History of Rose Island Lighthouse, Newport, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Rose Island, about a mile offshore from Newport, has a commanding position in Narragansett Bay's East Passage, with a clear view to the south all the way to Block Island.

The island -- once more than 25 acres in size -- today encompasses only about 18 acres. It would appear to any summer visitor that the island's present name comes from the presence of abundant Rosa rugosa bushes, but that's not the case. Some think it was named for the shape of the island, with the long point being the stem.

A fort was partially built on Rose Island beginning in 1798. Fort Hamilton was never finished, armed or garrisoned, but some of the structures were used to store explosives in both World War I and II.

The waters around Newport were thick with passenger steamers, fishing boats, and freighters in the mid-nineteenth century. The southwest corner of Rose Island was an ideal place for a light to help guide navigators passing through the East Passage of the bay and those approaching Newport, as well as to warn of dangerous shoals north of Newport Harbor. On July 20, 1868, Congress appropriated $7,500 for a lighthouse.

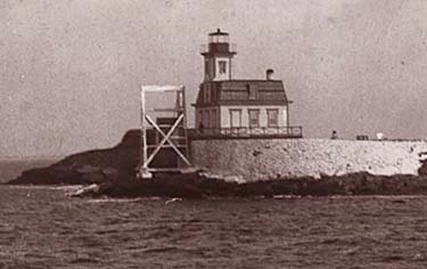

The site chosen was a surviving bastion of eighteenth-century Fort Hamilton. The architecture of the lighthouse is similar to several built in the period, including Pomham Rocks Light on the Providence River. An octagonal lighthouse tower rises from the west side of the mansard roof atop the handsome one-and-one-half-story wooden keeper's dwelling. The lighthouse is 35 feet tall, with the focal plane 48 feet above the water.

A fort was partially built on Rose Island beginning in 1798. Fort Hamilton was never finished, armed or garrisoned, but some of the structures were used to store explosives in both World War I and II.

The waters around Newport were thick with passenger steamers, fishing boats, and freighters in the mid-nineteenth century. The southwest corner of Rose Island was an ideal place for a light to help guide navigators passing through the East Passage of the bay and those approaching Newport, as well as to warn of dangerous shoals north of Newport Harbor. On July 20, 1868, Congress appropriated $7,500 for a lighthouse.

The site chosen was a surviving bastion of eighteenth-century Fort Hamilton. The architecture of the lighthouse is similar to several built in the period, including Pomham Rocks Light on the Providence River. An octagonal lighthouse tower rises from the west side of the mansard roof atop the handsome one-and-one-half-story wooden keeper's dwelling. The lighthouse is 35 feet tall, with the focal plane 48 feet above the water.

The lighthouse went into service on January 20, 1870, with a sixth-order Fresnel lens exhibiting a fixed red light. A fog bell tower and striking apparatus were added to the station in 1885, with the bell striking a double blow every 15 seconds. The first keeper was John Bailey Cozzens.

U.S. Coast Guard

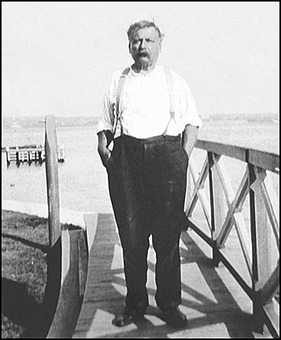

Charles Slocum Curtis became keeper in 1887, and his 31-year stay would be the longest in Rose Island's history. Curtis saw plenty of change in his decades at the station, including the replacement of the 1885 fog bell by a new horn. With the added duties of running the equipment associated with the foghorn, the station was assigned an assistant keeper beginning in late 1912.

Every day near sunset, Keeper Curtis would aim his ears toward Newport's Fort Adams and listen for the "sundown gun." After hearing the cannon blast, he'd lower the Stars and Stripes, and then go up in the tower to "light up" for the evening. He rigged a mirror outside on a pole near a living room window, making it easier to check on the light during the evening. After going to bed, Curtis would rise to check the light again at midnight. During the day, Curtis kept busy tending the family's vegetable garden, or boating to Newport for supplies.

Every day near sunset, Keeper Curtis would aim his ears toward Newport's Fort Adams and listen for the "sundown gun." After hearing the cannon blast, he'd lower the Stars and Stripes, and then go up in the tower to "light up" for the evening. He rigged a mirror outside on a pole near a living room window, making it easier to check on the light during the evening. After going to bed, Curtis would rise to check the light again at midnight. During the day, Curtis kept busy tending the family's vegetable garden, or boating to Newport for supplies.

