History of Matinicus Rock Light, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Click here for a gallery of Matinicus Rock Light photos on SmugMug (prints and gift items available)

There is neither tree nor shrub, and hardly a blade of grass on the rock. The surface is rough and irregular and resembles a confused pile of loose stone. Portions of the rock are frequently swept over by waves which move the huge boulders into new positions. -- 1891 Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board.

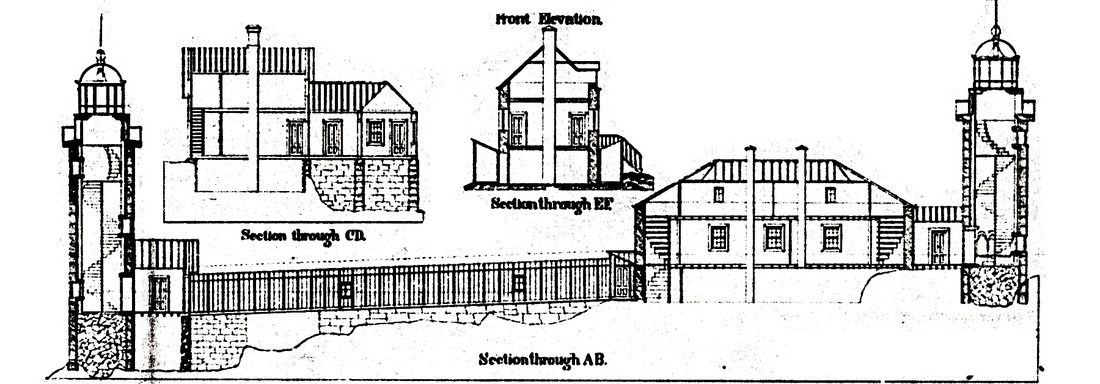

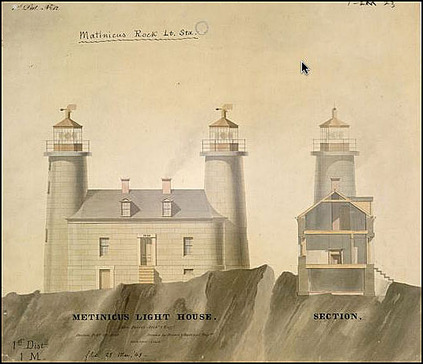

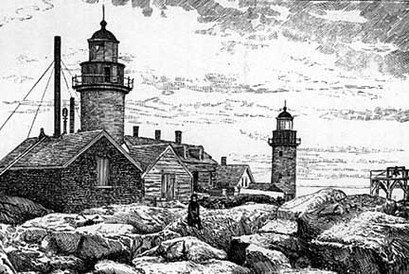

1848 illustration of Matinicus Rock Light Station. National Archives.

Matinicus Rock is a windswept 32-acre granite island, 18 miles off the mainland and 25 miles from Rockland, the nearest port. "The Rock" is five miles south of the much larger Matinicus Island. It was recorded by Capt. John Smith in 1614, who made notes in his log about "the rock of Mattinack."

Because of its prominent location on the approach to busy Penobscot Bay, Congress and President John Quincy Adams authorized the building of two lighthouses on Matinicus Rock in 1827. It was considered a primary seacoast light station.

The first lighthouse building was a stone dwelling with a wooden tower at each end, 40 feet apart. Each tower exhibited a fixed white light. The first keeper, 65-year-old John A. Shaw, was appointed at a yearly salary of $450. Shaw and his wife lived at the station until 1831, when Shaw became too ill to continue as keeper. He subsequently died in a Portland hospital. The second keeper, Phineas Spear, also died after a short time at the Rock. The cold, damp air and frequent storms no doubt contributed to the keepers' illnesses.

A tremendous storm in January 1839 did much damage to the buildings and put the lights out of operation. Two days later, the keeper was able to hang a temporary lamp from a mast. The station was soon repaired. Two months after the great storm, Samuel Abbott was appointed keeper at $450 yearly.

