History of Hog Island Shoal Lighthouse, Portsmouth, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Hog Island, some 200 acres in area, sits in Narragansett Bay right in the middle of the approach to Bristol Harbor, just west of the entrance to Mount Hope Bay.

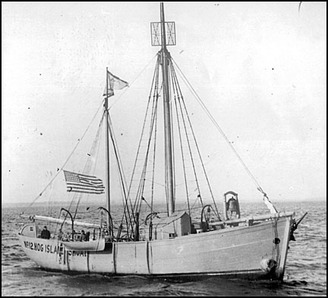

The Hog Island Shoal Lightship (LV-12). U.S. Coast Guard.

The island itself, despite past efforts to promote it as a resort (one marketing effort dubbed the summer colony "Paradise Island Park," certainly a more marketable name than Hog Island), remains sparsely populated today with about 120 homes.

Treacherous shoals extend to the south of the island, and a buoy was placed to mark the area in 1838. In 1866, the Old Colony Steamboat Company established a small light boat south of the island in support of their own vessels that ran between Newport and Fall River. The light on this boat was too dim to be of much use, so the Eel Grass Shoal Lightship, LV 12, was relocated from Fisher's Island Sound to Hog Island Shoal in 1886.

By 1889, the lightship, which had been built in 1846, was in poor condition, and it was decided that a lighthouse would be built to replace it. Congress approved $35,000 for the lighthouse on March 3, 1899. The site was surveyed and a suitable location was found, about 600 yards southeast of Hog Island. The lighthouse is about 250 yards north of the location of the earlier lightship.

The contractor hired to build the lighthouse was Toomey Brothers of Guilford, Connecticut. Just a short time earlier, the company had built the superstructure of the Plum Beach Lighthouse in the west passage of Narragansett Bay. The design of the new lighthouse for Hog Island Shoal was very similar to that of Plum Beach Light—a cylindrical cast-iron combined lighthouse/dwelling atop a concrete-filled cast-iron caisson. The style became a standard for offshore lighthouses built from the 1870s into the early 1900s; because of their shape, they are often referred to as “spark plug” or “coffeepot” towers.

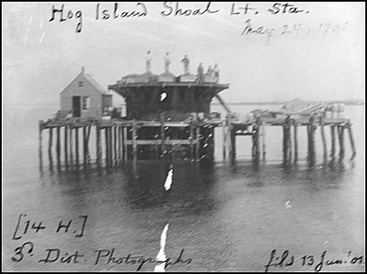

A temporary wharf was built on the south side of Hog Island to be used as a staging area for the construction project. By June 30, 1901, the foundation cylinder—25 feet in diameter—was erected on the chosen site and filled with concrete, with space left for a basement storage area. The cylinder was sunk 8 1/2 feet into the bottom of the shoal.

Treacherous shoals extend to the south of the island, and a buoy was placed to mark the area in 1838. In 1866, the Old Colony Steamboat Company established a small light boat south of the island in support of their own vessels that ran between Newport and Fall River. The light on this boat was too dim to be of much use, so the Eel Grass Shoal Lightship, LV 12, was relocated from Fisher's Island Sound to Hog Island Shoal in 1886.

By 1889, the lightship, which had been built in 1846, was in poor condition, and it was decided that a lighthouse would be built to replace it. Congress approved $35,000 for the lighthouse on March 3, 1899. The site was surveyed and a suitable location was found, about 600 yards southeast of Hog Island. The lighthouse is about 250 yards north of the location of the earlier lightship.

The contractor hired to build the lighthouse was Toomey Brothers of Guilford, Connecticut. Just a short time earlier, the company had built the superstructure of the Plum Beach Lighthouse in the west passage of Narragansett Bay. The design of the new lighthouse for Hog Island Shoal was very similar to that of Plum Beach Light—a cylindrical cast-iron combined lighthouse/dwelling atop a concrete-filled cast-iron caisson. The style became a standard for offshore lighthouses built from the 1870s into the early 1900s; because of their shape, they are often referred to as “spark plug” or “coffeepot” towers.

