History of Monomoy Point Light, Massachusetts

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Monomoy is a peninsula extending southward from Chatham at the elbow of Cape Cod's bending arm. At times, it has been divided into two islands, North Monomoy and South Monomoy. For a thousand years or more before the arrival of Europeans, Monomoy was used by the Monomoiyicks tribe as a summer base for shellfishing and hunting.

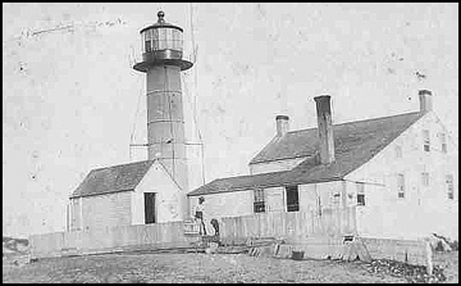

The 1849 lighthouse, c. 1859. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

The area was long a graveyard for vessels. South of Monomoy is Pollock Rip, a region of unusually strong tidal currents. A lightship was stationed at Pollock Rip for many years. It was the treacherous shoals and currents near Monomoy that caused the Pilgrims to enter Cape Cod Bay and settle at Plymouth instead of continuing south to Virginia.

A settlement grew up at Monomoy in the early 19th century, centered around the fishing industry. The community, which became known as Whitewash Village, reached its apex around 1850. As traffic in the area increased a lighthouse became a necessity.

Cape Cod's fifth lighthouse was built for $3,000 in 1823 at Monomoy Point, also called Sandy Point, eight miles from Chatham near the southern end of the peninsula. Like many early lighthouses in the area, it was a Cape Cod style light with a wooden tower and iron lantern room on the roof of a brick keeper's house. The lantern held eight lamps with 13-inch reflectors.

Engineer I.W.P. Lewis visited in 1842 and called Monomoy "one of the most important locations on the coast of the United States. Thousands of vessels pass here annually, amid the numerous and very dangerous shoals that obstruct the navigation." Keeper Solomon Doane complained that the roof leaked where it joined the tower, and that the "lantern has been so much racked by storms that it shakes so as to break the glass continually... The lantern leaks very badly in all wet weather, and is entirely out of repair." Lewis recommended that the whole establishment be rebuilt.

A settlement grew up at Monomoy in the early 19th century, centered around the fishing industry. The community, which became known as Whitewash Village, reached its apex around 1850. As traffic in the area increased a lighthouse became a necessity.

Cape Cod's fifth lighthouse was built for $3,000 in 1823 at Monomoy Point, also called Sandy Point, eight miles from Chatham near the southern end of the peninsula. Like many early lighthouses in the area, it was a Cape Cod style light with a wooden tower and iron lantern room on the roof of a brick keeper's house. The lantern held eight lamps with 13-inch reflectors.

Engineer I.W.P. Lewis visited in 1842 and called Monomoy "one of the most important locations on the coast of the United States. Thousands of vessels pass here annually, amid the numerous and very dangerous shoals that obstruct the navigation." Keeper Solomon Doane complained that the roof leaked where it joined the tower, and that the "lantern has been so much racked by storms that it shakes so as to break the glass continually... The lantern leaks very badly in all wet weather, and is entirely out of repair." Lewis recommended that the whole establishment be rebuilt.

The present cast-iron brick-lined tower was built in 1849, placing among the earliest cast-iron lighthouses in America. (Boston's Long Island Head and Vermont's Juniper Island were among the earlier ones.)

From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dorothy Bicknell

An 1850 inspection reported:

This is a new establishment altogether -- an iron light-house, a wooden dwelling, and a new fashionable apparatus. The workmanship to the light-house, I presume, is good, but it is neither large enough, nor high enough, nor stiff enough; for I can take hold with one hand of any part of the lantern and shake it to such a degree as to break the tube glasses on the lamps.

The lighthouse received a fourth-order Fresnel lens in the mid-1850s.

Monomoy was an extremely isolated station, but the keepers and families had plenty to eat, with fish, lobster, clams and waterfowl all in abundant supply.

This is a new establishment altogether -- an iron light-house, a wooden dwelling, and a new fashionable apparatus. The workmanship to the light-house, I presume, is good, but it is neither large enough, nor high enough, nor stiff enough; for I can take hold with one hand of any part of the lantern and shake it to such a degree as to break the tube glasses on the lamps.

The lighthouse received a fourth-order Fresnel lens in the mid-1850s.

Monomoy was an extremely isolated station, but the keepers and families had plenty to eat, with fish, lobster, clams and waterfowl all in abundant supply.