While the fog bell was still in use, Keeper Curtis and his wife, Christina, had to go ashore one day. They left their daughter, Mabel, alone on the island. Thick fog suddenly rolled in.

Charles Curtis. (Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation)

Young Mabel couldn't get the fog bell mechanism started, so she grabbed a hammer and manually rang the bell, approximating its official time sequence for several hours until her parents returned. Mabel often rowed herself to Newport to attend school. If the seas were rough or it was too foggy to return the same day, she would sometimes stay overnight with friends living on Washington Street. Mabel also went "crabbing" around the island and would sell the crabs to make a little money.

There were other ways for an industrious young person to make money on Rose Island. Mabel's father paid her fifty cents to clean the brass in the lighthouse, and she earned eight dollars for digging the family's garden.

We know a great deal about the Curtis family's years on the island, thanks largely to Charles's grandson (Mabel's son), Wanton Chase. His vivid memories played a vital role in the recent restoration of the lighthouse as a living museum. Wanton's tales of lighthouse life were put down on paper with the help of a friend, Natalie Nicholson, and published by the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation in 2001 as a booklet called Boyhood Life at Rose Island.

There were other ways for an industrious young person to make money on Rose Island. Mabel's father paid her fifty cents to clean the brass in the lighthouse, and she earned eight dollars for digging the family's garden.

We know a great deal about the Curtis family's years on the island, thanks largely to Charles's grandson (Mabel's son), Wanton Chase. His vivid memories played a vital role in the recent restoration of the lighthouse as a living museum. Wanton's tales of lighthouse life were put down on paper with the help of a friend, Natalie Nicholson, and published by the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation in 2001 as a booklet called Boyhood Life at Rose Island.

An assistant keeper was assigned to the station around 1912. In February 1917, Assistant Keeper Julius Johanson (or Johansen) drowned when his boat capsized as he traveling to shore for provisions.

Jesse Orton was keeper from 1921 to 1936. His grandson, Paul Stedman, often visited in the summer and helped with the lighthouse duties.

Stedman, who lived in Florida and visited the lighthouse every summer, remembered one time when his grandfather and his assistant saw a lighthouse tender approaching for a surprise inspection. The assistant keeper, Charlie Eldredge, realized that he had forgotten to blacken the coal stove, which had rusted. A rusty stove would be a black mark in the inspection. As the tender approached the men made a fire in the stove and put pots full of water on the burners. The men told the inspector they were preparing a large meal for some expected guests, and the rust wasn't noticed.

Left: Paul Stedman and his grandfather, Keeper Jesse Orton. Courtesy of Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation.

George S. Bell came to Rose Island as a Lighthouse Service keeper in 1936. When the Coast Guard took over operation of lighthouses three years later, Bell enlisted in that branch of the military. He remained the officer in charge until 1952.

Bell and his daughter, Charlotte, were alone at the lighthouse when the devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938, struck the area. As the great storm pounded the bay, tremendous waves smashed against the keeper's dwelling at Rose Island. Bell and his daughter literally had to bail out the house at the height of the storm, throwing buckets full of seawater out of the north-facing windows. When the wind shifted to the other direction, they dumped the water out of the windows that faced south.

Left: Paul Stedman and his grandfather, Keeper Jesse Orton. Courtesy of Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation.

George S. Bell came to Rose Island as a Lighthouse Service keeper in 1936. When the Coast Guard took over operation of lighthouses three years later, Bell enlisted in that branch of the military. He remained the officer in charge until 1952.

Bell and his daughter, Charlotte, were alone at the lighthouse when the devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938, struck the area. As the great storm pounded the bay, tremendous waves smashed against the keeper's dwelling at Rose Island. Bell and his daughter literally had to bail out the house at the height of the storm, throwing buckets full of seawater out of the north-facing windows. When the wind shifted to the other direction, they dumped the water out of the windows that faced south.

The majority of the island, formerly used for military purposes, was declared surplus after World War II. It was sold in 1969 to a group of local businessmen who, in the 1980s, proposed to build a 125-unit condominium complex and a 200-slip marina.

A room in the lighthouse

The light lost its importance as a navigational aid with the construction of the Newport Bridge in 1969. After it was decommissioned by the Coast Guard in 1971, the lighthouse was leased for a time to the University of Rhode Island for use as a marine research facility. Vandalism prevented the university from establishing a permanent station there.

Finally, in the early 1980s, the badly vandalized lighthouse was declared surplus. A group of dedicated preservationists founded the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation to protect the historic structure.

In 1985, the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation took over the lighthouse property and began the process of restoring the building inside and out. The lighthouse has been restored to the 1912-1915 period, with a coal stove in the kitchen and a working Victrola with a large supply of 78 rpm records in the library.

