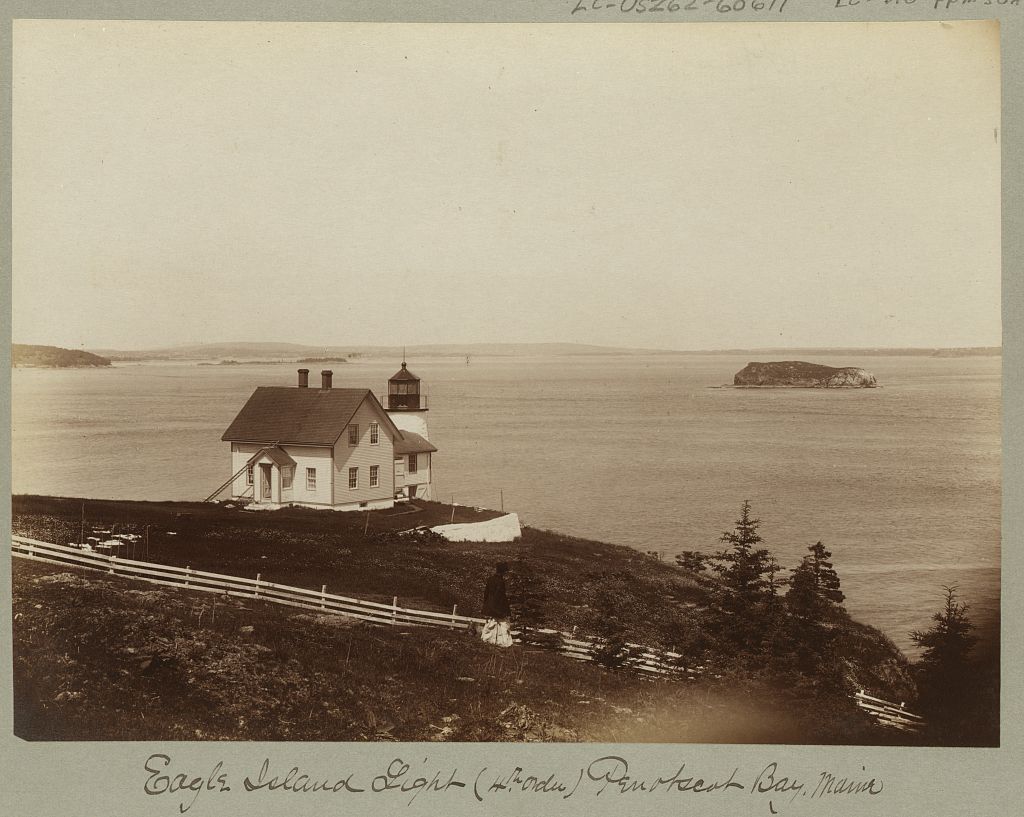

History of Eagle Island Light, Deer Isle, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

For Eagle is a high and noble island which puts a bold front to the sea. . . . Some of the rocks are a coppery green and trees grow out of crevices in the face of the cliffs. Near the water are incipient grottoes. It is a beautiful place. -- Edwin Valentine Mitchell, Anchor to Windward, 1940.

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Two-hundred-sixty-acre Eagle Island, in East Penobscot Bay and about one-and-one-half miles west of Deer Isle, is in the channel followed by many vessels headed north into the Penobscot River and on to Bangor and other ports. As Bangor developed into America's leading lumber port, Congress appropriated $5000 for a light station on Eagle Island in March 1837.

A rubblestone dwelling was built along with a 30-foot-tall conical rubblestone lighthouse tower, and the station went into service in September 1838. The lamps, fueled by whale oil, exhibited a fixed white light 105 feet above mean high water.

The first keeper John Spear, served two separate terms at the lighthouse-from 1839 to 1841 and 1843 to 1848. This was always a family light station with one keeper, and the keeper's wife and children had to help with many of the duties. When Spear died in 1848, his widow served as keeper for a time until a replacement arrived.