Because of its prominent location on the approach to busy Penobscot Bay, Congress and President John Quincy Adams authorized the building of two lighthouses on Matinicus Rock in 1827. It was considered a primary seacoast light station.

The first lighthouse building was a stone dwelling with a wooden tower at each end, 40 feet apart. Each tower exhibited a fixed white light. The first keeper, 65-year-old John A. Shaw, was appointed at a yearly salary of $450. Shaw and his wife lived at the station until 1831, when Shaw became too ill to continue as keeper. He subsequently died in a Portland hospital. The second keeper, Phineas Spear, also died after a short time at the Rock. The cold, damp air and frequent storms no doubt contributed to the keepers' illnesses.

A tremendous storm in January 1839 did much damage to the buildings and put the lights out of operation. Two days later, the keeper was able to hang a temporary lamp from a mast. The station was soon repaired. Two months after the great storm, Samuel Abbott was appointed keeper at $450 yearly.

In February 1842, Abbott and his family were forced to take refuge in the attic of the dwelling during another storm that produced unusually high seas. The kitchen wing of the house was practically demolished by the waves and the first floor was filled waist-deep with water. "Had not a sudden shift of wind ensued," Abbott reported, "I believe another shock would have entirely destroyed the building."

From "Matinicus Isle: Its Story and its People," by Charles A. E. Long, 1926.

A new granite dwelling, designed by Alexander Parris, was built by the contractor Gridley Bryant at a cost of $10,250 in 1846. The stone towers built at each end of the dwelling were just slightly farther apart than the old ones, in spite of complaints that the lights sometimes blended into a single light from certain directions. The new lights were higher than the old ones—90 and 85 feet above mean high water. The old wooden towers were torn down, but the first dwelling remained and was used as a storage shed.

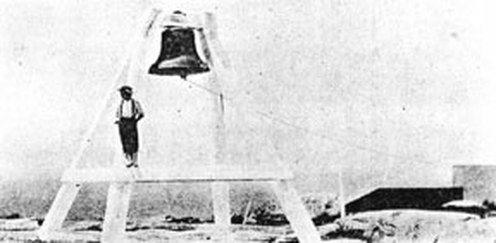

Because Matinicus Rock was frequently enshrouded in fog, a 2,000-pound fog bell was added in 1856. The bell is now at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland, Maine.

A new bell tower with striking machinery was installed in 1867. In 1869, a steam-driven fog whistle -- one of the first used anywhere -- was installed. The bell was retained as a backup signal.

Because Matinicus Rock was frequently enshrouded in fog, a 2,000-pound fog bell was added in 1856. The bell is now at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland, Maine.

A new bell tower with striking machinery was installed in 1867. In 1869, a steam-driven fog whistle -- one of the first used anywhere -- was installed. The bell was retained as a backup signal.

Samuel Burgess became keeper in 1853. Burgess and his invalid wife, Thankful (Phinney) moved to the station with several of their ten children; their oldest daughters had already married. Their oldest son, Benjamin, soon left to earn a living as a fisherman. The Burgess's oldest daughter living at the light station, Abbie, had been born on Matinicus Island in August 1839. She quickly learned to light the whale oil lamps and perform other duties around the Rock.

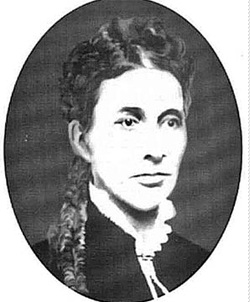

19th century illustration of Abbie Burgess

In January 1856, Burgess left in his sailboat to pick up supplies, leaving Abbie alone with her mother and younger sisters. "I can depend on you, Abbie," he said as he left the island.