A temporary wharf was built on the south side of Hog Island to be used as a staging area for the construction project. By June 30, 1901, the foundation cylinder—25 feet in diameter—was erected on the chosen site and filled with concrete, with space left for a basement storage area. The cylinder was sunk 8 1/2 feet into the bottom of the shoal.

The components of the superstructure were delivered beginning in July, and by August 31 the lighthouse was completed to the lantern level. It was reported that by September 12, workers had completed “the painting of the interior of the tower with two coats of red lead, whitewashing the brickwork of the cellar stairs, and coating the brick lining of the tower with hot oil.”

The construction of Hog Island Shoal Light.

U.S. Coast Guard.

For protection from drifting ice, 1,500 tons of riprap stone—huge pieces of granite—were piled around the caisson. There’s never been any sort of dock at the lighthouse; access has always been provided by a ladder leading to hatch that opens onto the main gallery deck.

By the end of September, the lantern was in place and a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed. The height of the tower is 60 feet from the water to the top of the lantern. Although the light was in operation by October 1901, the station didn’t become fully operational until April 5, 1902, after a fog signal and duplicate oil engines were put in. A fourth-order lens replaced the original lens on September 15, 1903, and the characteristic was changed from flashing to fixed white.

The first three levels above the basement—the living and working space for the keepers—are 20 feet in diameter. The diameter of the next level, the watchroom, is 11 feet. Three galleries—at the first, watchroom, and lantern levels—surround the tower. The cylindrical cast-iron lantern has diamond-shaped panes of glass, a distinguishing feature not found in most similar lighthouses.

The LV 12 remained in service until the lighthouse was in operation. One of the officers in charge of the vessel, Augustus Hall, committed suicide by jumping overboard in early February 1887. An inspector who boarded the vessel in the summer of 1901 found the keeper in a drunken state. The man was summarily dismissed from the service. After the lighthouse was completed, the dilapidated old lightship was sold at auction for $360.

For protection from drifting ice, 1,500 tons of riprap stone-huge pieces of granite-were piled around the caisson. There's never been any sort of dock at the lighthouse; access has always been provided by a ladder leading to hatch that opens onto the main gallery deck. The structure has five decks; the second and third decks were the living quarters for the keepers.

By the end of September, the lantern was in place and a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed. The height of the tower is 60 feet from the water to the top of the lantern. Although the light was in operation by October 1901, the station didn’t become fully operational until April 5, 1902, after a fog signal and duplicate oil engines were put in. A fourth-order lens replaced the original lens on September 15, 1903, and the characteristic was changed from flashing to fixed white.

The first three levels above the basement—the living and working space for the keepers—are 20 feet in diameter. The diameter of the next level, the watchroom, is 11 feet. Three galleries—at the first, watchroom, and lantern levels—surround the tower. The cylindrical cast-iron lantern has diamond-shaped panes of glass, a distinguishing feature not found in most similar lighthouses.

The LV 12 remained in service until the lighthouse was in operation. One of the officers in charge of the vessel, Augustus Hall, committed suicide by jumping overboard in early February 1887. An inspector who boarded the vessel in the summer of 1901 found the keeper in a drunken state. The man was summarily dismissed from the service. After the lighthouse was completed, the dilapidated old lightship was sold at auction for $360.

For protection from drifting ice, 1,500 tons of riprap stone-huge pieces of granite-were piled around the caisson. There's never been any sort of dock at the lighthouse; access has always been provided by a ladder leading to hatch that opens onto the main gallery deck. The structure has five decks; the second and third decks were the living quarters for the keepers.

Few stories seem to have been preserved about the keepers who lived here during the 63 years this lighthouse was staffed.

U.S. Coast Guard

A 1946 article tells us that the keepers at that time were Edward F. Duffy, a 30-year veteran of the Lighthouse Service and the Coast Guard, and Francis H. Peloquin, who had 21 years of service.

Earlier, in July 1935, Duffy had made the pages of the U.S. Lighthouse Service Bulletin when he and First Assistant Keeper Mahlon Burdge recovered the body of a man who had drowned after falling from his motorboat near the lighthouse.

The light was converted from kerosene to electricity in 1959 with the laying of a submarine cable. It was among the last lights in the nation to be electrified. Automation was completed in the spring of 1964 and the last Coast Guard keepers were removed.

