 1981-1983), Bradley Culp (Coast Guard, 1985-1990).

More Information About Yachts and Yachts for Sale: Yachts in Art Collections / Science of Yachts / Princess Yachts for Sale