By the afternoon a storm began to approach Penobscot Bay. Soon the waves grew large as the wind increased, and the gale continued to worsen over the next three days. On January 19, Matinicus Rock was practically underwater. Abbie moved her mother and sisters to the north lighthouse tower. She later wrote:

The new dwelling was flooded and the windows had to be secured to prevent the violence of the spray from breaking them in. As the tide came, the sea rose higher and higher, till the only endurable places were the light-towers. If they stood we were saved, otherwise our fate was only too certain. But for some reason, I know not why, I had no misgivings, and went on with my work as usual. For four weeks, owing to rough weather, no landing could be effected on the Rock. During this time we were without the assistance of any male member of our family. Though at times greatly exhausted with my labors, not once did the lights fail. Under God I was able to perform all my accustomed duties as well as my father's.

By the afternoon a storm began to approach Penobscot Bay. Soon the waves grew large as the wind increased, and the gale continued to worsen over the next three days. On January 19, Matinicus Rock was practically underwater. Abbie moved her mother and sisters to the north lighthouse tower. She later wrote:

The new dwelling was flooded and the windows had to be secured to prevent the violence of the spray from breaking them in. As the tide came, the sea rose higher and higher, till the only endurable places were the light-towers. If they stood we were saved, otherwise our fate was only too certain. But for some reason, I know not why, I had no misgivings, and went on with my work as usual. For four weeks, owing to rough weather, no landing could be effected on the Rock. During this time we were without the assistance of any male member of our family. Though at times greatly exhausted with my labors, not once did the lights fail. Under God I was able to perform all my accustomed duties as well as my father's.

Abbie waded knee-deep in the water to rescue her pet chickens from their coop. A short time later a gigantic wave swept the island and destroyed the original keeper's house.

Abbie Burgess (U.S. Coast Guard)

The rough seas abated somewhat, but it remained impossible to land at the Rock for four weeks. During this time Abbie kept the lights burning and cared for her mother and sisters.

Samuel Burgess finally made it back to the Rock, happy to find his family alive and well. Again in 1857 he was away for three weeks during a stormy period. This time the family's food supply was reduced to one egg and a cup of corn meal mush a day before supplies arrived.

Samuel Burgess lost his job in 1861 for political reasons. Capt. John Grant, a friend of the Burgess family, became the next keeper. Abbie stayed on to help train Grant. The new keeper's son, Isaac, was the assistant keeper.

A romance quickly developed between Abbie Burgess and Isaac Grant, and they were married within a year. Abbie was officially appointed assistant keeper at $440 per year. The couple had four children at the Rock before Isaac Grant's appointment to Whitehead Light in 1875.

A child buried on Matinicus Rock in 1881, Bessie Grant, was long believed to be the daughter of Abbie and Isaac, but was in fact the daugher of Isaac's brother, John Francis Grant, and his wife, Samantha.

In 1891, Abbie Burgess wrote at Whitehead Light : Sometimes I think the time is not far distant when I shall climb these lighthouse stairs no more. It has almost seemed to me that the light was part of myself. ...Many nights I have watched the lights my part of the night, and then could not sleep the rest of the night, thinking nervously what might happen should the lights fail.

I wonder if the care of the lighthouse will follow my soul after it has left this worn out body! If I ever have a gravestone, I would like it in the form of a lighthouse or beacon.

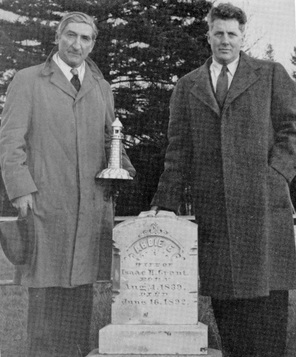

Abbie Burgess Grant died in 1892 at the age of 53. In 1945, historian Edward Rowe Snow organized a gathering at her grave in a tiny Spruce Head cemetery. A little metal lighthouse was unveiled at the foot of Abbie's grave. Abbie had her wish at last. Poet Wilbert Snow read a poem that called Abbie "the friend and guide of sailors through dark nights." The lighthouse on Abbie's grave was refurbished in 1995 by the American Lighthouse Foundation.

