History of Marblehead Light, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Marblehead is a sailing mecca and a picturesque town with many eighteenth century homes and narrow, winding streets. Every year, crowds gather on Marblehead Neck to watch the passing sailboat races.

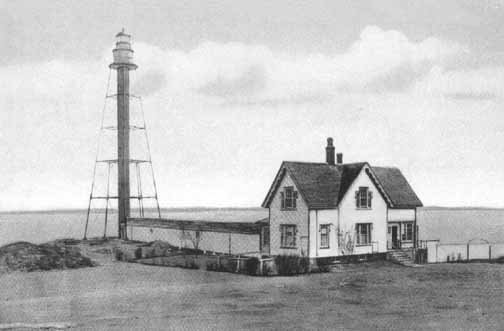

The first Marblehead Light (National Archives)

Many people have speculated how much more scenic this picture would be if Marblehead Light was a traditional lighthouse instead of a metal skeleton tower. Edward Rowe Snow wrote in The Lighthouses of New England, " It is to be realized that lighthouses are for utility and not for beauty, but in this case it is especially unfortunate that beauty and utility were not combined." To many lighthouse fans, Marblehead Light is unique in New England and thus possesses its own charm.

The harbor is situated between the main peninsula of the town and Marblehead Neck, a separate peninsula extending to the east. The neck is connected to the rest of the town by a long sand bar, now a causeway. On August 30, 1831, citizens of Marblehead requested that a lighthouse be erected "on the point of Neck at the entrance to the harbour." Congress appropriated $4,500 for the lighthouse on June 30, 1834, and it was agreed that the northern tip of Marblehead Neck was the most suitable location.

The station was constructed and put in operation on October 10, 1835.

The harbor is situated between the main peninsula of the town and Marblehead Neck, a separate peninsula extending to the east. The neck is connected to the rest of the town by a long sand bar, now a causeway. On August 30, 1831, citizens of Marblehead requested that a lighthouse be erected "on the point of Neck at the entrance to the harbour." Congress appropriated $4,500 for the lighthouse on June 30, 1834, and it was agreed that the northern tip of Marblehead Neck was the most suitable location.

The station was constructed and put in operation on October 10, 1835.

A 23-foot white tower and a keeper's cottage, attached to the tower by a covered walkway, were built near a small fort. The 10 lamps inside the octagonal lantern burned whale oil, and the fixed white light was exhibited from 53 feet above mean high water.

Late 1800s

The first keeper-at $400 yearly was Ezekiel Darling, a native of Duxbury, Massachusetts, and former chief gunner on the U.S.S. Constitution.

He had first gone to sea at the age of eight or nine, and he was wounded in the War of 1812. Darling didn't receive a pension because he was considered "disfigured, but not disabled."

Darling was in charge when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station. The keeper provided a statement for Lewis's report to Congress in 1843:

The tower is leaky about the window casing, there being no recess in the brick for the window frames. The lantern sweats considerably, and formerly I wiped up large quantities of water accumulating from this cause. I now admit as much air as the state of the weather will permit, which in some degree remedies this evil. . . . The dwelling-house is very damp, and the water comes through the walls. The chimneys are all smoky.

He had first gone to sea at the age of eight or nine, and he was wounded in the War of 1812. Darling didn't receive a pension because he was considered "disfigured, but not disabled."

Darling was in charge when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station. The keeper provided a statement for Lewis's report to Congress in 1843:

The tower is leaky about the window casing, there being no recess in the brick for the window frames. The lantern sweats considerably, and formerly I wiped up large quantities of water accumulating from this cause. I now admit as much air as the state of the weather will permit, which in some degree remedies this evil. . . . The dwelling-house is very damp, and the water comes through the walls. The chimneys are all smoky.

Lewis praised Keeper Darling in his report. "Perfect order, cleanliness, and apparent comfort," he wrote, "reign throughout the whole establishment, much to the credit of the keeper."

A sixth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old system of multiple lamps and reflectors in 1857. By 1860, Darling was about 70 and almost blind, and he had to retire after 25 years as keeper.

Jane C. Martin, a Marblehead native said to be the only woman lighthouse keeper on the East Coast at the time she was appointed, succeeded him. She had previously assisted her father, Ambrose Martin, at nearby Baker's Island Light.

The 1869 report of the Lighthouse Board showed lots of activity:

Jane C. Martin, a Marblehead native said to be the only woman lighthouse keeper on the East Coast at the time she was appointed, succeeded him. She had previously assisted her father, Ambrose Martin, at nearby Baker's Island Light.

