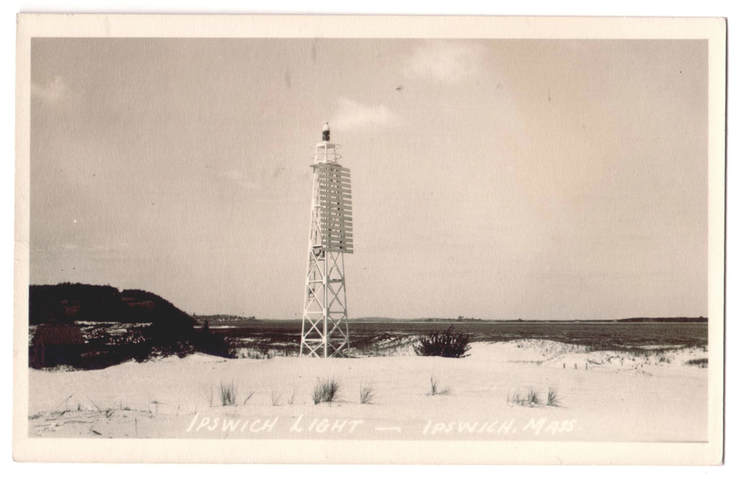

History of Ipswich Range Lights, Ipswich, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Of the thousands of summer visitors who flock to beautiful Crane Beach in Ipswich, Massachusetts, it's likely that few have any inkling that a lighthouse once graced the beach's shifting dunes. For just over a century, a succession of keepers and their families kept watch at the station east of the mouth of the Ipswich River.

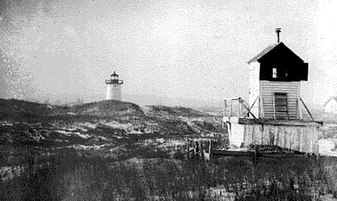

The range lights circa 1900

The first English settlers, led by John Winthrop Jr., arrived in Ipswich around 1633, and fishing and shipbuilding soon prospered. Today, Ipswich is said to have more seventeenth-century homes than any town in America.

Because of increasing maritime traffic in the early 1800s, reliable aids to navigation in the vicinity became a necessity. After a Congressional appropriation of $7,000 in 1837, the federal government paid John Baker and Tristram Brown $10 for four acres of land.

Two lighthouses were built on the stretch of sand now known as Crane Beach, along with a brick, 1 1/2-story dwelling. The 29-foot brick towers -- 542 feet apart from each other on a nearly east-west axis -- originally held 10 lamps and reflectors each and exhibited fixed white lights.

Because of increasing maritime traffic in the early 1800s, reliable aids to navigation in the vicinity became a necessity. After a Congressional appropriation of $7,000 in 1837, the federal government paid John Baker and Tristram Brown $10 for four acres of land.

Two lighthouses were built on the stretch of sand now known as Crane Beach, along with a brick, 1 1/2-story dwelling. The 29-foot brick towers -- 542 feet apart from each other on a nearly east-west axis -- originally held 10 lamps and reflectors each and exhibited fixed white lights.

There were complaints that they could not be distinguished from the pair of fixed lights a few miles to the north on Plum Island, so the western light was soon given a revolving mechanism.

The original rear range light. U.S. Coast Guard photo

The two lights served as a range for mariners coming through the main channel toward the mouth of the Ipswich River. The station began operation on December 1, 1837.

The first keeper was Thomas Smith Greenwood, a native of Boston. Greenwood spent about 13 years in all as keeper between 1837 and 1861, but his tenure was interrupted three times by removal for apparent political reasons, which was common at that time.

Greenwood had gone to sea as a young man and eventually became the captain of clipper ships. He and his wife, Paulina Adams (Thurlow), had eight children. Greenwood also owned a large tract of land to the west of the light station, originally given to him by his wife's family. That land is now operated by the Trustees of Reservations as the Greenwood Farm Reservation.

On December 23, the coast was being battered by the second of what became known as the triple hurricanes of 1839. A Maine schooner, the Deposit, ran aground close to the Ipswich Range Lights. A neighbor informed Keeper Greenwood at dawn, and he ran to the scene to find that the remaining people on the vessel, including the captain's wife, were clinging to the rigging. Two crew members had already died.

