History of Deer Island Thorofare Light, Stonington, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Deer Island Thorofare—a narrow passage south of Stonington in East Penobscot Bay—was a busy waterway by the mid-nineteenth century, with granite quarries booming in the area and a strong fishing industry.

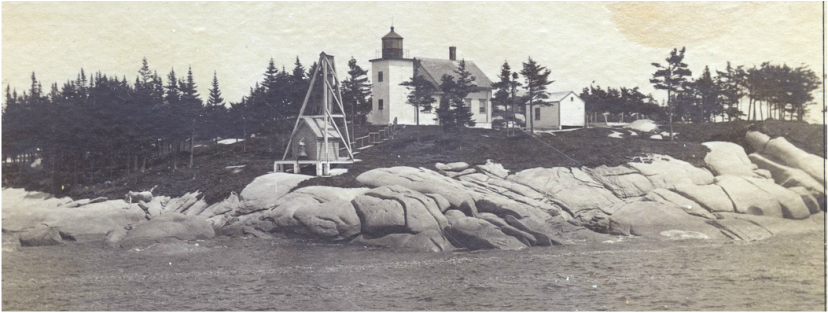

Circa 1859 (National archives)

Six-acre Mark Island, about a mile offshore from Stonington at the western entrance to the passage, was an ideal location for a lighthouse to aid local navigation.

Congress appropriated $5,000 for that purpose in August 1856, and the island was soon purchased from David Thurlow for $175.

The 25-foot-tall, square brick tower was fitted with a fourth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light 52 feet above mean high water, which was first lighted on New Year’s Day in 1858.

The tower was attached to a one-and-one-half-story, wood-frame keeper’s dwelling. An unusual aspect of this lighthouse is that the square tower is round on the inside, with a round spiral stairway. (Thanks to Chip Ross for the heads up on this.)

The only other Maine lighthouse that fits this description is Fort Point Light in Stockton Springs.

Congress appropriated $5,000 for that purpose in August 1856, and the island was soon purchased from David Thurlow for $175.

The 25-foot-tall, square brick tower was fitted with a fourth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light 52 feet above mean high water, which was first lighted on New Year’s Day in 1858.

The tower was attached to a one-and-one-half-story, wood-frame keeper’s dwelling. An unusual aspect of this lighthouse is that the square tower is round on the inside, with a round spiral stairway. (Thanks to Chip Ross for the heads up on this.)

The only other Maine lighthouse that fits this description is Fort Point Light in Stockton Springs.

David Thurlow’s second cousin, Thomas Colby Small, became the first keeper. Small had suffered an injury at sea when he fell from the rigging of a ship, ending his seafaring life. Small and his wife, Elizabeth Ann (Fifield), had 14 children.

The round stairs inside the square tower. Photo by Chip Ross.

Samuel E. Holden of Deer Isle, a former farmer and teacher who had been disabled in the Civil War, became the keeper in 1868. Holden’s wife, Melissa (Colby), was his former student.

Melissa had four children with her first husband, who had died, and Holden also had four children by a previous marriage. Samuel and Melissa’s only son, Amasa, was born at the light station in May 1872 with the help of Melissa’s older children, while her husband was ashore.

When Samuel fell ill in early 1874, Melissa tended the light while caring for her husband and children. Samuel Holden died at the end of March 1874. A letter from the local lighthouse superintendent recommended the appointment of Melissa Holden as keeper: “During the sickness of her husband, Mrs. Holden tended this light for about two months to the entire satisfaction of the public. She is strongly recommended as a capable and efficient woman every way competent to take charge of the station. She has five children dependent on her for support, and her husband was the owner of a homestead which is mortgaged for a small amount.”

Melissa Colby Holden won the appointment. A few stories survive about the feisty woman’s lighthouse keeping days. The custom at that time was to keep the place settings on the fully set dining table covered with a cloth between meals, and Melissa also kept a loaded pistol under the cloth. If a stranger landed at the island, she stayed near the table and the concealed weapon. “I never had to use the gun,” she later said, proudly. It was reported, however, that she once emptied a chamber pot on the heads of some unlucky intruders.