In later years one resourceful keeper converted his Model T Ford into an early dune buggy, making the trip by land to Chatham much faster.

An early dune buggy used by keepers to get from Monomoy to Chatham

In 1872, the Lighthouse Board recommended that Monomoy be upgraded to a second-order light, saying:

...nearly all vessels (both steamers and sailing) plying between New York and the eastern ports pass this point, and have no other guide than the lightships, which cannot be seen a sufficient distance, it is considered a matter of the greatest importance that this light should be replaced by one of sufficient power to guide vessels safely through this intricate passage...

Despite this plea, the light was not upgraded. The lighthouse was painted red in 1882, making it more visible by day. In 1892, iron trusses were added to the tower to prevent vibration.

...nearly all vessels (both steamers and sailing) plying between New York and the eastern ports pass this point, and have no other guide than the lightships, which cannot be seen a sufficient distance, it is considered a matter of the greatest importance that this light should be replaced by one of sufficient power to guide vessels safely through this intricate passage...

Despite this plea, the light was not upgraded. The lighthouse was painted red in 1882, making it more visible by day. In 1892, iron trusses were added to the tower to prevent vibration.

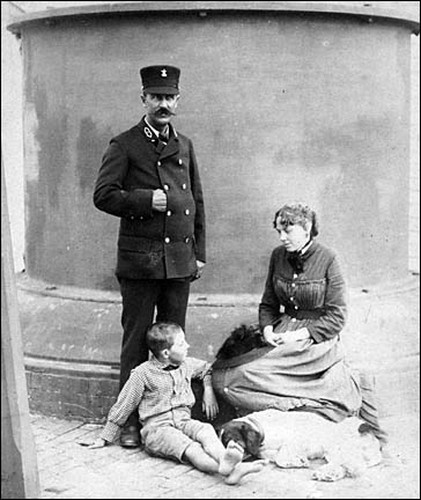

Asa L. Jones, a native of the Cape Cod town of Harwich, was keeper from 1875 to 1886. Jones, who was born in 1840, had been wounded in the Civil War. After retiring as keeper, Asa L. Jones ran an undertaking business in Harwich.

Right: Asa L. Jones, his wife Clara, and their son Maro at Monomoy Point Lighthouse. Courtesy of Emily Hills Aasted.

Asa Jones's young son, Maro Beath Jones, kept a diary that provides a glimpse of life at the light station in the 1884–86 period. Here are some excerpts, beginning when Maro was eight or nine years old:

March 25, 1884: Good weather. Papa killed a black duck.

March 31, 1884: Good weather. Papa bound a book. Seven geese came to the pond. Papa tried to shoot them.

April 6, 1884: Good weather. Papa got three shelldrakes. I scared them for Papa to shoot.

May 3, 1884: Papa went to Harwich. A lonesome day. I sent a letter to Harper’s Young People.

May 16, 1884: Very pleasant day. Papa painted his lantern.

May 29, 1884: Windy. I went with Uncle Willie to haul his nets. I went to the Station. Mama and Papa were worried about me.

June 17, 1884: Awful hot. Papa caught a rabbit.

June 22, 1884: Very good weather. THE INSPECTOR WAS HERE.

August 8, 1884: Mama and I went blackberrying.

August 10, 1884: Papa caught 81 bluefish.

June 19, 1886: The surveyors went home. Papa carried them to Chatham. The ass’t inspector came and wrote “Station in good order.”

June 28, 1886: Papa went to Harwich and he carried the first load of things from here so the people knew we were to move off. The weir men have got a live sturgeon tied and he is tame.

July 4, 1886: Not much of a Fourth of July for me. I never saw as much as an explosion with gunpowder. It is funny that today has been the most lonesome day of the summer. In the PM the drinkers of Harwich Center came after some quahogs for bait to catch black bass.

July 26, 1886: Mr. Ben Mallowes has got a sort of turtle and it looks like a sea cow. No one knows what it is, not even old whalers and Papa is going to write a man to come and get it.

July 30, 1886: Eddie Marshall came up and said the monster was dead. Thank the lord we came off for good. The wind was south west and Mama was seasick. In the bay were the largest waves I ever saw.

Maro Beath Jones also wrote an unfinished story about life at Monomoy Light Station. Emily Aasted, great granddaughter of Asa L. Jones, has graciously shared the story and you can read it below.

Asa Jones's young son, Maro Beath Jones, kept a diary that provides a glimpse of life at the light station in the 1884–86 period. Here are some excerpts, beginning when Maro was eight or nine years old:

March 25, 1884: Good weather. Papa killed a black duck.