A rubblestone dwelling was built along with a 30-foot-tall conical rubblestone lighthouse tower, and the station went into service in September 1838. The lamps, fueled by whale oil, exhibited a fixed white light 105 feet above mean high water.

The first keeper John Spear, served two separate terms at the lighthouse-from 1839 to 1841 and 1843 to 1848. This was always a family light station with one keeper, and the keeper's wife and children had to help with many of the duties. When Spear died in 1848, his widow served as keeper for a time until a replacement arrived.

Unlike many island light stations, Eagle Island was considered a desirable assignment. It wasn't terribly far from the mainland, and there was a sizeable community on the island in summer. Conditions were harsh in the winter, but the island had much to offer in the warmer seasons.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

There were several beaches and freshwater springs, and wild strawberries, cranberries, and raspberries grew in abundance.

Nathan Philbrook was the keeper, at $350 per year, when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis inspected the station for his report to Congress in 1843. Lewis found the mortar in 8the tower "soft and muddy." The tower was very leaky and the walls were coated with ice in winter. Nine panes of glass were broken in the octagonal wrought-iron lantern, and the 10 lamps, each backed by 13-inch parabolic reflector, were out of proper alignment.

William Smith followed Moore as keeper in 1850. According to an inspection report that year, the tower was still leaky and would remain so until it was repointed. The dwelling needed roof repairs and was described as a "smoky concern." A new boathouse was needed, as well as sails and oars for the station's boat.

Major repairs to the tower were finally carried out in 1858. At the same time, a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old lighting apparatus. A cast-iron stairway with 22 steps leading to the lantern was added, replacing the old stone stairway.

The dwelling underwent many changes through the years. The Lighthouse Board reported in 1875, "Owing to the dilapidated condition of the southern end of the keeper's dwelling, the battens were removed, and replaced with new weather-boarding, and the dwelling painted."In 1878, the exterior walls of the dwelling, which had been partially clapboarded, were completely covered and painted. The plastering on the walls and ceilings was repaired in 1880.

Nathan Philbrook was the keeper, at $350 per year, when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis inspected the station for his report to Congress in 1843. Lewis found the mortar in 8the tower "soft and muddy." The tower was very leaky and the walls were coated with ice in winter. Nine panes of glass were broken in the octagonal wrought-iron lantern, and the 10 lamps, each backed by 13-inch parabolic reflector, were out of proper alignment.

William Smith followed Moore as keeper in 1850. According to an inspection report that year, the tower was still leaky and would remain so until it was repointed. The dwelling needed roof repairs and was described as a "smoky concern." A new boathouse was needed, as well as sails and oars for the station's boat.

Major repairs to the tower were finally carried out in 1858. At the same time, a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old lighting apparatus. A cast-iron stairway with 22 steps leading to the lantern was added, replacing the old stone stairway.

The dwelling underwent many changes through the years. The Lighthouse Board reported in 1875, "Owing to the dilapidated condition of the southern end of the keeper's dwelling, the battens were removed, and replaced with new weather-boarding, and the dwelling painted."In 1878, the exterior walls of the dwelling, which had been partially clapboarded, were completely covered and painted. The plastering on the walls and ceilings was repaired in 1880.

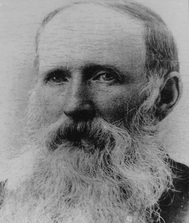

Capt. John Ball, a native of Hancock Point, Maine, became keeper in 1883.

John Ball (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

As a young man, Ball went to sea as a mate on a sailing vessel. He was in charge of a square-rigged ship by the age of 23, and he captained a number of ships sailing from New York to foreign ports. After serving for a time as keeper of Heron Neck Light, he moved with his wife, Amanda (Graves) to Eagle Island. When John Ball retired in 1898, his son Howard followed him as keeper.

