History of Whale Rock Lighthouse, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Bibliography / Postcards

Whale Rock Light was constructed in 1882 to help mariners past a treacherous reef at the entrance to the busy West Passage of Narragansett Bay. Fifteen years before the lighthouse was built, a schooner had hit the rocks, killing five of the six men aboard.

A large ring was cut into the rock to prepare for the placement of a cast-iron caisson, which was then filled with concrete. The four-story lighthouse, equipped with a fog bell, was built on top of this cylinder. Three of the levels served as living quarters for the keepers.

Whale Rock was not a desirable location for keepers, and 16 different men served as head keeper between 1882 and 1909.

Judson Allen, after a few months as assistant, became principal keeper in September 1895. Henry Nygren arrived as assistant keeper during the following March. Articles in the New York Times and the Boston Globe described an incredible violent clash between the two men in August 1897. It was a drama Hollywood would be hard pressed to match.

Whale Rock was not a desirable location for keepers, and 16 different men served as head keeper between 1882 and 1909.

Judson Allen, after a few months as assistant, became principal keeper in September 1895. Henry Nygren arrived as assistant keeper during the following March. Articles in the New York Times and the Boston Globe described an incredible violent clash between the two men in August 1897. It was a drama Hollywood would be hard pressed to match.

It seems likely that this was only the latest battle in a war between Allen and Nygren that had been going on for a while. Things boiled to a heated peak on the evening of August 13. It isn’t clear how the fight started, but Nygren later claimed that Allen assaulted him first with a knife, causing two gashes in his forehead.

U.S. Coast Guard

The Globe account had Nygren grabbing Allen by the throat and being fought off with an oar, followed by the hurling of a bucket at Allen’s head. The Globe also claimed that Nygren had “filled up on liquor.”

Allen went up to the lantern to tend the light and turned around to see Nygren rushing at him with a knife. According to the Times, after Nygren slashed Allen’s coat, the two men ended up wrestling on the floor for possession of the weapon. Nygren was the bigger man, but Allen managed to kick the knife down the stairs.

As Nygren rushed down the stairs to regain the knife, Allen grabbed a rope and used it to make an escape over the side of the lighthouse. Nygren threatened to cut the rope, but Allen quickly reached the rocks below. As Allen pushed off onto the moonlit sea in a rowboat, Nygren appeared with a shotgun and fired two shots at the principal keeper.

His hands bleeding from his descent on the rope, Allen rowed for his life as the assistant hotly pursued him in a second boat. According to the Globe, Nygren continued to threaten Allen, yelling, “Oh, I’ll murder you! I’m after you!” Allen reached shore, commandeered a horse, and galloped to the next farmhouse he saw. Nygren abandoned pursuit and retreated to the lighthouse.

Two men from a local lifesaving station went out to the lighthouse on the following evening. They waited in the shadows while Nygren “smashed crockery, threw the utensils for housekeeping overboard and danced wildly,” according to the Globe. The men decided—understandably—not to risk entering the lighthouse. Nygren was finally apprehended and brought ashore in irons the next day. Officials of the Lighthouse Board soon dismissed him from government service.

According to a 1971 article by Richard L. Champlin in the journal of the Newport Historical Society, young Earl Caswell of Jamestown arrived fresh out of school in 1918 to spend a year as an assistant keeper. Caswell said he was told that it would be easy to stay out of trouble at such an isolated spot, but things weren’t that simple.

Caswell’s troubles began the day the head keeper’s daughter arrived while her father was painting the tower’s interior. The young woman and Caswell got into an argument, leading to the pitching of a tomato at Caswell’s head. Caswell dodged the juicy missile, but his boss wasn’t amused when it splatted against a freshly painted wall.

Caswell related many details of life at Whale Rock to Champlin. One of his duties was to crank up the clockwork mechanism that rang the fog bell; it would sound for four-and-a-half hours per winding. He bartered government paint for a lobster trap from a Portuguese lobsterman, but later got into trouble when another lobsterman reported his illegal trap.

Caswell recalled that the inside of the lighthouse was very cold in winter, despite the closed shutters on the windows. He also remembered photos of German vessels that were posted in the lighthouse in case of enemy attack, but wondered what good it would do if they had recognized such a vessel—there was no radio or telephone to communicate with anyone on shore.

