History of Bird Island Lighthouse, Marion, Massachusetts

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Stark little Bird Island—less than two acres—is just a few hundred yards off Butler’s Point near the entrance to Marion's Sippican Harbor, on the west side of Buzzards Bay. The name “Sippican,” the local Indians’ word for “the long river” or “land of many waters,” according to different sources, once applied to a wide area.

WIth heavy maritime traffic in the area, including whaling ships and vessels engaged in the salt industry, Bird Island—about 1.5 acres in size—was an ideal place to establish a lighthouse that would serve to guide mariners into Sippican Harbor and points north.

Congress appropriated $11,500 on March 3, 1819, for three separate aids to navigation, including a lighthouse on Bird Island. The island was purchased by the government from George Blankinship for $200.

Congress appropriated $11,500 on March 3, 1819, for three separate aids to navigation, including a lighthouse on Bird Island. The island was purchased by the government from George Blankinship for $200.

Henry A. S. Dearborn, customs collector for the port of Boston and local lighthouse superintendent, contracted Bela Pratt of Weymouth, Massachusetts, to build the tower and other buildings at a cost of $4,040.

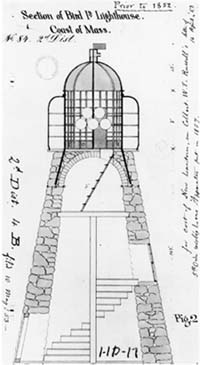

A 25-foot-tall conical rubblestone tower was constructed, surmounted by a 12-foot tall iron lantern. The accompanying stone dwelling was 20 by 34 feet, and a covered walkway connected the house and tower.

William S. Moore, a veteran of the War of 1812, was appointed as the first keeper, and the light went into operation on September 1, 1819.

A severe storm struck the area at the end of December 1819, devastating the new light station. Moore, who lost his boat and a large supply of wood, described the damage in a letter to Dearborn:

A very violent gale . . . has swept away every thing moveable from the island; and among other things my boat. . . . I was under the necessity of removing with my family into the light house, as the seas breaking against the dwelling house, threatened to fill the low part. . . . In the course of being at sea, I have experienced much severe weather, particularly the tornadoes of Africa, and other tropical climates, and they hardly exceed the violence of this gale for a short time.

Letters from Moore to Dearborn indicate that the keeper conducted experiments with the heating of whale oil to keep it from freezing in the winter months. He also worked on the development of “air boxes” to be stored on boats to help prevent sinking. Moore told Dearborn that he wanted to remain at Bird Island so he could pursue his various experiments. He explained, “. . . as the keeping of a lighthouse is calculated to afford me more leisure than almost any other employment, I shall give it up with great regret.”

William S. Moore, a veteran of the War of 1812, was appointed as the first keeper, and the light went into operation on September 1, 1819.

A severe storm struck the area at the end of December 1819, devastating the new light station. Moore, who lost his boat and a large supply of wood, described the damage in a letter to Dearborn:

A very violent gale . . . has swept away every thing moveable from the island; and among other things my boat. . . . I was under the necessity of removing with my family into the light house, as the seas breaking against the dwelling house, threatened to fill the low part. . . . In the course of being at sea, I have experienced much severe weather, particularly the tornadoes of Africa, and other tropical climates, and they hardly exceed the violence of this gale for a short time.

Letters from Moore to Dearborn indicate that the keeper conducted experiments with the heating of whale oil to keep it from freezing in the winter months. He also worked on the development of “air boxes” to be stored on boats to help prevent sinking. Moore told Dearborn that he wanted to remain at Bird Island so he could pursue his various experiments. He explained, “. . . as the keeping of a lighthouse is calculated to afford me more leisure than almost any other employment, I shall give it up with great regret.”

Persistent local legend claims that Moore was a pirate who was banished to Bird Island as punishment. Some versions of the story claim—preposterously—that he was left without a boat, with supplies delivered periodically. Since his boat is mentioned frequently in correspondence, this is clearly untrue. In any case, properly functioning lighthouses were vital to safe navigation, and the authorities strove to hire responsible and reliable men, not accused pirates.