Samuel Burgess finally made it back to the Rock, happy to find his family alive and well. Again in 1857 he was away for three weeks during a stormy period. This time the family's food supply was reduced to one egg and a cup of corn meal mush a day before supplies arrived.

Samuel Burgess lost his job in 1861 for political reasons. Capt. John Grant, a friend of the Burgess family, became the next keeper. Abbie stayed on to help train Grant. The new keeper's son, Isaac, was the assistant keeper.

A romance quickly developed between Abbie Burgess and Isaac Grant, and they were married within a year. Abbie was officially appointed assistant keeper at $440 per year. The couple had four children at the Rock before Isaac Grant's appointment to Whitehead Light in 1875.

A child buried on Matinicus Rock in 1881, Bessie Grant, was long believed to be the daughter of Abbie and Isaac, but was in fact the daugher of Isaac's brother, John Francis Grant, and his wife, Samantha.

In 1891, Abbie Burgess wrote at Whitehead Light : Sometimes I think the time is not far distant when I shall climb these lighthouse stairs no more. It has almost seemed to me that the light was part of myself. ...Many nights I have watched the lights my part of the night, and then could not sleep the rest of the night, thinking nervously what might happen should the lights fail.

I wonder if the care of the lighthouse will follow my soul after it has left this worn out body! If I ever have a gravestone, I would like it in the form of a lighthouse or beacon.

Abbie Burgess Grant died in 1892 at the age of 53. In 1945, historian Edward Rowe Snow organized a gathering at her grave in a tiny Spruce Head cemetery. A little metal lighthouse was unveiled at the foot of Abbie's grave. Abbie had her wish at last. Poet Wilbert Snow read a poem that called Abbie "the friend and guide of sailors through dark nights." The lighthouse on Abbie's grave was refurbished in 1995 by the American Lighthouse Foundation.

The Lighthouse Board suggested in 1855 that the station should be changed to a single revolving light. Instead, possibly because of objections from mariners, a new pair of granite lighthouse towers, 180 feet apart, was built in 1857. With the lights much farther apart, the probability of them their merging into a single light when seen from the sea was lessened.

Illustration of the station circa 1870s

The lanterns held third-order Fresnel lenses; the heights of the lights above mean high water were 95 feet (north light) and 90 feet (south light). During the same year a second story was added to the keeper’s house.

Beginning in 1869, three assistant keepers were assigned to the station to tend the two lights and the fog signal. A new double dwelling for two of the assistant keepers and their families was added to the station in 1877.

A year later, the fog signal building, which had been swept away by a storm, was rebuilt. In 1888, the 1878 fog signal building was converted to an oil house, and a new brick building was erected to house the fog signal equipment and a cistern. The 1878 building was demolished by a storm in November 1888, and the surviving fog signal building was left in an exposed position, so in 1889 a 54-foot-long yellow pine bulkhead was constructed for its protection. A new brick oil house was built in the same year.

Beginning in 1869, three assistant keepers were assigned to the station to tend the two lights and the fog signal. A new double dwelling for two of the assistant keepers and their families was added to the station in 1877.

A year later, the fog signal building, which had been swept away by a storm, was rebuilt. In 1888, the 1878 fog signal building was converted to an oil house, and a new brick building was erected to house the fog signal equipment and a cistern. The 1878 building was demolished by a storm in November 1888, and the surviving fog signal building was left in an exposed position, so in 1889 a 54-foot-long yellow pine bulkhead was constructed for its protection. A new brick oil house was built in the same year.

The north light was extinguished on July 1, 1883, and the light in the south tower was changed from fixed white to fixed red. There were many complaints, and the north light was reactivated on July 1, 1888. Both lights were changed back to fixed white.