In 1992, the Rose Island Foundation opened the lighthouse to the public, and on August 7, 1993 Rose Island Lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation. Christopher Owens, caretaker of the lighthouse for a time, later remembered his impressions of the relighting:

Flipping the switch and watching that beacon light for the first time in 20 years was special, yet for me the magic moment followed seconds later. All was quiet for a moment, then I heard one small horn and another and yet another until we were surrounded by sounding horns from all around the bay. Boats, cars... horns of every sort sounded.

Finally, in the early 1980s, the badly vandalized lighthouse was declared surplus. A group of dedicated preservationists founded the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation to protect the historic structure.

In 1985, the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation took over the lighthouse property and began the process of restoring the building inside and out. The lighthouse has been restored to the 1912-1915 period, with a coal stove in the kitchen and a working Victrola with a large supply of 78 rpm records in the library.

In 1992, the Rose Island Foundation opened the lighthouse to the public, and on August 7, 1993 Rose Island Lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation. Christopher Owens, caretaker of the lighthouse for a time, later remembered his impressions of the relighting:

Flipping the switch and watching that beacon light for the first time in 20 years was special, yet for me the magic moment followed seconds later. All was quiet for a moment, then I heard one small horn and another and yet another until we were surrounded by sounding horns from all around the bay. Boats, cars... horns of every sort sounded.

You can stay overnight at Rose Island for a taste of Lighthouse Service life.

A view from the top, looking toward the Newport Bridge

At this "living museum," guests are responsible for cleaning up after themselves, changing the linens, and having the rooms back in order before the museum opens at 10 a.m. the next morning. You might call it "light housekeeping."

You can also stay in the upstairs apartment for a week, acting as "keeper" during your stay. Each day the keeper raises the flag, records the weather, electric and water data, and performs other maintenance chores.

Electricity is produced mainly by a wind turbine and stored in solar batteries. Rain water is collected in a basement cistern and treated with chlorine, with additional bottled spring water for drinking. The accommodations aren't deluxe, but guests love the experience.

The Newport and Jamestown ferry makes daily loops in summer between Jamestown and Newport and will stop at Rose Island on request. Part of the year access is limited for the protection of nesting birds on the the north and east parts of the island. Rose Island Lighthouse is also open for tours to schools and other groups.

In 2013-14, much more restoration was completed, including the installation of a replica sixth-order Fresnel lens. This island lighthouse is one of New England's happiest restoration stories.

For more information: Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation

You can also stay in the upstairs apartment for a week, acting as "keeper" during your stay. Each day the keeper raises the flag, records the weather, electric and water data, and performs other maintenance chores.

Electricity is produced mainly by a wind turbine and stored in solar batteries. Rain water is collected in a basement cistern and treated with chlorine, with additional bottled spring water for drinking. The accommodations aren't deluxe, but guests love the experience.

The Newport and Jamestown ferry makes daily loops in summer between Jamestown and Newport and will stop at Rose Island on request. Part of the year access is limited for the protection of nesting birds on the the north and east parts of the island. Rose Island Lighthouse is also open for tours to schools and other groups.

In 2013-14, much more restoration was completed, including the installation of a replica sixth-order Fresnel lens. This island lighthouse is one of New England's happiest restoration stories.

For more information: Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation

|

The song "Flashing in the Dark" by Neptune's Car was inspired by Rose Island Lighthouse. This video was shot on the island in 2012.

|

David McCurdy, executive director of the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation describes the restoration work completed in 2013-14. Shot on May 2, 2014.

|

Special thanks to Charlotte Johnson for her assistance with this history.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Bailey Cozzens (1869-1872); George C. Williams (1872-1879); Gustave A. Clark (1879-1887); Charles S. Curtis (1887-1918); Thomas Pickup (1919-1921); Jesse Orton (1921-1936); Charles Eldridge (1936-1941)

Assistants: Julius Johansen (1912-1917); Delaney E. Roode (1917-1919); B. Arthur Bessett (1920-1921); E. W. Newton (1921-1926); Charles Eldridge (1926-1936); George S. Bell (1936-1952)

John Bailey Cozzens (1869-1872); George C. Williams (1872-1879); Gustave A. Clark (1879-1887); Charles S. Curtis (1887-1918); Thomas Pickup (1919-1921); Jesse Orton (1921-1936); Charles Eldridge (1936-1941)

Assistants: Julius Johansen (1912-1917); Delaney E. Roode (1917-1919); B. Arthur Bessett (1920-1921); E. W. Newton (1921-1926); Charles Eldridge (1926-1936); George S. Bell (1936-1952)