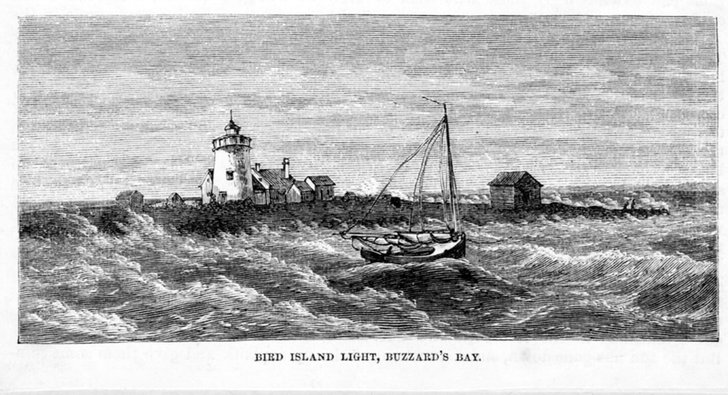

Bird Island Light circa 1859, with its original birdcage-style lantern (U.S. Coast Guard)

Some accounts claim that Moore murdered his wife—described as a “Boston society girl”—at the lighthouse and disappeared soon after. A rifle was purportedly found in a secret hiding place, along with a bag of tobacco, when the original keeper's house was torn down in 1889. The gun was believed by some to be the murder weapon. Others have claimed that Moore prevented his ailing wife from seeking medical attention on the mainland, and that she died as a result.

Although she is supposedly buried on the island, there is no sign of the grave of Moore’s wife today. With the gun, a note was found, signed by Moore. The note eventually came into the possession of Marion’s longtime town historian H. Edmund Tripp. It read:

This bag contains tobacco, found among the clothes of my wife after her decease. It was furnished by certain individuals in and about Sippican. May the curses of the High Heaven rest upon the heads of those who destroyed the peace of my family and the health and happiness of a wife whom I Dearly Loved.

Another far-fetched part of the lore surrounding William Moore is that he disappeared, never to be seen again, shortly after his wife’s death was discovered. In reality, records clearly show that Moore was assigned to the new Billingsgate Lighthouse near Wellfleet in 1822. It isn’t clear if he was able to continue his experiments there.

Although she is supposedly buried on the island, there is no sign of the grave of Moore’s wife today. With the gun, a note was found, signed by Moore. The note eventually came into the possession of Marion’s longtime town historian H. Edmund Tripp. It read:

This bag contains tobacco, found among the clothes of my wife after her decease. It was furnished by certain individuals in and about Sippican. May the curses of the High Heaven rest upon the heads of those who destroyed the peace of my family and the health and happiness of a wife whom I Dearly Loved.

Another far-fetched part of the lore surrounding William Moore is that he disappeared, never to be seen again, shortly after his wife’s death was discovered. In reality, records clearly show that Moore was assigned to the new Billingsgate Lighthouse near Wellfleet in 1822. It isn’t clear if he was able to continue his experiments there.

The truth about Moore will probably never be completely separated from the fantastic legends concerning his life. But his wife did die on the island, and there are those who say it has been haunted or cursed ever since. According to a newspaper article in the Standard Times, legend has it that some later keepers were frightened by the “ghost of a hunched-over old woman, rapping at the door during the night.”

John Clark was keeper from 1834 to 1849 and again from 1853 to 1861. In 1837, Clark warned that the seas were washing away the shoreline and could potentially split the island in two if not checked. He also complained of a bad whale oil supply that was “as thick as porage [sic].”

Bird Island Light was one of the few lighthouses of the early 1800s to have a revolving optic. Lieutenant Edward W. Carpender, in an important 1838 survey, questioned the necessity of a revolving light. He pointed out that there was no chance of this light being mistaken for another, since it was “aloof from all other lights.”