During Caswell’s stay, the principal keeper told him that he felt the superstructure of the lighthouse was not adequately secured to the caisson. This observation would prove to be astute.

Allen went up to the lantern to tend the light and turned around to see Nygren rushing at him with a knife. According to the Times, after Nygren slashed Allen’s coat, the two men ended up wrestling on the floor for possession of the weapon. Nygren was the bigger man, but Allen managed to kick the knife down the stairs.

As Nygren rushed down the stairs to regain the knife, Allen grabbed a rope and used it to make an escape over the side of the lighthouse. Nygren threatened to cut the rope, but Allen quickly reached the rocks below. As Allen pushed off onto the moonlit sea in a rowboat, Nygren appeared with a shotgun and fired two shots at the principal keeper.

His hands bleeding from his descent on the rope, Allen rowed for his life as the assistant hotly pursued him in a second boat. According to the Globe, Nygren continued to threaten Allen, yelling, “Oh, I’ll murder you! I’m after you!” Allen reached shore, commandeered a horse, and galloped to the next farmhouse he saw. Nygren abandoned pursuit and retreated to the lighthouse.

Two men from a local lifesaving station went out to the lighthouse on the following evening. They waited in the shadows while Nygren “smashed crockery, threw the utensils for housekeeping overboard and danced wildly,” according to the Globe. The men decided—understandably—not to risk entering the lighthouse. Nygren was finally apprehended and brought ashore in irons the next day. Officials of the Lighthouse Board soon dismissed him from government service.

According to a 1971 article by Richard L. Champlin in the journal of the Newport Historical Society, young Earl Caswell of Jamestown arrived fresh out of school in 1918 to spend a year as an assistant keeper. Caswell said he was told that it would be easy to stay out of trouble at such an isolated spot, but things weren’t that simple.

Caswell’s troubles began the day the head keeper’s daughter arrived while her father was painting the tower’s interior. The young woman and Caswell got into an argument, leading to the pitching of a tomato at Caswell’s head. Caswell dodged the juicy missile, but his boss wasn’t amused when it splatted against a freshly painted wall.

Caswell related many details of life at Whale Rock to Champlin. One of his duties was to crank up the clockwork mechanism that rang the fog bell; it would sound for four-and-a-half hours per winding. He bartered government paint for a lobster trap from a Portuguese lobsterman, but later got into trouble when another lobsterman reported his illegal trap.

Caswell recalled that the inside of the lighthouse was very cold in winter, despite the closed shutters on the windows. He also remembered photos of German vessels that were posted in the lighthouse in case of enemy attack, but wondered what good it would do if they had recognized such a vessel—there was no radio or telephone to communicate with anyone on shore.

During Caswell’s stay, the principal keeper told him that he felt the superstructure of the lighthouse was not adequately secured to the caisson. This observation would prove to be astute.

Whale Rock was assigned two assistant keepers beginning in the early 1920s. Walter Barge Eberle, father of six children, became the second assistant in 1937.

Eberle was a 20-year veteran of the U.S. Navy. Born in Webster City, Iowa, in 1898, he had run away from home and lied about his age when he enlisted in the navy at age 15.

Later, Eberle worked for a time at a Wrigley chewing gum factory in Newport. He had spent some of his Navy time in the area, serving on submarines and diving for dud torpedoes around Goat Island in Newport Harbor.

“The ocean was his life,” said Eberle’s daughter, Barbara Bramwell, in a July 2000 interview. Her sister, Dorothy Roach, added, “He always said he would die in the ocean.”

Left: Walter B. Eberle and his wife Agnes in happier times. Courtesy of the family of Walter Eberle.

Later, Eberle worked for a time at a Wrigley chewing gum factory in Newport. He had spent some of his Navy time in the area, serving on submarines and diving for dud torpedoes around Goat Island in Newport Harbor.

“The ocean was his life,” said Eberle’s daughter, Barbara Bramwell, in a July 2000 interview. Her sister, Dorothy Roach, added, “He always said he would die in the ocean.”

Left: Walter B. Eberle and his wife Agnes in happier times. Courtesy of the family of Walter Eberle.

Eberle, missing the sea, entered the lighthouse service in 1937 and was assigned to Whale Rock, a welcome assignment since it was relatively close to the family’s home in Newport. Eberle sometimes brought his eldest son, Walter, Jr., to the station.