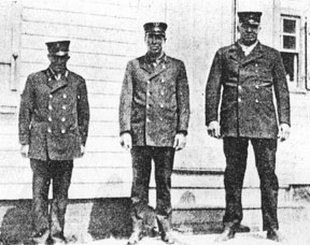

U.S. Coast Guard

Arthur J. Beal served as an assistant keeper at Matinicus Rock light from 1919 to 1929. His grandson Dave Gamage wrote the following:

When he first went there as third assistant, both lights were in operation. During his service at the Rock, one light was discontinued and the steam fog whistle was replaced by a compressed air horn. The third assistant keeper position was then eliminated. When he left the Rock my grandfather was first assistant.

My mother lived on the Rock from age four until she entered high school on the mainland. Like Abbie Burgess, my mother also raised chickens. Life on the Rock was somtimes very difficult, and there were long periods of time when one could not get on or off because of storm seas making safe landing impossible. The closest store and post office was on Matinicus Island about five miles distant, but it might just as well have been 1000 miles if one could not get there.

When he first went there as third assistant, both lights were in operation. During his service at the Rock, one light was discontinued and the steam fog whistle was replaced by a compressed air horn. The third assistant keeper position was then eliminated. When he left the Rock my grandfather was first assistant.

My mother lived on the Rock from age four until she entered high school on the mainland. Like Abbie Burgess, my mother also raised chickens. Life on the Rock was somtimes very difficult, and there were long periods of time when one could not get on or off because of storm seas making safe landing impossible. The closest store and post office was on Matinicus Island about five miles distant, but it might just as well have been 1000 miles if one could not get there.

The light station did have phone contact with Matinicus and the mainland except during extended outages when the underwater phone line was damaged. Much of their entertainment came from all the keepers' families gathering around and listening to an AM radio in the evening or playing 78 rpm records on a hand-wound Victrola. Of necessity, the younger children on the station were home schooled.

Right: This photo from about 1926 shows, left to right, Second Assistant Keeper Austin Beal, First Assistant Keeper Arthur J. Beal, and Keeper Frank O. Hilt. Keeper Hilt was described as a "300-pound genial giant." From Matinicus Isle: Its Story and its People, by Charles A. E. Long, 1926.

The north light was darkened for good on August 15, 1923. Around this time, the government decided to change all twin light stations to single lights.

Research by Terry Pepper of the Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association has revealed that the lantern from the north tower at Matinicus Rock, after some time in storage, was installed atop the 1929 lighthouse at Poe Reef, off Bois Blanc Island, Michigan.

The north light was darkened for good on August 15, 1923. Around this time, the government decided to change all twin light stations to single lights.

Research by Terry Pepper of the Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association has revealed that the lantern from the north tower at Matinicus Rock, after some time in storage, was installed atop the 1929 lighthouse at Poe Reef, off Bois Blanc Island, Michigan.

The third-order Fresnel lens that was installed in the south light in 1923 is now on display (below left) at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland.

Another storm swept Matinicus Rock in 1933, washing through the house and leaving debris waist-deep. After another storm in 1950, the Coast Guard removed most of the outbuildings. Today only one keeper's house, an 1890 oil house (an earlier oil house was swept away in an 1888 storm), and the two towers remain. The bases of the 1848 towers are still visible.

Tragedy struck on September 9, 1949, when a Coast Guard keeper, Jack Louis O'Berry, died while trying to land the dory at the rock in heavy seas. O'Berry, a native of Baltimore, Maryland, was only 19 years old.

Below is an article about Jack O'Berry by his nephew, Martin Siebert. It is reproduced in its entirety by permission; please do not share or repost.

Tragedy struck on September 9, 1949, when a Coast Guard keeper, Jack Louis O'Berry, died while trying to land the dory at the rock in heavy seas. O'Berry, a native of Baltimore, Maryland, was only 19 years old.

Below is an article about Jack O'Berry by his nephew, Martin Siebert. It is reproduced in its entirety by permission; please do not share or repost.