Bird Island Light was one of the few lighthouses of the early 1800s to have a revolving optic. Lieutenant Edward W. Carpender, in an important 1838 survey, questioned the necessity of a revolving light. He pointed out that there was no chance of this light being mistaken for another, since it was “aloof from all other lights.”

Carpender recommended that it be changed from a flashing white light to a fixed red light, and that the number of lamps be reduced from ten to six. This would, said Carpender, save taxpayers $143.50 yearly. The recommendations went unheeded.

Engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited Bird Island during his survey of 1842, and Clark provided him with this gloomy statement:

I was appointed keeper of this light in 1834, upon a salary of $400. . . The tower is in a bad state, very leaky, and wood work all more or less rotted. The lantern . . . is crowded exceedingly, and leaks badly at all the angles; the glass is continually broken by the rust; the lantern sweats very much, and makes ice upon the glass in winter half an inch thick. The whole light-house is in a bad state, and I think was not built in a faithful and workmanlike manner.

Clark also complained that he had to bring his drinking water from the mainland, as there was no source of fresh water on the island.

An authorization of $1,000 in 1843 paid for a new 600-foot stone seawall, a 25-foot extension to the wharf, the construction of a cistern for the water supply, the reshingling of the dwelling roof, and the painting of the buildings. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed in 1856. The 1863 annual report of the Lighthouse Board reported that a new lantern had been installed on the tower.

In November 1866, during Marshall V. Simmons’s stint as keeper (1861-69), a severe storm swept the island, flooding the cellar and the well, damaging the seawall and carrying away part of the enclosure fence. Repairs were swiftly completed.

Simmons was still the keeper on September 8, 1869, when a storm of “unprecedented severity” caused widespread destruction in New England. The seas covered Bird Island completely during the height of the storm, demolishing 280 feet of sea wall. The waves also destroyed a barn and carried away other outbuildings and fences. The official report stated that the lighthouse station was reduced “from a condition of perfect order to a perfect wreck.”

The keeper's dwelling was reported to be in a dilapidated condition in 1888. The annual report of the Lighthouse Board stated that the house was beyond repair:

It would be better economy, better for the comfort of the keeper, and for the efficiency of the public service that a new dwelling be built at the earliest day practicable.

The 1889 annual report contained the following misleading entry on Bird Island: “Measures are in progress for rebuilding the dwelling and tower surmounting it.” The house was clearly rebuilt at this time, but the tower at Bird Island had never surmounted the dwelling. This statement by the Lighthouse Board seems to account for the common assertion that the tower was rebuilt in 1889. There were a number of so-called “Cape Cod” style lighthouses with towers mounted on top of the keeper's dwellings in the nineteenth century, and someone may have confused Bird Island Lighthouse with another. The present tower clearly survives from 1819.

The station had an assistant keeper for a few years in the 1860s and 1870s. Charles A. Clark filled that role for a brief period before he became the principal keeper in 1872, and he would remain in charge until 1891. Clark’s brother was once cleaning a gun on the island—presumably for the hunting of waterfowl—when he accidentally shot himself. He was quickly transported by boat to a doctor in Marion and narrowly escaped death.

Peter Murray became keeper in 1891. In 1980, Murray's daughter, 91-year-old Frances Murray Rathbeg, recalled the family's life on the island, which she called a "sad place." The harsh winters, said Rathbeg, were especially difficult. During one winter, Keeper Murray's 11-month-old son, Gerald, became ill with pneumonia. "We had no way to get off the island," Rathbeg said. "The baby coughed and screamed."

I was appointed keeper of this light in 1834, upon a salary of $400. . . The tower is in a bad state, very leaky, and wood work all more or less rotted. The lantern . . . is crowded exceedingly, and leaks badly at all the angles; the glass is continually broken by the rust; the lantern sweats very much, and makes ice upon the glass in winter half an inch thick. The whole light-house is in a bad state, and I think was not built in a faithful and workmanlike manner.

Clark also complained that he had to bring his drinking water from the mainland, as there was no source of fresh water on the island.

