History of Gay Head Light, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

The handsome Gay Head Lighthouse stands in one of the most picturesque locations in New England, atop the 130-foot multicolored clay cliffs at the western edge of Martha's Vineyard.

The Englishman Bartholomew Gosnold, the first European to explore the area, called the headland "Dover Cliff" in 1602, after the famous formation on the English Channel. The Gay Head name was in common usage by the 1660s.

Massachusetts State Senator Peleg Coffin of Nantucket requested a lighthouse at Gay Head in 1796 because of the heavy maritime traffic passing through Vineyard Sound. The passage between the Gay Head cliffs and the Elizabeth Islands was treacherous because of the long underwater obstruction called Devil's Bridge that extends out from Gay Head.

Right: The clay in the cliffs below the lighthouse is known for its varied colors.

Massachusetts State Senator Peleg Coffin of Nantucket requested a lighthouse at Gay Head in 1796 because of the heavy maritime traffic passing through Vineyard Sound. The passage between the Gay Head cliffs and the Elizabeth Islands was treacherous because of the long underwater obstruction called Devil's Bridge that extends out from Gay Head.

Right: The clay in the cliffs below the lighthouse is known for its varied colors.

Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton asked for, and received, $5,750 from Congress for the lighthouse.

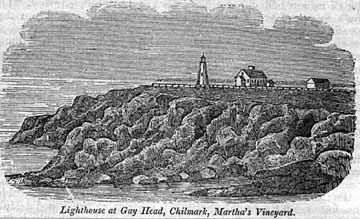

Early engraving of the first Gay Head Lighthouse

A 47-foot (57 feet to the top of the lantern), octagonal wooden lighthouse was erected on a stone base, along with a wood-frame keeper's house, barn, and oil vault. The light went into service on November 18, 1799. The initial keeper, Ebenezer Skiff, was the first white man to live in the town of Gay Head, which was populated by Wampanoag Indians.

There was a fresh water spring near the lighthouse, but since it didn't provide enough water, Skiff had to make a mile's journey with a horse and wagon to retrieve water for his family.

Skiff complained that the cellar of the keeper's house was flooded much of the time, and that clay collecting on the glass made it difficult to keep the lighthouse's lantern clear. Also, to help tend the light while he was on various errands, the keeper sometimes had to hire local Indians for a dollar a day. For his troubles, President Thomas Jefferson awarded Skiff a raise in 1802, from $200 to $250 per year.

There was a fresh water spring near the lighthouse, but since it didn't provide enough water, Skiff had to make a mile's journey with a horse and wagon to retrieve water for his family.

Skiff complained that the cellar of the keeper's house was flooded much of the time, and that clay collecting on the glass made it difficult to keep the lighthouse's lantern clear. Also, to help tend the light while he was on various errands, the keeper sometimes had to hire local Indians for a dollar a day. For his troubles, President Thomas Jefferson awarded Skiff a raise in 1802, from $200 to $250 per year.

Skiff remained at Gay Head for 29 years. He served for a while as a teacher for local children, mostly Gay Head Indians. In 1829, his son, Ellis Skiff, became keeper at $350 per year, a higher salary than most keepers received at the time.

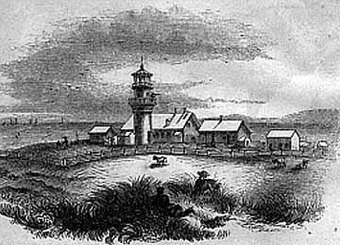

Engraving of the second Gay Head Lighthouse

In 1838, a New Bedford blacksmith rebuilt the lantern and deck, and the tower was lowered by three feet. Earlier, the tower had been cut down by 14 feet to lessen the problem of the light's being obscured by fog. Also during 1838, Lt. Edward W. Carpender examined the station. He reported that the revolving light, which took four minutes to complete an entire revolution, could be seen for more than 20 miles, and that the premises were in good order.

The engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited the station during his landmark survey in the fall of 1842. He described the tower as "decayed in several places," and said the keeper's house was "shaken like a reed" in by storms. Both the tower and house required rebuilding, said Lewis.

Included in Lewis's report was a statement ascribed to Ellis Skiff: "The old clock stopped frequently, and in cold weather would not go, so that I was obliged to let the light stand still, and appear as a fixed light. The reflectors are all worn out. The chambers of my house are not lathed, plastered, or ceiled; and the house is not only cold and uncomfortable, but, from its elevated situation, likely to be blown down, as it shakes fearfully with every gale of wind."

The engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited the station during his landmark survey in the fall of 1842. He described the tower as "decayed in several places," and said the keeper's house was "shaken like a reed" in by storms. Both the tower and house required rebuilding, said Lewis.

Included in Lewis's report was a statement ascribed to Ellis Skiff: "The old clock stopped frequently, and in cold weather would not go, so that I was obliged to let the light stand still, and appear as a fixed light. The reflectors are all worn out. The chambers of my house are not lathed, plastered, or ceiled; and the house is not only cold and uncomfortable, but, from its elevated situation, likely to be blown down, as it shakes fearfully with every gale of wind."

The tower had to be moved back about 75 feet from the edge of the eroding bluff in 1844.

Circa 1880s

Contractor John Mayhew, a contractor from of Edgartown, completed this task. Ellis Skiff remained keeper until he was removed for political reasons in 1845, ending close to a half century of the Skiffs at Gay Head.

An 1852 report on lighthouses in the United States ranked Gay Head Light as the ninth most important seacoast light, the highest rank of any light north of New York. In October of the following year, Joseph T. Pease, the customs collector at Edgartown, wrote to the newly formed Lighthouse Board: "In my opinion, a first class lens light should be erected there as soon as is practicable."

Congress appropriated $30,000 on August 3, 1854, and by the following summer Caleb King was contracted to build the new tower and dwelling.

A first-order Fresnel lens was obtained from the Henry-Lepaute company of Paris. A new 51-foot, conical brick lighthouse was built to hold the enormous lens, which contained 1,008 prisms.

An 1852 report on lighthouses in the United States ranked Gay Head Light as the ninth most important seacoast light, the highest rank of any light north of New York. In October of the following year, Joseph T. Pease, the customs collector at Edgartown, wrote to the newly formed Lighthouse Board: "In my opinion, a first class lens light should be erected there as soon as is practicable."

Congress appropriated $30,000 on August 3, 1854, and by the following summer Caleb King was contracted to build the new tower and dwelling.

A first-order Fresnel lens was obtained from the Henry-Lepaute company of Paris. A new 51-foot, conical brick lighthouse was built to hold the enormous lens, which contained 1,008 prisms.

Gen. David Hunter wrote in Harper's:

Of all the heavenly phenomena that I have had the good fortune to witness -- borealis lights, mock suns, or meteoric showers -- I have never seen anything that, in mystic splendor, equaled the trick of the magic lantern of Gay Head.

An artist's rendering of the wreck of the City of Columbus.

In spite of the powerful light, shipwrecks happened with regularity in the vicinity.The worst of them happened in the early morning of January 19, 1884, when the passenger steamer City of Columbus ran aground on Devil's Bridge, a treacherous ledge reaching out from the Gay Head Cliffs.

Twenty minutes later, 100 persons on board had drowned. Some managed to hold onto the rigging long enough for lighthouse keeper Horatio N. Pease to arrive with a crew of Gay Head Indians in a lifeboat.

A number of people were saved by this crew and by the crew of the Revenue Cutter Dexter, which soon arrived on the scene. The wreck of the City of Columbus remains one of New England's worst marine disasters.

Circa 1890s

William Atchison became keeper in 1890, but had to resign due to a mysterious illness a year later. His replacement, Edward Lowe, died at 44 only a year after becoming keeper.

A few years later, five children of Keeper Crosby L. Crocker died between 1895 and 1901. Another child died at 15 several years later.

Belatedly, it was decided that the cause of all these illnesses was the extreme dampness of the keeper's house. The 1856 brick keeper's house was torn down and replaced by a wooden house in 1902. The new house was built on a much higher foundation so it would remain dry.

Keeper Crocker endured the famous Portland Gale of November 1898. He expected the station's barn to break apart at the height of the storm and prepared to rescue his horse, but the barn remained standing. Crocker had to shovel paths through the snow following the storm -- the only time he ever shoveled snow in 34 years at the station.

A few years later, five children of Keeper Crosby L. Crocker died between 1895 and 1901. Another child died at 15 several years later.

Belatedly, it was decided that the cause of all these illnesses was the extreme dampness of the keeper's house. The 1856 brick keeper's house was torn down and replaced by a wooden house in 1902. The new house was built on a much higher foundation so it would remain dry.

Keeper Crocker endured the famous Portland Gale of November 1898. He expected the station's barn to break apart at the height of the storm and prepared to rescue his horse, but the barn remained standing. Crocker had to shovel paths through the snow following the storm -- the only time he ever shoveled snow in 34 years at the station.

