History of Lubec Channel Light, Lubec, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

In the late 1800s, Lubec, the most northeasterly town in the United States, was an important trade and fishing port. The town later became a center of the sardine industry; it was home to 20 packing plants.

U.S. Coast Guard

The slender channel called Lubec Narrows, between Lubec and Campobello Island, New Brunswick, was dredged in the early 1880s. The Lighthouse Board urged the funding of a lighthouse at the entrance to Lubec Narrows, which would make the channel “of value to commerce at night.” Congress appropriated $40,000 for a lighthouse in the summer of 1886.

Title to the lighthouse site was secured from the State of Maine, and borings were made in 1887 into the “tough blue clay” at the shoal. As the project progressed, it became apparent that additional funds were needed. Congress appropriated $12,000 more in 1888, and during the following year three contracts were made: one for the metalwork from Detroit, Michigan, one for Portland cement from Boston, and one for the construction of the lighthouse.

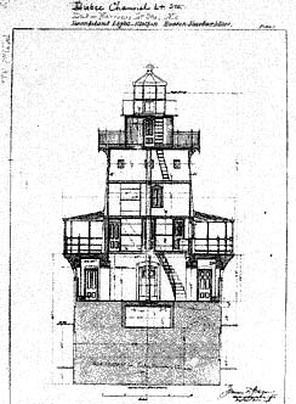

The 1890 annual report of the Lighthouse Board provides a detailed description of the lighthouse and its construction in 1889:

The lighthouse which is now being built is to consist of a cylindrical iron caisson, 33 feet in diameter and 48 feet high, cast in eight sections of thirty-two plates each . . . to be sunk 6 feet into the site (11 feet below extreme low and 36 feet below extreme high water), filled with concrete, and surmounted by an iron tower, 37 feet in height from base to focal plane. . . .

Title to the lighthouse site was secured from the State of Maine, and borings were made in 1887 into the “tough blue clay” at the shoal. As the project progressed, it became apparent that additional funds were needed. Congress appropriated $12,000 more in 1888, and during the following year three contracts were made: one for the metalwork from Detroit, Michigan, one for Portland cement from Boston, and one for the construction of the lighthouse.

The 1890 annual report of the Lighthouse Board provides a detailed description of the lighthouse and its construction in 1889:

The lighthouse which is now being built is to consist of a cylindrical iron caisson, 33 feet in diameter and 48 feet high, cast in eight sections of thirty-two plates each . . . to be sunk 6 feet into the site (11 feet below extreme low and 36 feet below extreme high water), filled with concrete, and surmounted by an iron tower, 37 feet in height from base to focal plane. . . .

Advantage was taken of the great range, 17 to 21 feet, of the tides to erect the two lower sections of the caisson on the mud flats in the vicinity, whence they were very readily floated, by temporary caisson, to the site, and there sunk. After carrying up the caisson to the height of 36 feet, by the addition of four more sections, it was pumped out and sunk by excavation to the depth of four feet, when an irruption of water through the subsoil, on August 29, 1889, within the caisson, interrupted the work and made necessary a sub-foundation of piles.

Work resumed the following April and the subfoundation was completed in June. It consisted of 185 spruce piles driven within the cylinder. Twenty-three of the piles, forming a ring around the perimeter of the cylinder, were driven to a depth of 69 feet, and the 162 interior piles were driven 35 to 45 feet into the bottom. The cylinder was sunk to a depth of six feet and leveled, and then filled with concrete.

After a final appropriation of $15,500, work was completed by the end of 1890. The lighthouse superstructure was completed by November 5, and a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the lantern. A 1,200-pound fog bell, struck by machinery, was also installed.

The station went into operation on December 31, 1890, with a white flash every 15 seconds shown from 61 feet above sea level. The tower was painted brown until 1903, when it was changed to white.

Lubec Channel Light was a "stag" station staffed by two male keepers. The first principal keeper was Frederick W. Morong and the assistant was Loring W. Myers.

There were once miniature brass lighthouses on each baluster on the lighthouse's gallery. These rare decorations have been removed. The tower contained five levels, two of which were living quarters for the keepers. The lower deck was a combination living room and kitchen. The next deck was a bedroom.