The first keeper was Thomas Smith Greenwood, a native of Boston. Greenwood spent about 13 years in all as keeper between 1837 and 1861, but his tenure was interrupted three times by removal for apparent political reasons, which was common at that time.

Greenwood had gone to sea as a young man and eventually became the captain of clipper ships. He and his wife, Paulina Adams (Thurlow), had eight children. Greenwood also owned a large tract of land to the west of the light station, originally given to him by his wife's family. That land is now operated by the Trustees of Reservations as the Greenwood Farm Reservation.

On December 23, the coast was being battered by the second of what became known as the triple hurricanes of 1839. A Maine schooner, the Deposit, ran aground close to the Ipswich Range Lights. A neighbor informed Keeper Greenwood at dawn, and he ran to the scene to find that the remaining people on the vessel, including the captain's wife, were clinging to the rigging. Two crew members had already died.

The situation looked hopeless, but it was the terrified screams of the captain's wife that prompted Greenwood to make a desperate rescue attempt.

The keeper instructed the neighbor, a Mr. Marshall, to hold one end of a 200-foot line. Tying the other end around himself, Greenwood swam through the powerful, icy waves and reached the schooner. Marshall tied the line to a lifeboat, which he then boarded and launched into the breakers. Greenwood pulled the lifeboat, with Marshall in it, to the schooner.

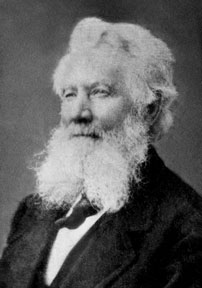

Right: Thomas Smith Greenwood, first keeper of the Ipswich Range Lights. Courtesy of Jim Danforth, all rights reserved.

Greenwood first tried to save Captain Cotterell, who was barely alive. As the captain was being lowered into the lifeboat, a great wave hit and the man was lost, along with the lifeboat. The captain's wife, witnessing her husband's drowning, became hysterical. Greenwood and Marshall convinced the woman to jump from the rigging into their arms. Two of the other survivors managed to reach shore by clinging to wreckage, while Greenwood, Marshall and the captain's wife were carried safely to shore by a great wave. Captain Cotterell and the sailors who died were buried in Ipswich a few days later, with 16 sea captains serving as pallbearers.

Joseph Dennis became keeper in 1841. In his landmark 1843 report, engineer I. W. P. Lewis was critical of the construction methods used for the station. Keeper Dennis told Lewis that he had hired a man to make an embankment around the dwelling "to prevent the sand from blowing away, and also to keep the vegetables from freezing in the cellar."

Right: Thomas Smith Greenwood, first keeper of the Ipswich Range Lights. Courtesy of Jim Danforth, all rights reserved.

Greenwood first tried to save Captain Cotterell, who was barely alive. As the captain was being lowered into the lifeboat, a great wave hit and the man was lost, along with the lifeboat. The captain's wife, witnessing her husband's drowning, became hysterical. Greenwood and Marshall convinced the woman to jump from the rigging into their arms. Two of the other survivors managed to reach shore by clinging to wreckage, while Greenwood, Marshall and the captain's wife were carried safely to shore by a great wave. Captain Cotterell and the sailors who died were buried in Ipswich a few days later, with 16 sea captains serving as pallbearers.

Joseph Dennis became keeper in 1841. In his landmark 1843 report, engineer I. W. P. Lewis was critical of the construction methods used for the station. Keeper Dennis told Lewis that he had hired a man to make an embankment around the dwelling "to prevent the sand from blowing away, and also to keep the vegetables from freezing in the cellar."

Most importantly, Lewis pointed out that since the channel had shifted, the range lights no longer provided proper guidance into the Ipswich River. A mariner using the range lights "would run ashore in the south spit of Plum Island."

Benjamin Ellsworth was appointed keeper in 1861. Ellsworth's wife died soon after he took the position, and the keeper's daughter, Susan, kept house at the station. Susan was the youngest of 12 children. Three sons of Keeper Ellsworth fought in the Civil War, and all three returned safely.

Benjamin Ellsworth would remain at the station until his death in 1902.

Left: Keeper Benjamin Ellsworth. Courtesy of Edith Sturtevant.