During her stay, the fuel for the light was changed from lard oil to kerosene. Melissa Holden remained keeper for only a little more than two years; James A. Morris succeeded her in 1876. After remarriage and four more children, Melissa died in Stonington in 1920 at the age of 76.

A wood-frame fog bell tower was added to the station in October 1884, with its automatic striking machinery sounding a double blow every 15 seconds. One keeper later jokingly claimed that he “had to work twice as hard as any other keeper on the coast of Maine” to produce the double blow. The bell tower was painted red until June 1921, when it was painted white. Other changes included the addition of a boathouse (1877), and an oil house (1895).

Melissa had four children with her first husband, who had died, and Holden also had four children by a previous marriage. Samuel and Melissa’s only son, Amasa, was born at the light station in May 1872 with the help of Melissa’s older children, while her husband was ashore.

When Samuel fell ill in early 1874, Melissa tended the light while caring for her husband and children. Samuel Holden died at the end of March 1874. A letter from the local lighthouse superintendent recommended the appointment of Melissa Holden as keeper: “During the sickness of her husband, Mrs. Holden tended this light for about two months to the entire satisfaction of the public. She is strongly recommended as a capable and efficient woman every way competent to take charge of the station. She has five children dependent on her for support, and her husband was the owner of a homestead which is mortgaged for a small amount.”

Melissa Colby Holden won the appointment. A few stories survive about the feisty woman’s lighthouse keeping days. The custom at that time was to keep the place settings on the fully set dining table covered with a cloth between meals, and Melissa also kept a loaded pistol under the cloth. If a stranger landed at the island, she stayed near the table and the concealed weapon. “I never had to use the gun,” she later said, proudly. It was reported, however, that she once emptied a chamber pot on the heads of some unlucky intruders.

During her stay, the fuel for the light was changed from lard oil to kerosene. Melissa Holden remained keeper for only a little more than two years; James A. Morris succeeded her in 1876. After remarriage and four more children, Melissa died in Stonington in 1920 at the age of 76.

A wood-frame fog bell tower was added to the station in October 1884, with its automatic striking machinery sounding a double blow every 15 seconds. One keeper later jokingly claimed that he “had to work twice as hard as any other keeper on the coast of Maine” to produce the double blow. The bell tower was painted red until June 1921, when it was painted white. Other changes included the addition of a boathouse (1877), and an oil house (1895).

For years, mail deliveries to Mark Island were rather complicated. A storekeeper in Rockland would give newspapers and the mail to the captain of some vessel heading east.

When the vessel approached Mark Island, the bundle would be tossed into the water. The keeper would swiftly row out to retrieve the package.

John Purington was keeper from 1912 to 1916, when he “swapped” light stations with Allen Carter Holt at Nash Island. Holt’s wife had home-schooled their children on Nash Island, but when they moved to Mark Island the children attended Stonington High School. They boarded in town during the winter, but often traveled back and forth to the island in fall and spring via on the keeper’s motorized dory.

The children, Carl and Louise, later recalled passing their time on the island by beachcombing, playing cards, and reading aloud.

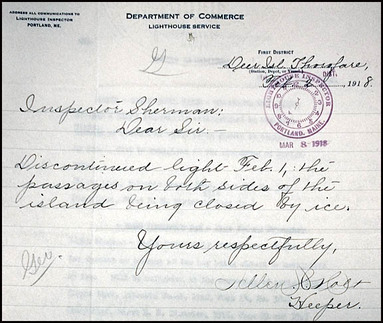

Right: This letter written on February 2, 1918, by Keeper Allen Holt, explains that he had extinguished the light because the shipping channels had been closed due to ice. The ice broke up and he re-established the light on February 8. (National Archives)

John Purington was keeper from 1912 to 1916, when he “swapped” light stations with Allen Carter Holt at Nash Island. Holt’s wife had home-schooled their children on Nash Island, but when they moved to Mark Island the children attended Stonington High School. They boarded in town during the winter, but often traveled back and forth to the island in fall and spring via on the keeper’s motorized dory.