The 1869 report of the Lighthouse Board showed lots of activity:

The brick oven in the kitchen has been taken away and a closet built in its place; an iron sink set, two chimneys retopped, addition roof reshingled, and wall-paper for two rooms supplied. The walls of covered way have been clapboarded and roof repaired; two window frames of tower have been taken out and reset, packed with paint cement; the privy has been rebuilt, and that and covered way whitewashed; a new ensign, and pipes and linings for stove, supplied.

Circa 1890s

James S. Bailey became keeper in 1872. The old brick dwelling was in increasingly poor condition despite the numerous repairs, and Bailey was in charge when a new two-story, wood-frame house -- typical of many keeper's houses built in New England around that time -- was completed in 1878.

After the prominent Marblehead Neck landowner Ephraim Brown's death in the 1860s, his land, formerly pasture, was sublet and quickly filled with tents and cottages. The property was auctioned in 1872, and the buyers subdivided the property into separate house lots.

Large summer cottages were soon springing up all around the lighthouse. By 1880, the first small tower was obscured by the houses and could not be seen at sea.

After the prominent Marblehead Neck landowner Ephraim Brown's death in the 1860s, his land, formerly pasture, was sublet and quickly filled with tents and cottages. The property was auctioned in 1872, and the buyers subdivided the property into separate house lots.

Large summer cottages were soon springing up all around the lighthouse. By 1880, the first small tower was obscured by the houses and could not be seen at sea.

In 1883, a light was hoisted to the top of a tall mast near the lighthouse. This arrangement bought some time before a taller lighthouse was finally built.

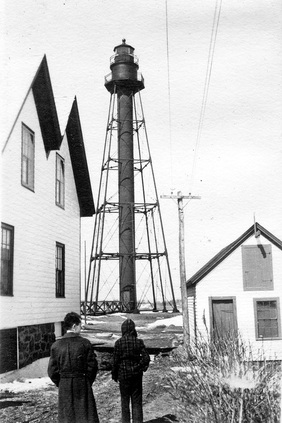

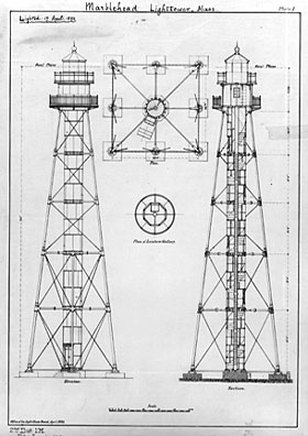

The 1893 annual report of the Lighthouse Board made a case for a new, taller tower. An appropriation of $45,000 was requested for the construction of a brick tower, around 100 feet high, and the request was repeated in the following year. Funds were appropriated, and a contract was awarded in June 1895 for the building of a new lighthouse, but it was not to be a brick tower. Instead, a 105-foot cast-iron skeleton tower was erected at a cost of $8,786.

This is the only lighthouse of its type in the New England states; the nearest similar tower is at Coney Island, New York. There are several of the same type in the mid-Atlantic region, and a few more in Florida.

The lighthouse is composed of eight cast-iron pilings -- resting on eight concrete foundation disks -- connected by supports, with a central iron cylinder that contains a spiral stairway. There are 127 steps to the landing below the lantern level.

When first constructed, the new tower's lantern held a sixth-order Fresnel lens and a kerosene-fueled lamp, and it exhibited a fixed white light 130 feet above mean high water.

The light in the new tower was first illuminated on April 17, 1896. The characteristic was changed in 1922 to fixed red (to stand out against the lights of the town) and was changed again in 1938 to fixed green.

This is the only lighthouse of its type in the New England states; the nearest similar tower is at Coney Island, New York. There are several of the same type in the mid-Atlantic region, and a few more in Florida.

The lighthouse is composed of eight cast-iron pilings -- resting on eight concrete foundation disks -- connected by supports, with a central iron cylinder that contains a spiral stairway. There are 127 steps to the landing below the lantern level.

When first constructed, the new tower's lantern held a sixth-order Fresnel lens and a kerosene-fueled lamp, and it exhibited a fixed white light 130 feet above mean high water.

The light in the new tower was first illuminated on April 17, 1896. The characteristic was changed in 1922 to fixed red (to stand out against the lights of the town) and was changed again in 1938 to fixed green.

Henry T. Drayton was keeper for about 35 years, retiring in the late 1920s after 43 years of duty in the Lighthouse Service. Keeper Drayton was credited with several rescues.

Left: The wife and daughter of Keeper Henry Drayton at the lighthouse in 1917. This photo was taken by Keeper Drayton, who was an accomplished photographer. Courtesy of the Drayton family.

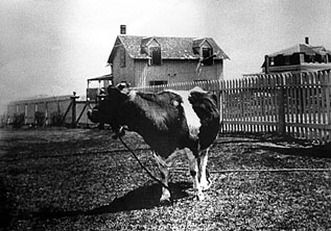

The Draytons kept a cow for milk, and they also had chickens, pigs, and a large garden. Keeper Drayton went to Boston once a month to pick up supplies, including barrels of flour, sugar, and beans.

