History of Ram Island Light, Boothbay Harbor, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Ram Island’s fascinating history is replete with tales of ghosts and shipwrecks. The island—likely probably named for the large number of sheep (including rams) pastured there in centuries past—is part of a small archipelago of several islands, just west of the northern tip of the much larger Fisherman Island, on the south side of Fisherman Island Passage.

Late 1800s (U.S. Coast Guard photo)

The history of aids to navigation on Ram Island began in the mid-1800s when a fisherman, after narrowly escaping the dangerous rocks near the island, began hanging a lantern at night for the benefit of local mariners.

The fisherman left the area after a number of years and the lantern was kept by a second keeper, then a third.

The third lantern keeper anchored a dory and rigged the lamp in its bow. It became the custom for the last fisherman coming into the harbor each day to light the lantern. This ended when the dory was smashed in a storm.

The fisherman left the area after a number of years and the lantern was kept by a second keeper, then a third.

The third lantern keeper anchored a dory and rigged the lamp in its bow. It became the custom for the last fisherman coming into the harbor each day to light the lantern. This ended when the dory was smashed in a storm.

For a time, the lone resident of Fisherman's Island maintained a lantern. Apparently the light he displayed was too weak, causing an increase in wrecks.

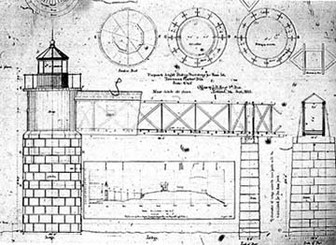

Plans for the lighthouse (U.S. Coast Guard)

Once when a schooner was in danger of coming up on the rocks the fisherman got a line to the vessel and the crew managed to escape to the shore. Soon there was another wreck in which most of the crew were killed.

For some years after this, there was no light on Ram Island. Locals talked of ghosts that warned vessels away from the dangerous rocks. Robert Thayer Sterling, in his book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, tells several eerie stories of Ram Island.

One captain swore he was warned by a fog whistle at Ram Island during a snowstorm, which was impossible since there was no such signal there. Another fisherman was in danger of running into the rocks when he saw a burning boat and changed his direction. The next day he saw no trace of the mysterious vessel.

For some years after this, there was no light on Ram Island. Locals talked of ghosts that warned vessels away from the dangerous rocks. Robert Thayer Sterling, in his book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, tells several eerie stories of Ram Island.

One captain swore he was warned by a fog whistle at Ram Island during a snowstorm, which was impossible since there was no such signal there. Another fisherman was in danger of running into the rocks when he saw a burning boat and changed his direction. The next day he saw no trace of the mysterious vessel.

On another unusually dark night, a sailor was approaching Ram when he saw a woman in white waving a lighted torch over her head. The sailor veered off just in time to avoid being dashed on the rocks.

Circa 1900

Finally, a schooner helmsman claimed that a bolt of lightning illuminated the area moments before his vessel would have struck the ledges.

Congress finally appropriated $25,000 for a lighthouse in 1882. The light went into service on November 5, 1883. Soon after that, a severe hailstorm broke the lantern glass and the lamp was blown out by the wind. The keeper tried to keep the light going through the night by shielding it with newspapers.

The brick lighthouse, with a granite base, is very similar to the towers at Marshall Point and Isle au Haut. The tower was erected some yards offshore and a wooden walkway connected it to the island.

The 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses described a visit to Ram Island:

The keeper's house was near the top of the island. The lighthouse was some distance away, its heavy granite foundation on a level with the water, and washed constantly by the swell as it rolled in round the island, from the sea, -- for this lighthouse is not built upon the outer side of the island, but on the inner side, looking toward the shore, and is intended to light the entrance to Boothbay. As the keeper's house is some little distance above the shore, the connection between it and the lighthouse is made by a bridge, which joins the lighthouse about half-way up. The bridge is built of wood, resting on iron pillars securely mortised into the solid rock below, and gives a very easy mode of access to the lighthouse tower.