Coast Guard crews have performed first aid on the aging lighthouse several times in recent years. In the fall of 1986, personnel from Aids to Navigation Team Bristol carried out an overhaul of the lighthouse. The caisson was sandblasted and repainted, the old access ladder was removed and reattached in a more secure manner, broken and missing handrails were replaced, and two old deteriorated boat davits were removed. Two other davits were left in place on the tower's north side.

Coast Guard personnel from Bristol currently check on the equipment at the lighthouse every three months, and access can be difficult and risky. The crew must hop from a boat onto the ladder, and then climb up to the deck. This is easier said than done, particularly when the seas are rough and you're loaded down with equipment.

In 2004, the lighthouse was made available to a new owner under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 (NHLPA). Officials of nearby Roger Williams University reportedly showed some interest in the structure but decided not to apply for ownership. There were no applicants within the allotted time period, meaning the lighthouse was auctioned to the highest bidder under the provisions of the NHLPA. In November 2006, it was officially announced that the lighthouse had been sold for $165,000 to Jon and Juli Chytka of South Dakota.

The lighthouse can be seen from many vantage points, including from the Mount Hope Bridge. The Prudence Island ferry from Bristol passes fairly close by.

Earlier, in July 1935, Duffy had made the pages of the U.S. Lighthouse Service Bulletin when he and First Assistant Keeper Mahlon Burdge recovered the body of a man who had drowned after falling from his motorboat near the lighthouse.

The light was converted from kerosene to electricity in 1959 with the laying of a submarine cable. It was among the last lights in the nation to be electrified. Automation was completed in the spring of 1964 and the last Coast Guard keepers were removed.

Coast Guard crews have performed first aid on the aging lighthouse several times in recent years. In the fall of 1986, personnel from Aids to Navigation Team Bristol carried out an overhaul of the lighthouse. The caisson was sandblasted and repainted, the old access ladder was removed and reattached in a more secure manner, broken and missing handrails were replaced, and two old deteriorated boat davits were removed. Two other davits were left in place on the tower's north side.

Coast Guard personnel from Bristol currently check on the equipment at the lighthouse every three months, and access can be difficult and risky. The crew must hop from a boat onto the ladder, and then climb up to the deck. This is easier said than done, particularly when the seas are rough and you're loaded down with equipment.

In 2004, the lighthouse was made available to a new owner under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 (NHLPA). Officials of nearby Roger Williams University reportedly showed some interest in the structure but decided not to apply for ownership. There were no applicants within the allotted time period, meaning the lighthouse was auctioned to the highest bidder under the provisions of the NHLPA. In November 2006, it was officially announced that the lighthouse had been sold for $165,000 to Jon and Juli Chytka of South Dakota.

The lighthouse can be seen from many vantage points, including from the Mount Hope Bridge. The Prudence Island ferry from Bristol passes fairly close by.

Below: Inside Hog Island Shoal Light in 2013. Photos by Nick Korstad, used by permission.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Lightship: Augustus Hall (lightship, 1886-1887), August Wohlstrom (assistant 1887, keeper 1887-1891), Eben A. Smith (assistant 1887), George S, Slocum (assistant 1887-?), Samuel Wright (1891-?)

Lighthouse: William H. Follett (first assistant, 1904-1905); Edward Duffy (c. 1921-1946), Patrick J. Brides (1st assistant, c. 1921), George F. Stone (2nd assistant, c. 1921), Mahlon Burdge (c. 1935), Francis H. Peloquin (c. 1940s)

Lightship: Augustus Hall (lightship, 1886-1887), August Wohlstrom (assistant 1887, keeper 1887-1891), Eben A. Smith (assistant 1887), George S, Slocum (assistant 1887-?), Samuel Wright (1891-?)

Lighthouse: William H. Follett (first assistant, 1904-1905); Edward Duffy (c. 1921-1946), Patrick J. Brides (1st assistant, c. 1921), George F. Stone (2nd assistant, c. 1921), Mahlon Burdge (c. 1935), Francis H. Peloquin (c. 1940s)