After a final appropriation of $15,500, work was completed by the end of 1890. The lighthouse superstructure was completed by November 5, and a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed in the lantern. A 1,200-pound fog bell, struck by machinery, was also installed.

The station went into operation on December 31, 1890, with a white flash every 15 seconds shown from 61 feet above sea level. The tower was painted brown until 1903, when it was changed to white.

Lubec Channel Light was a "stag" station staffed by two male keepers. The first principal keeper was Frederick W. Morong and the assistant was Loring W. Myers.

There were once miniature brass lighthouses on each baluster on the lighthouse's gallery. These rare decorations have been removed. The tower contained five levels, two of which were living quarters for the keepers. The lower deck was a combination living room and kitchen. The next deck was a bedroom.

Loring W. Myers, formerly a steamboat captain, advanced to principal keeper in 1898 and was in charge until 1923. Before he became a lighthouse keeper, Myers had lost his first wife and three children to illness. He later remarried. Myers moonlighted as an entrepreneur and inventor; he dabbled in real estate and owned a sardine packing plant.

Circa 1900

In 1904, Myers was credited with the invention of a new type of lifeboat, described as “buoyant as a cork” and watertight. The craft, 16 feet long and 7 feet wide, was constructed of oak planks covered with galvanized steel inside and out. Loaded with 15 men, the boat was only two or three inches lower in the water than when it was empty.

Myers’ invention was roundly praised, but it never made Myers any money, as steamship lines preferred to keep using less expensive, and less safe, lifeboats.

In the spring of 1899, the assistant keeper, Herbert Robinson, had to spend an extended period on the mainland, through the sickness and eventual death of his son. During some of this time, Myers’s wife, Abbie, served as the assistant—the only woman keeper in the station’s history.

Myers was credited with many lives saved during his long career. Once, a group of young women was passing by in a motor vessel when the boat caught fire. Myers rushed to the scene and rescued all the women, who were described as hysterical.

On another occasion, the keeper saved two men whose boat had capsized near the shore of Campobello. The men were clinging to fishing weir stakes when Myers reached them.

Myers’ invention was roundly praised, but it never made Myers any money, as steamship lines preferred to keep using less expensive, and less safe, lifeboats.

In the spring of 1899, the assistant keeper, Herbert Robinson, had to spend an extended period on the mainland, through the sickness and eventual death of his son. During some of this time, Myers’s wife, Abbie, served as the assistant—the only woman keeper in the station’s history.

Myers was credited with many lives saved during his long career. Once, a group of young women was passing by in a motor vessel when the boat caught fire. Myers rushed to the scene and rescued all the women, who were described as hysterical.

On another occasion, the keeper saved two men whose boat had capsized near the shore of Campobello. The men were clinging to fishing weir stakes when Myers reached them.

Elson Small, who went on to a 28-year career at several stations, became the assistant keeper in November 1920, weeks before he married Loring Myers’s niece, Constance “Connie” Scovill. Myers and Small alternated two-day stays at the lighthouse.

Elson Small

When 19-year-old Connie went with her husband to visit the lighthouse for the first time, she was intimidated by the idea of climbing the 30-foot ladder. In her book, The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife, she later wrote:

I had been afraid of boats and the sea since a cousin teasingly rocked a rowboat we were in when I was three years old. I never learned to row until after I married Elson. I was also afraid of heights, but trying not to show just how scared I was, I said to Elson, “I can never climb up there."

"Oh yes, you can. Just grab the rungs and I’ll be right behind you.”

So, with him behind me telling me to look up and never down, I made it. To this day I have kept his words with me and when I’d get discouraged I would think of them. They’ve helped me a good many times to overcome a panicky feeling and do what had to be done.

I had been afraid of boats and the sea since a cousin teasingly rocked a rowboat we were in when I was three years old. I never learned to row until after I married Elson. I was also afraid of heights, but trying not to show just how scared I was, I said to Elson, “I can never climb up there."

"Oh yes, you can. Just grab the rungs and I’ll be right behind you.”

So, with him behind me telling me to look up and never down, I made it. To this day I have kept his words with me and when I’d get discouraged I would think of them. They’ve helped me a good many times to overcome a panicky feeling and do what had to be done.

Keeper Nathaniel Alley was alone on duty on March 7, 1934, when he was overcome by fumes from the coal stove.