Eberle’s daughter, Dorothy Roach, later recalled that her father suspected the approach of foul weather on September 21, 1938. Knowing how tough it was to land and secure the boat at the lighthouse in rough seas, he left the mainland earlier than had been scheduled to relieve Keeper Dan Sullivan at the lighthouse. The other assistant, Gustav Larson, was away on vacation.

With no advance warning, a devastating hurricane was bearing down on New England’s south-facing coast. The waves grew higher and higher. Eberle’s daughter, Dorothy, was 12 years old in 1938. By mid-afternoon, when she got out of school, trees were falling in the high winds. Arriving home, Dorothy was told that her mother had gone to see the thundering surf that could be heard from their home.

Dorothy went toward Easton Beach in Newport to look for her mother, Agnes Eberle. As she looked down at the beach and boardwalk arcade, she was horrified to see an enormous tidal wave sweep over the area. The arcade was suddenly gone, along with the children that she believed were inside. Dorothy and her mother were soon reunited with the rest of the family at their home.

Right: Wedding photo of Agnes and Walter Eberle. Courtesy of the Eberle family.

With no advance warning, a devastating hurricane was bearing down on New England’s south-facing coast. The waves grew higher and higher. Eberle’s daughter, Dorothy, was 12 years old in 1938. By mid-afternoon, when she got out of school, trees were falling in the high winds. Arriving home, Dorothy was told that her mother had gone to see the thundering surf that could be heard from their home.

Dorothy went toward Easton Beach in Newport to look for her mother, Agnes Eberle. As she looked down at the beach and boardwalk arcade, she was horrified to see an enormous tidal wave sweep over the area. The arcade was suddenly gone, along with the children that she believed were inside. Dorothy and her mother were soon reunited with the rest of the family at their home.

Right: Wedding photo of Agnes and Walter Eberle. Courtesy of the Eberle family.

It was a long, anxious night for the Eberles. At about 5:30 in the morning, Keeper Sullivan phoned the family.

His words were simple and to the point: “The light is gone.” Many days passed before the seas calmed down enough to get a boat out to Whale Rock. The lighthouse and 40-year-old Walter Eberle were gone. Eberle was 40 years old and had been in the Lighthouse Service for one year.

More than 700 people died in the hurricane across New England, including five people at the lighthouse station on Rhode Island's Prudence Island.

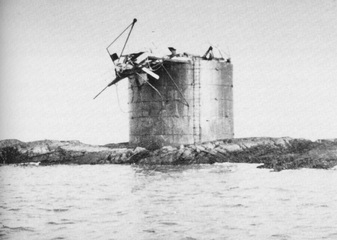

According to a report by the Commissioner of Lighthouses, the caisson and entrance ladder were found still intact, and the landing platform was still in place but badly twisted. The basement and entry-level concrete deck were also still intact.

More than 700 people died in the hurricane across New England, including five people at the lighthouse station on Rhode Island's Prudence Island.

According to a report by the Commissioner of Lighthouses, the caisson and entrance ladder were found still intact, and the landing platform was still in place but badly twisted. The basement and entry-level concrete deck were also still intact.

The investigation revealed that there was “no evidence of anchor bolts or any other means by which the cast iron tower plates were actually held to the masonry pier, except for the brick tower lining.”

While startling, this defect doesn’t seem to have directly contributed to the demise of the lighthouse. Examination of some of the iron plates from the superstructure showed that many of the flange bolts holding them together had either sheared off or pulled through. Much of the wreckage that was found on the base was directly below its original position, and some of the keepers’ belongings, including books and clothing, were found in relatively good condition except for being soaked.

The report concluded:

From these findings it would appear that the top two stories, watch room and lantern, broke loose from the lower two stories and went overboard. Most keepers at other similar stations who were on duty during the storm stated that they took refuge in the top story. . . . The deceased keeper of Whale Rock was undoubtedly in the same place when the top portion of the tower went. . . . With the top gone and brick lining weakened, the remaining two floors dropped down, probably, distorting the shell plates sufficiently to collapse them.

An automatic light on a steel tower was soon erected, with a flashing green light 59 feet above the water. A buoy now marks the spot.

The remains of the structure were removed in 1939 and an automatic light on a steel tower was erected. That light is now gone.

You can view what's left of the base of Whale Rock Light from the area around Beavertail Lighthouse. During their lighthouse cruises (May - October), Rhode Island Bay Cruises passes near the ruins of the base.