The children, Carl and Louise, later recalled passing their time on the island by beachcombing, playing cards, and reading aloud.

Right: This letter written on February 2, 1918, by Keeper Allen Holt, explains that he had extinguished the light because the shipping channels had been closed due to ice. The ice broke up and he re-established the light on February 8. (National Archives)

Elmer Conary was keeper for several years from the 1920s to 1935. A 1929 article by Harry Buxton called Conary “one of the most efficient keepers in the lighthouse service of the United States.”

National Archives

The article mentioned that Conary and his wife, Gertrude, had great success growing potatoes and canning wild strawberries.

According to the story, the keeper and his wife split the work at the light station “on a fifty-fifty basis, which should furnish food for thought for some of our modern married couples.” Elmer did some of the cooking and housework, and Gertrude frequently helped with painting and odd jobs. She also made rugs and quilts and home- schooled their youngest daughter, Alice. On occasion, when her husband was ill, Gertrude Conary filled in as keeper.

According to the story, the keeper and his wife split the work at the light station “on a fifty-fifty basis, which should furnish food for thought for some of our modern married couples.” Elmer did some of the cooking and housework, and Gertrude frequently helped with painting and odd jobs. She also made rugs and quilts and home- schooled their youngest daughter, Alice. On occasion, when her husband was ill, Gertrude Conary filled in as keeper.

Travel from Mark Island to Stonington was sometimes difficult in winter, when ice clogged the channel. In February 1935, Elmer Conary suffered an apparent heart attack during a period when boat travel was practically impossible.

Joseph Muise. (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

Someone, probably Gertrude Conary, sent up flares for about three hours. The flares attracted attention from the mainland, and a tug set out for the island with a local doctor, B. L. Noyes. The tug butted through the ice for about three hours and finally reached Mark Island. Dr. Noyes treated the keeper on the island, and then Conary was carried aboard the tug.

When the vessel reached Stonington Harbor, the ice was too thick to continue. The sick man was transported in a lifeboat through a narrow channel in the ice.

Conary recuperated with his family on the mainland; his apparent heart attack might have been a simple anxiety attack or, as one newspaper stated, “acute indigestion.” Dr. Noyes said the next day, “We brought him to shore and he’s getting along fine now. He was worried out there for fear he was going to be sick and frozen in—isolated out there—at the same time."

Joseph Muise, who went on to serve 15 years at Burnt Island Light, succeeded Conary as keeper. His son Willard assisted and served as relief keeper when needed.

When the vessel reached Stonington Harbor, the ice was too thick to continue. The sick man was transported in a lifeboat through a narrow channel in the ice.

Conary recuperated with his family on the mainland; his apparent heart attack might have been a simple anxiety attack or, as one newspaper stated, “acute indigestion.” Dr. Noyes said the next day, “We brought him to shore and he’s getting along fine now. He was worried out there for fear he was going to be sick and frozen in—isolated out there—at the same time."

Joseph Muise, who went on to serve 15 years at Burnt Island Light, succeeded Conary as keeper. His son Willard assisted and served as relief keeper when needed.

Alvah Robinson, a native of Harrington, Maine, was keeper from 1936 to 1945. The book Anchor to Windward by Edwin Valentine Mitchell described a visit of the vessel Sunbeam to Mark Island, circa 1939.

National Archives

The Sunbeam visited lighthouses and other locations along the coast on behalf of the Maine Seacoast Mission, bringing literature and supplies to people in remote places.

I could see the light keeper, Alvah Robinson . . . as he came down from the lighthouse in his rubber boots onto the rocks at the best landing place... A small black-and-tan dog nearly went mad with excitement as we neared the shore. Without any passing motor cars to bark at, he barks at passing boats, rinning along the rocks in vain pursuit of them. . . . The keeper caught the bow of the skiff and there was a scramble to get out. I was a fraction of a second late. With the bow in the air, a wave which must have come all the way from Baffin's Land broke over the stern, drenching me and the magazines. . .