The captain of the Grand Manan ferry, which ran regularly through the area, was accustomed to hailing the man on duty. When no one appeared, the captain became suspicious. Alley was found and taken to Lubec for medical treatment, but he soon died.

The light was automated in 1939, with the installation of an acetylene gas system and a sun valve.

In 1989 the light was to be discontinued, but local residents mounted a "Save the Sparkplug" campaign. Automobile sparkplugs were handed out to gain attention for the cause. In 1992, a $700,000 renovation restored Lubec Channel Light to its best condition in decades. The renovation included the stabilization of the foundation, which had developed a tilt over the years. New plates were installed on the caisson and 200 cubic yards of concrete was pumped in.

Twelve piles were then driven through the caisson into the bedrock. One of the piles was driven 149 feet. The lighthouse still has a six-degree list but is considered stable.

In the summer of 2001, the lighthouse received a new coat of paint and other maintenance from the U.S. Coast Guard. The crew out of Southwest Harbor, Maine, spent four days working on the tower. In her honor, the Coast Guard crew painted "Connie Small was here" on the tower.

Lubec is still an active fishing community and the Channel Light remains an important aid to navigation. The lighthouse can easily be seen from many points on shore. When visiting the area be sure to drive to Campobello Island, site of Franklin D. Roosevelt's former summer home and East Quoddy Head Lighthouse. Also, you might want to stop at the Lubec Historical Society to see a 1,000-pound fog bell once used at Lubec Channel Light.

In 2006, the lighthouse was made available to a suitable new steward under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. There were no applicants, so in July 2007 it was auctioned to Gary Zaremba for a high bid of $46,000. You can read more about him here.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Frederick W. Morong (1890-1898); Loring W. Myers (assistant, 1890-1898, principal keeper 1898-circa 1923), Almon Mitchell (assistant, c. 1902-1905), Elson Small (assistant, 1920-1922), Ernest William Moores (?), ? Park (?), Parker M. Hoghton (c. 1926), ? Robinson (?), James Doran (?), Everett E. Moore (1929), Arthur Robie Marston (c. 1935), Nathaniel Alley (assistant, 1924-1929, principal keeper 1929-1934), Earle B. Ashby (1934-1939)

The light was automated in 1939, with the installation of an acetylene gas system and a sun valve.

In 1989 the light was to be discontinued, but local residents mounted a "Save the Sparkplug" campaign. Automobile sparkplugs were handed out to gain attention for the cause. In 1992, a $700,000 renovation restored Lubec Channel Light to its best condition in decades. The renovation included the stabilization of the foundation, which had developed a tilt over the years. New plates were installed on the caisson and 200 cubic yards of concrete was pumped in.

Twelve piles were then driven through the caisson into the bedrock. One of the piles was driven 149 feet. The lighthouse still has a six-degree list but is considered stable.

In the summer of 2001, the lighthouse received a new coat of paint and other maintenance from the U.S. Coast Guard. The crew out of Southwest Harbor, Maine, spent four days working on the tower. In her honor, the Coast Guard crew painted "Connie Small was here" on the tower.

Lubec is still an active fishing community and the Channel Light remains an important aid to navigation. The lighthouse can easily be seen from many points on shore. When visiting the area be sure to drive to Campobello Island, site of Franklin D. Roosevelt's former summer home and East Quoddy Head Lighthouse. Also, you might want to stop at the Lubec Historical Society to see a 1,000-pound fog bell once used at Lubec Channel Light.

In 2006, the lighthouse was made available to a suitable new steward under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. There were no applicants, so in July 2007 it was auctioned to Gary Zaremba for a high bid of $46,000. You can read more about him here.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Frederick W. Morong (1890-1898); Loring W. Myers (assistant, 1890-1898, principal keeper 1898-circa 1923), Almon Mitchell (assistant, c. 1902-1905), Elson Small (assistant, 1920-1922), Ernest William Moores (?), ? Park (?), Parker M. Hoghton (c. 1926), ? Robinson (?), James Doran (?), Everett E. Moore (1929), Arthur Robie Marston (c. 1935), Nathaniel Alley (assistant, 1924-1929, principal keeper 1929-1934), Earle B. Ashby (1934-1939)