Gil Soucy, a Coast Guard keeper 1963-64, wrote the following in February 2012:

When I came back from Antarctica with a guaranteed assignment to Matinicus Rock, I took up residence in the newly restored stone structure. A rogue wave had broadsided the lower stick-built house and moved it several inches off its foundation. I believe this was somewhere around 1962-63. The two men in the old house made it safely to the active light and stayed there until relief crews come to assess. The house was condemned, and the first month I was on the rock a buoy tender came out and wrapped several cables around the house. They pulled it into the sea where they planned to salvage the beams and boards. No nails were used in any of the beam work and they wanted to save that, but after three days of attempting they finally had to come on the rock with chain saws and cut it up. I was about six months on the rock when they started to do work for a helicopter pad, which was finished after I got off the Rock.

When I came back from Antarctica with a guaranteed assignment to Matinicus Rock, I took up residence in the newly restored stone structure. A rogue wave had broadsided the lower stick-built house and moved it several inches off its foundation. I believe this was somewhere around 1962-63. The two men in the old house made it safely to the active light and stayed there until relief crews come to assess. The house was condemned, and the first month I was on the rock a buoy tender came out and wrapped several cables around the house. They pulled it into the sea where they planned to salvage the beams and boards. No nails were used in any of the beam work and they wanted to save that, but after three days of attempting they finally had to come on the rock with chain saws and cut it up. I was about six months on the rock when they started to do work for a helicopter pad, which was finished after I got off the Rock.

David Brackett of New Hampshire, a former Coast Guard keeper at Matinicus Rock Light, described life there to Natalie Peterson for the Granite State News. Brackett spent 14 months at "The Rock" in the 1970s while his wife lived in Camden. "Our station was immaculate. We used bowling alley wax on the hardwood floors and never wore our shoes inside," remembered Brackett.

Brackett and his three crew mates rebuilt the old tramway, used to bring supplies up to the light station. They also did a great deal of maintenance on the buildings.

Winters were rough; one storm during Brackett's tenure brought 84 mph winds and waves right over the lighthouse tower. The fog signal had an unexpected effect on Brackett. When he returned to shore, his wife wondered why he was speaking for 20 seconds at a time, then pausing. It was because he had unconsciously adjusted to the fog signal's deafening blast each 20 seconds.

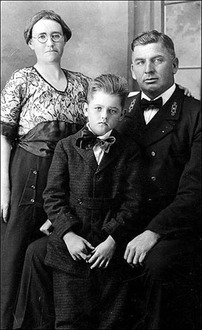

Right: Frank O. Hilt, seen here with his wife and son, was an assistant keeper at Matinicus Rock 1913-19, then principal keeper 1919-29. Courtesy of Cynthia Tupper Oakes and Karen Oakes.

Another Coast Guard crewman in the 1970s, Kevin Arsenault, later said that when he was assigned to the Rock, he was told there was “a girl behind every tree.” The only problem, of course, was that there were no trees.

Upon arriving at the station, Arsenault was informed of the resident ghost, known as Moe. The ghost, said to be the spirit of a deceased keeper, supposedly had taken up residence in the extinguished north tower, which no longer had a lantern. The word was that on some nights, a glow could be seen coming through the windows of the dark tower. Arsenault says he witnessed the glow on more than one occasion, when there was no moon and seemingly nothing inside the tower that could have produced the effect. The crewmen investigated but never found any obvious explanation for Moe.

Winters were rough; one storm during Brackett's tenure brought 84 mph winds and waves right over the lighthouse tower. The fog signal had an unexpected effect on Brackett. When he returned to shore, his wife wondered why he was speaking for 20 seconds at a time, then pausing. It was because he had unconsciously adjusted to the fog signal's deafening blast each 20 seconds.

Right: Frank O. Hilt, seen here with his wife and son, was an assistant keeper at Matinicus Rock 1913-19, then principal keeper 1919-29. Courtesy of Cynthia Tupper Oakes and Karen Oakes.