Congress finally appropriated $25,000 for a lighthouse in 1882. The light went into service on November 5, 1883. Soon after that, a severe hailstorm broke the lantern glass and the lamp was blown out by the wind. The keeper tried to keep the light going through the night by shielding it with newspapers.

The brick lighthouse, with a granite base, is very similar to the towers at Marshall Point and Isle au Haut. The tower was erected some yards offshore and a wooden walkway connected it to the island.

The 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses described a visit to Ram Island:

The keeper's house was near the top of the island. The lighthouse was some distance away, its heavy granite foundation on a level with the water, and washed constantly by the swell as it rolled in round the island, from the sea, -- for this lighthouse is not built upon the outer side of the island, but on the inner side, looking toward the shore, and is intended to light the entrance to Boothbay. As the keeper's house is some little distance above the shore, the connection between it and the lighthouse is made by a bridge, which joins the lighthouse about half-way up. The bridge is built of wood, resting on iron pillars securely mortised into the solid rock below, and gives a very easy mode of access to the lighthouse tower.

A Victorian keeper's house was also built in 1883. A fog bell, mounted on the side of the lighthouse tower, was added in 1897. In 1903 a vessel ran into the walkway to the lighthouse and destroyed it. It was soon rebuilt.

Circa 1930s

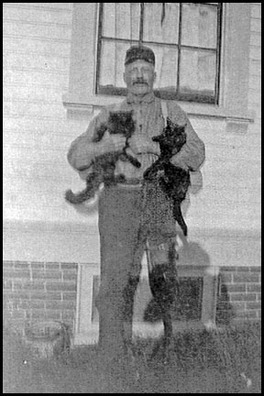

The first keeper was Samuel John Cavanor, a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia, who stayed at the light until he died in 1913. He lived on Ram Island with his wife, May, and their five daughters, who attended school in Boothbay. Cavanor had a wooden leg. He had been on the crew of a lighthouse tender, and a buoy raised by a derrick swung and crushed his leg. He had served as an assistant keeper at Seguin Island before going to Ram Island.

In an article written in 1900, William K. Larkin Jr., a lighthouse service machinist, recalled Cavanor as the most active keeper on the Maine coast, pegleg or not.

During Cavanor’s first winter on the island, a fierce hailstorm broke the lantern glass and briefly extinguished the light. Cavanor spent the rest of the night in the lantern, blocking the broken panes with newspapers and making sure the light stayed lit.

In an article written in 1900, William K. Larkin Jr., a lighthouse service machinist, recalled Cavanor as the most active keeper on the Maine coast, pegleg or not.

During Cavanor’s first winter on the island, a fierce hailstorm broke the lantern glass and briefly extinguished the light. Cavanor spent the rest of the night in the lantern, blocking the broken panes with newspapers and making sure the light stayed lit.

This was the first of many battles he waged with the elements; a storm carried away the station’s boat in February 1885, and the fog bell’s weight box was swept away by a storm in February 1898. The island’s three trees all blew down in a November 1900 gale.

Left: Keeper Samuel Cavanor with two of the light station’s resident cats, circa 1908. Courtesy of Gretchen LeBlanc and the Batty family.

Wrecks were still commonplace, despite the lighthouse. Cavanor recorded in his log in December 1884 that the schooner Mineola was a “totle rack” when it went ashore at Squirrel Island, about a mile to the west.

The schooner Garland was wrecked at the nearby rocks known as the Hypocrites in 1885, and hardly a year went by without at least one shipping disaster in the vicinity.

An account of a visit to Ram Island, written by Fred B. Babcock, was published in a magazine called The Cruiser :

The keeper, a sturdy old salt with one leg, invited us up to the house. We gladly accepted his kind invitation, as we were all pretty wet and cold. Once inside his warm kitchen all our troubles were forgotten as we listened to his stories of adventures on the sea. We were invited to dinner, and a most excellent one it was.