Twice yearly, a government supply boat arrived with kerosene and other supplies for the light.

Keeper Drayton's daughter, Mary, later recalled the keeper's house as comfortable, with hot-water radiators in every room and running water from the town. Downstairs were a living room, dining room, kitchen, and pantry, and there were four bedrooms and a bath upstairs.

The Draytons kept a cow for milk, and they also had chickens, pigs, and a large garden. Keeper Drayton went to Boston once a month to pick up supplies, including barrels of flour, sugar, and beans.

Twice yearly, a government supply boat arrived with kerosene and other supplies for the light.

Keeper Drayton's daughter, Mary, later recalled the keeper's house as comfortable, with hot-water radiators in every room and running water from the town. Downstairs were a living room, dining room, kitchen, and pantry, and there were four bedrooms and a bath upstairs.

Keeper Drayton held onto the skeleton key that opened the first lighthouse even after the tower was demolished. Many years later, his descendants donated the key -- along with a brass oil can -- to the town for display.

Right: Like many lighthouse families, the Draytons kept a cow at Marblehead Light. Courtesy of the Drayton family.

Harry S. Marden became keeper in May 1938. Just four months later, on September 21, the worst hurricane in New England history belted the coast.

The light went dim as the lighthouse lost its power. Keeper Marden drove his car next to the lighthouse and connected his car's battery to the lighthouse's wiring. He spent the night in the lighthouse, managing to keep the light on until morning.

Harry S. Marden became keeper in May 1938. Just four months later, on September 21, the worst hurricane in New England history belted the coast.

The light went dim as the lighthouse lost its power. Keeper Marden drove his car next to the lighthouse and connected his car's battery to the lighthouse's wiring. He spent the night in the lighthouse, managing to keep the light on until morning.

The station was used by the U.S. Army during World War II and was off limits to the public between 1941 and 1946.

Marblehead Neck resident Chandler Hovey, a well-known yachtsman, purchased the land around the lighthouse and in 1948 donated it to the town. Today Chandler Hovey Park is almost always busy with visitors watching sailboats, flying kites, watching the crashing surf or just enjoying a sunset.

In 1956, the Board of Selectmen of Marblehead submitted a request to the Coast Guard that Marblehead Light be painted white. This request was obviously denied, as the tower remains a kind of military brown.

The keeper's house was torn down in 1959, but a brick oil house still stands. Marblehead Light was automated in 1960 and its sixth-order Fresnel lens was replaced with a modern optic. The lighthouse was sandblasted and repainted in 1993.

The lighthouse is licensed by the Coast Guard to the town of Marblehead. The town's Rotary Club is active in the care of the tower. The light itself is still an active aid to navigation maintained by the Coast Guard.

Left: Bill Conly, historian of Marblehead Lighthouse, with the oil can and key from the family of Keeper Henry Drayton.

In 1956, the Board of Selectmen of Marblehead submitted a request to the Coast Guard that Marblehead Light be painted white. This request was obviously denied, as the tower remains a kind of military brown.

The keeper's house was torn down in 1959, but a brick oil house still stands. Marblehead Light was automated in 1960 and its sixth-order Fresnel lens was replaced with a modern optic. The lighthouse was sandblasted and repainted in 1993.

The lighthouse is licensed by the Coast Guard to the town of Marblehead. The town's Rotary Club is active in the care of the tower. The light itself is still an active aid to navigation maintained by the Coast Guard.

Left: Bill Conly, historian of Marblehead Lighthouse, with the oil can and key from the family of Keeper Henry Drayton.

Above left, the stairs inside the tower. Center, a view from the top. Right, a plaque near the lighthouse, dedicated in September 2002, tells much of the station's history. Below: Aerial video by Baystate Images.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Ezekiel Darling (1835-1860), Jane C. Martin (1860-1862), John Goodwin (1862-1872), James S. Bailey (1872-1892), Albert M. Horter (Hortey?) (1892-1893), Henry T. Drayton (1893-1928), Russell B. Eastman (1928-1930), Edwin C. Rogers (1930-1938), Harry S. Marden (1938-1941), Joseph Barry (caretaker, 1947-1954). Light was under control of U.S. Army 1941-1947.

Ezekiel Darling (1835-1860), Jane C. Martin (1860-1862), John Goodwin (1862-1872), James S. Bailey (1872-1892), Albert M. Horter (Hortey?) (1892-1893), Henry T. Drayton (1893-1928), Russell B. Eastman (1928-1930), Edwin C. Rogers (1930-1938), Harry S. Marden (1938-1941), Joseph Barry (caretaker, 1947-1954). Light was under control of U.S. Army 1941-1947.