Another Coast Guard crewman in the 1970s, Kevin Arsenault, later said that when he was assigned to the Rock, he was told there was “a girl behind every tree.” The only problem, of course, was that there were no trees.

Upon arriving at the station, Arsenault was informed of the resident ghost, known as Moe. The ghost, said to be the spirit of a deceased keeper, supposedly had taken up residence in the extinguished north tower, which no longer had a lantern. The word was that on some nights, a glow could be seen coming through the windows of the dark tower. Arsenault says he witnessed the glow on more than one occasion, when there was no moon and seemingly nothing inside the tower that could have produced the effect. The crewmen investigated but never found any obvious explanation for Moe.

In 1983, the south light was automated and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern plastic lens.

U.S. Coast Guard

The Coast Guard keepers, who sometimes called Matinicus Rock "Alcatraz," were removed. A heliport had been installed on the Rock to move keepers on and off.

The remaining flashing white light is still an active aid to navigation. Under the Maine Lights Program, the lighthouse became the property of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998.

The National Audubon Society researches and protects the island's seabird population. The Rock is home to a nesting colony of puffins, as well as terns and other seabirds.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John A. Shaw (1827-1831, died in service); Phineas Spear (1831-1834, died in service); Abner Knowles (c. 1836); Thomas McKellar (c. 1838); Samuel Abbott (1839-1849); William Young (1849-1853); Samuel Burgess (1853-1861); Benjamin Burgess (assistant, 1856-1861); John H. Grant (principal keeper 1861-1867 and 1871-1890; assistant 1867-1871), Christopher Chase (1867-1871); William G. Grant, first assistant keeper, then principal keeper (1875-1900); Isaac Grant (first assistant keeper, 1861-1875); Abbie Burgess Grant (second assistant keeper, 1861-1875); John F. Grant, second assistant keeper (1876-1887); Knott C. Perry, third assistant keeper (1877-1881); Jacob T. Abbott, third assistant keeper (1881-1886); Jarvis H. Grant, second assistant keeper (1887-1888); William F. Stanley, second assistant keeper (1888-1891); Thad Wallace, third assistant keeper (1888-1891); Aldiverd Norton, third assistant keeper (1890-1897); Llewell[yn?] Norwood, third assistant keeper (1891-1895), Fred Hodgkins, third assistant keeper (1892), George A. Lewis, third assistant keeper (1892-1898); James E. Hall, third assistant keeper, later first assistant, then keeper (1896-1908); Merton Tolman, third assistant keeper, later keeper (1900-1911); Charles Burgess, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant (1897-19??); Elmer Francis Holbrook, third assistant keeper, later second assistant keeper (1898-1908); Charles Dyer, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant, then keeper (1905-1916); Harold Hutchins, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant (1909-1912); Arthur Mitchell, third assistant keeper, then second assistant, then keeper (1912-1919); George Studley, third assistant keeper (1912); J. H. Upton, second assistant keeper (1912); James Anderson (assistant, 1915-1917); Arthur J. Beal (second assistant, then first assistant 1919-1929); V. H. Fernald (c. 1923); Frank O. Hilt (assistant 1913-1919, principal keeper 1919-1929); ? Stinson (assistant, 1919-1926); Alvah Robinson (assistant c. 1930-1935, principal keeper 1935-1936); Weston Thompson (assistant, 1934-1941); R. W. Powers (c. 1933); Roscoe Fletcher (1936-1945); Edward John Schrader (Coast Guard, c. 1942); Jack O'Berry (Coast Guard, 1948-1949); Richard C. Ames (Coast Guard, early 1950s); Joseph Donahue (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Shannon Balke (Coast Guard, 1953); Tom Maddock (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Stanley Hiller (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1953-?); Richard Moore (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Robert Kinney (Coast Guard, c. 1954); Gillan Soucy (Coast Guard, August 1963- September 1964); Arthur Reker (Coast Guard, 1966-1968); Sheldon Kaminsky (Coast Guard, c. 1967-1968); Kevin J. Arsenault (Coast Guard, 1976-1977); Richard D. Seibel (1976-1977); John Burlingham (1976-1977); David Brackett (Coast Guard, c. 1970s); Thomas Nagel (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Lee Davis (Coast Guard, c. 1980s); Donald Lecours (Coast Guard, ?-1983); Larry Crete (Coast Guard, 1980-1983)

The remaining flashing white light is still an active aid to navigation. Under the Maine Lights Program, the lighthouse became the property of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998.