The report concluded:

From these findings it would appear that the top two stories, watch room and lantern, broke loose from the lower two stories and went overboard. Most keepers at other similar stations who were on duty during the storm stated that they took refuge in the top story. . . . The deceased keeper of Whale Rock was undoubtedly in the same place when the top portion of the tower went. . . . With the top gone and brick lining weakened, the remaining two floors dropped down, probably, distorting the shell plates sufficiently to collapse them.

An automatic light on a steel tower was soon erected, with a flashing green light 59 feet above the water. A buoy now marks the spot.

The remains of the structure were removed in 1939 and an automatic light on a steel tower was erected. That light is now gone.

You can view what's left of the base of Whale Rock Light from the area around Beavertail Lighthouse. During their lighthouse cruises (May - October), Rhode Island Bay Cruises passes near the ruins of the base.

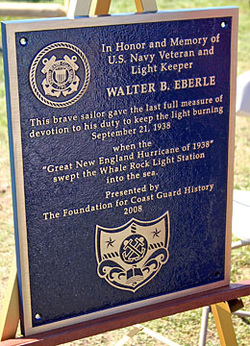

On September 21, 2008, a plaque (below) was dedicated in memory of Walter Barge Eberle, thanks to the efforts of David S. Robinson of the Friends of Whale Rock Light, along with the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum and the Foundation for Coast Guard History. The plaque is on display at the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum in Jamestown, Rhode Island.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Nathaniel S. Dodge (1882-1885), John W. Dodge (1st Assistant, 1882-1884), Elam P. Littlefield (1st Assistant 1884-1885, Keeper 1885-1891), Joseph B. Eddy (1st Assistant 1886), Charles Wright (1st Assistant 1886-1887), Eugene R. Milliken (1st Assistant 1887-1888), William Roman (1st Assistant 1888-1890), Edward Andrews (1st Assistant 1890-1891, Keeper 1891-1893), Henricus DeVries (1st Assistant 1891), Nelson Sprague (1st Assistant 1891-1892 and 1900, Keeper 1900-1901), Herbert R. Kenyon (1st Assistant 1892), Charles E. Smith (1st Assistant 1892-1893, Keeper 1893-1895), Frank Tardiff (1st Assistant 1893-1894), Sylvester Allen (1st Assistant 1894-1895, Keeper 1895), Judson G. Allen (1895), Isaac G. Hoard, (1st Assistant 1895-1896), Henry Nygren (1st Assistant 1896-1897), Joshua A. Overton (1st Assistant 1897-1899, Keeper 1899-1900), Charles W. Oliver (1st Assistant 1897-1899), John G. Skipworth (1st Assistant 1898-1899), B. A. Francisco (1st Assistant 1898-1899), Silas E. Stanton (Staton?) (assistant 1900-1901, Keeper 1901), Joseph D. Meade (1901-1902), Peter M. Peterson (1902-1908), Marten W. Ekman (1st Assistant 1901-1902), Willis A. Green (1st Assistant 1902-1903), Morell E. Hulse (1st Assistant 1903-1905), Edward R. Curtis (1st Assistant 1905-1906), John A. Burke (1st Assistant 1906), Ernest Bloom (1st Assistant 1906-1908), Haus. Anderson (1st Assistant 1908, Keeper 1908-1910), John S, Sheridan (1910), John C. W. Porter (1910-1912), Theodore De Shong (1911-1913), William F. Aichels (1908), Robert G. Lamer (1st Assistant 1911), J. O. Browley (Joseph O. Bouley ?) (1st Assistant 1911-1914), Simon Sivounich (1st Assistant 1908-1911), Robert G. Lamer (1st Assistant 1908-1911), Hans C. Anderson (1908-1911), John (Jack) Larsen (1914-1915), Arthur E. Larkin (1st Assistant 1914-1915), Edward Grime (1915-1916), Otis L. Barstow (1st Assistant 1915-1916, Keeper 1916-1918), George H. Tooker (1st Assistant 1916-1918, Keeper 1918-1925), George T. Gardiner (1st Assistant 1921-1925), George A. Scheer (2nd Assistant 1921-1923), Thomas H. Winn (2nd Assistant 1923-1925), Fred B. White (1925-1927), Daniel A. Sullivan (1st Assistant 1925-1927, Keeper 1927-1938), Alfred Auger (2nd Assistant 1925-1927), Willam O. Chapel (1st Assistant 1927-1931), Robert H. Lyons (2nd Assistant 1927-1929), Joseph G. Hindley (2nd Assistant 1929-1931, 1st Assistant 1931), Harold E. Davis (2nd Assistant 1931), Peter Roudeau (1st Assistant 1931-1937), Ernest Stacey (2nd Assistant, Feb. 12, 1931 - Feb. 12, 1937), Joseph H. Dubois (1st Assistant,1937-1938), Octavius E. Davis (first assistant, c. 1938); Gustav H. Larson (assistant, 1938); Walter Eberle (2nd Assistant, 1937-1938, died in service).