An authorization of $1,000 in 1843 paid for a new 600-foot stone seawall, a 25-foot extension to the wharf, the construction of a cistern for the water supply, the reshingling of the dwelling roof, and the painting of the buildings. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed in 1856. The 1863 annual report of the Lighthouse Board reported that a new lantern had been installed on the tower.

In November 1866, during Marshall V. Simmons’s stint as keeper (1861-69), a severe storm swept the island, flooding the cellar and the well, damaging the seawall and carrying away part of the enclosure fence. Repairs were swiftly completed.

Simmons was still the keeper on September 8, 1869, when a storm of “unprecedented severity” caused widespread destruction in New England. The seas covered Bird Island completely during the height of the storm, demolishing 280 feet of sea wall. The waves also destroyed a barn and carried away other outbuildings and fences. The official report stated that the lighthouse station was reduced “from a condition of perfect order to a perfect wreck.”

The keeper's dwelling was reported to be in a dilapidated condition in 1888. The annual report of the Lighthouse Board stated that the house was beyond repair:

It would be better economy, better for the comfort of the keeper, and for the efficiency of the public service that a new dwelling be built at the earliest day practicable.

The 1889 annual report contained the following misleading entry on Bird Island: “Measures are in progress for rebuilding the dwelling and tower surmounting it.” The house was clearly rebuilt at this time, but the tower at Bird Island had never surmounted the dwelling. This statement by the Lighthouse Board seems to account for the common assertion that the tower was rebuilt in 1889. There were a number of so-called “Cape Cod” style lighthouses with towers mounted on top of the keeper's dwellings in the nineteenth century, and someone may have confused Bird Island Lighthouse with another. The present tower clearly survives from 1819.

The station had an assistant keeper for a few years in the 1860s and 1870s. Charles A. Clark filled that role for a brief period before he became the principal keeper in 1872, and he would remain in charge until 1891. Clark’s brother was once cleaning a gun on the island—presumably for the hunting of waterfowl—when he accidentally shot himself. He was quickly transported by boat to a doctor in Marion and narrowly escaped death.

Peter Murray became keeper in 1891. In 1980, Murray's daughter, 91-year-old Frances Murray Rathbeg, recalled the family's life on the island, which she called a "sad place." The harsh winters, said Rathbeg, were especially difficult. During one winter, Keeper Murray's 11-month-old son, Gerald, became ill with pneumonia. "We had no way to get off the island," Rathbeg said. "The baby coughed and screamed."

With no other way to signal for help, the desperate keeper extinguished the light to attract attention. Help eventually arrived, but too late; the baby had died. The Murrays buried their child on the mainland and never returned to Bird Island.

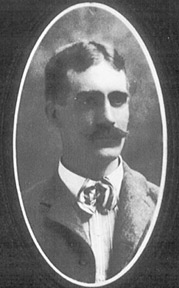

Zimri Robinson

As was often the case on island lighthouse stations, the families on Bird Island kept animals to augment their food supply. Keeper Zimri Tobias "Toby" Robinson brought a cow to the island while he was keeper. According to his brother's grandson, Keeper Robinson attached a rope to the cow and tied it to his skiff, then rowed to the island with the cow swimming behind. Robinson and his wife, Angie, also kept a flock of chickens and a substantial garden. Angie Robinson always had a chicken dinner ready for visiting lighthouse inspectors.

During a tremendous storm on the night of September 30, 1907, Keeper Robinson spotted a motor vessel in distress with two men aboard. Robinson went out in his boat and rescued the men, but they were not able to return to safety until the next morning, after hours of drifting in the gale.

During a tremendous storm on the night of September 30, 1907, Keeper Robinson spotted a motor vessel in distress with two men aboard. Robinson went out in his boat and rescued the men, but they were not able to return to safety until the next morning, after hours of drifting in the gale.