Charles Vanderhoop, an Aquinnah Wampanoag Indian who was born in 1882, became one of the light's most popular keepers. His mother and stepfather had a restaurant built near the lighthouse in the late 1800s, and the restaurant was later owned by Charles and his brother Bert. Charles eventually sold his interest in the restaurant to his brother.

Charles Vanderhoop (U.S. Coast Guard photo)

According to historian Edward Rowe Snow, Charles Vanderhoop and his assistant, Max Attaquin, probably took one-third of a million visitors to the top of Gay Head Light between 1920 and 1933. The wives of Vanderhoop and Attaquin each had two children during their years at the lighthouse.

Charles W. Vanderhoop, Jr., was born at the station in 1921. He is quoted in William Waterway's 2014 book Gay Head Lighthouse: The First Light on Martha's Vineyard:

My father liked showing off the lighthouse to visitors. People were really interested in seeing the lighthouse and its beautiful Fresnel lens. Some weekends we would have thousands of people coming and going all day long. My father would take groups for walks up and down those lighthouse stairs. There are fifty-five stairs from the bottom of the light to the top. He even gave a tour to President Calvin Coolidge just after he left office. My father said that President Coolidge had some people with him who asked questions, but all Coolidge did was nod his head and smile once in a while. My father also gave a tour to the famous movie star comedian Harold Lloyd.

Frank Grieder was keeper from 1937 to 1948. In an interview in 2000, his son Bill Grieder remembered keeping busy at the light station:

There was always some work for me. I used to polish brass. I learned to light the lighthouse, and I taught my mother to do it. There were times when my Dad was sick -- my Mum would go up to light the light or I would go up. Of course we had an assistant keeper, but if you couldn't call on him you did it yourself.

I went up to help whitewash or paint the tower, and mow the lawn of course. Lug the kerosene up in the tower. Polish the lens. It had to be cleaned and dusted all the time. We had a dust cover over that. In the wintertime we used to put glycerin on the outside of the [lantern] glass, so if you got rain it wouldn't ice up.

Charles W. Vanderhoop, Jr., was born at the station in 1921. He is quoted in William Waterway's 2014 book Gay Head Lighthouse: The First Light on Martha's Vineyard:

My father liked showing off the lighthouse to visitors. People were really interested in seeing the lighthouse and its beautiful Fresnel lens. Some weekends we would have thousands of people coming and going all day long. My father would take groups for walks up and down those lighthouse stairs. There are fifty-five stairs from the bottom of the light to the top. He even gave a tour to President Calvin Coolidge just after he left office. My father said that President Coolidge had some people with him who asked questions, but all Coolidge did was nod his head and smile once in a while. My father also gave a tour to the famous movie star comedian Harold Lloyd.

Frank Grieder was keeper from 1937 to 1948. In an interview in 2000, his son Bill Grieder remembered keeping busy at the light station:

There was always some work for me. I used to polish brass. I learned to light the lighthouse, and I taught my mother to do it. There were times when my Dad was sick -- my Mum would go up to light the light or I would go up. Of course we had an assistant keeper, but if you couldn't call on him you did it yourself.

I went up to help whitewash or paint the tower, and mow the lawn of course. Lug the kerosene up in the tower. Polish the lens. It had to be cleaned and dusted all the time. We had a dust cover over that. In the wintertime we used to put glycerin on the outside of the [lantern] glass, so if you got rain it wouldn't ice up.

Another job I used to do was to take people up in the tower. My Mum used to do it too. We didn't have to do it but it was kind of a courtesy. Mostly anybody who stopped in we'd take up.

The light had been converted to kerosene operation in 1885.

The year 1952 saw the end of the kerosene era, as a high-intensity

electric beacon replaced the Fresnel lens. The lens can be seen

today in a structure resembling a short tower and lantern on

the grounds of the Martha's Vineyard Historical Society Museum

in Edgartown. When the display was dedicated in 1952, former

keeper Charles Vanderhoop lighted the lens for the assembled

crowd.

Left: Bill Grieder at Gay Head in the 1940s. Courtesy of Bill Grieder.

Joseph Hindley succeeded Arthur Bettencourt. Hindley would be the last keeper at Gay Head, leaving when the light was fully automated in 1956. Hindley's daughter, Betty, recalled in 2014:

"The wooden house was always snug and warm as the wind howled and the snow fell. We had a big coal furnace. Actually, the Coast Guard filled the coal bins in September 1956 just before we left, then they tore the house down. I wonder what happened to all that coal!"

The dwelling was razed shortly after automation. The Vineyard Environmental Research Institute (V.E.R.I.) leased the lighthouse from the Coast Guard in 1985. The license was transferred to the Martha's Vineyard Museum in 1994. Much work has been done on the tower and grounds in recent years after a period of frequent vandalism.