Howard Ball remained keeper for another 15 years, and his father lived at the station until his death at the age of 82 in 1905. It was reported that Howard Ball possessed all the "usual abilities needed to survive island living" and that he was "a good neighbor."

Early in 1913, Howard Ball developed pneumonia after helping to guide a Bucksport fishing vessel to safety in a storm. He died on January 31, 1913, and his wife tended the light for about seven weeks until a replacement arrived.

Howard Ball remained keeper for another 15 years, and his father lived at the station until his death at the age of 82 in 1905. It was reported that Howard Ball possessed all the "usual abilities needed to survive island living" and that he was "a good neighbor."

Early in 1913, Howard Ball developed pneumonia after helping to guide a Bucksport fishing vessel to safety in a storm. He died on January 31, 1913, and his wife tended the light for about seven weeks until a replacement arrived.

Charles W. Allen, a native of Lubec, Maine, became keeper in 1919. An islander, when asked to describe Allen, replied, "None better, a good mixer, entered into island affairs-was well liked."

Howard Ball with his wife, Lucy, and three of their children (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

In his spare time, Allen sometimes took guests at the island's Quinn House on fishing and sightseeing trips. The Allens grew oats, peas, and potatoes, and maintained a flower garden. Keeper Allen also kept pigs at the station-in addition to the usual chickens-to augment his family's food supply. Allen was transferred to Doubling Point Light in August 1931.

Frank Earl Bracey Jr., who was originally from Amherst, Maine, was keeper from 1931 until 1945. In 1932, during Bracey's stay, a huge 4,200-pound bronze fog bell was installed in a pyramidal wood-frame bell tower.

The bell struck a double blow once every minute. The keepers would up the clockwork mechanism that operated the striker when the shore of Deer Isle, one-and-one-half-miles to the east, disappeared due to fog. Bracey was the last civilian keeper before the Coast Guard took over the operation of the station.

The life of Edmond Sedgwick, the Coast Guard's officer in charge 1952-55, was described in his 1996 obituary. During the winters, the only people on Eagle Island were Sedgwick and his wife and daughter, and one other family. A mailboat made a weekly visit. "It was a rare experience," his wife, Jeannette Sedgwick, recalled. "Serene. The type of life people crave and can't have."

Frank Earl Bracey Jr., who was originally from Amherst, Maine, was keeper from 1931 until 1945. In 1932, during Bracey's stay, a huge 4,200-pound bronze fog bell was installed in a pyramidal wood-frame bell tower.

The bell struck a double blow once every minute. The keepers would up the clockwork mechanism that operated the striker when the shore of Deer Isle, one-and-one-half-miles to the east, disappeared due to fog. Bracey was the last civilian keeper before the Coast Guard took over the operation of the station.

The life of Edmond Sedgwick, the Coast Guard's officer in charge 1952-55, was described in his 1996 obituary. During the winters, the only people on Eagle Island were Sedgwick and his wife and daughter, and one other family. A mailboat made a weekly visit. "It was a rare experience," his wife, Jeannette Sedgwick, recalled. "Serene. The type of life people crave and can't have."

The light was automated in 1959. The last keeper, Wayne McGraw, was reassigned to a Coast Guard cutter that subsequently went to Vietnam. During its manned years, the station never had electricity; batteries and diesel engines were installed to provide power at the time of automation. An offshore gong buoy replaced the fog bell.

The Coast Guard put all the buildings, except the tower itself, up for auction under the condition that the buyer would remove the buildings from the light station property. Nobody was willing to try this virtually impossible feat, so in 1963 the Coast Guard decided to raze all the buildings except the lighthouse and bell tower.

That decision met with fierce opposition from Erland Quinn, who was raised on the island and owned an adjacent farm that had originally included the lighthouse property. Quinn's wife was the granddaughter of Howard Ball, and she had been born in the keeper's house.

Quinn appealed to Senator Margaret Chase Smith to no avail.