Wrecks were still commonplace, despite the lighthouse. Cavanor recorded in his log in December 1884 that the schooner Mineola was a “totle rack” when it went ashore at Squirrel Island, about a mile to the west.

The schooner Garland was wrecked at the nearby rocks known as the Hypocrites in 1885, and hardly a year went by without at least one shipping disaster in the vicinity.

An account of a visit to Ram Island, written by Fred B. Babcock, was published in a magazine called The Cruiser :

The keeper, a sturdy old salt with one leg, invited us up to the house. We gladly accepted his kind invitation, as we were all pretty wet and cold. Once inside his warm kitchen all our troubles were forgotten as we listened to his stories of adventures on the sea. We were invited to dinner, and a most excellent one it was.

Mary (May) Cavanor, Keeper Samuel Cavanor’s wife, is at the far left in this family portrait. Samuel is in the front center. Their youngest daughter, Wilhemina, is at the far right. Fred Batty is the second from the left, next to his future wife, Florence Cavanor. Grace, Florence’s twin sister, is next to Florence. Second from right is either Estelle or Margaret; the Cavanors’ fifth daughter may have been taking the photo. Fred Batty went on to become a lighthouse keeper at Maine’s Boon Island and Two Bush Island. Courtesy of Gretchen LeBlanc and the Batty family.

In late January 1903, during a heavy gale, the schooner Harriet W. Babson ran ashore at Ram Island, smashing through the walkway that connected the tower to the island.

Cavanor couldn’t access get to the lighthouse after the accident, so it remained dark for several nights until temporary repairs could be carried out. The walkway was eventually rebuilt.

Hospitality was an important part of the Cavanors’ island life. May Cavanor started a successful business serving fish dinners at a restaurant on Fisherman Island in 1904. When the Cavanors’ daughter Florence married Fred Batty on Thanksgiving Day in 1910, 65 lobsters were prepared for the assembled guests, along with turkey and fixings. Batty went on to serve as a lighthouse keeper at several Maine stations.

The Cavanors bought a house in Boothbay Harbor, and Samuel was planning to retire there because of heart trouble when he died suddenly in April 1913, eight days short of his sixty-second birthday. Keeper Dan Stevens of the Monhegan station was visiting with Cavanor, and he phoned the authorities with the bad news. A substitute keeper, O. G. Reed, was soon sent to the island. In an obituary in the Boothbay Register, Cavanor was described as a “big hearted, cheerful man” and a “friend to all in need.” According to the newspaper, “Probably no family in this vicinity were more attached to each other living all those years together on the little island.”

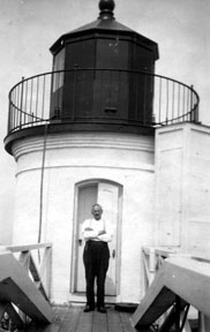

Left: Keeper Almon Mitchell at Ram Island Light. Courtesy of the Colby family.

Hospitality was an important part of the Cavanors’ island life. May Cavanor started a successful business serving fish dinners at a restaurant on Fisherman Island in 1904. When the Cavanors’ daughter Florence married Fred Batty on Thanksgiving Day in 1910, 65 lobsters were prepared for the assembled guests, along with turkey and fixings. Batty went on to serve as a lighthouse keeper at several Maine stations.

The Cavanors bought a house in Boothbay Harbor, and Samuel was planning to retire there because of heart trouble when he died suddenly in April 1913, eight days short of his sixty-second birthday. Keeper Dan Stevens of the Monhegan station was visiting with Cavanor, and he phoned the authorities with the bad news. A substitute keeper, O. G. Reed, was soon sent to the island. In an obituary in the Boothbay Register, Cavanor was described as a “big hearted, cheerful man” and a “friend to all in need.” According to the newspaper, “Probably no family in this vicinity were more attached to each other living all those years together on the little island.”

Left: Keeper Almon Mitchell at Ram Island Light. Courtesy of the Colby family.