March 31, 1884: Good weather. Papa bound a book. Seven geese came to the pond. Papa tried to shoot them.

April 6, 1884: Good weather. Papa got three shelldrakes. I scared them for Papa to shoot.

May 3, 1884: Papa went to Harwich. A lonesome day. I sent a letter to Harper’s Young People.

May 16, 1884: Very pleasant day. Papa painted his lantern.

May 29, 1884: Windy. I went with Uncle Willie to haul his nets. I went to the Station. Mama and Papa were worried about me.

June 17, 1884: Awful hot. Papa caught a rabbit.

June 22, 1884: Very good weather. THE INSPECTOR WAS HERE.

August 8, 1884: Mama and I went blackberrying.

August 10, 1884: Papa caught 81 bluefish.

June 19, 1886: The surveyors went home. Papa carried them to Chatham. The ass’t inspector came and wrote “Station in good order.”

June 28, 1886: Papa went to Harwich and he carried the first load of things from here so the people knew we were to move off. The weir men have got a live sturgeon tied and he is tame.

July 4, 1886: Not much of a Fourth of July for me. I never saw as much as an explosion with gunpowder. It is funny that today has been the most lonesome day of the summer. In the PM the drinkers of Harwich Center came after some quahogs for bait to catch black bass.

July 26, 1886: Mr. Ben Mallowes has got a sort of turtle and it looks like a sea cow. No one knows what it is, not even old whalers and Papa is going to write a man to come and get it.

July 30, 1886: Eddie Marshall came up and said the monster was dead. Thank the lord we came off for good. The wind was south west and Mama was seasick. In the bay were the largest waves I ever saw.

Maro Beath Jones also wrote an unfinished story about life at Monomoy Light Station. Emily Aasted, great granddaughter of Asa L. Jones, has graciously shared the story and you can read it below.

James P. Smith, a native of Copenhagen, became keeper in 1899. His wife died early in his stay at Monomoy, but Keeper Smith had three daughters who assisted him in his duties.

The oldest daughter, Annie, acted as housekeeper and tended the light when her father was away. In 1904 a reporter asked the Smith sisters if life at the lighthouse was lonely. Annie replied, "Oh, no! We don't have time to be lonesome. There is always something to do, with the housekeeping and the light."

Left: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey or Historic American Engineering Record, Reproduction Number MA-62-1

In February 1902, Keeper Smith and his daughters recovered the body of a Nova Scotia fisherman from the wrecked vessel Elsie M. Smith. The man's clothes had filled with sand, and Emma Smith said that he must have weighed 300 pounds. It took Keeper Smith and daughters Annie and Emma to pull the body from the surf.

With the opening of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914 and an increase in the power of Chatham Light, Monomoy Light was considered expendable. The light was discontinued in 1923. The last keeper, Douglas H. Shepherd, later wrote about his last days as keeper (thanks to Sheryl Berniche):

About February 1st 1923 I received order to extinguish this light at sunrise February 16th. The winter of this year was notorious for severe ice conditions, and on the outside beach an ice wall had formed between three and six foot high, extending the entire 12 miles to Chatham, and impossible to get down on the beach with a horse and wagon. On land across the tide water flats was a maze of ice cakes that had drifted in on every tide . . .

The morning I extinguished the light for the last time – a feeling came over both of us that is hard to explain, for we realized that this silent beacon of the night had served the mariner faithfully for 100 years, and up through this passage of time the keepers had fulfilled their golden rule of: THE LIGHT MUST SHINE . . .

The lighthouse keeper and his family is now a tradition of the past, but they leave behind them a world of their own in their devotion to duty to those afloat. The keeper took pride in his station…his wife was proud of her lighthouse home…even far removed from friend and neighbor – and except for the roar of the gale and thundering surf…they found joy and contentment in their lonely nightly vigil of:

THE LIGHT MUST SHINE.

Left: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey or Historic American Engineering Record, Reproduction Number MA-62-1

In February 1902, Keeper Smith and his daughters recovered the body of a Nova Scotia fisherman from the wrecked vessel Elsie M. Smith. The man's clothes had filled with sand, and Emma Smith said that he must have weighed 300 pounds. It took Keeper Smith and daughters Annie and Emma to pull the body from the surf.