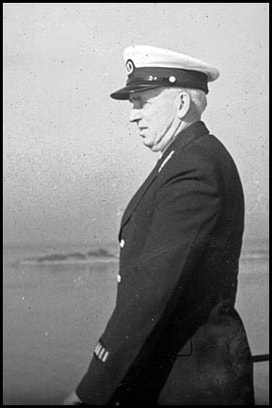

Wisconsin native George T. Gustavus, father of 10 children and a 16-year veteran of lighthouse keeping, was the next and—as it turned out—the last keeper. Gustavus made the pages of the Lighthouse Service Bulletin on May 1, 1930, for towing a motorboat to safety after it had become disabled near the island.

George Gustavus. Courtesy of Joan Kenworthy.

Gustavus and his family left Bird Island Light when it was taken out of service on June 15, 1933. The building of the Cape Cod Canal had led to more traffic in Buzzards Bay, but lighted buoys close to the main shipping channels eliminated the need for Bird Island Light.

The hurricane of September 21, 1938, caused widespread destruction all along the south coast of New England, and Marion was no exception. High tide in the evening of the hurricane was 14 feet above normal. The great storm swept away every building on Bird Island except the lighthouse tower.

Some local residents said they saw the station's enormous fog bell being swept off the island in the storm; others say it had been removed before the storm.

In March 1940, the government island sold the island at auction to George Harmon of Bar Harbor, Maine, for $654. Just a month later, the island was purchased by Augustus Fiske of Providence, Rhode Island. Apparently, not much was done with the property over the ensuing 25 years.

The hurricane of September 21, 1938, caused widespread destruction all along the south coast of New England, and Marion was no exception. High tide in the evening of the hurricane was 14 feet above normal. The great storm swept away every building on Bird Island except the lighthouse tower.

Some local residents said they saw the station's enormous fog bell being swept off the island in the storm; others say it had been removed before the storm.

In March 1940, the government island sold the island at auction to George Harmon of Bar Harbor, Maine, for $654. Just a month later, the island was purchased by Augustus Fiske of Providence, Rhode Island. Apparently, not much was done with the property over the ensuing 25 years.

In March 1940, the government island sold the island at auction to George Harmon of Bar Harbor, Maine, for $654. Just a month later, the island was purchased by Augustus Fiske of Providence, Rhode Island. Apparently, not much was done with the property over the ensuing 25 years. In early 1965, the Marion Conservation Commission announced that donations were being accepted toward the purchase of the island. A lighthouse-shaped thermometer was erected in front of the Sippican Shop in Marion to indicate the fundraising progress.

The town bought the island from Fiske’s heirs in May 1966 for $2,500.

It was announced in 1973 that $12,500 had been raised for the restoration of the lighthouse and to erect a fence, designed to protect the island’s nesting tern colony.

The lighthouse was relighted on July 9, 1976, as part of Marion’s celebration of the nation’s bicentennial, but the tower subsequently fell into further disrepair and the light was again extinguished.

Left: Bird Island Light before restoration. Photo by Patricia Evenson.

The lighthouse was relighted on July 9, 1976, as part of Marion’s celebration of the nation’s bicentennial, but the tower subsequently fell into further disrepair and the light was again extinguished.

Left: Bird Island Light before restoration. Photo by Patricia Evenson.

In 1994, a new effort was mounted when the Bird Island Preservation Society was formed by Charles J. Bradley, a local shellfish officer.

In 1996, the society hired International Chimney Corp. of Buffalo, New York, to do restoration work. The company had gained fame in lighthouse circles after their successful moves of Block Island Southeast Light in Rhode Island, and Highland and Nauset lights in Massachusetts.

Jim Scott, a foreman for International Chimney, noted that the lighthouse was very solidly built and would be around for a long time to come. The International Chimney crew arrived on the island in October 1996 and began with the sandblasting and repointing of the exterior. After completing much of the project that fall, the workers returned in the following spring to finish the job.

Right: Rubble from the foundation of the keeper's house, seen from the top of the tower in April 2004. The square structure at the left was a cistern.