The National Audubon Society researches and protects the island's seabird population. The Rock is home to a nesting colony of puffins, as well as terns and other seabirds.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John A. Shaw (1827-1831, died in service); Phineas Spear (1831-1834, died in service); Abner Knowles (c. 1836); Thomas McKellar (c. 1838); Samuel Abbott (1839-1849); William Young (1849-1853); Samuel Burgess (1853-1861); Benjamin Burgess (assistant, 1856-1861); John H. Grant (principal keeper 1861-1867 and 1871-1890; assistant 1867-1871), Christopher Chase (1867-1871); William G. Grant, first assistant keeper, then principal keeper (1875-1900); Isaac Grant (first assistant keeper, 1861-1875); Abbie Burgess Grant (second assistant keeper, 1861-1875); John F. Grant, second assistant keeper (1876-1887); Knott C. Perry, third assistant keeper (1877-1881); Jacob T. Abbott, third assistant keeper (1881-1886); Jarvis H. Grant, second assistant keeper (1887-1888); William F. Stanley, second assistant keeper (1888-1891); Thad Wallace, third assistant keeper (1888-1891); Aldiverd Norton, third assistant keeper (1890-1897); Llewell[yn?] Norwood, third assistant keeper (1891-1895), Fred Hodgkins, third assistant keeper (1892), George A. Lewis, third assistant keeper (1892-1898); James E. Hall, third assistant keeper, later first assistant, then keeper (1896-1908); Merton Tolman, third assistant keeper, later keeper (1900-1911); Charles Burgess, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant (1897-19??); Elmer Francis Holbrook, third assistant keeper, later second assistant keeper (1898-1908); Charles Dyer, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant, then keeper (1905-1916); Harold Hutchins, third assistant keeper, later second assistant, then first assistant (1909-1912); Arthur Mitchell, third assistant keeper, then second assistant, then keeper (1912-1919); George Studley, third assistant keeper (1912); J. H. Upton, second assistant keeper (1912); James Anderson (assistant, 1915-1917); Arthur J. Beal (second assistant, then first assistant 1919-1929); V. H. Fernald (c. 1923); Frank O. Hilt (assistant 1913-1919, principal keeper 1919-1929); ? Stinson (assistant, 1919-1926); Alvah Robinson (assistant c. 1930-1935, principal keeper 1935-1936); Weston Thompson (assistant, 1934-1941); R. W. Powers (c. 1933); Roscoe Fletcher (1936-1945); Edward John Schrader (Coast Guard, c. 1942); Jack O'Berry (Coast Guard, 1948-1949); Richard C. Ames (Coast Guard, early 1950s); Joseph Donahue (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Shannon Balke (Coast Guard, 1953); Tom Maddock (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Stanley Hiller (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1953-?); Richard Moore (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Robert Kinney (Coast Guard, c. 1954); Gillan Soucy (Coast Guard, August 1963- September 1964); Arthur Reker (Coast Guard, 1966-1968); Sheldon Kaminsky (Coast Guard, c. 1967-1968); Kevin J. Arsenault (Coast Guard, 1976-1977); Richard D. Seibel (1976-1977); John Burlingham (1976-1977); David Brackett (Coast Guard, c. 1970s); Thomas Nagel (Coast Guard, 1979-1980); Lee Davis (Coast Guard, c. 1980s); Donald Lecours (Coast Guard, ?-1983); Larry Crete (Coast Guard, 1980-1983)