Ellsworth was responsible for several rescues of shipwreck victims during his long stay. In October 1863, he went to the aid of the passengers of an English schooner that had run aground. He later said he could "scarcely help from laughing" when he reached the wreck, because the passengers thought he was there to rob them. One of the passengers, a lawyer, had to convince the others to go with Ellsworth, and they all survived.

Benjamin Ellsworth would remain at the station until his death in 1902.

Left: Keeper Benjamin Ellsworth. Courtesy of Edith Sturtevant.

Ellsworth was responsible for several rescues of shipwreck victims during his long stay. In October 1863, he went to the aid of the passengers of an English schooner that had run aground. He later said he could "scarcely help from laughing" when he reached the wreck, because the passengers thought he was there to rob them. One of the passengers, a lawyer, had to convince the others to go with Ellsworth, and they all survived.

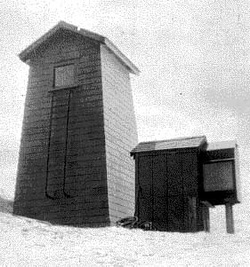

At some point before 1867, the front light was replaced by a shanty-like affair known as the "bug light." In 1867, the front light had to be moved 550 feet as the channel had greatly shifted.

One of the later range lights, known as a "bug light"

A great deal of repairs to the dwelling were carried out in the 1867-69 period, and the 989-foot plank walkway from the rear light to the dwelling was rebuilt.

By 1878, the rear tower was badly cracked. It was replaced by a 45-foot, conical cast-iron tower in 1881, similar to several built in New England during the 1870s and 1880s.

The changes in the contours of the beach have been dramatic. According to Charles Wendell Townsend's 1913 book, Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes, the corner of the lighthouse property was originally about 82 feet from the high water mark; in 1911, the same spot was 1,090 feet from the water.

Townsend wrote that when Keeper Ellsworth first took charge at the range lights he could stand at the top of the main light, then close to the water's edge, and converse with men in boats offshore.

The front range light was discontinued in November 1932 and the rear light was automated at the same time. The last official keeper was Carl Delano Hill, a Lighthouse Service veteran who spent a decade at the Ipswich station.

For some years after this, an unofficial "keeper" or caretaker lived at the station with his family. These caretakers were paid by the nearby Crane Estate to do work on the estate during the day, and they replaced bulbs in the rear light when needed. From 1932 to 1934 the caretaker was Frode Nordquist, and from 1934 to 1942 it was Leroy F. H. Lane. Lane lived at the station with his wife, Angie (Harris) Lane and their three children.

Lane's daughter Virginia Lane Stansfield later wrote a memoir describing life at the lighthouse. "The road to the beach was very poor them and we often had to walk a dike across the causeway to get to the house and to the school bus stop when the tide was high because the road flooded. I remember one storm when the waves broke through the dunes and we found ourselves with the waves breaking on one side of the house and then rolling on past the house leaving us in the middle. The house was well built with one-foot thick walls of brick so it survived storms well." Virginia recalled the sand cutting into her legs during the famous hurricane of 1938, but inside the house there was silence because of the thick walls.

One Christmas season in the 1930s, "Flying Santa" Edward Rowe Snow was due to drop presents from a plane for the keeper and his family. A group of children had gathered in the house in anticipation of Santa's visit. As the scheduled time approached, Lane called to his wife, "Has he come yet, dear?" At that very moment there was a crash from upstairs. The package dropped by Snow had made a direct hit and broke through a skylight. "Yes, dear, we can start the party now," answered Angie.

The Lanes inherited a black-and-white cat named Peter from the previous keeper. Peter was semi-wild and would catch rabbits, snakes, and mice, but he come inside for shelter in the winter. He would also follow the children to the school bus stop in the morning and follow them home in the afternoon.

Another interesting memory was the wreck of a three-masted schooner from Maine, the Thomas H. Lawrence, that came aground on the beach during a storm in September 1839, close to the centennial of the wreck of the Deposit. Nobody died in the accident, and Angie Lane made the survivors sandwiches in the kitchen of the keeper's house. The schooner was later pulled off the beach by tugboats.