Jim Scott, a foreman for International Chimney, noted that the lighthouse was very solidly built and would be around for a long time to come. The International Chimney crew arrived on the island in October 1996 and began with the sandblasting and repointing of the exterior. After completing much of the project that fall, the workers returned in the following spring to finish the job.

Right: Rubble from the foundation of the keeper's house, seen from the top of the tower in April 2004. The square structure at the left was a cistern.

In June 1997, the Marion Board of Selectmen asked Charles Bradley if his group had the funds for a new optic to be installed in the tower. Bradley replied that they didn't, so the selectmen decided to provide $3,000 for a new solar-powered flashing light and its installation.

At 9:00 p.m. on July 4, 1997, with 3,000 people gathered onshore, Bird Island Light was relighted as a private aid to navigation.

Right: Marion Harbormaster and Bird Island "Keeper" Charles Bradley in the lantern room on April 29, 2004.

In February 2008, Charles Bradley stepped down as chairman of the Bird Island Lighthouse Preservation Society. Custody of Bird Island was transferred to the Marion Marine Department in 1998.

The nesting population of roseate terns—an endangered species—on the island is around 1100 pairs. It’s the largest breeding colony of the species in North America. In fact, it comprises about 30% of the North American population of roseate terns. In 2016-17, the island underwent much work to rebuild the seawall along with other erosion control measures. Click here for more information.

Bird Island Light can be seen distantly from shore but is best viewed by private boat. Donations for the preservation of the lighthouse may be sent to the Marion Marine Gift Fund, 2 Spring Street, Marion, MA 02738.

Right: Marion Harbormaster and Bird Island "Keeper" Charles Bradley in the lantern room on April 29, 2004.

In February 2008, Charles Bradley stepped down as chairman of the Bird Island Lighthouse Preservation Society. Custody of Bird Island was transferred to the Marion Marine Department in 1998.

The nesting population of roseate terns—an endangered species—on the island is around 1100 pairs. It’s the largest breeding colony of the species in North America. In fact, it comprises about 30% of the North American population of roseate terns. In 2016-17, the island underwent much work to rebuild the seawall along with other erosion control measures. Click here for more information.

Bird Island Light can be seen distantly from shore but is best viewed by private boat. Donations for the preservation of the lighthouse may be sent to the Marion Marine Gift Fund, 2 Spring Street, Marion, MA 02738.

Above: In this video, New England Boating's Tom Richardson offers a rare look at this one-acre island in Buzzards Bay.

Keepers (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.):

William S. Moore (1819-1834); John Clark (1834-1849 and 1853-1861); James Delano (1849-1853); Marshall V. Simmons (1861-1867); W. A. Simmons (assistant, 1867-1868; principal keeper 1869-1872); A. B. Bowman (assistant, 1868-1869); Russell G. Gray (assistant 1870-1871); Charles A. Clark (assistant 1871-1872; principal keeper 1872-1891); Jabez Jenney (assistant, 1872); Peter Murray (1891-1895); Zimri Tobias ("Toby") Robinson (1895-1912); C. W. Jordan (1912); Elliott Hadley, Jr. (1912-1917); H. H. Davis (1917-1919); Maurice A. Babcock (1919-1926); George T. Gustavus (1926-1933).

William S. Moore (1819-1834); John Clark (1834-1849 and 1853-1861); James Delano (1849-1853); Marshall V. Simmons (1861-1867); W. A. Simmons (assistant, 1867-1868; principal keeper 1869-1872); A. B. Bowman (assistant, 1868-1869); Russell G. Gray (assistant 1870-1871); Charles A. Clark (assistant 1871-1872; principal keeper 1872-1891); Jabez Jenney (assistant, 1872); Peter Murray (1891-1895); Zimri Tobias ("Toby") Robinson (1895-1912); C. W. Jordan (1912); Elliott Hadley, Jr. (1912-1917); H. H. Davis (1917-1919); Maurice A. Babcock (1919-1926); George T. Gustavus (1926-1933).