With the opening of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914 and an increase in the power of Chatham Light, Monomoy Light was considered expendable. The light was discontinued in 1923. The last keeper, Douglas H. Shepherd, later wrote about his last days as keeper (thanks to Sheryl Berniche):

About February 1st 1923 I received order to extinguish this light at sunrise February 16th. The winter of this year was notorious for severe ice conditions, and on the outside beach an ice wall had formed between three and six foot high, extending the entire 12 miles to Chatham, and impossible to get down on the beach with a horse and wagon. On land across the tide water flats was a maze of ice cakes that had drifted in on every tide . . .

The morning I extinguished the light for the last time – a feeling came over both of us that is hard to explain, for we realized that this silent beacon of the night had served the mariner faithfully for 100 years, and up through this passage of time the keepers had fulfilled their golden rule of: THE LIGHT MUST SHINE . . .

The lighthouse keeper and his family is now a tradition of the past, but they leave behind them a world of their own in their devotion to duty to those afloat. The keeper took pride in his station…his wife was proud of her lighthouse home…even far removed from friend and neighbor – and except for the roar of the gale and thundering surf…they found joy and contentment in their lonely nightly vigil of:

THE LIGHT MUST SHINE.

After the light was discontinued, the property passed into private hands. One of the private owners was George Bearse, an auto dealer.

When he came to visit the property, Bearse was surprised to find that Navy planes had been using it for machine-gunning target practice. One bullet had come through a wall of the keeper's house and knocked out a rung on a rocking chair; another had lodged itself in a four by four beam.

Right: Historic American Engineering Record HAER MA-62, Photographer: Gerald Weinstein, July 1987.

In 1964, the Massachusetts Audubon Society restored the lighthouse and keeper's house. In 1988 Massachusetts Senator Edward M. Kennedy helped secure a federal grant for further refurbishing, a project initiated by the Lighthouse Preservation Society.

The blizzard of February 6-7, 1978, cut Monomoy into two islands, North and South Monomoy. Then, a major storm in April 2007 left the two islands connected again, with the peninsula connected to the mainland at South Beach in Chatham.

Today, Monomoy is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Monomoy is a birdwatcher's mecca, with over 300 species spotted in recent years. Gray seals breed near the southern end of Monomoy.

The Cape Cod Musuem of Natural History has offered hikes to the lighthouse and overnight stays in the past, but the programs have been discontinued. Presently, the best way to visit is via the Monomoy Island Ferry. A rather strenuous walk is necessary to reach the lighthouse, and sea conditions often make it impossible to land on the island.

A 2010 restoration of the the lighthouse and keeper's house was funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Right: Historic American Engineering Record HAER MA-62, Photographer: Gerald Weinstein, July 1987.

In 1964, the Massachusetts Audubon Society restored the lighthouse and keeper's house. In 1988 Massachusetts Senator Edward M. Kennedy helped secure a federal grant for further refurbishing, a project initiated by the Lighthouse Preservation Society.

The blizzard of February 6-7, 1978, cut Monomoy into two islands, North and South Monomoy. Then, a major storm in April 2007 left the two islands connected again, with the peninsula connected to the mainland at South Beach in Chatham.

Today, Monomoy is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Monomoy is a birdwatcher's mecca, with over 300 species spotted in recent years. Gray seals breed near the southern end of Monomoy.

The Cape Cod Musuem of Natural History has offered hikes to the lighthouse and overnight stays in the past, but the programs have been discontinued. Presently, the best way to visit is via the Monomoy Island Ferry. A rather strenuous walk is necessary to reach the lighthouse, and sea conditions often make it impossible to land on the island.

A 2010 restoration of the the lighthouse and keeper's house was funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

David Bearse (c. 1825-1841); Solomon Doane (1841-1846); Asa Nye (1846-1849 and 1853-1861); Solomon Doane (1849-1853); Nathaniel Small (1861-1865); John Tuttle (1865-1875); Asa L. Jones (1875-1886); Stephen Howe (1886-1890); Charles H. Hammond (1890-1899); James P. Smith (1899-1910); Anna Smith (1910); Edward Eveleth Brewer (1910-1911); Charles Jennings (1911-1916); Douglas H. Shepherd (1916-1923)

David Bearse (c. 1825-1841); Solomon Doane (1841-1846); Asa Nye (1846-1849 and 1853-1861); Solomon Doane (1849-1853); Nathaniel Small (1861-1865); John Tuttle (1865-1875); Asa L. Jones (1875-1886); Stephen Howe (1886-1890); Charles H. Hammond (1890-1899); James P. Smith (1899-1910); Anna Smith (1910); Edward Eveleth Brewer (1910-1911); Charles Jennings (1911-1916); Douglas H. Shepherd (1916-1923)