By 1878, the rear tower was badly cracked. It was replaced by a 45-foot, conical cast-iron tower in 1881, similar to several built in New England during the 1870s and 1880s.

The changes in the contours of the beach have been dramatic. According to Charles Wendell Townsend's 1913 book, Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes, the corner of the lighthouse property was originally about 82 feet from the high water mark; in 1911, the same spot was 1,090 feet from the water.

Townsend wrote that when Keeper Ellsworth first took charge at the range lights he could stand at the top of the main light, then close to the water's edge, and converse with men in boats offshore.

The front range light was discontinued in November 1932 and the rear light was automated at the same time. The last official keeper was Carl Delano Hill, a Lighthouse Service veteran who spent a decade at the Ipswich station.

For some years after this, an unofficial "keeper" or caretaker lived at the station with his family. These caretakers were paid by the nearby Crane Estate to do work on the estate during the day, and they replaced bulbs in the rear light when needed. From 1932 to 1934 the caretaker was Frode Nordquist, and from 1934 to 1942 it was Leroy F. H. Lane. Lane lived at the station with his wife, Angie (Harris) Lane and their three children.

Lane's daughter Virginia Lane Stansfield later wrote a memoir describing life at the lighthouse. "The road to the beach was very poor them and we often had to walk a dike across the causeway to get to the house and to the school bus stop when the tide was high because the road flooded. I remember one storm when the waves broke through the dunes and we found ourselves with the waves breaking on one side of the house and then rolling on past the house leaving us in the middle. The house was well built with one-foot thick walls of brick so it survived storms well." Virginia recalled the sand cutting into her legs during the famous hurricane of 1938, but inside the house there was silence because of the thick walls.

One Christmas season in the 1930s, "Flying Santa" Edward Rowe Snow was due to drop presents from a plane for the keeper and his family. A group of children had gathered in the house in anticipation of Santa's visit. As the scheduled time approached, Lane called to his wife, "Has he come yet, dear?" At that very moment there was a crash from upstairs. The package dropped by Snow had made a direct hit and broke through a skylight. "Yes, dear, we can start the party now," answered Angie.

The Lanes inherited a black-and-white cat named Peter from the previous keeper. Peter was semi-wild and would catch rabbits, snakes, and mice, but he come inside for shelter in the winter. He would also follow the children to the school bus stop in the morning and follow them home in the afternoon.

Another interesting memory was the wreck of a three-masted schooner from Maine, the Thomas H. Lawrence, that came aground on the beach during a storm in September 1839, close to the centennial of the wreck of the Deposit. Nobody died in the accident, and Angie Lane made the survivors sandwiches in the kitchen of the keeper's house. The schooner was later pulled off the beach by tugboats.

By 1938, the sand was so high around the tower that maintenance personnel had to enter through a window high up on the tower. It was decided that a simple steel skeleton tower would be easier to maintain, and there would be no worry if sand built up around its base.

Left: The 1881 rear range tower. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell.

When the Coast Guard announced that it planned to remove the lighthouse (the former rear range tower) in 1938, many letters were sent in protest.

Susan Ellsworh, the 90-year old daughter of Keeper Benjamin Ellsworth, was one of the loudest voices of opposition. The local complaints could not stop the wheels of government, and the lighthouse was soon gone.

In 1939, the cast-iron lighthouse was floated by barge to Edgartown in Martha's Vineyard to replace an earlier structure that had been badly damaged in the hurricane of 1938.

The lighthouse in Ipswich was replaced by a skeleton tower.

After some years of use by town organizations including the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, the keeper's house was destroyed by a suspicious fire in 1973. Other than the decidedly unpicturesque modern tower, there is no surviving reminder of the Ipswich Light Station on its former site.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

T. S. Greenwood (1838-1841, 1847-1849, and 1853-1861); Joseph Dennis (1841-1843); Ebenezer Pulsifer (1843-1847); John I. Philbrook (1849-1853); Benjamin Ellsworth (1861-1902); Thomas J. Creed (1910-1912); George A. Howard (1912-1916); Alfred A. Howard (1916-1919); G. F. Woodman Jr. (1919-1922); Carl Delano Hill (1922-1932); Frode Nordquist (caretaker, 1932-1934); Leroy F. H. Lane (caretaker, 1934-1942)