The dog cut circles around us as we trudged up to the kitchen door of the lighthouse, where we were cordially welcomed by Mrs. Robinson and Miss Rachel Robinson, who seemed pleased with the magazines despite their damp condition. The pots and pans in the kitchen shone, and the floors in the house were like mirrors. I had the feeling that here was a perfectly kept light station.

I could see the light keeper, Alvah Robinson . . . as he came down from the lighthouse in his rubber boots onto the rocks at the best landing place... A small black-and-tan dog nearly went mad with excitement as we neared the shore. Without any passing motor cars to bark at, he barks at passing boats, rinning along the rocks in vain pursuit of them. . . . The keeper caught the bow of the skiff and there was a scramble to get out. I was a fraction of a second late. With the bow in the air, a wave which must have come all the way from Baffin's Land broke over the stern, drenching me and the magazines. . .

The dog cut circles around us as we trudged up to the kitchen door of the lighthouse, where we were cordially welcomed by Mrs. Robinson and Miss Rachel Robinson, who seemed pleased with the magazines despite their damp condition. The pots and pans in the kitchen shone, and the floors in the house were like mirrors. I had the feeling that here was a perfectly kept light station.

The three members of the Robinson family are the only persons on the island, and I think we were the first visitors in five or six months. Mr. Robinson said that he managed to get ashore for mail and supplies about once a week, but I gathered that Mrs. Robinson and her daughter, a girl of perhaps seventeen, had not been to the mainland for several months.

Keeper Alvah Robinson and his grandson

Mrs. Robinson said that she and Rachel crocheted and made quilts and went to bed early. They had been at the lighthouse four years. Before that they were at Matinicus Rock for six years... I gained the impression that while Matinicus Rock is an offshore light it was less lonely for the Robinsons because of the other families stationed there.

In 1946, Coast Guard keeper Ralph Stanley Andrews slipped while stepping out of a motorboat into a dinghy and was partially paralyzed. Andrews' wife and stepmother kept the light for three days before a relief keeper arrived. Andrews returned to duty -- on crutches -- after 11 days.

In the summer of 1956, the light station was restricted to men only after nearly a century as a family station. In September 1958, an explosion and fire badly damaged the keeper's house. The light was subsequently automated and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern lens.

The Coast Guard keeper was removed and all the buildings except the lighthouse tower were destroyed. An automatic horn replaced the fog bell. Sometime in the 1970s, the fog bell was removed from Mark Island.

On December 15, 1997, the Maine Lighthouse Selection Committee, formed to oversee the transfer of 35 Maine lighthouses under the Maine Lights Program, announced that Deer Island Thorofare Light would be turned over by the Coast Guard to the Island Heritage Trust.

Dr. Ken Crowell and his wife, Marnie Reed Crowell, have done a great deal to further the preservation of the lighthouse on Mark Island. Dr. Crowell is a professor emeritus of biology at St. Lawrence University in New York; the Crowells first became familiar with Mark Island over 30 years ago when they studied mice populations on the island. Marnie Reed Crowell has written a booklet on the history of Deer Island Thorofare Light.

The Island Heritage Trust held a celebratory dinner on March 14, 1998, and the guest of honor was Ralph Stanley Andrews, Sr., keeper of the lighthouse in the 1940s. About 30 descendants of the lighthouse's keepers attended the event. Memorabilia was displayed and items were auctioned to help pay for the upkeep of the lighthouse.

The Island Heritage Trust maintains the island as a wildlife refuge. Mark Island's birds include bald eagles and nesting eider ducks.