Left: Bill Grieder at Gay Head in the 1940s. Courtesy of Bill Grieder.

Joseph Hindley succeeded Arthur Bettencourt. Hindley would be the last keeper at Gay Head, leaving when the light was fully automated in 1956. Hindley's daughter, Betty, recalled in 2014:

"The wooden house was always snug and warm as the wind howled and the snow fell. We had a big coal furnace. Actually, the Coast Guard filled the coal bins in September 1956 just before we left, then they tore the house down. I wonder what happened to all that coal!"

The dwelling was razed shortly after automation. The Vineyard Environmental Research Institute (V.E.R.I.) leased the lighthouse from the Coast Guard in 1985. The license was transferred to the Martha's Vineyard Museum in 1994. Much work has been done on the tower and grounds in recent years after a period of frequent vandalism.

Craig Dripps, chair of the Martha's Vineyard Museum's Lighthouse Committee, said in 2007 that rust had caused the gallery surrounding the lantern to lift, allowing rainwater to get inside.

"This moisture not only leaves dampness on the inner walls," according to Dripps, "but also, more seriously, freezes and expands during colder months adversely affecting the integrity of the structure." The Museum is raising funds for a full restoration.

The Town of Aquinnah took ownership of the lighthouse in February 2015. As of that month, the Save the Gay Head Light Committee had raised $2.5 million toward its goal of the $3 million needed to finance a move of the lighthouse away from the edge of the rapidly eroding cliff. The move to safer ground was completed in the spring of 2015.

Visit this site to learn more: Gay Head Lighthouse

The cliffs are closed to the public because of erosion concerns, but the lighthouse is opened seasonally for tours. Click here for the schedule. The best views of the lighthouse and cliffs are from a scenic lookout near the small strip of shops and restaurants at Gay Head.

The Town of Aquinnah took ownership of the lighthouse in February 2015. As of that month, the Save the Gay Head Light Committee had raised $2.5 million toward its goal of the $3 million needed to finance a move of the lighthouse away from the edge of the rapidly eroding cliff. The move to safer ground was completed in the spring of 2015.

Visit this site to learn more: Gay Head Lighthouse

The cliffs are closed to the public because of erosion concerns, but the lighthouse is opened seasonally for tours. Click here for the schedule. The best views of the lighthouse and cliffs are from a scenic lookout near the small strip of shops and restaurants at Gay Head.

Below -- Time lapse video of the lighthouse move in 2015.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Ebenezer Skiff (1799-1828); Ellis Skiff (1828-1845); Samuel Flanders (1845-1849 and 1853-1861); Henry Robinson (1849-1853); Ichabod Norton Luce (1861-1864); Calvin C. Adams (1864-1869); Horatio N. T. Pease (assistant 1863-1869, principal keeper 1869-1890); Frederick Poole (assistant, c. 1884); Calvin M. Adams (assistant c. 1872-?); Frederick H. Lambert (assistant, c. 1870s); Edward P. Lowe (1891-1892); Crosby L. Crocker (assistant c. 1886-1892, principal keeper 1892-1920); Charles W. Vanderhoop (1920-1933); Solomon "Max" Attaquin (1919-1933); James E. Dolby (1933-1937); Frank A. Grieder (1937-1948); Sam Fuller (assistant, c. 1939-1940); Arthur Bettencourt (1948-1950); Joseph Hindley (1950-1956)

Ebenezer Skiff (1799-1828); Ellis Skiff (1828-1845); Samuel Flanders (1845-1849 and 1853-1861); Henry Robinson (1849-1853); Ichabod Norton Luce (1861-1864); Calvin C. Adams (1864-1869); Horatio N. T. Pease (assistant 1863-1869, principal keeper 1869-1890); Frederick Poole (assistant, c. 1884); Calvin M. Adams (assistant c. 1872-?); Frederick H. Lambert (assistant, c. 1870s); Edward P. Lowe (1891-1892); Crosby L. Crocker (assistant c. 1886-1892, principal keeper 1892-1920); Charles W. Vanderhoop (1920-1933); Solomon "Max" Attaquin (1919-1933); James E. Dolby (1933-1937); Frank A. Grieder (1937-1948); Sam Fuller (assistant, c. 1939-1940); Arthur Bettencourt (1948-1950); Joseph Hindley (1950-1956)

Use the player below to hear an interview with Betty Hindley Hatzikon, daughter of Keeper Joseph Hindley, on the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast "Light Hearted."