That decision met with fierce opposition from Erland Quinn, who was raised on the island and owned an adjacent farm that had originally included the lighthouse property. Quinn's wife was the granddaughter of Howard Ball, and she had been born in the keeper's house.

Quinn appealed to Senator Margaret Chase Smith to no avail.

In February 1964, a Coast Guard crew out of Rockland demolished the buildings, leaving the old lighthouse tower, the bell tower, and traces of the old foundations.

A. Margaret Bok, wife of a Coast Guardsman who served on the island, told historian Edward Rowe Snow that they "watched the Coast Guard demolish the light station on Eagle Island with heavy hearts." Two sisters, longtime residents of Eagle Island, reportedly watched the demolition with tears streaming down their faces. Former keeper Ralph Banks summed up the demolition: "It was a heartbreaking sight."

When the crew tried to remove the giant 4,200-pound fog bell, they lost control of it and it careened down the cliff into the ocean. A local lobsterman, Walter Shepard, later found the bell and towed it to Great Spruce Head Island, where it was put on display. For unknown reasons, the bell tower was left standing and remains intact today.

Under the Maine Lights Program, ownership of the lighthouse was transferred in 1998 to a nonprofit group, the Eagle Light Caretakers. For more information about the preservation of the lighthouse and bell tower, contact: Eagle Light Caretakers, 305 W 98th St., Apt 4bs, New York, NY 10025.

Keepers : (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Spear (1839-1841, 1843-1848); ? Spear (wife of John, 1848); Nathan Philbrook (1841-1843); Daniel Moore (1849-1850); William Smith (1850-1853); R.C. Clay (1853-1858, 1859-1861); Rodney Witherspoon (1861-1871); A. P. Sweetland (1871-1883); John Ball (1883-1898); Howard T. Ball (1898-1913); Lucy Ball (1913); Edward Stevens Farren (1913-1918); Charles W. Allen (1919-1931); Frank E. Bracey, Jr. (1931-1945); Chester Burnham (Coast Guard, 1945-1946); Calvin H. Curtis (Coast Guard, 1946-1949); Ralph Banks (Coast Guard, 1949-1952); Edmund Sedgewick (Coast Guard, 1952-1955), Roy Louder (Coast Guard, 1955-1956); Edward Le Tendre (Coast Guard, 1956-1957); Wayne McGraw (1957-1959)

When the crew tried to remove the giant 4,200-pound fog bell, they lost control of it and it careened down the cliff into the ocean. A local lobsterman, Walter Shepard, later found the bell and towed it to Great Spruce Head Island, where it was put on display. For unknown reasons, the bell tower was left standing and remains intact today.

Under the Maine Lights Program, ownership of the lighthouse was transferred in 1998 to a nonprofit group, the Eagle Light Caretakers. For more information about the preservation of the lighthouse and bell tower, contact: Eagle Light Caretakers, 305 W 98th St., Apt 4bs, New York, NY 10025.

Keepers : (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Spear (1839-1841, 1843-1848); ? Spear (wife of John, 1848); Nathan Philbrook (1841-1843); Daniel Moore (1849-1850); William Smith (1850-1853); R.C. Clay (1853-1858, 1859-1861); Rodney Witherspoon (1861-1871); A. P. Sweetland (1871-1883); John Ball (1883-1898); Howard T. Ball (1898-1913); Lucy Ball (1913); Edward Stevens Farren (1913-1918); Charles W. Allen (1919-1931); Frank E. Bracey, Jr. (1931-1945); Chester Burnham (Coast Guard, 1945-1946); Calvin H. Curtis (Coast Guard, 1946-1949); Ralph Banks (Coast Guard, 1949-1952); Edmund Sedgewick (Coast Guard, 1952-1955), Roy Louder (Coast Guard, 1955-1956); Edward Le Tendre (Coast Guard, 1956-1957); Wayne McGraw (1957-1959)