Almon Mitchell was keeper from 1913 to 1925. He and his wife Emily Maria Mitchell had five children during their stay at Ram Island, between 1913 and 1923. Mitchell died on the island on May 4, 1925 at the age of 68.

Right: Keeper Almon Mitchell with his wife and five children at Ram Island Light. Courtesy of the Colby family.

Ram Island remained a family station in the Coast Guard era. Theresa Reece, wife of the Coast Guard officer in charge of the station, Wendell Reece, described life on Ram Island in a 1954 letter:

If we had all the modern conveniences, I would never want to leave Ram Island Light Station; as it is, we don't have any modern comforts, no electricty, no running water, no bathroom. We're living a primitive life. I miss all the comforts of home. I left them all to be with my husband. I'm looking forward to the day when we'll get a better light station, with all the comforts of home. Until that day comes, we'll make the best of it here.

The light was automated in 1965 and the Coast Guard keepers were removed. The station soon fell victim to vandals. The house was damaged, and in 1975 the fourth-order Fresnel lens was stolen. The lens was eventually recovered, and it's now at the museum of the Boothbay Region Historical Society.

Ram Island remained a family station in the Coast Guard era. Theresa Reece, wife of the Coast Guard officer in charge of the station, Wendell Reece, described life on Ram Island in a 1954 letter:

If we had all the modern conveniences, I would never want to leave Ram Island Light Station; as it is, we don't have any modern comforts, no electricty, no running water, no bathroom. We're living a primitive life. I miss all the comforts of home. I left them all to be with my husband. I'm looking forward to the day when we'll get a better light station, with all the comforts of home. Until that day comes, we'll make the best of it here.

The light was automated in 1965 and the Coast Guard keepers were removed. The station soon fell victim to vandals. The house was damaged, and in 1975 the fourth-order Fresnel lens was stolen. The lens was eventually recovered, and it's now at the museum of the Boothbay Region Historical Society.

In 1977, the Coast Guard repaired the lighthouse for $44,000 and removed the walkway, which had fallen into disrepair.

During this renovation, 14,000 bricks were replaced in the tower and the masonry base was repointed. The cast-iron lantern was removed and renovated.

The boathouse was destroyed in the great blizzard of February 6-7, 1978. The light station was offered to the town of Boothbay, but the high maintenance costs convinced town officials to decline the offer. In 1983, the keeper's house was slated to be destroyed when the Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust, associated with the Boothbay Railway Museum, stepped in and leased the station except for the tower. Under the Maine Lights Program, the property was transferred to the Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust in 1998.

Above: The new walkway, photo courtesy of Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust.

The boathouse was destroyed in the great blizzard of February 6-7, 1978. The light station was offered to the town of Boothbay, but the high maintenance costs convinced town officials to decline the offer. In 1983, the keeper's house was slated to be destroyed when the Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust, associated with the Boothbay Railway Museum, stepped in and leased the station except for the tower. Under the Maine Lights Program, the property was transferred to the Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust in 1998.

Above: The new walkway, photo courtesy of Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust.

The Ram Island Preservation Society, part of the Grand Banks Schooner Museum Trust, has restored the house. In late 2002, they reconstructed the walkway from the shore to the lighthouse tower.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Samuel John Cavanor (Cavenor) (1883-1913); O. G. Reed (1913); Almon Mitchell (1913-1925); Alonzo A. Conors (1925-?); C. N. Robinson (c. 1930s), Merrill Poor (1944); Clifton Morong (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); Ralph Norwood (Coast Guard, 1945-1950); Wendell Reece (Coast Guard, 1953-?)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Samuel John Cavanor (Cavenor) (1883-1913); O. G. Reed (1913); Almon Mitchell (1913-1925); Alonzo A. Conors (1925-?); C. N. Robinson (c. 1930s), Merrill Poor (1944); Clifton Morong (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); Ralph Norwood (Coast Guard, 1945-1950); Wendell Reece (Coast Guard, 1953-?)