The lighthouse remains an active aid to navigation. It can be seen distantly from the mainland and a somewhat better view is available from a sightseeing cruise from Stonington offered by the Isle au Haut Company. Stonington is worth a visit as one of the most unspoiled fishing villages in Maine.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Thomas Colby Small (1857-1861); Paul Thurlow (1861-1864); Levi Babbidge (1864-1868); Samuel E. Holden (1868-1874); Melissa Colby Holden (1874-1876); James A. Morris (1876-1881); Charles A. Gott (1881-1887); Howard M. Gilley (1887-1896); Will C. Tapley (1896-1905); Charles B. Stanley (1905-?); John Purington (1912-1916); Allen Carter Holt (1916-c. 1920); Henry Smith (?); Stanley Kimball (19??-?); Elmer E. Conary (c. 1929-1935); Joseph Muise (1935-36); Alvah Robinson (1936-1945); Ralph Stanley Andrews, Sr. (Coast Guard, 1945-1948); Irving Hines (Coast Guard, 1948-?); Joe Friend (Coast Guard, 1953-?); James McPherson (Coast Guard, 195?-?); Richard Kwapiszewski (Coast Guard, c. 1953-1958).

In 1946, Coast Guard keeper Ralph Stanley Andrews slipped while stepping out of a motorboat into a dinghy and was partially paralyzed. Andrews' wife and stepmother kept the light for three days before a relief keeper arrived. Andrews returned to duty -- on crutches -- after 11 days.

In the summer of 1956, the light station was restricted to men only after nearly a century as a family station. In September 1958, an explosion and fire badly damaged the keeper's house. The light was subsequently automated and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern lens.

The Coast Guard keeper was removed and all the buildings except the lighthouse tower were destroyed. An automatic horn replaced the fog bell. Sometime in the 1970s, the fog bell was removed from Mark Island.

On December 15, 1997, the Maine Lighthouse Selection Committee, formed to oversee the transfer of 35 Maine lighthouses under the Maine Lights Program, announced that Deer Island Thorofare Light would be turned over by the Coast Guard to the Island Heritage Trust.

Dr. Ken Crowell and his wife, Marnie Reed Crowell, have done a great deal to further the preservation of the lighthouse on Mark Island. Dr. Crowell is a professor emeritus of biology at St. Lawrence University in New York; the Crowells first became familiar with Mark Island over 30 years ago when they studied mice populations on the island. Marnie Reed Crowell has written a booklet on the history of Deer Island Thorofare Light.

The Island Heritage Trust held a celebratory dinner on March 14, 1998, and the guest of honor was Ralph Stanley Andrews, Sr., keeper of the lighthouse in the 1940s. About 30 descendants of the lighthouse's keepers attended the event. Memorabilia was displayed and items were auctioned to help pay for the upkeep of the lighthouse.

The Island Heritage Trust maintains the island as a wildlife refuge. Mark Island's birds include bald eagles and nesting eider ducks.

The lighthouse remains an active aid to navigation. It can be seen distantly from the mainland and a somewhat better view is available from a sightseeing cruise from Stonington offered by the Isle au Haut Company. Stonington is worth a visit as one of the most unspoiled fishing villages in Maine.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Thomas Colby Small (1857-1861); Paul Thurlow (1861-1864); Levi Babbidge (1864-1868); Samuel E. Holden (1868-1874); Melissa Colby Holden (1874-1876); James A. Morris (1876-1881); Charles A. Gott (1881-1887); Howard M. Gilley (1887-1896); Will C. Tapley (1896-1905); Charles B. Stanley (1905-?); John Purington (1912-1916); Allen Carter Holt (1916-c. 1920); Henry Smith (?); Stanley Kimball (19??-?); Elmer E. Conary (c. 1929-1935); Joseph Muise (1935-36); Alvah Robinson (1936-1945); Ralph Stanley Andrews, Sr. (Coast Guard, 1945-1948); Irving Hines (Coast Guard, 1948-?); Joe Friend (Coast Guard, 1953-?); James McPherson (Coast Guard, 195?-?); Richard Kwapiszewski (Coast Guard, c. 1953-1958).