Nathaniel S. Dodge (1882-1885), John W. Dodge (1st Assistant, 1882-1884), Elam P. Littlefield (1st Assistant 1884-1885, Keeper 1885-1891), Joseph B. Eddy (1st Assistant 1886), Charles Wright (1st Assistant 1886-1887), Eugene R. Milliken (1st Assistant 1887-1888), William Roman (1st Assistant 1888-1890), Edward Andrews (1st Assistant 1890-1891, Keeper 1891-1893), Henricus DeVries (1st Assistant 1891), Nelson Sprague (1st Assistant 1891-1892 and 1900, Keeper 1900-1901), Herbert R. Kenyon (1st Assistant 1892), Charles E. Smith (1st Assistant 1892-1893, Keeper 1893-1895), Frank Tardiff (1st Assistant 1893-1894), Sylvester Allen (1st Assistant 1894-1895, Keeper 1895), Judson G. Allen (1895), Isaac G. Hoard, (1st Assistant 1895-1896), Henry Nygren (1st Assistant 1896-1897), Joshua A. Overton (1st Assistant 1897-1899, Keeper 1899-1900), Charles W. Oliver (1st Assistant 1897-1899), John G. Skipworth (1st Assistant 1898-1899), B. A. Francisco (1st Assistant 1898-1899), Silas E. Stanton (Staton?) (assistant 1900-1901, Keeper 1901), Joseph D. Meade (1901-1902), Peter M. Peterson (1902-1908), Marten W. Ekman (1st Assistant 1901-1902), Willis A. Green (1st Assistant 1902-1903), Morell E. Hulse (1st Assistant 1903-1905), Edward R. Curtis (1st Assistant 1905-1906), John A. Burke (1st Assistant 1906), Ernest Bloom (1st Assistant 1906-1908), Haus. Anderson (1st Assistant 1908, Keeper 1908-1910), John S, Sheridan (1910), John C. W. Porter (1910-1912), Theodore De Shong (1911-1913), William F. Aichels (1908), Robert G. Lamer (1st Assistant 1911), J. O. Browley (Joseph O. Bouley ?) (1st Assistant 1911-1914), Simon Sivounich (1st Assistant 1908-1911), Robert G. Lamer (1st Assistant 1908-1911), Hans C. Anderson (1908-1911), John (Jack) Larsen (1914-1915), Arthur E. Larkin (1st Assistant 1914-1915), Edward Grime (1915-1916), Otis L. Barstow (1st Assistant 1915-1916, Keeper 1916-1918), George H. Tooker (1st Assistant 1916-1918, Keeper 1918-1925), George T. Gardiner (1st Assistant 1921-1925), George A. Scheer (2nd Assistant 1921-1923), Thomas H. Winn (2nd Assistant 1923-1925), Fred B. White (1925-1927), Daniel A. Sullivan (1st Assistant 1925-1927, Keeper 1927-1938), Alfred Auger (2nd Assistant 1925-1927), Willam O. Chapel (1st Assistant 1927-1931), Robert H. Lyons (2nd Assistant 1927-1929), Joseph G. Hindley (2nd Assistant 1929-1931, 1st Assistant 1931), Harold E. Davis (2nd Assistant 1931), Peter Roudeau (1st Assistant 1931-1937), Ernest Stacey (2nd Assistant, Feb. 12, 1931 - Feb. 12, 1937), Joseph H. Dubois (1st Assistant,1937-1938), Octavius E. Davis (first assistant, c. 1938); Gustav H. Larson (assistant, 1938); Walter Eberle (2nd Assistant, 1937-1938, died in service).